Congestive heart failure chronic pharmacotherapy

| Resident Survival Guide |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Rim Halaby, M.D. [2]

Overview

There are several goals in the chronic management of systolic heart failure. The management of diastolic heart failure is discussed elsewhere. One goal of therapy is to improve the patient's symptoms, exercise tolerance and quality of life. Diuretics, along with regular assessment of the patient's weight, minimizes fluid accumulation and the accompanying symptoms of dyspnea and orthopnea. Another goal is to reduce hospitalization and mortality. To achieve the second goal, patients with chronic heart failure should be administered an ACE inhibitor (or ARB if they are ACE intolerant) and a beta blocker. If the patient remains symptomatic, additional therapy may include an aldosterone antagonist.

Diuresis: First Step in the Management of Heart Failure

The treatment of chronic heart failure often begins with the administration of diuretics, particularly if the patient has signs or symptoms of volume overload. While increased left ventricular volume increases contractility to a point, if the heart is filled beyond that point, its contractility diminishes (the patient "falls of the Staring curve"). Diuretics can reduce volume overload and reduce shortness of breath and edema. There are three kinds of diuretics, loop diuretics, thiazides and potassium-sparing diuretics. Diuretics rapidly improve the symptoms of heart failure (within hours to days). Diuretics reduce excess volume that accumulates with heart failure and decrease pulmonary edema that causes symptoms of dyspnea and orthopnea[1]. Lasix 20 to 40 mg PO daily is a conventional starting dose, but in some patients, torsemide may be a better choice due to its more predictable absorption. Once a day dosing of a given diuretic is preferred to twice a day dosing at a lower dose. A rise in BUN and Cr may reflect a reduction in renal perfusion, and further diuresis should only be undertaken with careful monitoring of renal function. The patient should weigh themselves each morning at the same time on the same scale, and the diuretic dosing should be adjusted to maintain a constant weight. Given the risk of hypokalemia or hyperkalemia, the blood level of electrolyes should be checked regularly.

- Simultaneous With Initiating Diuresis

- Treat the underlying cause of heart failure such as ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and valvular heart disease.

- Treat other non cardiac diseases that might contribute to the symptoms of heart failure such as diabetes and hyperthyroidism[2].

- Treat with a low salt diet[3]

- Follow the patient's weight to check for fluid overload

- Treat with vaccines for influenza and pneumococcus [4][5]

ACE Inhibition and Angiotensin Receptor Blockade: Second Step in the Management of Heart Failure

After diuretics are started or at the same time they are started, an ACE inhibitor can be initiated [6]. This includes a large group of drugs, such as Enalapril (Vasotec/Renitec), Ramipril (Altace/Tritace/Ramace/Ramiwin), Quinapril (Accupril), Perindopril (Coversyl/Aceon), Lisinopril (Lisodur/Lopril/Novatec/Prinivil/Zestril) and Benazepril (Lotensin). They can improve symptoms and prognosis of heart failure in several ways including afterload reduction and favorable ventricular remodeling. Potential side effects of ACE inhibitors include dry cough and angioedema. Patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis or severe renal impairment are not appropriate for angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI).

During or after the initiation of diuresis, one could start, for example, lisinopril 5 mg Q day. Every 1 - 2 weeks, the dose would be escalated to achieve a target dose of 15 to 20 mg Q day. An ACE inhibitor is initiated before a beta blocker because an ACE inhibitor achieves its hemodynamic effect more rapidly, and is less likely to cause a decline in hemodynamics. Although there is some data to suggest that aspirin blunts the hemodynamic effect of ACE inhibitors, there is no data to suggest that aspirin reduces the clinical efficacy of ACE inhibitors in heart failure patients. Aspirin should be administered to patients with ischemic heart disease, but not to patients without it.

If a patient cannot tolerate a an ACE inhibitor (develops a cough), then an Angiotensin II receptor blocker can be administered in its place. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Blockade of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production / secretion of aldosterone. Because angiotensin II receptor antagonists do not inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin or other kinins, they are rarely associated with the persistent dry cough and/or angioedema, side effects which limit ACE inhibitor therapy. Commonly administered agents in the management of heart failure include Candesartan, Valsartan, Telmisartan, Losartan, Irbesartan, and Olmesartan. The effectiveness of switching to an ARB from and ACE inhibitor was demonstrated for candesartan in the CHARM Alternative trial [7].

In general, ARBs are as effective or slightly less effective than ACE inhibitors in the treatment of congestive heart failure.[8][9] It is a class 2a recommendation to substitute an ARB as an alternative to ACE inhibitors if the patient is already taking an ARB for another indication.[10]

The efficacy of adding an ARB to an ACE inhibitor was assessed in the CHARM Added trial[11]. While there was a reduction in the composite primary endpoint in the study, there was no reduction in mortality. Furthermore, the VALIANT trial demonstrated that an ARB should not be added to an ACE inhibitor in the post MI setting.

