Heroin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Extremely High |

| Routes of administration | Inhalation, Transmucosal, Intravenous, Oral, Intranasal, Rectal, Intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | <35% (oral), 44–61% (inhaled)[1] |

| Protein binding | 0% (morphine metabolite 35%) |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3–5 min (IV, inhaled)[2] |

| Excretion | 90% renal as glucuronides, rest biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

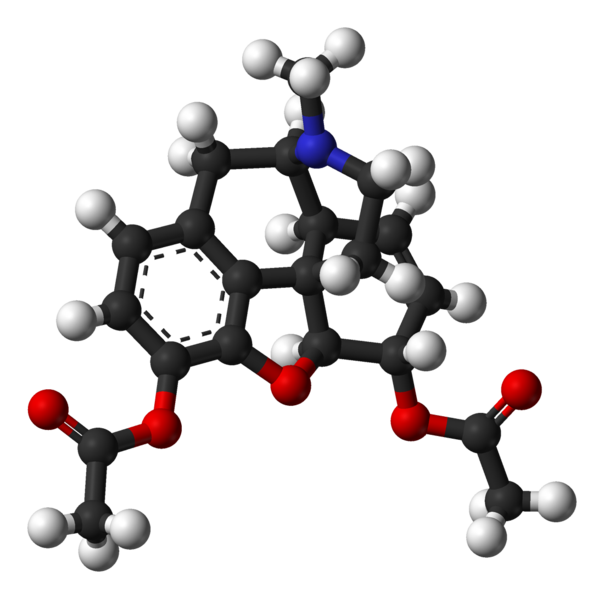

| Formula | C21H23NO5 |

| Molar mass | 369.41 |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Heroin |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Heroin at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Heroin at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Heroin

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Heroin Risk calculators and risk factors for Heroin

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [3]

Street Names/Slangs: Aunt Hazel, birdie powder, Black, Black Eagle, Black Pearl, Black Stuff, Black Tar, Boy, Brown, Brown Crystal, Brown Rhine, Brown Sugar Junk, Brown Tape, Chiba or Chiva, China White, dog food, Dope White, Dr. Feelgood, Dragon, H, He, hong-yen, Junk, lemonade, Mexican Brown, Mexican Horse, Mexican Mud, Mexican mud, Mud, Number 4, Number 8, old Steve, pangonadalot, Sack, Skag, Skunk Number 3, Smac, Snow, Snowball Scat, Tar, White Boy, White Girl, White Horse, White Lady, White Nurse, White Stuff, witch hazel

Overview

Heroin (INN: diacetylmorphine, BAN: diamorphine) is a semi-synthetic opioid synthesized from morphine, a derivative of the opium poppy. It is the 3, 6-diacetyl ester of morphine (hence diacetylmorphine). The white crystalline form is commonly the hydrochloride salt diacetylmorphine hydrochloride.

As with other opiates, heroin is used both as a pain-killer and a recreational drug.

One of the most common methods of heroin use is via intravenous injection. When taken orally, heroin undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism via deacetylation, making it a prodrug for the systemic delivery of morphine.[1] When the drug is injected, however, it avoids this first-pass effect, very rapidly crossing the blood-brain barrier due to the presence of the acetyl groups, which render it much more lipid-soluble than morphine itself.[2] Once in the brain, it is deacetylated into 3- and 6-monoacetylmorphine and morphine, which bind to μ-opioid receptors resulting in intense euphoria with the feeling centered in the gut.

Frequent administration has a high potential for causing addiction and may quickly lead to tolerance. If a continual, sustained use of heroin for as little as three days is stopped abruptly, withdrawal symptoms can appear. This is much shorter than the withdrawal effects experienced from other common painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone.[3][4]

Internationally, heroin is controlled under Schedules I and IV of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[5] It is illegal to manufacture, possess, or sell heroin in the United States and the UK. However, under the name diamorphine, heroin is a legal prescription drug in the United Kingdom. Popular street names for heroin include black tar, smack, junk, skag, horse, brain, chaw, chiva, and others. These are specific references to heroin and not used to describe any other drug. Dope could be used to refer to heroin, but may also indicate other drugs, from laudanum a century ago to nearly any contemporary recreational drug.

History

The opium poppy was cultivated in lower Mesopotamia as long ago as 3400 BC.[6] The chemical analysis of opium in the 19th century revealed that most of its activity could be ascribed to two ingredients, codeine and morphine.

