Diabetes mellitus type 2 pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

* In 1923, when Banting and Bests were awarded the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[insulin]] discovery, most researchers believed that this had led to a cure for [[diabetes]]. However, despite the advances in the [[Blood sugar|blood glucose]] management, there is no cure for [[diabetes]] or for the prevention of its major [[Complication (medicine)|complications]]. | * In 1923, when Banting and Bests were awarded the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[insulin]] discovery, most researchers believed that this had led to a cure for [[diabetes]]. However, despite the advances in the [[Blood sugar|blood glucose]] management, there is no cure for [[diabetes]] or for the prevention of its major [[Complication (medicine)|complications]]. | ||

* Scientists have observed that people with [[type 2 diabetes]] have overly active, and sometimes dysfunctional [[immune system]]<nowiki/>s, which are linked to some [[Complication (medicine)|complications]]. In current times, [[diabetes]] is seen as the disease of high blood [[glucose]], or lack of [[insulin]], however chronic [[Inflammation|inflammatory]] states and the overabundance of [[reactive oxygen species]] ([[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]]) also play a part in the disease process.<ref name="pmid14679177">{{cite journal| author=Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al.| title=Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. | journal=J Clin Invest | year= 2003 | volume= 112 | issue= 12 | pages= 1821-30 | pmid=14679177 | doi=10.1172/JCI19451 | pmc=PMC296998 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=14679177 }} </ref>. | * Scientists have observed that people with [[type 2 diabetes]] have overly active, and sometimes dysfunctional [[immune system]]<nowiki/>s, which are linked to some [[Complication (medicine)|complications]]. In current times, [[diabetes]] is seen as the disease of high blood [[glucose]], or lack of [[insulin]], however chronic [[Inflammation|inflammatory]] states and the overabundance of [[reactive oxygen species]] ([[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]]) also play a part in the disease process.<ref name="pmid14679177">{{cite journal| author=Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al.| title=Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. | journal=J Clin Invest | year= 2003 | volume= 112 | issue= 12 | pages= 1821-30 | pmid=14679177 | doi=10.1172/JCI19451 | pmc=PMC296998 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=14679177 }} </ref>. | ||

* [[Inflammation]] is part of a healthy immune response, an orchestrated onslaught of cells and chemicals that heal injury and fight [[infection]]. [[Chronic inflammation]] is a process which occurs throughout the body when a trigger activates the [[immune system]]. This inflammation results in the cascade of [[reactive oxygen species]] and further damage to tissue. <ref name="pmid14679177">{{cite journal| author=Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al.| title=Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. | journal=J Clin Invest | year= 2003 | volume= 112 | issue= 12 | pages= 1821-30 | pmid=14679177 | doi=10.1172/JCI19451 | pmc=PMC296998 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=14679177 }} </ref> <ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. | * [[Inflammation]] is part of a healthy immune response, an orchestrated onslaught of cells and chemicals that heal injury and fight [[infection]]. [[Chronic inflammation]] is a process which occurs throughout the body when a trigger activates the [[immune system]]. This inflammation results in the cascade of [[reactive oxygen species]] and further damage to tissue. <ref name="pmid14679177">{{cite journal| author=Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ et al.| title=Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. | journal=J Clin Invest | year= 2003 | volume= 112 | issue= 12 | pages= 1821-30 | pmid=14679177 | doi=10.1172/JCI19451 | pmc=PMC296998 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=14679177 }} </ref> <ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. | ||

