Venezuelan equine encephalitis

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Anthony Gallo, B.S. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: VEE; VEEV; Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; Venezuelan encephalitis; Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis; Venezuelan equine fever

Overview

Venezuelan equine encephalitis is a mild to moderate, though sometimes fatal, infection of the central nervous system. Venezuelan equine encephalitis belongs to the Group IV positive-sense ssRNA virus within the Togaviridae family of viruses, and the genus Alphavirus. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is usually transmitted via mosquitos to the human host, primarily Culex melanoconion or Aedes. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus must be differentiated from other diseases that cause fever, headache, seizures, and altered mental status. Prognosis for Venezuelan equine encephalitis is generally good; less than 1% of patients infected with the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus present with symptoms. Symptomatic patients often recover within 2-3 weeks of infection. The case-fatality rate of Venezuelan equine encephalitis is approximately 0.7. If possible, a detailed and thorough history from the patient is necessary. If the patient is female, a pregnancy test should be administered to monitor for potential miscarriage. Venezuelan equine encephalitis is usually asymptomatic. The diagnostic method of choice for Venezuelan equine encephalitis is laboratory testing. There is no treatment for Venezuelan equine encephalitis; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care. There is a vaccination approved for limited use for Venezuelan equine encephalitis, though its effectiveness is often questioned.

Historical Perspective

Venezuelan equine encephalitis was first discovered in 1938 after the virus was isolated from the brains of dead horses following an outbreak in the Venezuelan countryside.[1] There have been several outbreaks of Venezuelan equine encephalitis. In 1995, the last major outbreak occurred in Venezuela and Columbia and resulted in approximately 75,000 cases, of which 3,000 had severe neurological complications and 300 progressed to mortality.[2] The last reported case of Venezuelan equine encephalitis in the United States occurred in southern Texas in 1972.[3]

Classification

Venezuelan equine encephalitis may be classified according to location of the disease into 2 subtypes: systemic or encephalitic. Venezuelan equine encephalitis may also be classified according to neuroinvasiveness of the disease into 2 subtypes: neuroinvasive and non-neuroinvasive.[4] Venezuelan equine encephalitis belongs to the Group IV positive-sense ssRNA virus within the Togaviridae family of viruses, and the genus Alphavirus. Venezuelan equine encephalitis is closely related to eastern equine encephalitis virus and western equine encephalitis virus. Venezuelan equine encephalitis is known as an arbovirus, or an arthropod-borne virus.

Pathophysiology

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is usually transmitted via mosquitos to the human host. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus contains positive-sense viral RNA; this RNA has its genome directly utilized as if it were mRNA, producing a single protein which is modified by host and viral proteins to form the various proteins needed for replication. The following table is a summary of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus:[5]

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Nucleic acid | RNA |

| Sense | ssRNA(+) |

| Virion | Enveloped |

| Capsid | Spherical |

| Symmetry | Yes; T=4 icosahedral |

| Capsid monomers | 240 |

| Monomer length (diameter) | 70 nm |

| Additional envelope information | 80 spikes; each spike is a trimer of E1/E2 proteins |

| Genome shape | Linear |

| Genome length | 11-12 kb |

| Nucleotide cap | Yes |

| Polyadenylated tail | Yes |

| Incubation period | 1-6 day(s) |

Venezuelan equine encephalitis is contracted by the bite of an infected mosquito, primarily Culex melanoconion or Aedes. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus circulates between a mosquito vector, usually Culex melanoconion, and forest rodents in Central and South America. Transmission to humans requires mosquito species capable of creating a "bridge" between infected animals and uninfected humans, such as some Aedes and other Culex species. The incubation period is 1-6 day(s).[7] In contrast to many other arboviral infections, infected humans possess sufficient viremia to infect uninfected mosquitos.[8] Additionally, while a link has never been proven, there is speculation that transmission between humans is possible, as 40% of cases demonstrate infection in the pharynx.[9]

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is transmitted in the following pattern:[5]

- Attachment of the viral E glycoprotein to host receptors mediates clathrin endocytosis of virus into the host cell.

- Fusion of virus membrane with the host cell membrane. RNA genome is released into the cytoplasm.

- The positive-sense ssRNA virus is translated into a polyprotein, which is cleaved into non-structural proteins necessary for RNA synthesis (replication and transcription).