Heroin was first processed in 1874 by C.R. Alder Wright, an English chemist working at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School in London, England. He had been experimenting with combining morphine with various acids. He boiled anhydrous morphine alkaloid with acetic anhydride over a stove for several hours and produced a more potent, acetylated form of morphine, now called diacetylmorphine. The compound was sent to F.M. Pierce of Owens College in Manchester for analysis, who reported the following to Wright:

- Doses ... were subcutaneously injected into young dogs and rabbits ... with the following general results ... great prostration, fear, and sleepiness speedily following the administration, the eyes being sensitive, and pupils constrict, considerable salivation being produced in dogs, and slight tendency to vomiting in some cases, but no actual emesis. Respiration was at first quickened, but subsequently reduced, and the heart's action was diminished, and rendered irregular. Marked want of coordinating power over the muscular movements, and loss of power in the pelvis and hind limbs, together with a diminution of temperature in the rectum of about 4° (rectal failure).[7]

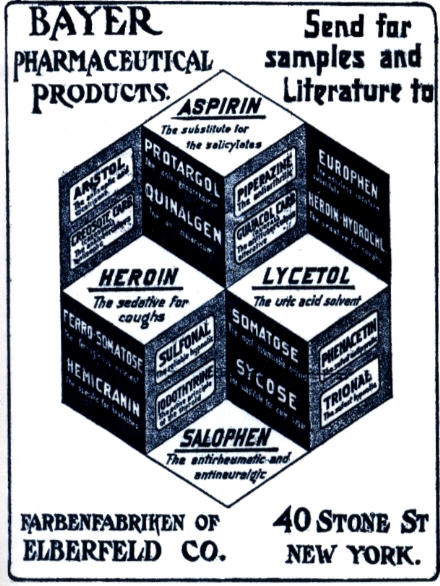

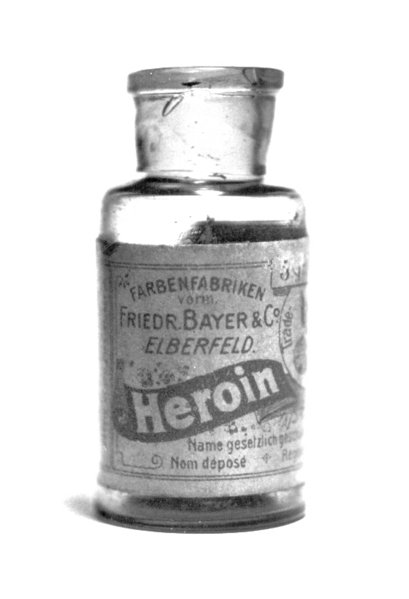

Wright's invention, however, did not lead to any further developments, and heroin only became popular after it was independently re-synthesized 23 years later by another chemist, Felix Hoffmann. Hoffmann, working at the Bayer pharmaceutical company in Elberfeld, Germany, was instructed by his supervisor Heinrich Dreser to acetylate morphine with the objective of producing codeine, a natural derivative of the opium poppy, similar to morphine but less potent and less addictive. But instead of producing codeine, the experiment produced an acetylated form of morphine that was actually 1.5-2 times more potent than morphine itself. Bayer would name the substance "heroin", probably from the word heroisch, German for heroic, because in field studies people using the medicine felt "heroic".[8]

From 1898 through to 1910 heroin was marketed as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough medicine for children. Bayer marketed heroin as a cure for morphine addiction before it was discovered that heroin is converted to morphine when metabolized in the liver, and as such, "heroin" was basically only a quicker acting form of morphine. The company was somewhat embarrassed by this new finding and it became a historical blunder for Bayer.[9]

As with aspirin, Bayer lost some of its trademark rights to heroin following the German defeat in World War I.[10]

In the United States the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was passed in 1914 to control the sale and distribution of heroin. The law did allow heroin to be prescribed and sold for medical purposes. In particular, recreational users could often still be legally supplied with heroin and use it. In 1924, the United States Congress passed additional legislation banning the sale, importation or manufacture of heroin in the United States. It is now a Schedule I substance, and is thus illegal in the United States.

Usage and effects

Indicated for:

Recreational uses: Other uses:

|

Contraindications:

|

Side effects

Skin:

|

Heroin is used as a recreational drug for the intense euphoria it induces, which diminishes with increased tolerance. Its popularity with recreational drug users, compared to morphine and other opiates, stems from its perceived different effects;[12] this is unsupported by clinical research.

Controlled studies comparing the physiological and subjective effects of injected heroin and morphine in post-addicts, subjects showed no preference for either drug when administered on a single-injection basis. Equipotent, injected doses had comparable action courses, with no difference in their ability to induce euphoria, ambition, nervousness, relaxation, drowsiness, or sleepiness.[13] Data acquired from short-term addiction studies did not indicate that heroin tolerance develops more rapidly than morphine. The findings have been discussed in relation to the physicochemical properties of heroin and morphine and the metabolism of heroin. When compared to other opioids — hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and meperidine, post-addicts showed a strong preference for heroin and morphine, suggesting that heroin and morphine lend themselves to abuse and addiction. Morphine and heroin were also much more likely to produce euphoria, and other subjective effects when compared to most opioid analgesics.[14][15] Heroin can be administered several ways, including snorting and injection, and may be smoked by inhaling its vapors when heated, i.e. "chasing the dragon".

Some users mix heroin with cocaine in a "speedball" or "snowball" that usually is injected intravenously, smoked, or dissolved in water and then snorted, producing a more intense rush than heroin alone, but is more dangerous because the combination of the short-acting stimulant with the longer-acting depressant increases the risk of seizure, or overdose with one or both drugs.