* In 1993, scientists showed that the [[Tumour necrosis factor|tumor necrosis factor α]] ([[Tumor necrosis factor-alpha|TNF-α]]) expression was up-regulated in the [[adipose tissue]] of [[Obesity|obese]] mice with [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] <ref name="pmid7678183">{{cite journal| author=Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM| title=Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. | journal=Science | year= 1993 | volume= 259 | issue= 5091 | pages= 87-91 | pmid=7678183 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=7678183 }} </ref>. When mice deficient in [[Tumor necrosis factor-alpha|TNF-α]] were bred, [[diabetes]] did not develop. It appeared that [[inflammation]] preceded diabetes, long before [[diagnosis]]. | * In 1993, scientists showed that the [[Tumour necrosis factor|tumor necrosis factor α]] ([[Tumor necrosis factor-alpha|TNF-α]]) expression was up-regulated in the [[adipose tissue]] of [[Obesity|obese]] mice with [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] <ref name="pmid7678183">{{cite journal| author=Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM| title=Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. | journal=Science | year= 1993 | volume= 259 | issue= 5091 | pages= 87-91 | pmid=7678183 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=7678183 }} </ref>. When mice deficient in [[Tumor necrosis factor-alpha|TNF-α]] were bred, [[diabetes]] did not develop. It appeared that [[inflammation]] preceded diabetes, long before [[diagnosis]]. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

* [[Leukocytes]] and [[Innate immune system|innate immunity]] is the main source of [[inflammation]] in humans. In animal species, [[adipose tissue]] is the mediator of [[Innate immune system|innate immunity]]. In insects, [[adipocytes]] have a [[Receptor (biochemistry)|receptor]] for the cell wall of [[bacteria]] and [[fungi]], called [[TLR 1|toll like receptor]]. It is responsible for nuclear factor 1 β (NF1β) activation which induces the secretion of [[Antiseptic|antibacterial]] [[Peptide|peptides]] and other defense mechanisms. This induces the [[Inflammation|inflammatory]] cascades. [[Fat tissue]] also manages the storage of [[Lipid|lipids]] in the [[liver]] <ref name="pmid12881560">{{cite journal| author=Rolff J, Siva-Jothy MT| title=Invertebrate ecological immunology. | journal=Science | year= 2003 | volume= 301 | issue= 5632 | pages= 472-5 | pmid=12881560 | doi=10.1126/science.1080623 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=12881560 }} </ref>.However some aspects of [[innate immunity]] are still preserved in the [[Adipocyte|adipocytes]]. Moreover [[adipose tissue]] is populated with tissue resident [[macrophages]], which is significantly increased by diet induced [[weight gain]] <ref name="pmid15890981">{{cite journal| author=Berg AH, Scherer PE| title=Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. | journal=Circ Res | year= 2005 | volume= 96 | issue= 9 | pages= 939-49 | pmid=15890981 | doi=10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15890981 }} </ref>. | * [[Leukocytes]] and [[Innate immune system|innate immunity]] is the main source of [[inflammation]] in humans. In animal species, [[adipose tissue]] is the mediator of [[Innate immune system|innate immunity]]. In insects, [[adipocytes]] have a [[Receptor (biochemistry)|receptor]] for the cell wall of [[bacteria]] and [[fungi]], called [[TLR 1|toll like receptor]]. It is responsible for nuclear factor 1 β (NF1β) activation which induces the secretion of [[Antiseptic|antibacterial]] [[Peptide|peptides]] and other defense mechanisms. This induces the [[Inflammation|inflammatory]] cascades. [[Fat tissue]] also manages the storage of [[Lipid|lipids]] in the [[liver]] <ref name="pmid12881560">{{cite journal| author=Rolff J, Siva-Jothy MT| title=Invertebrate ecological immunology. | journal=Science | year= 2003 | volume= 301 | issue= 5632 | pages= 472-5 | pmid=12881560 | doi=10.1126/science.1080623 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=12881560 }} </ref>.However some aspects of [[innate immunity]] are still preserved in the [[Adipocyte|adipocytes]]. Moreover [[adipose tissue]] is populated with tissue resident [[macrophages]], which is significantly increased by diet induced [[weight gain]] <ref name="pmid15890981">{{cite journal| author=Berg AH, Scherer PE| title=Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. | journal=Circ Res | year= 2005 | volume= 96 | issue= 9 | pages= 939-49 | pmid=15890981 | doi=10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15890981 }} </ref>. | ||

