Sandbox:Cherry

Patient information

For the WikiDoc page for this topic, click here

|

Diarrhea |

|

Diarrhea On the Web |

|---|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Assistant Editor-in-Chief: Meagan E. Doherty

Overview

Diarrhea is loose, watery stools. A person with diarrhea typically passes stool more than three times a day. People with diarrhea may pass more than a quart of stool a day. Acute diarrhea is a common problem that usually lasts 1 or 2 days and goes away on its own without special treatment. Prolonged diarrhea persisting for more than 2 days may be a sign of a more serious problem and poses the risk of dehydration. Chronic diarrhea may be a feature of a chronic disease. Diarrhea can cause dehydration, which means the body lacks enough fluid to function properly. Dehydration is particularly dangerous in children and older people, and it must be treated promptly to avoid serious health problems. People of all ages can get diarrhea and the average adult has a bout of acute diarrhea about four times a year. In the United States, each child will have had seven to 15 episodes of diarrhea by age 5.

What are the symptoms of Diarrhea?

Diarrhea may be accompanied by cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, or an urgent need to use the bathroom. Depending on the cause, a person may have a fever or bloody stools.

What are the causes of Diarrhea?

Acute diarrhea is usually related to a bacterial, viral, or parasitic infection. Chronic diarrhea is usually related to functional disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease.

A few of the more common causes of diarrhea include the following:

- Bacterial infections. Several types of bacteria consumed through contaminated food or water can cause diarrhea. Common culprits include Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, and Escherichia coli (E. coli).

- Viral infections. Many viruses cause diarrhea, including rotavirus, Norwalk virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and viral hepatitis.

- Food intolerances. Some people are unable to digest food components such as artificial sweeteners and lactose—the sugar found in milk.

- Parasites. Parasites can enter the body through food or water and settle in the digestive system. Parasites that cause diarrhea include Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium.

- Reaction to medicines. Antibiotics, blood pressure medications, cancer drugs, and antacids containing magnesium can all cause diarrhea.

- Intestinal diseases. Inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease often lead to diarrhea.

- Functional bowel disorders. Diarrhea can be a symptom of irritable bowel syndrome.

Some people develop diarrhea after stomach surgery or removal of the gallbladder. The reason may be a change in how quickly food moves through the digestive system after stomach surgery or an increase in bile in the colon after gallbladder surgery.

People who visit foreign countries are at risk for traveler’s diarrhea, which is caused by eating food or drinking water contaminated with bacteria, viruses, or parasites. Traveler’s diarrhea can be a problem for people visiting developing countries. Visitors to the United States, Canada, most European countries, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand do not face much risk for traveler’s diarrhea.

In many cases, the cause of diarrhea cannot be found. As long as diarrhea goes away on its own, an extensive search for the cause is not usually necessary.

Who is at risk for Diarrhea?

Anyone can get diarrhea. This common problem can last a day or two or for months or years, depending on the cause. Most people get better on their own, but diarrhea can be serious for babies and older people if lost fluids are not replaced. Many people throughout the world die from diarrhea because of the large volume of water lost and the accompanying loss of salts.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests to find the cause of diarrhea may include the following:

- Medical history and physical examination. The doctor will ask you about your eating habits and medication use and will examine you for signs of illness.

- Stool culture. A sample of stool is analyzed in a laboratory to check for bacteria, parasites, or other signs of disease and infection.

- Blood tests. Blood tests can be helpful in ruling out certain diseases.

- Fasting tests. To find out if a food intolerance or allergy is causing the diarrhea, the doctor may ask you to avoid lactose, carbohydrates, wheat, or other foods to see whether the diarrhea responds to a change in diet.

- Sigmoidoscopy. For this test, the doctor uses a special instrument to look at the inside of the rectum and lower part of the colon.

- Colonoscopy. This test is similar to a sigmoidoscopy, but it allows the doctor to view the entire colon.

- Imaging tests. These tests can rule out structural abnormalities as the cause of diarrhea.

When to seek urgent medical care

Diarrhea is not usually harmful, but it can become dangerous or signal a more serious problem. You should see the doctor if you experience any of the following:

- Diarrhea for more than 3 days

- Severe pain in the abdomen or rectum

- A fever of 102 degrees or higher

- Blood in your stool or black, tarry stools

- Signs of dehydration

Treatment options

In most cases of diarrhea, replacing lost fluid to prevent dehydration is the only treatment necessary. Medicines that stop diarrhea may be helpful, but they are not recommended for people whose diarrhea is caused by a bacterial infection or parasite. If you stop the diarrhea before having purged the bacteria or parasite, you will trap the organism in the intestines and prolong the problem. Rather, doctors usually prescribe antibiotics as a first-line treatment. Viral infections are either treated with medication or left to run their course, depending on the severity and type of virus.

Tips About Food

Until diarrhea subsides, try to avoid caffeine, milk products, and foods that are greasy, high in fiber, or very sweet. These foods tend to aggravate diarrhea.

As you improve, you can add soft, bland foods to your diet, including bananas, plain rice, boiled potatoes, toast, crackers, cooked carrots, and baked chicken without the skin or fat. For children, the pediatrician may also recommend a bland diet. Once the diarrhea has stopped, the pediatrician will likely encourage children to return to a normal and healthy diet if it can be tolerated.

Contraindicated medications

Patients diagnosed with Diarrhea should avoid using the following medications:

- Ethacrynic acid

If you have been diagnosed with Diarrhea, consult your physician before starting or stopping any of these medications.

Where to find medical care for Diarrhea

Directions to Hospitals Treating Diarrhea

Prevention of Diarrhea

- Wash your hands often, especially after going to the bathroom and before eating.

- Teach children to not put objects in their mouth.

- When taking antibiotics, try eating food with Lactobacillus acidophilus, a healthy bacteria. This helps replenish the good bacteria that antibiotics can kill. Yogurt with active or live cultures is a good source of this healthy bacteria.

- Use alcohol-based hand gel frequently.

Traveler’s diarrhea happens when you consume food or water contaminated with bacteria, viruses, or parasites. You can take the following precautions to prevent traveler’s diarrhea when you travel outside of the United States:

- Do not drink tap water or use it to brush your teeth.