Once in the brain, heroin is rapidly metabolized to morphine by removal of the acetyl groups and is thus a prodrug. Morphine is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier as quickly as heroin, which gives heroin a subjectively stronger 'high'. In either case, a morphine molecule binds with opioid receptors, inducing the subjective, opioid high.

The onset of heroin's effects depends upon the method of administration; orally, heroin is completely metabolized in vivo to morphine before crossing the blood-brain barrier; the effects are the same as with oral morphine. Snorting results in an onset within 3 to 5 minutes; smoking results in an almost immediate, 7 to 11 seconds, milder effect that strengthens; intravenous injection induces a rush and euphoria usually taking effect within 30 seconds; intramuscular and subcutaneous injection take effect within 3 to 5 minutes.

Heroin metabolizes into morphine, a μ-opioid (mu-opioid) agonist. It acts on endogenous μ-opioid receptors that are spread in discrete packets throughout the brain, spinal cord and gut in almost all mammals. Heroin, along with other opioids, are agonists to four endogenous neurotransmitters. They are β-endorphin, dynorphin, leu-enkephalin, and met-enkephalin. The body responds to heroin in the brain by reducing (and sometimes stopping) production of the endogenous opioids when heroin is present. Endorphins are regularly released in the brain and nerves, attenuating pain. Their other functions are still obscure, but are probably related to the effects produced by heroin besides analgesia (antitussin, anti-diarrheal). The reduced endorphin production in heroin users creates a dependence on the heroin, and the cessation of heroin results in extremely uncomfortable symptoms including pain (even in the absence of physical trauma). This set of symptoms is called withdrawal syndrome. It has an onset 6 to 8 hours after the last dose of heroin.

The heroin dose used for recreational purposes depends strongly on the level of addiction. A first-time user tyically uses between 5 and 20 mg of heroin, but a typical heavy addict would use between 300 and 500 mg per day.[16]

Large doses of heroin can be fatal. The drug can be used for suicide or as a murder weapon. The serial killer Dr Harold Shipman used it on his victims as did Dr John Bodkin Adams (see his victim, Edith Alice Morrell). It can sometimes be difficult to determine whether a heroin death was an accident, suicide or murder as with the deaths of Sid Vicious, Joseph Krecker, Janis Joplin, Tim Buckley, Jim Morrison, Layne Staley, Kurt Cobain, and Bradley Nowell have been attributed to heroin overdose.[17]

Regulation

In the United States, heroin is a schedule I drug according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 making it illegal to possess without a DEA license. Possession of more than 100 grams of heroin or a mixture containing heroin is punishable with a minimum mandatory sentence of 5 years of imprisonment in a federal prison.

In Canada heroin is a controlled substance under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Every person who seeks or obtains heroin without disclosing authorization 30 days prior to obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offense and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years. Possession for purpose of trafficking is guilty of an indictable offense and liable to imprisonment for life.

In Hong Kong, heroin is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. It can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies heroin without prescription can be fined $10,000 (HKD). The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing heroin is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of heroin for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years of jail time.

In the United Kingdom, heroin is available by prescription, though it is a restricted Class A drug. According to the British National Formulary (BNF) edition 50, diamorphine hydrochloride may be used in the treatment of acute pain, myocardial infarction, acute pulmonary oedema, and chronic pain. The treatment of chronic non-malignant pain must be supervised by a specialist. The BNF notes that all opioid analgesics cause dependence and tolerance but that this is "no deterrent in the control of pain in terminal illness". When used in the palliative care of cancer patients, heroin is often injected using a syringe driver.

Production and trafficking: The Golden Triangle

Manufacturing

Heroin is produced for the black market through opium refinement process - first, morphine is isolated from opium. This crude morphine is then acetylated by heating with acetic anhydride. Purification of the obtained crude heroin as a hydrochloride salt provides a water-soluble salt form of white or yellowish powder.

Crude opium is carefully dissolved in hot water but the resulting hot soup is not boiled. Mechanical impurities - twigs - are scooped together with the foam. The mixture is then made alkaline by gradual addition of lime. Lime causes a number of unwelcome components present in opium to precipitate out of the solution. (The impurities include the useless alkaloids, resins, proteins). The precipitate is removed by filtration through a cloth, washed with additional water and discarded. The filtrates containing water-soluble calcium salt of morphine are then acidified by careful addition of ammonium chloride. This causes the morphine to precipitate. The morphine precipitate is collected by filtration and dried before the next step. The crude morphine (which makes only about 10% of the weight of the used opium) is then heated together with acetic anhydride at 85 °C (185 °F) for six hours. The reaction mixture is then cooled, diluted with water, alkalized with sodium carbonate and the precipitated crude heroin is filtered and washed with water. This crude water-insoluble free-base product (which by itself is usable, for smoking) is further purified and decolourised by dissolution in hot alcohol, filtration with activated charcoal and concentration of the filtrates. The concentrated solution is then acidified with hydrochloric acid, diluted with ether and the precipitated white hydrochloride salt of heroin is collected by filtration. This precipitate is the so-called "no. 4 heroin", the standard product exported to the Western markets. (Side-product residues from purification or the crude free base product are also available on the markets, as the "tar heroin" - a cheap substitute of inferior quality.)