* The first theory in regards to [[Adipose tissue|fat tissue]] being the source of [[inflammation]] and [[diabetes]], is that there is an overabundance of energy in the form of [[glucose]] and [[lipid]] in [[obesity]]. This leads to [[mitochondrial]] dysfunction and [[reactive oxygen species]] ([[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]]) production from the [[Adipocyte|adipocytes]]. [[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]] can activate the immunity by inducing the NF1β and hence secretion of the inflammatory [[Cytokine|cytokines]] <ref name="pmid15890981">{{cite journal| author=Berg AH, Scherer PE| title=Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. | journal=Circ Res | year= 2005 | volume= 96 | issue= 9 | pages= 939-49 | pmid=15890981 | doi=10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15890981 }} </ref>. The second [[theory]] is the [[Hypoxia (medical)|hypoxia]] theory reported by Trayhurn and Wood <ref name="pmid15469638">{{cite journal| author=Trayhurn P, Wood IS| title=Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. | journal=Br J Nutr | year= 2004 | volume= 92 | issue= 3 | pages= 347-55 | pmid=15469638 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15469638 }} </ref>. The [[fat]] cells expand when a person gains weight. These [[fat]] cells sometimes do not get enough [[oxygen]]. In response to [[Hypoxia (medical)|hypoxia]]; they induce [[cytokines]], which activate the [[angiogenesis]], [[metabolism]] and cellular stress. These [[Cytokine|cytokines]] induce [[insulin resistance]] and hence lead to [[diabetes]]. | * The first theory in regards to [[Adipose tissue|fat tissue]] being the source of [[inflammation]] and [[diabetes]], is that there is an overabundance of energy in the form of [[glucose]] and [[lipid]] in [[obesity]]. This leads to [[mitochondrial]] dysfunction and [[reactive oxygen species]] ([[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]]) production from the [[Adipocyte|adipocytes]]. [[Reactive oxygen species|ROS]] can activate the immunity by inducing the NF1β and hence secretion of the inflammatory [[Cytokine|cytokines]] <ref name="pmid15890981">{{cite journal| author=Berg AH, Scherer PE| title=Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. | journal=Circ Res | year= 2005 | volume= 96 | issue= 9 | pages= 939-49 | pmid=15890981 | doi=10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15890981 }} </ref>. The second [[theory]] is the [[Hypoxia (medical)|hypoxia]] theory reported by Trayhurn and Wood <ref name="pmid15469638">{{cite journal| author=Trayhurn P, Wood IS| title=Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. | journal=Br J Nutr | year= 2004 | volume= 92 | issue= 3 | pages= 347-55 | pmid=15469638 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15469638 }} </ref>. The [[fat]] cells expand when a person gains weight. These [[fat]] cells sometimes do not get enough [[oxygen]]. In response to [[Hypoxia (medical)|hypoxia]]; they induce [[cytokines]], which activate the [[angiogenesis]], [[metabolism]] and cellular stress. These [[Cytokine|cytokines]] induce [[insulin resistance]] and hence lead to [[diabetes]]. | ||

* The [[adipose tissue]] is not usually considered as an immune or inflammatory organ, however these observations provide evidence for the link between [[obesity]] and [[inflammation]]. | * The [[adipose tissue]] is not usually considered as an immune or inflammatory organ, however these observations provide evidence for the link between [[obesity]] and [[inflammation]]. | ||

====Systemic Inflammation in Diabetes==== | ====Systemic Inflammation in Diabetes==== | ||

* A growing body of evidence demonstrates that [[adipose tissue]] [[inflammation]] eventually results in systemic [[inflammation]]<ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. [[C-reactive protein|C reactive protein]] ([[C-reactive protein|CRP]]) is an inflammatory marker produced by the [[liver]] in response to [[TNFα]] and [[Interleukin 6|Interleukin-6]]. | * A growing body of evidence demonstrates that [[adipose tissue]] [[inflammation]] eventually results in systemic [[inflammation]]<ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. [[C-reactive protein|C reactive protein]] ([[C-reactive protein|CRP]]) is an inflammatory marker produced by the [[liver]] in response to [[TNFα]] and [[Interleukin 6|Interleukin-6]]. | ||

