Aneurysm

| Aneurysm | |

| ICD-10 | I72 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 442 |

| DiseasesDB | 15088 |

| MedlinePlus | 001122 |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Aneurysm |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Aneurysm |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Aneurysm at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Aneurysm at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Aneurysm

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Aneurysm Risk calculators and risk factors for Aneurysm

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Aneurysm |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Aneurysm further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

An aneurysm (or aneurism) is a localized, blood-filled dilation (bulge) of a blood vessel caused by disease or weakening of the vessel wall.[1] Aneurysms most commonly occur in arteries at the base of the brain (the circle of Willis) and in the aorta (the main artery coming out of the heart), a so-called aortic aneurysm. The bulge in a blood vessel can burst and lead to death at any time. The larger an aneurysm becomes, the more likely it is to burst. Aneurysms can usually be treated.

Classification

Aneurysms may involve arteries or veins and have various causes. They are commonly further classified by shape, structure and location.

Shape

A saccular aneurysm resembles a small bubble that appears off the side of a blood vessel. The innermost layer of an artery, in direct contact with the flowing blood, is the tunica intima, commonly called the intima. Adjacent to this layer is the tunica media, known as the media and composed of smooth muscle cells and elastic tissue. The outermost layer is the tunica adventitia or tunica externa. This layer is composed of tougher connective tissue. A saccular aneurysm develops when fibers in the outer layer separate allowing the pressure of the blood to force the two inner layers to balloon through.

A fusiform aneurysm is a bulging around the entire circumference of the vessel without protrusion of the inner layers. It is shaped like a football or spindle.

These aneurysms can result from hypertension in conjunction with atherosclerosis that weakens the tunica adventitia, from congenital weakness of the adventitial layer (as in Marfan syndrome) or from infection.

Structure

In a true aneurysm the inner layers of a vessel have bulged outside the outer layer that normally confines them. The aneurysm is surrounded by these inner layers.

A false- or pseudoaneurysm does not primarily involve such distortion of the vessel. It is a collection of blood leaking completely out of an artery or vein, but confined next to the vessel by the surrounding tissue. This blood-filled cavity will eventually either thrombose (clot) enough to seal the leak or it will rupture out of the tougher tissue enclosing it and flow freely between layers of other tissues or into looser tissues. Pseudoaneurysms can be caused by trauma that punctures the artery and are a known complication of percutaneous arterial procedures such as arteriography or of arterial grafting or of use of an artery for injection, such as by drug abusers unable to find a usable vein. Like true aneurysms they may be felt as an abnormal pulsatile mass on palpation.

Location

Most non-intracranial aneurysms (94%) arise distal to the origin of the renal arteries at the infrarenal abdominal aorta, a condition mostly caused by atherosclerosis. The thoracic aorta can also be involved. One common form of thoracic aortic aneurysm involves widening of the proximal aorta and the aortic root, which leads to aortic insufficiency. Aneurysms occur in the legs also, particularly in the deep vessels (e.g., the popliteal vessels in the knee). Arterial aneurysms are much more common, but venous aneurysms do happen (for example, the popliteal venous aneurysm).

- While most aneurysms occur in an isolated form, the occurrence of berry aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery of the circle of Willis is associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).

- The third stage of syphilis also manifests as aneurysm of the aorta, which is due to loss of the vasa vasorum in the tunica adventitia.

Causes

- Familial

- Hypertension

- Trauma

- Collagen disorder

- Lipid metabolism

- Infection, inflammation

Risks

Rupture and blood clotting are the risks involved with aneurysms. Rupture leads to drop in blood pressure, rapid heart rate, and lightheadedness. The risk of death is high except for rupture in the extremities.

Blood clots from popliteal arterial aneurysms can travel downstream and impair perfusion to tissue. Only if the resulting pain and/or numbness are ignored over a significant period of time will such extreme results as amputation be needed. Clotting in popliteal venous aneurysms are much more serious as the clot can embolise and travel to the heart, or through the heart to the lungs (a pulmonary embolism).