The initial stage of opium refining - the isolation of morphine - is relatively easy to perform in rudimentary settings - even by substituting suitable fertilizers for pure chemical reagents. However, the later steps (acetylation, purification, precipitation as hydrochloride) are more involved - they use large quantities of dangerous chemicals and solvents and they require both skill and patience. The final step is particularly tricky as the highly flammable ether can easily ignite during the positive-pressure filtration (the explosion of vapor-air mixture can obliterate the refinery). If the heroin does ignite, the result is a catastrophic explosion.

History of heroin traffic

The origins of the present international illegal heroin trade can be traced back to laws passed in many countries in the early 1900s that closely regulated the production and sale of opium and its derivatives including heroin. At first, heroin flowed from countries where it was still legal into countries where it was no longer legal. By the mid-1920s, heroin production had been made illegal in many parts of the world. An illegal trade developed at that time between heroin labs in China (mostly in Shanghai and Tianjin) and other nations. The weakness of government in China and conditions of civil war enabled heroin production to take root there. Chinese triad gangs eventually came to play a major role in the heroin trade.

Heroin trafficking was virtually eliminated in the U.S. during World War II due to temporary trade disruptions caused by the war. Japan's war with China had cut the normal distribution routes for heroin and the war had generally disrupted the movement of opium. After the second world war, the Mafia took advantage of the weakness of the postwar Italian government and set up heroin labs in Sicily. The Mafia took advantage of Sicily's location along the historic route opium took from Iran westward into Europe and the United States. Large scale international heroin production effectively ended in China with the victory of the communists in the civil war in the late 1940s. The elimination of Chinese production happened at the same time that Sicily's role in the trade developed.

Although it remained legal in some countries until after World War II, health risks, addiction, and widespread abuse led most western countries to declare heroin a controlled substance by the latter half of the 20th century.

Between the end of World War II and the 1970s, much of the opium consumed in the west was grown in Iran, but in the late 1960s, under pressure from the U.S. and the United Nations, Iran engaged in anti-opium policies. While opium production never ended in Iran, the decline in production in those countries led to the development of a major new cultivation base in the so-called "Golden Triangle" region in South East Asia. In 1970-71, high-grade heroin laboratories opened in the Golden Triangle. This changed the dynamics of the heroin trade by expanding and decentralizing the trade. Opium production also increased in Afghanistan due to the efforts of Turkey and Iran to reduce production in their respective countries. Lebanon, a traditional opium supplier, also increased its role in the trade during years of civil war.

Soviet-Afghan war led to increased production in the Pakistani-Afghani border regions. It increased international production of heroin at lower prices in the 1980s. The trade shifted away from Sicily in the late 1970s as various criminal organizations violently fought with each other over the trade. The fighting also led to a stepped up government law enforcement presence in Sicily. All of this combined to greatly diminish the role of the country in the international heroin trade.

Trafficking

- See also: Opium production

Traffic is heavy worldwide, with the biggest producer being Afghanistan.[18] According to U.N. sponsored survey,[19] as of 2004, Afghanistan accounted for production of 87 percent of the world's heroin.[20] Opium production in that country has increased rapidly since, reaching an all-time high in 2006. War once again appeared as a facilitator of the trade.[21]

At present, opium poppies are mostly grown in Afghanistan, and in Southeast Asia, especially in the region known as the Golden Triangle straddling Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Yunnan province in the People's Republic of China. There is also cultivation of opium poppies in the Sinaloa region of Mexico and in Colombia. The majority of the heroin consumed in the United States comes from Mexico and Colombia. Up until 2004, Pakistan was considered one of the biggest opium-growing countries. However, the efforts of Pakistan's Anti-Narcotics Force have since reduced the opium growing area by 59% as of 2001.

Conviction for trafficking in heroin carries the death penalty in most South-east Asia and some East Asia and Middle Eastern countries (see Use of death penalty worldwide for details), among which Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand are the most strict. The penalty applies even to citizens of countries where the penalty is not in place, sometimes causing controversy when foreign visitors are arrested for trafficking, for example the arrest of nine Australians in Bali or the hanging of Australian citizen Van Tuong Nguyen in Singapore, both in 2005.

Sandra Gregory has written an autobiography covering her experience of getting caught with Heroin at a Thai airport.

Risks of non-medical use

- For intravenous users of heroin (and any other substance), the use of non-sterile needles and syringes and other related equipment leads to several serious risks:

- the risk of contracting blood-borne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis

- the risk of contracting bacterial or fungal endocarditis and possibly venous sclerosis

- abscesses caused by transfer of fungus from the skin of lemons, the acidic juice of which can be added to impure heroin to increase its solubility

- Poisoning from contaminants added to "cut" or dilute heroin

- Chronic constipation

- Addiction and an increasing tolerance.

- Physical dependence can result from prolonged use of all opiate and opioids, resulting in withdrawal symptoms on cessation of use.