These negative results for adding ARBs on top of an ACE inhibitor in the post MI setting are in contrast to the results of the EMPHASIS HF trial which demonstrated that the addition of eplerenone (an aldosterone antagonist) to ACE inhibition improved clinical outcomes including mortality among patients with class II or III heart failure with a reduced LVEF.[12] Thus, based upon the mortality benefit observed in the EMPHASIS HF trial, an aldosterone antagonist rather than and ARB should be added to an ACE inhibitor in patients with

- NYHA class III or IV heart failure who has an LVEF < 35%

- NYHA class II heart failure and an LVEF < 30%

- Post-MI patient who has an LVEF < 40% who has heart failure symptoms or diabetes

"Triple therapy", the combined use of an ACE inhibitor, an ARB and an aldosterone antagonist is a relative contraindication.

Beta blockers: Third Step in the Management of Heart Failure

Beta blockers reduce the heart rate which lowers the myocardial energy expenditure. They also prolong diastolic filling and lengthen the period of coronary perfusion. Beta blockers can also decrease the toxicity of catecholamines on the myocardium.

Once you have achieved a stable dose of a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor, then one of the three beta blockers that have been associated with improved survival (carvedilol, metoprolol succinate or bisoprolol) can be added and the dose titrated based upon the patient's tolerance. You should avoid beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (pindolol or acebutolol). It should be noted that the 35% reduction in one year mortality observed in meta-analyses of beta-blockers in heart failure was when these drugs were added to ACE inhibitors[13]. There are no direct comparisons of the various beta-blockers, but some data does suggest that carvedilol may improve LVEF more than the others, but it may not be as well tolerated due to its vasodilatory properties. If the patient has been over diuresed, they may not tolerate the addition of a beta blocker.

- Relative contraindications to beta-blocker administration include the following:

- Asthma or bronchospasm

- Hypotension resulting in poor end organ perfusion or symptoms

- Bradycardia or heart block (first degree heart block with a PR interval > 0.24, second degree heart block, third degree heart block

- Peripheral arterial disease with limb ischemia at rest

- Moderate or greater peripheral edema

- Recent intravenous inotropic therapy

Given the potential for hemodynamic decompensation, the initiation of beta-blockers is best undertaken by an individual or center specializing in heart failure management. The patient should be aware of potential side effects, and should be aware that it may take one to three months for the beta-blockers to improve heart failure symptoms. Therapy is initiated with very low doses, and the dose of the beta-blocker should be doubled every two weeks until the target dose is achieved or symptoms prevent further dose escalation.

- Carvedilol: Initial dose 3.125 mg twice daily, target dose 25 to 50 mg twice daily

- Metoprolol succinate: Initial dose 12.5 mg daily, target dose 200 mg daily

- Bisoprolol: Initial dose 1.25 mg daily, target dose 5 to 10 mg daily

Weight gain or peripheral edema that is not responsive to diuresis may require a reduction in the dose of beta-blockers.

Aldosterone Antagonism: Fourth Step in the Management of Heart Failure

An aldosterone antagonist can be added to the regimen of 'select' patients. These selected patients include:

- Class III/IV heart failure and a LVEF <35%

- Class II heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%

- Post ST segment elevation MI and a LVEF < 40% who have either symptomatic heart failure or diabetes.

- The serum potassium must be under 5.0 meq/li and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) should be > 30 cc per minute

A requirement for aldosterone antagonist is that the patient's renal function and potassium can be carefully monitored. Eplerenone has fewer endocrine side effects (1%) than spironolactone (10%), but is more costly. A reasonable strategy is to initiate therapy with spironolactone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily, and then switch to eplerenone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily if endocrine side effects develop.

Risk Factors for the Development of Hyperkalemia on an Aldosterone Antagonist

- Triple therapy with an ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker makes this combination a contraindication

- Higher doses of either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

- Hyperkalemia prior to initiation of spironolactone

- Comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic renal insufficiency

- Higher NYHA heart failure class

- Concomitant administration of beta blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or potassium supplements

- A daily dose of Spironolactone greater than 50 mg

The Combination of Hydralazine and a Nitrate: Fifth step in the Management of Heart Failure

The combination of hydralazine and a nitrate (particularly among black patients) can be added if the patient continues to have symptoms on a diuretic, ACE inhibitor (or ARB in the intolerant patient) and a beta blocker. The initial dose is isosorbide dinitrate 20 mg three times a day along with hydralazine 25 mg three times a day. The dose(s) can be increased every 2 to 4 weeks to a target dose of isosorbide dinitrate 40 mg three times a day and hydralazine 75 mg three times a day.