* [[CRP]] has been shown to precede [[diabetes]] years before diagnosis. Elevated [[C-reactive protein|CRP]] levels are unquestionably associated with [[obesity]] and increased risk of [[cardiovascular]] disorders. Patients with a high [[C-reactive protein|CRP]] levels are at a higher [[Mortality rate|mortality risk]] from [[heart]] disease. | * [[CRP]] has been shown to precede [[diabetes]] years before diagnosis. Elevated [[C-reactive protein|CRP]] levels are unquestionably associated with [[obesity]] and increased risk of [[cardiovascular]] disorders. Patients with a high [[C-reactive protein|CRP]] levels are at a higher [[Mortality rate|mortality risk]] from [[heart]] disease. | ||

* Other inflammatory markers are also disproportionately elevated in [[diabetes]] which results into systemic [[inflammation]]. The systemic [[inflammation]] result into [[insulin resistance]] and [[insulin resistance]] results into [[obesity]]. Hence both [[diabetes]] and [[inflammation]] reinforce each other via a positive feedback <ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. | * Other inflammatory markers are also disproportionately elevated in [[diabetes]] which results into systemic [[inflammation]]. The systemic [[inflammation]] result into [[insulin resistance]] and [[insulin resistance]] results into [[obesity]]. Hence both [[diabetes]] and [[inflammation]] reinforce each other via a positive feedback <ref name="pmid22252015">{{cite journal| author=Calle MC, Fernandez ML| title=Inflammation and type 2 diabetes. | journal=Diabetes Metab | year= 2012 | volume= 38 | issue= 3 | pages= 183-91 | pmid=22252015 | doi=10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22252015 }} </ref>. | ||

== Genetics == | == Genetics == | ||

[ | |||

* Variants in 11 [[genes]] have been related to [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes mellitus]] development. these genes include:<ref name="LyssenkoJonsson2008">{{cite journal|last1=Lyssenko|first1=Valeriya|last2=Jonsson|first2=Anna|last3=Almgren|first3=Peter|last4=Pulizzi|first4=Nicoló|last5=Isomaa|first5=Bo|last6=Tuomi|first6=Tiinamaija|last7=Berglund|first7=Göran|last8=Altshuler|first8=David|last9=Nilsson|first9=Peter|last10=Groop|first10=Leif|title=Clinical Risk Factors, DNA Variants, and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|volume=359|issue=21|year=2008|pages=2220–2232|issn=0028-4793|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0801869}}</ref> | |||

** ''[[TCF7L2]]'' | |||

** ''[[PPARG]],'' | |||

** ''[[FTO gene|FTO]],'' | |||

** ''KCNJ11,'' | |||

** ''[[NOTCH2]],'' | |||

** ''[[WFS1]],'' | |||

** ''[[CDKAL1]],'' | |||

** ''[[IGF2BP2]],'' | |||

** ''[[SLC30A8]],'' | |||

** ''[[JAZF1]],'' | |||

** ''[[HHEX]]'' | |||

* 8 variants of these [[genes]] are related to [[beta cell]] dysfunction.<ref name="LyssenkoJonsson20082">{{cite journal|last1=Lyssenko|first1=Valeriya|last2=Jonsson|first2=Anna|last3=Almgren|first3=Peter|last4=Pulizzi|first4=Nicoló|last5=Isomaa|first5=Bo|last6=Tuomi|first6=Tiinamaija|last7=Berglund|first7=Göran|last8=Altshuler|first8=David|last9=Nilsson|first9=Peter|last10=Groop|first10=Leif|title=Clinical Risk Factors, DNA Variants, and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|volume=359|issue=21|year=2008|pages=2220–2232|issn=0028-4793|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0801869}}</ref> | |||