- Decreased kidney function. (although it is not currently known if this is due to adulterants used in the cut)[22][23][24][25][26]

Many countries and local governments have begun funding programs that supply sterile needles to people who inject illegal drugs in an attempt to reduce these contingent risks and especially the contraction and spread of blood-borne diseases. The Drug Policy Alliance reports that up to 75% of new AIDS cases among women and children are directly or indirectly a consequence of drug use by injection. But despite the immediate public health benefit of needle exchanges, some see such programs as tacit acceptance of illicit drug use. The United States federal government does not operate needle exchanges, although some state and local governments do support needle exchange programs.

A heroin overdose is usually treated with an opioid antagonist, such as naloxone (Narcan), or naltrexone, which has a high affinity for opioid receptors but does not activate them. This blocks heroin and other opioid antagonists and causes an immediate return of consciousness and the beginning of withdrawal symptoms when administered intravenously. The half-life of this antagonist is usually much shorter than that of the opiate drugs it is used to block, so the antagonist usually has to be re-administered multiple times until the opiate has been metabolized by the body.

Depending on drug interactions and numerous other factors, death from overdose can take anywhere from several minutes to several hours due to anoxia because the breathing reflex is suppressed by µ-opioids. An overdose is immediately reversible with an opioid antagonist injection. Heroin overdoses can occur due to an unexpected increase in the dose or purity or due to diminished opiate tolerance. However, most fatalities reported as overdoses are probably caused by interactions with other depressant drugs like alcohol or benzodiazepines.[27] It should also be noted that, since heroin can cause nausea and vomiting, a significant number of deaths attributed to heroin overdose are caused by aspiration of vomitus by an unconscious victim.

The LD50 for a physically addicted person is prohibitively high, to the point that there is no general medical consensus on where to place it. Several studies done in the 1920s gave users doses of 1,600–1,800 mg of heroin in one sitting, and no adverse effects were reported. Even for a non-user, the LD50 can be placed above 350 mg though some sources give a figure of between 75 and 375 mg for a 75 kg person.[28]

Street heroin is of widely varying and unpredictable purity. This means that the user may prepare what they consider to be a moderate dose while actually taking far more than intended. Also, those who use the drug after a period of abstinence have tolerances below what they were during active addiction. If a dose comparable to their previous use is taken, an effect greater to what the user intended is caused, in extreme cases an overdose could result.

It has been speculated that an unknown portion of heroin related deaths are the result of an overdose or allergic reaction to quinine, which may sometimes be used as a cutting agent.[29]

A final source of overdose in users comes from place conditioning. Heroin use, like other drug using behaviors, is highly ritualized. While the mechanism has yet to be clearly elucidated, it has been shown that longtime heroin users, immediately before injecting in a common area for heroin use, show an acute increase in metabolism and a surge in the concentration of opiate-metabolizing enzymes. This acute increase, a reaction to a location where the user has repeatedly injected heroin, imbues him or her with a strong (but temporary) tolerance to the toxic effects of the drug. When the user injects in a different location, this environment-conditioned tolerance does not occur, giving the user a much lower-than-expected ability to metabolize the drug. The user's typical dose of the drug, in the face of decreased tolerance, becomes far too high and can be toxic, leading to overdose.[30]

A small percentage of heroin smokers may develop symptoms of toxic leukoencephalopathy. This is believed to be caused by an uncommon adulterant that is only active when heated. Symptoms include slurred speech and difficulty walking.

Harm reduction approaches to heroin

Proponents of the harm reduction philosophy seek to minimize the harms that arise from the recreational use of heroin. Safer means of taking the drug, such as smoking or nasal, oral and rectal insertion, are encouraged, due to injection having higher risks of overdose, infections and blood-borne viruses. Where the strength of the drug is unknown, users are encouraged to try a small amount first to gauge the strength, to minimize the risks of overdose. For the same reason, poly drug use (the use of two or more drugs at the same time) is discouraged. Users are also encouraged to not use heroin on their own, as others can assist in the event of an overdose. Heroin users who choose to inject should always use new needles, syringes, spoons/steri-cups and filters every time they inject and not share these with other users. Governments that support a harm reduction approach often run Needle & Syringe exchange programs, which supply new needles and syringes on a confidential basis, as well as education on proper filtering prior to injection, safer injection techniques, safe disposal of used injecting gear and other equipment used when preparing heroin for injection may also be supplied including citric acid sachets/vitamin C sachets, steri-cups, filters, alcohol pre-injection swabs, sterile water ampules and tourniquets (to stop use of shoe laces or belts).

Withdrawal

The withdrawal syndrome from heroin may begin starting from within 6 to 24 hours of discontinuation of sustained use of the drug; however, this time frame can fluctuate with the degree of tolerance as well as the amount of the last consumed dose. Symptoms may include: sweating, malaise, anxiety, depression, priapism, extra sensitivity of the genitals in females, general feeling of heaviness, cramp-like pains in the limbs, yawning, tears, sleep difficulties (insomnia), cold sweats, chills, severe muscle and bone aches not precipitated by any physical trauma; nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, goose bumps, cramps, and fever.[31][32] Many users also complain of a painful condition, the so-called "itchy blood", which often results in compulsive scratching that causes bruises and sometimes ruptures the skin, leaving scabs. Abrupt termination of heroin use causes muscle spasms in the legs and arms of the user (restless leg syndrome). Users taking the "cold turkey" approach (withdrawal without using symptom-reducing or counteractive drugs), or induced withdrawal with opiate antagonist drugs, are more likely to experience the negative effects of withdrawal in a more pronounced manner.