- Do not drink unpasteurized milk or dairy products.

- Do not use ice made from tap water.

- Avoid all raw fruits and vegetables, including lettuce and fruit salads, unless they can be peeled and you peel them yourself.

- Do not eat raw or rare meat and fish.

- Do not eat meat or shellfish that is not hot when served.

- Do not eat food from street vendors.

You can safely drink bottled water—if you are the one to break the seal—along with carbonated soft drinks, and hot drinks such as coffee or tea.

Depending on where you are going and how long you will stay, your doctor may recommend that you take antibiotics before leaving to protect you from possible infection.

What to expect (Outlook/Prognosis)

The Prognosis for diarrhea is usually good. Diarrhea is common and usually goes away on its own unless it is an underlying symptom of a chronic disease. It is important to replace lost fluid due to diarrhea because if you become severely dehydrated it can be fatal.

Sources

http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/diarrhea/

Classification

Pathophysiology Diarrhea

Normal fluid intake for an adult is about 2 L/d. The average amount of gastrointestinal secretions (composed of salivary glands, gastric, biliary, and pancreatic secretions) is 7-8 L/d, depending on the weight and age. The absorptive surface of the small intestine is formed by villis that reabsorb the majority of secreted water and electrolytes. The small intestine absorbs 75% of upper GI tract secretions. The rest of the secretions absorb in the large intestine. Colon absorbs 90% of its exposed volume, means that colon is the most effective absorbing organ in the GI system.

Decrease in the small intestine absorption, regardless of causes, may not cause diarrhea unless, there is a dysfunction in colon or the volume of the secretions exceeds the absorptive ability of the colon.

Causes

| Acute diarrhea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infectious | Non-Infectious | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacterial | Viral | Fungal | Protozoa | Medications | Poisoning | Systemic illness | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| •Shigella species ( S.dysentriae, S.flexneri, S.sonneii, S.boydii) •E.coli species (Enterotoxigenic E.coli, Enterohemorrhagic E.coli, Enteroinvasive E.coli, EPEC, EAEC) | •Astro virus •Calcivirus | •Cryptococcus •Candida albicans | •Giardia lamblia •Microsporidia | •Digoxin •Cephalosporins | •Organophosphate Poisoning •Opium withdrawal | •Hyperthyroidism •Irritable bowel syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acute diarrhea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watery | Inflammatory | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| •Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis •Cytomegalovirus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretory | Osmotic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| •Cholera •Enterotoxigenic strains of E. coli | •Lactase deficiency •Lactulose | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overview

The principal cause of diarrhea stems from ingestion of unsafe drinking water (typically from admixture of raw sewage to water supplies); the occurrence is predominantly in lesser developed countries. The common causes of acute diarrhea are infection, allergy, food intolerance, foodborne illness and/or extreme excesses of vitamin C and/or magnesium and may be accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Infectious diarrhea is most commonly caused by viral infections or bacterial toxins. Diarrhea can also be a principal symptom of more serious diseases, such as dysentery, Montezuma's Revenge, cholera, or botulism, and can also be indicative of a chronic syndrome such as Crohn's disease. Temporary diarrhea can also result from the ingestion of laxative medications or large quantities of certain foods like prunes with laxative properties. Though appendicitis patients do not generally have diarrhea, it is a common symptom of a ruptured appendix. It is also an effect of severe radiation sickness.

Causes

Life Threatening Causes

Life-threatening causes include conditions which may result in death or permanent disability within 24 hours if left untreated.

Common Causes

Causes According to Pathophysiology

Osmotic Diarrhea

Secretory Diarrhea

Motility Related Diarrhea

Causes According to Duration

Acute Diarrhea

|

Chronic Diarrhea

Causes by Organ System

Causes in Alphabetical Order

References

D/Ds

Differential Diagnosis of Diarrhea of other diseases

To review the differential diagnosis of diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of traveler's diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute watery diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute bloody diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute fatty diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic bloody diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic fatty diarrhea, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea and fever, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea and fever, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea and abdominal pain, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea and weight loss, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea and weight loss, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss, click here.

To review the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss, click here.

Diarrhea

The following table outlines the major differential diagnoses of diarrhea.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Abbreviations: GI: Gastrointestinal, CBC: Complete blood count, WBC: White blood cell, RBC: Red blood cell, Plt: Platelet, Hgb: Hemoglobin, ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C–reactive protein, IgE: Immunoglobulin E, IgA: Immunoglobulin A, ETEC: Escherichia coli enteritis, EPEC: Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, EIEC: Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, EHEC: Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, EAEC: Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli, Nl: Normal, ASCA: Anti saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies, ANCA: Anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid, CFTR: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, SLC10A2: Solute carrier family 10 member 2, SeHCAT: Selenium homocholic acid taurine or tauroselcholic acid, IEL: Intraepithelial lymphocytes, MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, ANA: Antinuclear antibodies, AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody, LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase, CPK: Creatine phosphokinase, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, ELISA: Enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay, LT: Heat–labile enterotoxin, ST: Heat–stable enterotoxin, RT-PCR: Reverse–transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, CD4: Cluster of differentiation 4, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, RUQ: Right-upper quadrant, VIP: Vasoactive intestinal peptide, GI: Gastrointestinal, FAP: Familial adenomatous polyposis, HNPCC: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, MTP: Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, Scl‑70: Anti–topoisomerase I, TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone, T4: Thyroxine, T3: Triiodothyronine, DTR: Deep tendon reflex, RNA: Ribonucleic acid

| Categories | Cause | Clinical manifestation | Lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | GI signs | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | Crohn's disease | – | + | + | + | + | ± | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

|

| ||

| Ulcerative colitis | – | + | + | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

| |||||

| Celiac disease | – | + | ± | – | ± | – | + | + |

|

– | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| |||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Cystic fibrosis | – | + | – | – | + | ± | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Chronic pancreatitis | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|||||||

| Bile acid malabsorption | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Microscopic colitis | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Infective colitis | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | + | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |||||||

| Ischemic colitis | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

| ||||

| Lactose intolerance | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | – | + | ± | – | ± | – | ± | – | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||||

| Infection | Bacterial | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Whipple's disease | – | + | + | – | + | ± | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