== Associated Conditions == | == Associated Conditions == | ||

| Line 78: | Line 91: | ||

*[[Diabetes mellitus type 2]] is often associated with [[obesity]] and [[hypertension]] and elevated [[cholesterol]] ([[combined hyperlipidemia]]), and with the condition [[Metabolic syndrome]]. It is also associated with [[acromegaly]], [[Cushing's syndrome]], [[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease|Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis]]([[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease|NASH]]) and a number of other [[endocrinology|endocrinological]] disorders.<ref name="YounossiGolabi2019">{{cite journal|last1=Younossi|first1=Zobair M.|last2=Golabi|first2=Pegah|last3=de Avila|first3=Leyla|last4=Paik|first4=James Minhui|last5=Srishord|first5=Manirath|last6=Fukui|first6=Natsu|last7=Qiu|first7=Ying|last8=Burns|first8=Leah|last9=Afendy|first9=Arian|last10=Nader|first10=Fatema|title=The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=Journal of Hepatology|volume=71|issue=4|year=2019|pages=793–801|issn=01688278|doi=10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021}}</ref> | *[[Diabetes mellitus type 2]] is often associated with [[obesity]] and [[hypertension]] and elevated [[cholesterol]] ([[combined hyperlipidemia]]), and with the condition [[Metabolic syndrome]]. It is also associated with [[acromegaly]], [[Cushing's syndrome]], [[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease|Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis]]([[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease|NASH]]) and a number of other [[endocrinology|endocrinological]] disorders.<ref name="YounossiGolabi2019">{{cite journal|last1=Younossi|first1=Zobair M.|last2=Golabi|first2=Pegah|last3=de Avila|first3=Leyla|last4=Paik|first4=James Minhui|last5=Srishord|first5=Manirath|last6=Fukui|first6=Natsu|last7=Qiu|first7=Ying|last8=Burns|first8=Leah|last9=Afendy|first9=Arian|last10=Nader|first10=Fatema|title=The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=Journal of Hepatology|volume=71|issue=4|year=2019|pages=793–801|issn=01688278|doi=10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021}}</ref> | ||

*Additional factors found to increase risk of [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] include [[Ageing|aging]]<ref>Jack, L., Jr., Boseman, L. & Vinicor, F. Aging Americans and diabetes. A public health and clinical response. ''Geriatrics'' '''2004''', 59, 14-17.</ref>, high-[[fat]] diets<ref>Lovejoy, J. C. The influence of dietary fat on insulin resistance. ''Curr Diab Rep'' '''2002''', 2,435-440.</ref> and a less active lifestyle<ref>Hu, F. B. Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids 2003, 38,103-108.</ref>. | *Additional factors found to increase risk of [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] include [[Ageing|aging]]<ref>Jack, L., Jr., Boseman, L. & Vinicor, F. Aging Americans and diabetes. A public health and clinical response. ''Geriatrics'' '''2004''', 59, 14-17.</ref>, high-[[fat]] diets<ref>Lovejoy, J. C. The influence of dietary fat on insulin resistance. ''Curr Diab Rep'' '''2002''', 2,435-440.</ref> and a less active lifestyle<ref>Hu, F. B. Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids 2003, 38,103-108.</ref>. | ||