Two general approaches are available to ease the physical part of opioid withdrawal. The first is to substitute a longer-acting opioid such as methadone or buprenorphine for heroin or another short-acting opioid and then slowly taper the dose.

In the second approach, benzodiazepines such as diazepam (Valium) may temporarily ease the often extreme anxiety of opioid withdrawal. The most common benzodiazepine employed as part of the detox protocol in these situations is oxazepam (Serax). Benzodiazepine use must be prescribed with care because benzodiazepines have an addiction potential, and many opioid users also use other central nervous system depressants, especially alcohol. Also, though unpleasant, opioid withdrawal seldom has the potential to be fatal, whereas complications related to withdrawal from benzodiazepines, barbiturates and alcohol (such as epileptic seizures, cardiac arrest, and delirium tremens) can prove hazardous and are potentially fatal.

Many symptoms of opioid withdrawal are due to rebound hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system, which can be suppressed with clonidine (Catapres), a centrally-acting alpha-2 agonist primarily used to treat hypertension. Another drug sometimes used to relieve the "restless legs" symptom of withdrawal is baclofen, a muscle relaxant. Diarrhea can likewise be treated symptomatically with the peripherally active opioid drug loperamide.

Buprenorphine is one of the substances most recently licensed for the substitution of opioids in the treatment of users. Being a partial opioid agonist/antagonist, it develops a lower grade of tolerance than heroin or methadone due to the so-called ceiling effect. It also has less severe withdrawal symptoms than heroin when discontinued abruptly, which should never be done without proper medical supervision. It is usually administered every 24-48 hrs. Buprenorphine is a kappa-opioid receptor antagonist. This gives the drug an anti-depressant effect, increasing physical and intellectual activity. Buprenorphine also acts as a partial agonist at the same μ-receptor where opioids like heroin exhibit their action. Due to its effects on this receptor, all patients whose tolerance is above a certain level are unable to obtain any "high" from other opioids during buprenorphine treatment except for very high doses.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have been testing a sustained-release "depot" form of buprenorphine that can relieve cravings and withdrawal symptoms for up to six weeks.[33] A sustained-release formulation would allow for easier administration and adherence to treatment, and reduce the risk of diversion or misuse.

Methadone is another μ-opioid agonist most often used to substitute for heroin in treatment for heroin addiction. Compared to heroin, methadone is well (but slowly) absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and has a much longer duration of action of approximately 24 hours. Thus methadone maintenance avoids the rapid cycling between intoxication and withdrawal associated with heroin addiction. In this way, methadone has shown some success as a "less harmful substitute"; despite bearing about the same addiction potential as heroin, it is recommended for those who have repeatedly failed to complete withdrawal or have recently relapsed. As of 2005, the μ-opioid agonist buprenorphine is also being used to manage heroin addiction, being a superior, though still imperfect and not yet widely known alternative to methadone. Methadone, since it is longer-acting, produces withdrawal symptoms that appear later than with heroin, but usually last considerably longer and can in some cases be more intense. Methadone withdrawal symptoms can potentially persist for over a month, compared to heroin where significant physical symptoms would subside in 4 days.

Three opioid antagonists are known: naloxone and the longer-acting naltrexone and nalmefene. These medications block the effects of heroin, as well as the other opioids at the receptor site. Recent studies have suggested that the addition of naltrexone may improve the success rate in treatment programs when combined with the traditional therapy.

The University of Chicago undertook preliminary development of a heroin vaccine in monkeys during the 1970s, but it was abandoned. There were two main reasons for this. Firstly, when immunized monkeys had an increase in dose of x16, their antibodies became saturated and the monkey had the same effect from heroin as non-immunized monkeys. Secondly, until they reached the x16 point immunized monkeys would substitute other drugs to get a heroin-like effect. These factors suggested that immunized human users would simply either take massive quantities of heroin, or switch to other drugs.

There is also a controversial treatment for heroin addiction based on an Iboga-derived African drug, ibogaine. Many people travel abroad for ibogaine treatments that generally interrupt substance use disorders for 3-6 months or more in up to 80% of patients.[34] Relapse may occur when the person returns home to their normal environment however, where drug seeking behavior may return in response to social and environmental cues. Ibogaine treatments are carried out in several countries including Mexico and Canada as well as, in South and Central America and Europe. Opioid withdrawal therapy is the most common use of ibogaine. Some patients find ibogaine therapy more effective when it is given several times over the course of a few months or years. A synthetic derivative of ibogaine, 18-methoxycoronaridine was specifically designed to overcome cardiac and neurotoxic effects seen in some ibogaine research but, the drug has not yet found its way into clinical research..