↓ | ↓ | ↓/↑ |

|

| ||||||

| Tropical sprue | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

|

+ | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

| ||||||

| Small bowel bacterial overgrowth | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Pseudomembranous enterocolitis | + | – | + | ± | – | + | + | ± | + | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↓ |

|

|

| |||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Campylobacteriosis | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | Nl | ||||||

| Salmonellosis | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | ↑ | ||||||||

| Shigellosis | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑/↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

|

||||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Escherichia coli enteritis | ETEC | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – |

|

+ | – | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – | – |

|

|||

| EPEC | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – | – |

| ||||

| EIEC | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – | – | |||||

| EHEC | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↓ | |||||||

| EAEC | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↓ | – |

|

|||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – | ||||||

| Vibrio cholera | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl |

|

|||||||

| Aeromonas | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

| ||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Plesiomonas | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

|||||

| Mycobacterium avium complex | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | Nl | – | ↓ | ↓ | Nl |

|

|||||||

| Food poisoning | + | – | + | ± | – | + | + | ± | + | ± | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

||||||

| Virus | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Norovirus | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | Nl |

|

↓ | Nl | Nl | – |

| ||||||

| Rotavirus | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – |

|

+ | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

| ||||||

| Echovirus | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl | – |

| ||||||

| Adenovirus | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl | – |

| ||||||

| CMV colitis | + | + | – | + | – | ± | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↓ | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||||

| HIV | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | Nl | – | ↓ | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Parasite | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Entamoeba histolytica | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | Nl | – | ↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

| |||||

| Giardia | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl | – |

| ||||||

| Cryptosporidium | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Microsporidia | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Isospora | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Tumors | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Carcinoid tumor | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| VIPoma | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | + |

|

– | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| ||||

| Zollinger–Ellison syndrome | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Somatostatinoma | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Lymphoma | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Colorectal cancer | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

|

– | + | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| |||||

| Medication/Toxicity | Medications | + | + | + | – | ± | ± | + | + | – | – | – | ↑/↓ | – | ↑ | Nl | Nl |

|

– |

| ||||

| Factitious diarrhea | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↑/↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

| |||||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Heavy metal ingestion | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Organophosphate poisoning | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

|

| ||||

| Opium withdrawal | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – |

|

– | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

| ||||||

| Iatrogenic | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Short bowel syndrome | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

|

| ||||

| Radiation enteritis | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Dumping syndrome | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + |

|

– | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||||

| Others | Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||||

| Abetalipoproteinemia | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||||

| Hyperthyroidism | – | + | + | – | – | ± | + | + | – | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

|||||

| Diabetic neuropathy | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||||

| Systemic sclerosis | – | + | + | ± | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||||

References

- ↑ Casburn-Jones, Anna C; Farthing, Michael Jg (2004). "Traveler's diarrhea". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 19 (6): 610–618. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03287.x. ISSN 0815-9319.

- ↑ Kamat, Deepak; Mathur, Ambika (2006). "Prevention and Management of Travelers' Diarrhea". Disease-a-Month. 52 (7): 289–302. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2006.08.003. ISSN 0011-5029.

- ↑ Pfeiffer, Margaret L.; DuPont, Herbert L.; Ochoa, Theresa J. (2012). "The patient presenting with acute dysentery – A systematic review". Journal of Infection. 64 (4): 374–386. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2012.01.006. ISSN 0163-4453.

- ↑ Barr W, Smith A (2014). "Acute diarrhea". Am Fam Physician. 89 (3): 180–9. PMID 24506120.

- ↑ Amil Dias J (2017). "Celiac Disease: What Do We Know in 2017?". GE Port J Gastroenterol. 24 (6): 275–278. doi:10.1159/000479881. PMID 29255768.

- ↑ Kotloff KL, Riddle MS, Platts-Mills JA, Pavlinac P, Zaidi A (2017). "Shigellosis". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33296-8. PMID 29254859. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Yamamoto-Furusho, J.K.; Bosques-Padilla, F.; de-Paula, J.; Galiano, M.T.; Ibañez, P.; Juliao, F.; Kotze, P.G.; Rocha, J.L.; Steinwurz, F.; Veitia, G.; Zaltman, C. (2017). "Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal: Primer Consenso Latinoamericano de la Pan American Crohn's and Colitis Organisation". Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 82 (1): 46–84. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2016.07.003. ISSN 0375-0906.

- ↑ Borbély, Yves M; Osterwalder, Alice; Kröll, Dino; Nett, Philipp C; Inglin, Roman A (2017). "Diarrhea after bariatric procedures: Diagnosis and therapy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (26): 4689. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4689. ISSN 1007-9327.

- ↑ Crawford, Sue E.; Ramani, Sasirekha; Tate, Jacqueline E.; Parashar, Umesh D.; Svensson, Lennart; Hagbom, Marie; Franco, Manuel A.; Greenberg, Harry B.; O'Ryan, Miguel; Kang, Gagandeep; Desselberger, Ulrich; Estes, Mary K. (2017). "Rotavirus infection". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 3: 17083. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.83. ISSN 2056-676X.

- ↑ Kist M (2000). "[Chronic diarrhea: value of microbiology in diagnosis]". Praxis (Bern 1994) (in German). 89 (39): 1559–65. PMID 11068510.

- ↑ Guerrant RL, Shields DS, Thorson SM, Schorling JB, Gröschel DH (1985). "Evaluation and diagnosis of acute infectious diarrhea". Am. J. Med. 78 (6B): 91–8. PMID 4014291.

- ↑ López-Vélez R, Turrientes MC, Garrón C, Montilla P, Navajas R, Fenoy S, del Aguila C (1999). "Microsporidiosis in travelers with diarrhea from the tropics". J Travel Med. 6 (4): 223–7. PMID 10575169.