* There is a bidirectional relationship between [[Diabetes mellitus]] and [[sarcopenia]]. Numerous factors like accumulation of [[Advanced glycation endproduct|advanced glycation end-product]], [[inflammation]], [[insulin resistance]], vascular [[Complication (medicine)|complications]] and [[Oxidative stress|oxidative injury]] can interfere with muscle health. This impaired muscle health can eventually lead to [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]].<ref name="pmid31372016">{{cite journal| author=Mesinovic J, Zengin A, De Courten B, Ebeling PR, Scott D| title=Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional relationship. | journal=Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes | year= 2019 | volume= 12 | issue= | pages= 1057-1072 | pmid=31372016 | doi=10.2147/DMSO.S186600 | pmc=6630094 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=31372016 }}</ref> | * There is a bidirectional relationship between [[Diabetes mellitus]] and [[sarcopenia]]. Numerous factors like accumulation of [[Advanced glycation endproduct|advanced glycation end-product]], [[inflammation]], [[insulin resistance]], vascular [[Complication (medicine)|complications]] and [[Oxidative stress|oxidative injury]] can interfere with muscle health. This impaired muscle health can eventually lead to [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]].<ref name="pmid31372016">{{cite journal| author=Mesinovic J, Zengin A, De Courten B, Ebeling PR, Scott D| title=Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional relationship. | journal=Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes | year= 2019 | volume= 12 | issue= | pages= 1057-1072 | pmid=31372016 | doi=10.2147/DMSO.S186600 | pmc=6630094 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=31372016 }}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:58, 30 July 2020

|

Diabetes mellitus type 2 Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 from other Diseases |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Medical therapy |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Priyamvada Singh, M.B.B.S. [2]; Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3],Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [4]

Overview

The exact pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus is not fully understood. The underlying pathology is the development of insulin resistance. Contrary to type 1 diabetes, patients with type 2 diabetes sufficiently produce insulin. However, the cellular response to the circulating insulin is diminished in type 2 DM. The mechanism by which the insulin resistance develops is postulated to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Environmental influences on the pathogenesis of type 2 DM include high glycemic diets, central obesity, older age, male gender, low-fiber diet, and highly saturated fat diet.

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- The development of Insulin resistance is the underlying pathology; the cells in the body do not respond appropriately when insulin is present.

- Other important contributing factors:

- Increased hepatic glucose production (e.g., from glycogen degradation), especially at inappropriate times.

- Decreased insulin-mediated glucose transport in (primarily) muscle and adipose tissues (receptor and post-receptor defects).

- Impaired beta-cell function, loss of early phase of insulin release in response to hyperglycemic stimuli.

- Cancer survivors who received allogenic Hematopoeitic Cell Transplantation (HCT) are 3.65 times more likely to report type 2 diabetes than their siblings. Total body irradiation (TBI) is also associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes.

- This is a more complex problem than type 1 diabetes, but is sometimes easier to treat, especially in the initial years when insulin is often still being produced internally.

- Type 2 DM may go unnoticed for years in a patient before diagnosis, since the symptoms are typically milder (no ketoacidosis) and can be sporadic. However, severe complications can result from unnoticed type 2 diabetes, including renal failure, blindness, wounds that fail to heal, and coronary artery disease. The onset of the disease is most common in middle age and later life.

- Although primary Diabetes mellitus type 2 is presently of unknown etiology, there are some known etiologies responsible for the secondary diabetes mellitus. These known etiologies are known gene defects, trauma, surgery, hemochromatosis, pancreatic insufficiency, or certain types of medications (e.g. long-term steroid use).

- 23 years follow up in a study showed that enough level of tocopherol has been linked to lower risk of type 2 diabetes development.[1] Furthermore low level of vitamin E is related to increased risk of diabetes mellitus.[2] These data are suggestive of the role of dietary antioxidant and decreased risk of diabetes mellitus. Moreover animal models suggested the role of dietary antioxidants in suppressing the beta cell apoptosis due to oxidative stress.[3]