Risk factors for an aneurysm are:

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Tobacco smoking

- Alcoholism

- Arteriosclerosis

- Lipid metabolism disorder

- Male gender

- Increasing age

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Complete Differential Diagnosis

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm

- Marfan's syndrome

- Trauma

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Infection

- Syphilis

- Other bacterial or mycotic infections

- Degenerative changes

- Arteriosclerosis

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Inflammation

- Hypertension

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

- Polycystic disease

- Marfan's syndrome

- Atherosclerosis

- Lipid metabolism disorders

- Hypertension

- Aortic dissection

- Mycotic infection

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Peripheral Arteries

Coronary Arteries

- Atherosclerosis

- Bacterial infection

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Congenital syphilis

- Scleroderma

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Septic emboli

- Kawasaki disease

Examples

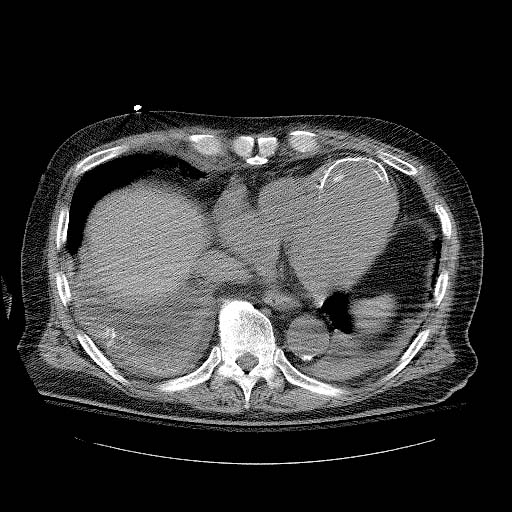

-

Computerized Tomography image shows a left ventricular apical aneurysm. Complication of acute myocardial infarction.

-

Chest X-Ray: Calcified ventricular aneurysm

-

Computerized Tomography: Calcified ventricular aneurysm

-

Computerized Tomography: Calcified ventricular aneurysm

Formation

Most frequent site of occurrence is in the anterior cerebral artery from the circle of Willis. The occurrence and expansion of an aneurysm in a given segment of the arterial tree involves local hemodynamic factors and factors intrinsic to the arterial segment itself.

The human aorta is a relatively low-resistance circuit for circulating blood. The lower extremities have higher arterial resistance, and the repeated trauma of a reflected arterial wave on the distal aorta may injure a weakened aortic wall and contribute to aneurysmal degeneration. Systemic hypertension compounds the injury, accelerates the expansion of known aneurysms, and may contribute to their formation.

Aneurysm formation is probably the result of multiple factors affecting that arterial segment and its local environment.

Hemodynamically, the coupling of aneurysmal dilation and increased wall stress is approximated by the law of Laplace. Specifically, the Laplace law states that the (arterial) wall tension is proportional to the pressure times the radius of the arterial conduit (T = P X R). As diameter increases, wall tension increases, which contributes to increasing diameter. As tension increases, risk of rupture increases. Increased pressure (systemic hypertension) and increased aneurysm size aggravate wall tension and therefore increase the risk of rupture. In addition, the vessel wall is supplied by the blood within its lumen in humans. Therefore in a developing aneurysm, the most ischemic portion of the aneurysm is at the farthest end, resulting in weakening of the vessel wall there and aiding further expansion of the aneurysm. Thus eventually all aneurysms will, if left to complete their evolution, rupture without intervention. In dogs, collateral vessels supply the vessel and aneurysms are rare.

Treatment of Aneurysms

Historically, the treatment of arterial aneurysms has been surgical intervention, or watchful waiting in combination with control of blood pressure. Recently, endovascular or minimally invasive techniques have been developed for many types of aneurysms.