- ↑ Wahnschaffe, Ulrich; Ignatius, Ralf; Loddenkemper, Christoph; Liesenfeld, Oliver; Muehlen, Marion; Jelinek, Thomas; Burchard, Gerd Dieter; Weinke, Thomas; Harms, Gundel; Stein, Harald; Zeitz, Martin; Ullrich, Reiner; Schneider, Thomas (2009). "Diagnostic value of endoscopy for the diagnosis of giardiasis and other intestinal diseases in patients with persistent diarrhea from tropical or subtropical areas". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 42 (3): 391–396. doi:10.1080/00365520600881193. ISSN 0036-5521.

- ↑ Mena Bares LM, Carmona Asenjo E, García Sánchez MV, Moreno Ortega E, Maza Muret FR, Guiote Moreno MV, Santos Bueno AM, Iglesias Flores E, Benítez Cantero JM, Vallejo Casas JA (2017). "75SeHCAT scan in bile acid malabsorption in chronic diarrhoea". Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 36 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.remn.2016.08.005. PMID 27765536.

- ↑ Gibson RJ, Stringer AM (2009). "Chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea". Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 3 (1): 31–5. doi:10.1097/SPC.0b013e32832531bb. PMID 19365159.

- ↑ Abraham BP, Sellin JH (2012). "Drug-induced, factitious, & idiopathic diarrhoea". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 26 (5): 633–48. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2012.11.007. PMID 23384808.

- ↑ Reintam Blaser A, Deane AM, Fruhwald S (2015). "Diarrhoea in the critically ill". Curr Opin Crit Care. 21 (2): 142–53. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000188. PMID 25692805.

- ↑ McMahan ZH, DuPont HL (2007). "Review article: the history of acute infectious diarrhoea management--from poorly focused empiricism to fluid therapy and modern pharmacotherapy". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (7): 759–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03261.x. PMID 17373914.

- ↑ Schiller LR (2012). "Definitions, pathophysiology, and evaluation of chronic diarrhoea". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 26 (5): 551–62. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2012.11.011. PMID 23384801.

- ↑ Giannella RA (1986). "Chronic diarrhea in travelers: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations". Rev. Infect. Dis. 8 Suppl 2: S223–6. PMID 3523719.

- ↑ Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR; et al. (2005). "Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology". Can J Gastroenterol. 19 Suppl A: 5A–36A. PMID 16151544.

- ↑ Sauter GH, Moussavian AC, Meyer G, Steitz HO, Parhofer KG, Jüngst D (2002). "Bowel habits and bile acid malabsorption in the months after cholecystectomy". Am J Gastroenterol. 97 (7): 1732–5. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05779.x. PMID 12135027.

- ↑ Maiuri L, Raia V, Potter J, Swallow D, Ho MW, Fiocca R; et al. (1991). "Mosaic pattern of lactase expression by villous enterocytes in human adult-type hypolactasia". Gastroenterology. 100 (2): 359–69. PMID 1702075.

- ↑ RUBIN CE, BRANDBORG LL, PHELPS PC, TAYLOR HC (1960). "Studies of celiac disease. I. The apparent identical and specific nature of the duodenal and proximal jejunal lesion in celiac disease and idiopathic sprue". Gastroenterology. 38: 28–49. PMID 14439871.

- ↑ Konvolinka CW (1994). "Acute diverticulitis under age forty". Am J Surg. 167 (6): 562–5. PMID 8209928.

- ↑ Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF (2006). "The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications". Gut. 55 (6): 749–53. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909. PMC 1856208. PMID 16698746.

- ↑ Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA (2003). "Amebiasis". N Engl J Med. 348 (16): 1565–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMra022710. PMID 12700377.

- ↑ Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA (1996). "Colonic adaptation to daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance". Am J Clin Nutr. 64 (2): 232–6. PMID 8694025.

- ↑ Briet F, Pochart P, Marteau P, Flourie B, Arrigoni E, Rambaud JC (1997). "Improved clinical tolerance to chronic lactose ingestion in subjects with lactose intolerance: a placebo effect?". Gut. 41 (5): 632–5. PMC 1891556. PMID 9414969.

- ↑ BLACK-SCHAFFER B (1949). "The tinctoral demonstration of a glycoprotein in Whipple's disease". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 72 (1): 225–7. PMID 15391722.

Risk factors

Risk Factors

- Antibiotic use

- High-risk sexual behavior (STDs)

- Immunosuppression

- Recent travel to endemic area

Pathophysiology prev

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5szNmKtyBW4%7C350}} |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Sandbox:Cherry On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sandbox:Cherry |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Risk Factors

- Antibiotic use

- High-risk sexual behavior (STDs)

- Immunosuppression

- Recent travel to endemic area

Pathophysiology prev

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5szNmKtyBW4%7C350}} |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Sandbox:Cherry On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sandbox:Cherry |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [3] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Risk Factors

- Antibiotic use

- High-risk sexual behavior (STDs)

- Immunosuppression

- Recent travel to endemic area

History and Symptoms

- History should include:

- Appearance of bowel movements

- Travel history

- Associated symptoms

- Immune status

- Woodland exposure

Lab findings

Overview

Laboratory Findings

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Glucose

- White blood cells (WBC)

- Urinalysis

- Calcium

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) / creatinine

- Hepatitis serologies

- Stool examinations:

- Stool cultures

- Stool electrolytes

- Stool osmolality

- Ova and parasites

- Fecal lactoferrin

- Fecal leukocytes

- Test for C. difficile

Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests

Spot Stool Analysis

Because a 72-hour stool collection is cumbersome, qualitative tests continue to be used in the clinic.

Occult Blood

- A positive test result suggests the presence of inflammatory bowel disease, neoplastic diseases or celiac sprue and other sprue like syndromes.[1]

- Fecal occult blood positivity can also be associated with laxative-induced diarrhea, pancreatic maldigestion, idiopathic secretory diarrhea, and microscopic colitis.[2]

White Blood Cells

- The standard method of detecting white blood cells (WBCs) in stool is with Wright's staining and microscopy.

- Latex agglutination test is highly sensitive and specific for the detection of neutrophils (lactoferrin) in stool in acute infectious diarrhea and in pseudomembranous colits.[3]

- Calprotectin is a zinc and calcium binding protein that is derived mostly from neutrophils and monocytes and fecal calprotectin may be useful for distinguishing inflammatory from noninflammatory causes of chronic diarrhea.[4]

Sudan Stain for Fat

- Excess stool fat should be evaluated by means of a Sudan stain or by direct measurement.[5]

- The presence of excess fat globules by stain or stool fat excretion >14 g/24 h suggests malabsorption or maldigestion.