Digoxin: Sixth step in the Management of Heart Failure

Digitalis can strengthen the contractility of the heart and can also be useful to achieve rate control in patients with heart failure who also have atrial fibrillation. In the DIG trial, digoxin reduced the rate of re-hospitalization but did not improve mortality among all patients enrolled in the trial.[14] However, in a retrospective analysis, mortality was reduced in male patients who had digoxin levels between 0.5 and 0.8 ng/mL and was increased in male patients with digoxin levels > 1.2 ng/ml.[15] A similar trend was observed among women patients: there was a trend towards lower mortality at digoxin concentrations between 0.5 to 0.9 ng/ml, but significantly higher mortality at digoxin concentrations > 1.2 ng/ml.[16]

Digoxin should not be used as primary therapy for congestive heart failure. The administration of digoxin is reasonable in patients with NYHA class II-IV heart failure symptoms who have an LVEF of < 40% despite treatment with diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, and an aldosterone antagonist. Small doses of 0.125 mg per day of digoxin are often effective in maintaining a serum digoxin level between 0.5 and 0.8 ng/ml.

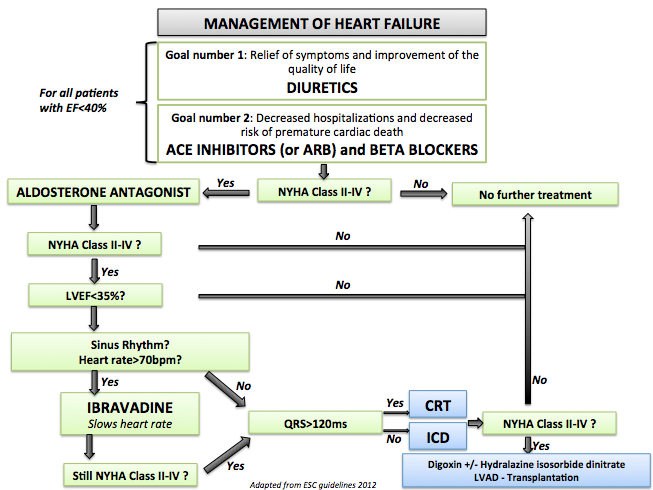

- Shown below is an image that summarizes the steps in the chronic management of patients with heart failure.

References

- ↑ Michael Felker G (2010). "Diuretic management in heart failure". Congest Heart Fail. 16 Suppl 1: S68–72. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00172.x. PMID 20653715.

- ↑ DeGroot WJ, Leonard JJ (1970). "Hyperthyroidism as a high cardiac output state". Am Heart J. 79 (2): 265–75. PMID 4903771.

- ↑ Evangelista LS, Shinnick MA (2008). "What do we know about adherence and self-care?". J Cardiovasc Nurs. 23 (3): 250–7. doi:10.1097/01.JCN.0000317428.98844.4d. PMC 2880251. PMID 18437067.

- ↑ Martins Wde A, Ribeiro MD, Oliveira LB, Barros Lda S, Jorge AC, Santos CM; et al. (2011). "Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in heart failure: a little applied recommendation". Arq Bras Cardiol. 96 (3): 240–5. PMID 21271169.

- ↑ Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Køber L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM (2003). "Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (20): 1893–906. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032292. PMID 14610160. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Shiokawa Y (1975). "Proceedings: Streptococcus surveys in Ryukyu Islands, Japan". Jpn Circ J. 39 (2): 168–71. PMID 1117548.

- ↑ Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K (2003). "Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial". Lancet. 362 (9386): 772–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. PMID 13678870. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Jong P, Demers C, McKelvie RS, Liu PP (2002). "Angiotensin receptor blockers in heart failure: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 39 (3): 463–70. PMID 11823085. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, Martinez FA, Dickstein K, Camm AJ, Konstam MA, Riegger G, Klinger GH, Neaton J, Sharma D, Thiyagarajan B (2000). "Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial--the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II". Lancet. 355 (9215): 1582–7. PMID 10821361. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW (2009). "2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation". Circulation. 119 (14): e391–479. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. PMID 19324966. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ McMurray JJ, Ostergren J, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA (2003). "Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial". Lancet. 362 (9386): 767–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14283-3. PMID 13678869. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B (2011). "Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009492. PMID 21073363. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Brophy JM, Joseph L, Rouleau JL (2001). "Beta-blockers in congestive heart failure. A Bayesian meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (7): 550–60. PMID 11281737. Retrieved 2013-04-28. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. The Digitalis Investigation Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (8): 525–33. 1997. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. PMID 9036306. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM (2003). "Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure". JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association. 289 (7): 871–8. PMID 12588271. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Adams KF, Patterson JH, Gattis WA, O'Connor CM, Lee CR, Schwartz TA, Gheorghiade M (2005). "Relationship of serum digoxin concentration to mortality and morbidity in women in the digitalis investigation group trial: a retrospective analysis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 46 (3): 497–504. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.091. PMID 16053964. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)