Heroin prescription

The UK Department of Health's Rolleston Committee report in 1926 established the British approach to heroin prescription to users, which was maintained for the next forty years: dealers were prosecuted, but doctors could prescribe heroin to users when withdrawing from it would cause harm or severe distress to the patient. This "policing and prescribing" policy effectively controlled the perceived heroin problem in the UK until 1959 when the number of heroinists doubled every sixteenth month during a period of ten years, 1959-1968. [35]. The failure changed the attitudes; in 1964 only specialized clinics and selected approved doctors were allowed to prescribe heroin to users. The law was changed in 1968 in a more restrictive direction. From the 1970s, the emphasis shifted to abstinence and the prescription of methadone, until now only a small number of users in the UK are prescribed heroin.[36]

In 1994 Switzerland began a trial program featuring a heroin prescription for users not well suited for withdrawal programs—e.g. those that had failed multiple withdrawal programs. The aim is maintaining the health of the user in order to avoid medical problems stemming from low-quality street heroin. Reducing drug-related crime was another goal. Users can more easily get or maintain a paid job through the program as well. The first trial in 1994 began with 340 users and it was later expanded to 1000 after medical and social studies suggested its continuation. Participants are prescribed to inject heroin in specially designed pharmacies for about US $13 per dose.[37]

The success of the Swiss trials led German, Dutch,[38] and Canadian[39] cities to try out their own heroin prescription programs.[40] Some Australian cities (such as Sydney) have trialed legal heroin supervised injecting centers, in line with other wider harm minimization programs. Heroin is unavailable on prescription however, and remains illegal outside the injecting room, and effectively decriminalized inside the injecting room.

Drug interactions

Opioids are strong central nervous system depressants, but regular users develop physiological tolerance allowing gradually increased dosages. In combination with other central nervous system depressants, heroin may still kill even experienced users, particularly if their tolerance to the drug has reduced or the strength of their usual dose has increased.

Toxicology studies of heroin-related deaths reveal frequent involvement of other central nervous system depressants, including alcohol, benzodiazepines such as temazepam (Restoril; Normison), and, to a rising degree, methadone. Ironically, benzodiazepines are often used in the treatment of heroin addiction while they cause much more severe withdrawal symptoms.

Cocaine sometimes proves to be fatal when used in combination with heroin. Though "speedballs" (when injected) or "moonrocks" (when smoked) are a popular mix of the two drugs among users, combinations of stimulants and depressants can have unpredictable and sometimes fatal results. In the United States in early 2006, a rash of deaths was attributed to either a combination of fentanyl and heroin, or pure fentanyl masquerading as heroin particularly in the Detroit Metro Area; one news report refers to the combination as 'laced heroin', though this is likely a generic rather than a specific term.[41]

See also

| File:Wiktionary-logo-en-v2.svg | Look up heroin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Morphine

- Opioids

- Black Tar Heroin

- Cheese (recreational drug)

- China White

- HIV in Yunnan

- Drugs and prostitution

- Ibogaine

- Monoacetylmorphine

- Dipropanoylmorphine

- Diacetyldihydromorphine

- Recreational drug use

- Psychoactive drug

- The Great Binge

- Opium

- Polish heroin

- Poppy

- Drug injection

- Illegal drug trade

- Illicit drug use in Australia

- Entomotoxicology

- Trainspotting

References

- ↑ Sawynok J. "The therapeutic use of heroin: a review of the pharmacological literature." Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1986 Jan;64(1):1-6. PMID 2420426

- ↑ Klous MG, Van den Brink W, Van Ree JM, Beijnen JH. "Development of pharmaceutical heroin preparations for medical co-prescription to opioid dependent patients." Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005 December 12;80(3):283-95. PMID 15916865. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.008

- ↑ David Shewan, Phil Dalgarno (2005). "Evidence for controlled heroin use? high levels of negative health and social outcomes among non-treatment heroin users in Glasgow" (PDF). British Journal of Health Psychology. 10: 33–48. doi:10.1348/135910704X14582.

- ↑ Hamish Warburton, Paul J Turnbull, Mike Hough (2005). "Occasional and controlled heroin use: Not a problem?".

- ↑ "Yellow List: List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. December 2004. Unknown parameter

|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) Referring URL = http://www.incb.org/incb/yellow_list.html - ↑ "Opium Throughout History". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ↑ Wright, C.R.A. (2003-08-12). "On the Action of Organic Acids and their Anhydrides on the Natural Alkaloids". Archived from the original on 2004-06-06. Check date values in:

|date=(help) Note: this is an annotated excerpt of Wright, C.R.A. (1874). "On the Action of Organic Acids and their Anhydrides on the Natural Alkaloids". Journal of the Chemical Society. 27: 1031–1043. - ↑ owden, Mary Ellen. Pharmaceutical Achievers. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation, 2002.