- Stool fat concentration of >8% strongly suggests pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

Fecal Cultures

- In immunocompetent patients, bacterial infections are rarely the cause of chronic diarrhea and routine fecal cultures usually are not usually obtained. However, under specific environmental conditions suspecting Aeromonas or Pleisiomonas species, at least one fecal culture should be performed in the evaluation of these patients.[6] The epidemiological clues raising suspicion for the presence of these organisms include consumption of untreated well water and swimming in fresh water ponds and streams.

- In immunocompromised patients, bacterial cultures ought to be part of the initial diagnostic evaluation, as common infectious causes of acute diarrhea, such as Campylobacter or Salmonella, can cause persistent diarrhea.

- Infections with yeast and fungi have been reported as causes of both nosocomial and community-acquired chronic diarrhea, even in immunocompetent individuals.[7] Protozoa and parasites causes are now analyzed by fecal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and chronic viral infections are diagnosed from gastrointestinal mucosal biopsy specimens rather than stool samples.[8]

Quantitative Stool Analysis

A 48- or 72-hour quantitative stool collection is useful in the work-up of chronic diarrhea. Full analysis of the collection includes measurement of weight, fat content, osmolality, electrolyte concentrations, magnesium concentration and output, pH, occult blood, and based upon the history fecal chymotrypsin or elastase activity and laxatives. Several days before and during the collection period, the patient should eat a regular diet of moderately high fat content or a fixed diet for some patients to ensure that adequate amounts of fat and calories are consumed. During the collection period, no diagnostic tests should be done that would disturb the normal eating pattern, aggravate diarrhea, diminish diarrhea, add foreign material to the gut, or risk an episode of incontinence. All but essential medications should be avoided, and any antidiarrheal medication begun before the collection period should be held.

Fecal Weight

- Knowledge of stool weight is of direct help in diagnosis and management in some instances. Stool weights greater than 500 g/day are rarely if ever seen in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and stool weights less than 1000 g/day are evidence against pancreatic syndrome.

- Low stool weight in a patient complaining of “severe diarrhea” suggests that incontinence or pain may be the dominant problem.

- Response to fasting such as complete cessation of diarrhea during fasting is strong evidence that the mechanism of diarrhea involves something ingested (nonabsorbable substance or nutrient causing osmotic diarrhea, or unabsorbed fatty acids or laxatives causing secretory diarrhea).[9]

Stool Osmotic Gap

- The osmotic gap is calculated from electrolyte concentrations in stool water by the following formula : 290 - 2([Na+] + [K+]).

- The osmolality of stool within the distal intestine should be used for this calculation rather than the osmolality measured in fecal fluid, because measured fecal osmolality begins to increase in the collection container almost immediately when carbohydrates are converted by bacterial fermentation to osmotically active organic acids.

- Osmotic diarrheas, where electrolytes account for most of stool osmolality, are characterized by osmotic gaps >125 mOsm/kg, whereas secretory diarrheas where nonelectrolytes account for most of the osmolality of stool water, typically have osmotic gaps <50 mOsm/kg. In mixed cases, such in modest carbohydrate malabsorption (in which most of the carbohydrate load is converted to organic anions that obligate the fecal excretion of cations including Na+ and K+), the osmotic gap may lie between 50 and 125.[10]

Fecal pH

- A fecal pH of < 5.3 indicates that carbohydrate malabsorption (such as that associated with lactulose or sorbitol ingestion) is a major cause of diarrhea.

- A pH of > 5.6 argues against carbohydrate malabsorption as the only cause and malabsorption syndrome that involves fecal loss of amino acids and fatty acids in addition to carbohydrate, have a higher fecal pH.[10]

Fecal Fat Concentration and Output

- The upper limit of fecal fat output measured in normal subjects (without diarrhea) ingesting normal amounts of dietary fat is approximately 7 g/day (9% of dietary fat intake)and values more than this signify the presence of steatorrhea.

- A fecal fat concentration of <9.5 g/100 g of stool more likely to be seen in small intestinal malabsorptive syndromes because of the diluting effects of coexisting fluid malabsorption.[11]

- A fecal fat concentrations of ≥9.5 g/100 g of stool were seen in pancreatic and biliary steatorrhea, in which fluid absorption in the small bowel is intact.[12]

Analysis for Laxatives

Analysis for laxatives should be done early in the evaluation of diarrhea of unknown etiology. The simplest test for a laxative is alkalinization of 3 mL of stool supernatant or urine with one drop of concentrated sodium hydroxide and a pink or red color is a positive result. Stool water can be analyzed specifically for phenolphthalein, emetine and bisacodyl and its metabolites, using chromatographic or chemical tests. Urine can be analyzed for anthraquinone derivatives.

- If stool electrolyte analysis suggests secretory diarrhea (osmotic gap <50), the patient may have ingested a laxative capable of causing secretory diarrhea, such as sodium sulfate or sodium phosphate ingestion.[13]

- If stool electrolyte analysis suggests osmotic diarrhea (osmotic gap >125 mOsm/kg), magnesium (Mg2+) laxatives may have been ingested.[14]

- If fecal osmolality is significantly less than 290 mOsm/kg (the osmolality of plasma), water or hypotonic urine has been added to the stool.

- If the osmolality is far above that of plasma, hypertonic urine may have been added to stool. Urinary contamination can be confirmed by a finding of high monovalent cation concentration (e.g., [Na+] + [K+] > 165, physiologically impossible in stool water) and a high concentration of urea or creatinine in stool water.

Endoscopic Examination and Mucosal Biopsy

Sigmoidoscopy and Colonoscopy

- A strong history and complete examination determine which scopes to be used and chronic conditions like melanosis coli, ulceration, polyps, tumors, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and amebiasis can be diagnosed by inspection of the colonic mucosa.