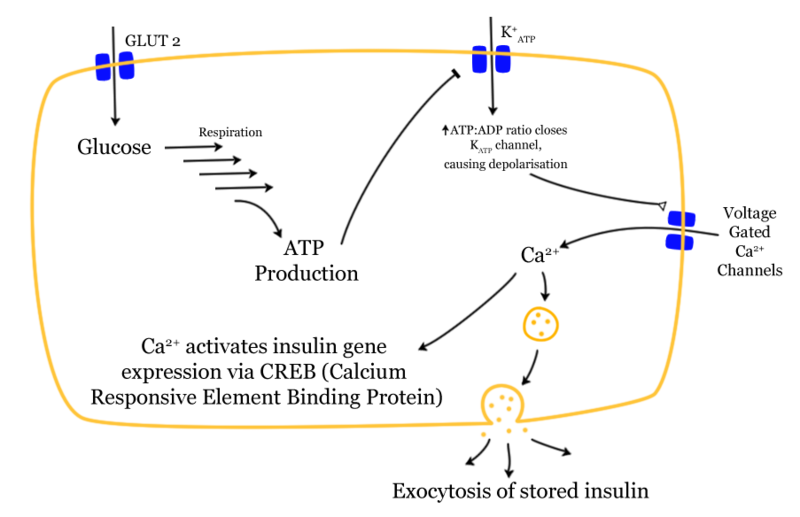

Beta-cell function

- Insulin production is more or less constant within the beta cells.

- It is stored within vacuoles pending release, via exocytosis, which is triggered by increased blood glucose levels.

- Insulin is the principal hormone that regulates uptake of glucose from the blood into most cells (primarily muscle and fat cells, but not central nervous system cells). Therefore deficiency of insulin or the insensitivity of its receptors plays a central role in all forms of diabetes mellitus.

- Much of the carbohydrate in food is converted within a few hours to the monosaccharide glucose, the principal carbohydrate found in blood and used by the body as fuel.

- Some carbohydrates are not converted e.g fruit sugar (fructose) is usable as cellular fuel but it is not converted to glucose, and it therefore does not participate in the insulin/glucose metabolic regulatory mechanism.

- Additionally, the carbohydrate cellulose (though it is actually many glucose molecules in long chains) is not converted to glucose, as humans and many animals have no digestive pathway capable of breaking up cellulose.

- Insulin is released into the blood by beta cells (β-cells), found in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, in response to rising levels of blood glucose after eating.

- Insulin is used by about two-thirds of the body's cells to absorb glucose from the blood for use as fuel, for conversion to other needed molecules, or for storage.

- Insulin is also the principal control signal for conversion of glucose to glycogen for internal storage in liver and muscle cells.

- Lowered glucose levels result both in the reduced release of insulin from the beta cells and in the reverse conversion of glycogen to glucose when glucose levels fall. This is mainly controlled byglucagon which acts in an opposite manner to insulin. Glucose thus recovered by the liver and re-enters the bloodstream; muscle cells lack the necessary export mechanism.

- Higher insulin levels increase some anabolic processes such as cell growth and duplication, protein synthesis, and fat storage. Insulin (or its lack) is the principal signal in converting many of the bidirectional processes of metabolism from a catabolic to an anabolic direction, and vice versa. In particular, a low insulin level is the trigger for entering or leaving ketosis (the fat burning metabolic phase).

- If the amount of insulin available is insufficient, if cells respond poorly to the effects of insulin (insulin insensitivity or resistance), or if the insulin itself is defective, then glucose will not be absorbed properly by those body cells that require it nor will it be stored appropriately in the liver and muscles. The net effect is persistent high levels of blood glucose, poor protein synthesis, and other metabolic derangements, such as acidosis.

Inflammation and Diabetes

- In 1923, when Banting and Bests were awarded the Nobel Prize for insulin discovery, most researchers believed that this had led to a cure for diabetes. However, despite the advances in the blood glucose management, there is no cure for diabetes or for the prevention of its major complications.

- Scientists have observed that people with type 2 diabetes have overly active, and sometimes dysfunctional immune systems, which are linked to some complications. In current times, diabetes is seen as the disease of high blood glucose, or lack of insulin, however chronic inflammatory states and the overabundance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) also play a part in the disease process.[4].

- Inflammation is part of a healthy immune response, an orchestrated onslaught of cells and chemicals that heal injury and fight infection. Chronic inflammation is a process which occurs throughout the body when a trigger activates the immune system. This inflammation results in the cascade of reactive oxygen species and further damage to tissue. [4] [5].