- ↑ "How aspirin turned hero". Sunday Times. 1998. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Treaty of Versailles". 1919-06-28. pp. Part X, Section IV, Annex, paragraph 5. Retrieved 2007-05-05. Check date values in:

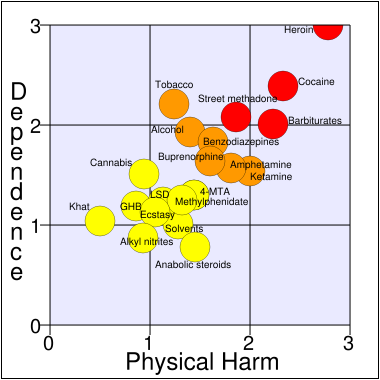

|date=(help) - ↑ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ Tschacher W, Haemmig R, Jacobshagen N. (2003). "Time series modeling of heroin and morphine drug action". Psychopharmacology. PMID 12404073.

- ↑ W. R. Martin 1 and H. F. Fraser 1

- ↑ 1 National Institute of Mental Health, Addiction Research Center, U. S. Public Health Service Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky

- ↑ Journal of Pharmacology And Experimental Therapeutics, Vol. 133, Issue 3, pp. 388-399, 1961

- ↑ Notes on heroin dosage & tolerance. Erowid's Vault, 2001.

- ↑ First murder charge over heroin mix that killed 400 - World - Times Online

- ↑ Nazemroaya, Mahdi Darius (2006). "The War in Afghanistan: Drugs, Money Laundering and the Banking System". GlobalResearch.ca. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Afghanistan opium survey - 2004" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ↑ McGirk, Tim (2004). "Terrorism's Harvest: How al-Qaeda is tapping into the opium trade to finance its operations and destabilize Afghanistan". Time Magazine Asia. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gall, Carolotta (2006). "Opium Harvest at Record Level in Afghanistan". New York Times - Asia Pacific. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Cat.Inist

- ↑ Healthy Living - Preserving Kidney Function

- ↑ Kidneys Edmonton Alberta Kidney Foundation Canada

- ↑ National Kidney Foundation: How Your Kidneys Work

- ↑ NIDDK Clearinghouses Publications Catalog

- ↑ Shane Darke, Deborah Zador (1996). "Fatal Heroin 'Overdose': a Review". Addiction. 91 (12): 1765–1772.

- ↑ http://lincoln.pps.k12.or.us/lscheffler/ToxicSubstances%20in%20water.htm

- ↑ The "heroin overdose" mystery and other occupational hazards of addiction, Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

- ↑ "A case report: Pavlovian conditioning as a risk factor of heroin 'overdose' death". Harm Reduct J. 2 (11). 2005. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-2-11. Unknown parameter

|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ heroin addiction treatment by drug addiction treatment.info

- ↑ Adult Health Advisor 2005.4: Narcotic Drug Withdrawal

- ↑ Thomas, Josephine (May 2001). "Buprenorphine Proves Effective, Expands Options For Treatment of Heroin Addiction" (PDF). NIDA Notes: Articles that address research on Heroin. National Institute on Drug Abuse. p. 23. Unknown parameter

|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) - ↑ H.S. Lotsof. Ibogaine in the Treatment of Chemical Dependence Disorders: Clinical Perspectives. MAPS Bulletin 1995 V(3):19-26

- ↑ Nils Bejerot: The Swedish Addiction Epidemic in global perspective

- ↑ Goldacre, Ben (1998). "Methadone and Heroin: An Exercise in Medical Scepticism". Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- ↑ Nadelmann, Ethan (1995). "Switzerland's Heroin Experiment". Drug Policy Alliance. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Heroin prescription 'cuts costs'". BBC News. 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "About the study". North American Opiate Medication Initiative. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ↑ "Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis" (PDF). The Lancet. 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Brown, Robin (2006-05-04). "Heroin's Hell". The News Journal. pp. A1, A12. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Literature

- Diary Of A Drug Fiend by Aleister Crowley (1922)

- Heroin (1998) ISBN 1-56838-153-0

- Heroin Century (2002) ISBN 0-415-27899-6

- This is Heroin (2002) ISBN 1-86074-424-9

- The Heroin User's Handbook by Francis Moraes (paperback 2004) ISBN 1-55950-216-9

- The Little Book of Heroin by Francis Moraes (paperback 2000) ISBN 0-914171-98-4

- Heroin: A True Story of Addiction, Hope and Triumph by Julie O'Toole (paperback 2005) ISBN 1-905379-01-3

- The Heroin Diaries: A Year in the Life of a Shattered Rockstar by Nikki Sixx (2007) ISBN 978-0743486-28-6

bg:Хероин ca:Heroïna cs:Heroin da:Heroin de:Heroin et:Heroiin eo:Heroino eu:Heroina fa:هروئین gl:Heroína (droga) hr:Heroin id:Heroin is:Heróín it:Eroina he:הרואין lt:Heroinas hu:Heroin ms:Heroin nl:Heroïne no:Heroin nn:Heroin simple:Heroin sk:Heroín sl:Heroin sr:Хероин sh:Heroin fi:Heroiini sv:Heroin th:เฮโรอีน uk:Героїн

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 errors: dates

- E number from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Pages with broken file links

- Opioids

- Heroin

- Prodrugs

- Drugs

- Substance abuse

- Abuse