- Diseases such as microscopic colitis (lymphocytic and collagenous colitis), amyloidosis, Whipple's disease, granulomatous infections, and schistosomiasis, where the mucosa appears normal need mucosal biopsy and can be diagnosed histologically.

Upper Tract Endoscopy

- The presence of steatorrhea makes a small intestinal malabsorptive disorder to be the likely etiology and an endoscope that allows specimens to be obtained from the proximal and distal duodenum and/or proximal jejunum would be the best investigation of choice.

- Crohn's disease, giardiasis, celiac sprue, intestinal lymphoma, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, hypogammaglobulinemic sprue, Whipple's disease, lymphangiectasia, abetalipoproteinemia, amyloidosis, mastocytosis, and various mycobacterial, fungal, protozoal, and parasitic infections can be diagnosed through upper GI scopy and biopsy.

- An aspirate of small intestinal contents can be sent for quantitative aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture if bacterial overgrowth is suspected and for microscopic examination for parasites.

Radiography

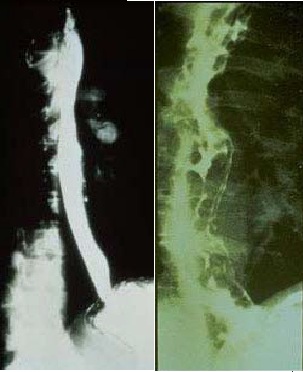

- Radiographic studies of the stomach and colon may be complementary to endoscopy and colonoscopy because barium-contrast radiograms can better detect fistulas and strictures.

- An unsuspected diagnosis is made by small intestinal radiography. Abnormal findings such as excess luminal fluid, dilation, and an irregular mucosal surface may lead to a suspicion of celiac sprue, Whipple's disease, or intestinal lymphoma which would help in further investigations and making the ultimate diagnosis. Other diseases that might be diagnosed with small intestinal radiography are carcinoid tumors and scleroderma.

- Computed tomography is performed in patients with chronic diarrhea to examine for pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic infections such as tuberculosis, intestinal lymphoma, carcinoid syndrome, and other neuroendocrine tumors.

- Mesenteric or celiac angiography may show evidence of intestinal ischemia caused by atherosclerosis or vasculitis that are rare causes of chronic diarrhea.

Tests for Bacterial Overgrowth

- The gold standard for diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth has been quantitative culture of an aspirate of luminal fluid and specifically a positive jejunal culture (>106 organisms/mL) in chronic diarrhea patients can be considered evidence of clinically significant bacterial overgrowth in the upper small intestine.[15]

- A breath test using [14C] glycocholate is used to test bacterial overgrowth. The radiolabeled conjugated bile acid is deconjugated by the bacteria, and the 14C in the side chain is metabolized to 14CO2, which is exhaled.

- Another 14C-breath test using [14C] xylose, nonradioactive glucose and nonradioactive lactulose have been developed to test bacterial overgrowth.[16]

- An elevated concentration of hydrogen in breath after overnight fasting also has been proposed as an insensitive but specific marker of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. This elevated hydrogen concentration may also be seen in patients with malabsorption syndrome.

- An abnormal Schilling II test result (radiolabeled B12 given with intrinsic factor) that normalizes after therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics has also been considered as a test for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (the so-called Schilling III test).[17]

References

- ↑ Viana Freitas BR, Kibune Nagasako C, Pavan CR, Silva Lorena SL, Guerrazzi F, Saddy Rodrigues Coy C; et al. (2013). "Immunochemical fecal occult blood test for detection of advanced colonic adenomas and colorectal cancer: comparison with colonoscopy results". Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013: 384561. doi:10.1155/2013/384561. PMC 3844264. PMID 24319453.

- ↑ Fine KD (1996). "The prevalence of occult gastrointestinal bleeding in celiac sprue". N Engl J Med. 334 (18): 1163–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199605023341804. PMID 8602182.

- ↑ Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, Rufo PA, Zholudev A, Boone J, Lyerly D; et al. (2003). "Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation". Am J Gastroenterol. 98 (6): 1309–14. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07458.x. PMID 12818275.

- ↑ van Rheenen PF, Van de Vijver E, Fidler V (2010). "Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis". BMJ. 341: c3369. doi:10.1136/bmj.c3369. PMC 2904879. PMID 20634346. Review in: Ann Intern Med. 2011 Jan 18;154(2):JC1-12

- ↑ Fine KD, Ogunji F (2000). "A new method of quantitative fecal fat microscopy and its correlation with chemically measured fecal fat output". Am J Clin Pathol. 113 (4): 528–34. doi:10.1309/0T2W-NN7F-7T8Q-5N8C. PMID 10761454.

- ↑ Rautelin H, Hänninen ML, Sivonen A, Turunen U, Valtonen V (1995). "Chronic diarrhea due to a single strain of Aeromonas caviae". Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 14 (1): 51–3. PMID 7537217.

- ↑ Friedman M, Ramsay DB, Borum ML (2007). "An unusual case report of small bowel Candida overgrowth as a cause of diarrhea and review of the literature". Dig Dis Sci. 52 (3): 679–80. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9604-4. PMID 17277989.

- ↑ Koontz F, Weinstock JV (1996). "The approach to stool examination for parasites". Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 25 (3): 435–49. PMID 8863034.

- ↑ Fordtran JS (1967). "Speculations on the pathogenesis of diarrhea". Fed Proc. 26 (5): 1405–14. PMID 6051321.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Eherer AJ, Fordtran JS (1992). "Fecal osmotic gap and pH in experimental diarrhea of various causes". Gastroenterology. 103 (2): 545–51. PMID 1634072.

- ↑ Bo-Linn GW, Fordtran JS (1984). "Fecal fat concentration in patients with steatorrhea". Gastroenterology. 87 (2): 319–22. PMID 6735076.

- ↑ Hammer HF (2010). "Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: diagnostic evaluation and replacement therapy with pancreatic enzymes". Dig Dis. 28 (2): 339–43. doi:10.1159/000319411. PMID 20814209.

- ↑ Carlson J, Fernlund P, Ivarsson SA, Jakobsson I, Neiderud J, Nilsson KO; et al. (1994). "Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an unexpected cause of severe chronic diarrhoea in a child". Acta Paediatr. 83 (1): 119–21. PMID 8193462.