- Replication takes place in cytoplasmic viral factories at the surface of endosomes. A dsRNA genome is synthesized from the genomic ssRNA(+).

- The dsRNA genome is transcribed thereby providing viral mRNAs (new ssRNA(+) genomes).

- Expression of the subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) gives rise to the structural proteins.

- Virus assembly occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum.

- Virions bud at the endoplasmic reticulum, are transported to the Golgi apparatus, and then exit the cell via the secretory pathway.

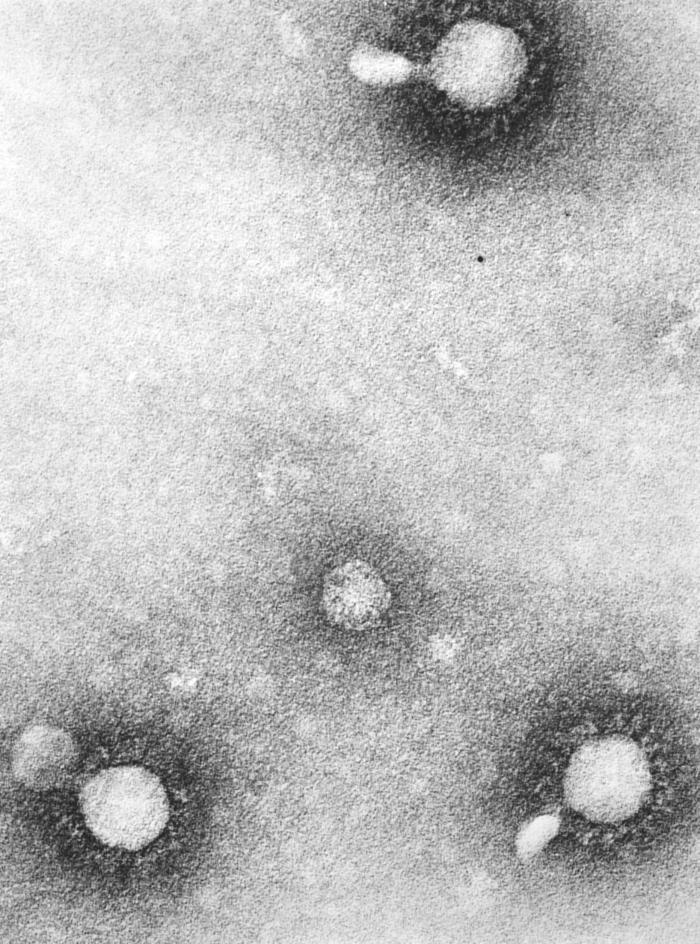

On microscopic histopathological analysis, the enveloped, spherical, and icosahedral virion shape are characteristic findings of Venezuelan equine encephalitis.

Causes

Venezuelan equine encephalitis may be caused by Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

Differentiating Venezuelan equine encephalitis from Other Diseases

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus must be differentiated from other diseases that cause fever, headache, seizures, and altered mental status, such as:[8][10][11][12][13]

| Disease | Similarities | Differentials |

|---|---|---|

| Meningitis | Classic triad of fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status | Photophobia, phonophobia, rash associated with meningococcemia, concomitant sinusitis or otitis, swelling of the fontanelle in infants (0-6 months) |

| Brain abscess | Fever, headache, hemiparesis | Varies depending on the location of the abscess; clinically, visual disturbance including papilledema, decreased sensation; on imaging, a lesion demonstrates both ring enhancement and central restricted diffusion |

| Demyelinating diseases | Ataxia, lethargy | Multiple sclerosis: clinically, nystagmus, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, Lhermitte's sign; on imaging, well-demarcated ovoid lesions with possible T1 hypointensities (“black holes”)

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: clinically, somnolence, myoclonic movements, and hemiparesis; on imaging, diffuse or multi-lesion enhancement, with indistinct lesion borders |

| Substance abuse | Tremor, headache, altered mental status | Varies depending on type of substance: prior history, drug-seeking behavior, attention-seeking behavior, paranoia, sudden panic, anxiety, hallucinations |

| Electrolyte disturbance | Fatigue, headache, nausea | Varies depending on deficient ions; clinically, edema, constipation, hallucinations; on EKG, abnormalities in T wave, P wave, QRS complex; possible presentations include arrhythmia, dehydration, renal failure |

| Stroke | Ataxia, aphasia, dizziness | Varies depending on classification of stroke; presents with positional vertigo, high blood pressure, extremity weakness |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | Headache, coma, dizziness | Lobar hemorrhage, numbness, tingling, hypertension, hemorrhagic diathesis |

| Trauma | Headache, altered mental status | Amnesia, loss of consciousness, dizziness, concussion, contusion |