Treatment of Brain Aneurysms

Currently there are two treatment options for brain aneurysms: surgical clipping or endovascular coiling. Surgical clipping was introduced by Walter Dandy of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1937. It consists of performing a craniotomy, exposing the aneurysm, and closing the base of the aneurysm with a clip. The surgical technique has been modified and improved over the years. Surgical clipping remains the best method to permanently eliminate aneurysms. Endovascular coiling was introduced by Guido Guglielmi at UCLA in 1991. It consists of passing a catheter into the femoral artery in the groin, through the aorta, into the brain arteries, and finally into the aneurysm itself. Once the catheter is in the aneurysm, platinum coils are pushed into the aneurysm and released. These coils initiate a clotting or thrombotic reaction within the aneurysm that, if successful, will eliminate the aneurysm. In the case of broad-based aneurysms, a stent is passed first into the parent artery to serve as a scaffold for the coils ("stent-assisted coiling").

At this point it appears that the risks associated with surgical clipping and endovascular coiling, in terms of stroke or death from the procedure, are the same. The major problem associated with endovascular coiling, however, is the high recurrence rate and subsequent bleeding of the aneurysms. For instance, the most recent study by Jacques Moret and colleagues from Paris, France, (a group with one of the largest experiences in endovascular coiling) indicates that 28.6% of aneurysms recurred within one year of coiling, and that the recurrence rate increased with time. (Piotin M et al., Radiology 243(2):500-508, May 2007) These results are similar to those previously reported by other endovascular groups. For instance Jean Raymond and colleagues from Montreal, Canada, (another group with a large experience in endovascular coiling) reported that 33.6% of aneurysms recurred within one year of coiling. (Raymond J et al., Stroke 34(6):1398-1403, June 2003) The long-term coiling results of one of the two prospective, randomized studies comparing surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling, namely the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) are turning out to be similarly worrisome. In ISAT, the need for late retreatment of aneurysms was 6.9 times more likely for endovascular coiling as compared to surgical clipping. (Campi A et al., Stroke 38(5):1538-1544, May 2007)

Therefore it appears that although endovascular coiling is associated with a shorter recovery period as compared to surgical clipping, it is also associated with a significantly higher recurrence and bleeding rate after treatment. Patients who undergo endovascular coiling need to have annual studies (such as MRI/MRA, CTA, or angiography) indefinitely to detect early recurrences. If a recurrence is identified, the aneurysm needs to be retreated with either surgery or further coiling. The risks associated with surgical clipping of previously-coiled aneurysms are very high. Ultimately, the decision to treat with surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling should be made by a cerebrovascular team with extensive experience in both modalities. At present it appears that only older patients with aneurysms that are difficult to reach surgically are more likely to benefit from endovascular coiling. These generalizations, however, are difficult to apply to every case, which is reflected in the wide variabilty internationally in the use of surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling.

Treatment of peripheral aneurysms

For aortic aneurysms or aneurysms that happen in the vessels that supply blood to the arms, legs, and head (the peripheral vessels), surgery involves replacing the weakened section of the vessel with an artificial tube, called a graft. More recently, covered metallic stent grafts can be inserted through the arteries of the leg and deployed across the aneurysm.

See also

- Aortic aneurysm

- Aortic dissection

- Cerebral aneurysm

- Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms

- Rasmussen's aneurysm

- Aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva

References

External links

- Addressing the Challenges Faced as a Result of Brain Haemorrhage

- Brain Blood Vessel Disorder Help & Info Site

- @neurIST - Integrated Biomedical Informatics for the Management of Cerebral Aneurysms

- Story of Aneurysm Survival

ar:تمدد الأوعية الدموية ast:Aneurisma bg:Аневризма de:Aneurysma it:Aneurisma nl:Aneurysma no:Aneurisme nn:Aneurisme simple:Aneurysm fi:Aneurysma sv:Artärbråck uk:Аневризма