- ↑ Fine KD, Santa Ana CA, Fordtran JS (1991). "Diagnosis of magnesium-induced diarrhea". N Engl J Med. 324 (15): 1012–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199104113241502. PMID 2005938.

- ↑ Saad RJ, Chey WD (2013). "Breath Testing for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Maximizing Test Accuracy". Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.055. PMID 24095975.

- ↑ Corazza GR, Menozzi MG, Strocchi A, Rasciti L, Vaira D, Lecchini R; et al. (1990). "The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Reliability of jejunal culture and inadequacy of breath hydrogen testing". Gastroenterology. 98 (2): 302–9. PMID 2295385.

- ↑ "Schilling test of vitamin B12 absorption". Br Med J. 1 (5639): 300–1. 1969. PMC 1982167. PMID 5762651.

Other Imaging Findings

Other diagnostic studies

Other Diagnostic Studies

- Breath hydrogen test

- HIV testing for those patients suspected of having HIV

Medical therapy

Overview

Medical Therapy

- Fluid resuscitation (oral, if not IV)

- Patients should be advised to do the following until symptoms subside:

- For patients with lactose intolerance, a lactose-free diet is advised

- For patients with malabsorption diseases, a gluten free diet is advised

- Consultation with oncology, surgery and/or gastroenterology may be required for intestinal neoplasm

- Control blood sugar (diabetic neuropathy)

Empirical Therapy

Empirical therapy is used as an initial treatment before diagnostic testing or after diagnostic testing has failed to confirm a diagnosis or when there is no specific treatment or when specific treatment fails to effect a cure.

- Empirical trials of antimicrobial therapy like metronidazole for protozoal diarrhea or fluoroquinolone for enteric bacterial diarrhea if the prevalence of bacterial or protozoal infection is high in a specific community or situation.

- Most cases of diarrhea, except for high-volume secretory states, respond to a sufficiently high dose of opium or morphine. Codeine, synthetic opioids diphenoxylate and loperamide are less potent. However loperamide is generally used because of its less abuse potential.

- The somatostatin analogue octreotide has proven effectiveness in carcinoid tumors and other peptide-secreting tumors, dumping syndrome, and chemotherapy-induced diarrhea.

- Intraluminal agents include adsorbants, such as activated charcoal, and binding resins like bismuth and stool modifiers, such as medicinal fiber.

Pharmacotherapy

- Antibiotics (malabsorption diseases)

- Anticholinergics (IBS)

- Antimolality agents

- Antibiotic therapy (severe disease)

- Metoclopramide (diabetic neuropathy)

- Nonspecific antidiarrheal agents

Symptomatic Treatment

- Symptomatic treatment for diarrhea involves the patient consuming adequate amounts of water to replace that loss, preferably mixed with electrolytes to provide essential salts and some amount of nutrients. For many people, further treatment is unnecessary.

- The following types of diarrhea indicate medical supervision is required:

- Diarrhea in infants;

- Moderate or severe diarrhea in young children;

- Diarrhea associated with blood;

- Diarrhea that continues for more than two weeks;

- Diarrhea that is associated with more general illness such as non-cramping abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, etc;

- Diarrhea in travelers, since they are more likely to have exotic infections such as parasites;

- Diarrhea in food handlers, because of the potential to infect others;

- Diarrhea in institutions such as hospitals, child care centers, or geriatric and convalescent homes.

A severity score is used to aid diagnosis.[1]

Pathogen Specific

Immunocompetent

- Bacterial [2]

- 1. Shigella species

- Preferred regimen (1):

- Adult dose: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively bid for 3 days (if susceptible ) OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, OR 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- Pediatric dose: TMP-SMZ, 5 and 25 mg/kg, respectively bid for 3 days

- Preferred regimen (2):

- Adult dose: Nalidixic acid 1 g/d for 5 days OR Ceftriaxone; Azithromycin

- Pediatric dose: Nalidixic acid, 55 mg/kg/d for 5 days

- 2. Non-typhi species of Salmonella

- Preferred regimen: Not recommended routinely, but if severe or patient is younger than 6 monthes or older than 50 year old or has prostheses, valvular heart disease, severe atherosclerosis, malignancy, or uremia, TMP-SMZ (if susceptible) OR Fluoroquinolone, bid for 5 to 7 days; Ceftriaxone, 100 mg/kg/d in 1 or 2 divided doses

- 3. Campylobacter species

- Preferred regimen: Erythromycin 500 mg bid for 5 days

- 4. Escherichia coli species

- 4.1. Enterotoxigenic

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid, for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 4.2. Enteropathogenic

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid, for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 4.3. Enteroinvasive

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid, for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 4.4. Enterohemorrhagic

- Preferred regimen: Avoid antimotility drugs; role of antibiotics unclear, and administration should be avoided.

- 5. Aeromonas/Plesiomonas

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 3 days (if susceptible), Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 6. Yersinia species

- Preferred regimen: Antibiotics are not usually required; Deferoxamine therapy should be withheld; for severe infections or associated bacteremia treat as for immunocompromised hosts, using combination therapy with Doxycycline, Aminoglycoside, TMP-SMZ, OR Fluoroquinolone

- 7. Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139

- Preferred regimen (1): Doxycycline 300-mg single dose

- Preferred regimen (2): Tetracycline 500 mg qid for 3 days

- Preferred regimen (3): TMP-SMZ 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 3 days

- Preferred regimen (4): single-dose Fluoroquinolone

- 8. Toxigenic Clostridium difficile

- Preferred regimen: Offending antibiotic should be withdrawn if possible; Metronidazole, 250 mg qid to 500 mg tid for 3 to 10 days

- Parasites [2]

- 1. Giardia

- Preferred regimen: Metronidazole 250-750 mg tid for 7-10 days

- 2. Cryptosporidium species

- Preferred regimen: If severe, consider Paromomycin, 500 mg tid for 7 days

- 3. Isospora species

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 7 to 10 days

- 4. Cyclospora species

- Preferred regimen: TMP/SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 7 days