Epidemiology and Demographics

The case-fatality rate of Venezuelan equine encephalitis is approximately 0.7.[14]

Age

Patients of all age groups may develop Venezuelan equine encephalitis.[2]

Gender

Venezuelan equine encephalitis affects men and women equally.[2]

Race

There is no racial predilection for Venezuelan equine encephalitis.

Seasonal

Venezuelan equine encephalitis is most commonly observed in the summer months or after periods of heavy rainfall.

Geographic Distribution

The majority of Venezuelan equine encephalitis cases are reported in South America, specifically Columbia and Venezuela.

Risk Factors

Common risk factors in the development of Venezuelan equine encephalitis are:

- Summer season

- Outdoor recreational activities

- Residing or visiting Central and South America

- Contact with:

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

If left untreated, patients with Venezuelan equine encephalitis may progress to febrile prodrome followed by meningismus, weakness, tremors, and altered mental status.

Complications

Complications of Venezuelan equine encephalitis include:

- Seizures

- Loss of basic motor skills

- Loss of coordination

- Meningitis

- Dysarthria

- Affective disorders

- Miscarriage in pregnant women

Prognosis

Prognosis for Venezuelan equine encephalitis is generally good; less than 1% of patients infected with the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus present with symptoms. Symptomatic patients often recover within 2-3 weeks of infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria

Neuroinvasive vs non-neuroinvasive Venezuelan equine encephalitis can be differentiated based on both clinical and laboratory findings. These include:[4]

| Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Subtype | Clinical Presentation | Laboratory Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroinvasive |

|

|

| Non-neuroinvasive |

|

|

History and Symptoms

If possible, a detailed and thorough history from the patient is necessary. If the patient is female, a pregnancy test should be administered to monitor for potential miscarriage. Venezuelan equine encephalitis is usually asymptomatic. Less common symptoms of Venezuelan equine encephalitis include:[8][15]

- Fever

- Chills

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Muscle pain

- Joint pain

- Throat pain

- Dizziness

- Light-sensitivity

- Altered mental status

Physical Examination

Physical examination for Venezuelan equine encephalitis may be remarkable for:[16]

- Fever

- Ataxia

- Seizures

- Obtundation

- Myalgia

- Acute flaccid myelitis

- Lethargy

- Meningism

- Photophobia

- Somnolence

- Coma

- Motor neuron dysfunction

- Tremor

- Pharyngeal pain

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

Laboratory Findings

The diagnostic method of choice for Venezuelan equine encephalitis is laboratory testing. The positive presence of IgM antibodies is diagnostic of Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Other laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of Venezuelan equine encephalitis include:[17]

- Serologic cross-reactivity

- Persistence of IgG and neutralizing antibodies

- Confirmation of arboviral-specific neutralizing antibodies in enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- In cerebrospinal fluid:

- Pleocytosis

- Increased protein levels

- Normal to slightly elevated glucose levels

Imaging Findings

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Findings of Venezuelan equine encephalitis on MRI include T2 hyperintensity and restricted diffusion in the basal ganglia and thalamus.[18] CT scan appears normal. EEG typically demonstrates diffuse slowing; some cases present with focal temporal slowing, resembling herpes simplex encephalitis.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

There is no treatment for Venezuelan equine encephalitis; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care. Because supportive care is the only treatment for Venezuelan equine encephalitis, physicians often do not request the tests required to specifically identify the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

Surgery

Surgical intervention is not recommended for the management of Venezuelan equine encephalitis.

Prevention

TC-83 is is a live, attenuated vaccine recommended for at risk military and laboratory personnel to prevent Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Mild to moderate adverse reactions have been noted in up to 25% of patients.[19] In some cases, the TC-83 strain does not provide sufficient immunization and may be bolstered with a C-84 vaccine. The vaccine has not been proven as fully effective against aerosol exposure.[20] Currently only the C-84 vaccine is licensed for use in horses in the United States, although countries, such as Mexico and Colombia, still produce the live vaccine for horses.