- 5. Microsporidium species

- Preferred regimen: Not determined

- 6. Entamoeba histolytica

- Preferred regimen (1): Metronidazole 750 mg tid for 5 to 10 days AND Diiodohydroxyquin 650 mg tid for 20 days

- Preferred regimen (2): Metronidazole 750 mg tid for 5 to 10 days AND Paromomycin 500 mg tid for 7 days

Immunocompromised

- Bacterial [2]

- 1. Shigella species:

- Preferred regimen (1):

- Adult dose: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively bid for 7 to 10 days (if susceptible ) OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, OR 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 7 to 10 days)

- Pediatric dose:TMP-SMZ, 5 and 25 mg/kg, respectively bid for 7 to 10 days

- Preferred regimen (2):

- Adult dose: Nalidixic acid 1 g/d for 7 to 10 days OR Ceftriaxone; Azithromycin

- Pediatric dose: Nalidixic acid, 55 mg/kg/d for 7 to 10 days

- 2. Non-typhi species of Salmonella

- Preferred regimen: Not recommended routinely, but if severe or patient is younger than 6 monthes or older than 50 old or has prostheses, valvular heart disease, severe atherosclerosis, malignancy, or uremia, TMP-SMZ (if susceptible) OR Fluoroquinolone, bid for 14 days (or longer if relapsing); ceftriaxone, 100 mg/kg/d in 1 or 2 divided doses

- 3. Campylobacter species

- Preferred regimen: Erythromycin, 500 mg bid for 5 days (may require prolonged treatment)

- 4. Escherichia coli species

- 4.1. Enterotoxigenic

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days) (Consider fluoroquinolone as for enterotoxigenic E. coli)

- 4.2. Enteropathogenic

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid,for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 4.3. Enteroinvasive

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid,for 3 days (if susceptible), OR Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg Ofloxacin, 400 mg Norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 4.4. Enterohemorrhagic

- Preferred regimen: Avoid antimotility drugs; role of antibiotics unclear, and administration should be avoided.

- 5. Aeromonas/Plesiomonas

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 3 days (if susceptible), Fluoroquinolone (e.g., 300 mg ofloxacin, 400 mg norfloxacin, or 500 mg Ciprofloxacin bid for 3 days)

- 6. Yersinia species

- Preferred regimen: Doxycycline, Aminoglycoside (in combination) or TMP-SMZ or Fluoroquinolone

- 7. Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139

- Preferred regimen: Doxycycline, 300-mg single dose; or Tetracycline, 500 mg qid for 3 days; or TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, bid for 3 days; or single-dose Fluoroquinolone

- 8. Toxigenic Clostridium difficile

- Preferred regimen: Offending antibiotic should be withdrawn if possible; Metronidazole, 250 mg qid to 500 mg tid for 3 to 10 days

- Parasites [2]

- 1. Giardia

- Preferred regimen: Metronidazole, 250-750 mg tid for 7-10 days

- 2. Cryptosporidium species

- Preferred regimen: Paromomycin, 500 mg tid for 14 to 28 days, then bid if needed; highly active antiretroviral therapy including a protease inhibitor is warranted for patients with AIDS

- 3. Isospora species

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMZ, 160 and 800 mg, respectively, qid for 10 days, followed by TMP-SMZ thrice weekly, or weekly Sulfadoxine (500 mg) and Pyrimethamine (25 mg) indefinitely for patients with AIDS

- 4. Cyclospora species

- 5. Microsporidium species

- Preferred regimen: Albendazole, 400 mg bid for 3 weeks; highly active antiretroviral therapy including a protease inhibitor is warranted for patients with AIDS

- 6. Entamoeba histolytica

- Preferred regimen: Metronidazole, 750 mg tid for 5 to 10 days, plus either Diiodohydroxyquin, 650 mg tid for 20 days, or Paromomycin, 500 mg tid for 7 days

Contraindicated medications

Diarrhea is considered an absolute contraindication to the use of the following medications:

References

- ↑ Ruuska T, Vesikari T (1990). "Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes". Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 22 (3): 259–67. PMID 2371542.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV; et al. (2001). "Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea". Clin Infect Dis. 32 (3): 331–51. doi:10.1086/318514. PMID 11170940.

Pathophysiology prev

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5szNmKtyBW4%7C350}} |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Sandbox:Cherry On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sandbox:Cherry |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [4] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Video codes

Normal video

{{#ev:youtube|x6e9Pk6inYI}} {{#ev:youtube|4uSSvD1BAHg}} {{#ev:youtube|PQXb5D-5UZw}} {{#ev:youtube|UVJYQlUm2A8}}

Video in table

Floating video

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypYI_lmLD7g%7C350}} |

Redirect

- REDIRECTEsophageal web

synonym website

https://mq.b2i.sg/snow-owl/#!terminology/snomed/10743008

Image

Image to the right

|

Image and text to the right

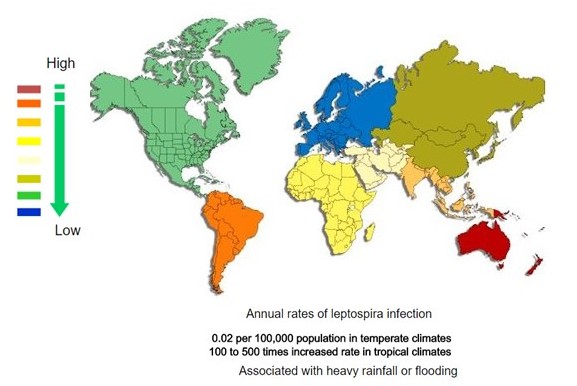

<figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline> </figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

</figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

Gallery

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Libre Pathology. http://librepathology.org/wiki/index.php/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas

REFERENCES

- CS1 errors: Vancouver style

- CS1 maint: Unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: PMC format

- Pages with reference errors

- Patient information

- Primary care

- Gastroenterology

- Water-borne diseases

- Digestive disease symptoms

- Conditions diagnosed by stool test

- Pages using columns-list with unknown parameters

- Needs overview

- Hepatology

- Disease

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/2/2f/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_2.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/a/a3/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histopathology_3.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/d/d5/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_4.JPG)