Other primary prevention strategies for Venezuelan equine encephalitis include:[21]

- Removal of standing water

- Screens on doors and windows

- When outdoors, wearing:

- Insect repellent containing DEET

- Long sleeves, pants; tucking in pants into high socks

References

- ↑ Beck CE, Wyckoff RW (1938). "VENEZUELAN EQUINE ENCEPHALOMYELITIS". Science. 88 (2292): 530. doi:10.1126/science.88.2292.530. PMID 17840536.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Rivas F, Diaz LA, Cardenas VM, Daza E, Bruzon L, Alcala A; et al. (1997). "Epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in La Guajira, Colombia, 1995". J Infect Dis. 175 (4): 828–32. PMID 9086137.

- ↑ Venezuelan Equine Encephalomyelitis - Fact Sheet. Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2012). http://www.inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/venezuelan-equine-encephalomyelitis/fact-sheet/eng/1329841926239/1329842048136 Accessed on March 31, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Arboviral diseases, neuroinvasive and non-neuroinvasive 2015 Case Definition. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Centers for Disease Control (2015). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/arboviral-diseases-neuroinvasive-and-non-neuroinvasive/case-definition/2015/ Accessed on March 31, 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Alphavirus. SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. http://viralzone.expasy.org/viralzone/all_by_species/625.html Accessed on March 15, 2016

- ↑ "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

- ↑ VENEZUELAN EQUINE ENCEPHALITIS VIRUS: PATHOGEN SAFETY DATA SHEET - INFECTIOUS SUBSTANCES. Public Health Agency of Canada. (2011) http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/ven-encephalit-eng.php Accessed on March 31, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 M.D. JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, Expert Consult Premium Edition. Saunders; 2014.

- ↑ Bowen GS, Calisher CH (1976). "Virological and serological studies of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis in humans". J Clin Microbiol. 4 (1): 22–7. PMC 274383. PMID 956360.

- ↑ Kennedy PG (2004). "Viral encephalitis: causes, differential diagnosis, and management". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 75 Suppl 1: i10–5. PMC 1765650. PMID 14978145.

- ↑ Arboviral Infections (arthropod-borne encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, California encephalitis, Powassan encephalitis, West Nile encephalitis). New York State Department of Health (2006). https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/arboviral/fact_sheet.htm Accessed on February 23, 2016

- ↑ Eckstein C, Saidha S, Levy M (2012). "A differential diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: beyond multiple sclerosis". J Neurol. 259 (5): 801–16. doi:10.1007/s00415-011-6240-5. PMID 21932127.

- ↑ De Kruijk JR, Twijnstra A, Leffers P (2001). "Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury". Brain Inj. 15 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1080/026990501458335. PMID 11260760.

- ↑ Weaver SC, Salas R, Rico-Hesse R, Ludwig GV, Oberste MS, Boshell J; et al. (1996). "Re-emergence of epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis in South America. VEE Study Group". Lancet. 348 (9025): 436–40. PMID 8709783.

- ↑ Meningitis and Encephalitis Fact Sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. National Institutes of Health (2015). http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/encephalitis_meningitis/detail_encephalitis_meningitis.htm Accessed on February 9, 2015

- ↑ Steele KE, Twenhafel NA (2010). "REVIEW PAPER: pathology of animal models of alphavirus encephalitis". Vet Pathol. 47 (5): 790–805. doi:10.1177/0300985810372508. PMID 20551475.

- ↑ The Management of Encephalitis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. http://www.idsociety.org/uploadedFiles/IDSA/Guidelines-Patient_Care/PDF_Library/Encephalitis.pdf Accessed on February 16, 2016.

- ↑ Flavivirus encephalitis. Radiopaedia.org (2016). http://radiopaedia.org/articles/flavivirus-encephalitis Accessed on March 29, 2016.

- ↑ Paessler S, Weaver SC (2009). "Vaccines for Venezuelan equine encephalitis". Vaccine. 27 Suppl 4: D80–5. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.095. PMC 2764542. PMID 19837294.

- ↑ Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. MicrobeWiki (2010) https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Venezuelan_equine_encephalitis_virus Accessed on April 5, 2016.

- ↑ Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE). New York State Department of Public Health (2012). https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/eastern_equine_encephalitis/fact_sheet.htm Accessed on March 15, 2016.