- In 1993, scientists showed that the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) expression was up-regulated in the adipose tissue of obese mice with type 2 diabetes [6]. When mice deficient in TNF-α were bred, diabetes did not develop. It appeared that inflammation preceded diabetes, long before diagnosis.

Obesity as the Link Between Diabetes and Inflammation

- Leukocytes and innate immunity is the main source of inflammation in humans. In animal species, adipose tissue is the mediator of innate immunity. In insects, adipocytes have a receptor for the cell wall of bacteria and fungi, called toll like receptor. It is responsible for nuclear factor 1 β (NF1β) activation which induces the secretion of antibacterial peptides and other defense mechanisms. This induces the inflammatory cascades. Fat tissue also manages the storage of lipids in the liver [7].However some aspects of innate immunity are still preserved in the adipocytes. Moreover adipose tissue is populated with tissue resident macrophages, which is significantly increased by diet induced weight gain [8].

- The first theory in regards to fat tissue being the source of inflammation and diabetes, is that there is an overabundance of energy in the form of glucose and lipid in obesity. This leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production from the adipocytes. ROS can activate the immunity by inducing the NF1β and hence secretion of the inflammatory cytokines [8]. The second theory is the hypoxia theory reported by Trayhurn and Wood [9]. The fat cells expand when a person gains weight. These fat cells sometimes do not get enough oxygen. In response to hypoxia; they induce cytokines, which activate the angiogenesis, metabolism and cellular stress. These cytokines induce insulin resistance and hence lead to diabetes.

- The adipose tissue is not usually considered as an immune or inflammatory organ, however these observations provide evidence for the link between obesity and inflammation.

Systemic Inflammation in Diabetes

- A growing body of evidence demonstrates that adipose tissue inflammation eventually results in systemic inflammation[5]. C reactive protein (CRP) is an inflammatory marker produced by the liver in response to TNFα and Interleukin-6.

- CRP has been shown to precede diabetes years before diagnosis. Elevated CRP levels are unquestionably associated with obesity and increased risk of cardiovascular disorders. Patients with a high CRP levels are at a higher mortality risk from heart disease.

- Other inflammatory markers are also disproportionately elevated in diabetes which results into systemic inflammation. The systemic inflammation result into insulin resistance and insulin resistance results into obesity. Hence both diabetes and inflammation reinforce each other via a positive feedback [5].

Genetics

- Variants in 11 genes have been related to type 2 diabetes mellitus development. these genes include:[10]

- 8 variants of these genes are related to beta cell dysfunction.[11]

Associated Conditions

- Diabetes mellitus type 2 is often associated with obesity and hypertension and elevated cholesterol (combined hyperlipidemia), and with the condition Metabolic syndrome. It is also associated with acromegaly, Cushing's syndrome, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis(NASH) and a number of other endocrinological disorders.[12]

- Additional factors found to increase risk of type 2 diabetes include aging[13], high-fat diets[14] and a less active lifestyle[15].

- There is a bidirectional relationship between Diabetes mellitus and sarcopenia. Numerous factors like accumulation of advanced glycation end-product, inflammation, insulin resistance, vascular complications and oxidative injury can interfere with muscle health. This impaired muscle health can eventually lead to type 2 diabetes.[16]

- Based on a review study using data from years 1990 to 2017, diabetes is linked to higher mortality from primary liver cancers. This study suggests diabetes as a significant risk factor for primary liver cancers.[17]

- Diabetic patients have higher concentration of bile acid in feeding state, compared to normal population. This change in bile acid level also showed some correlations with higher triglyceride level, insulin resistance index, blood pressure, and BMI.[18]

Gross Pathology

On gross pathology, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

Microscopic Pathology

On microscopic histopathological analysis, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

References

- ↑ Montonen, J.; Knekt, P.; Jarvinen, R.; Reunanen, A. (2004). "Dietary Antioxidant Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 27 (2): 362–366. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.2.362. ISSN 0149-5992.

- ↑ van der Schaft, Niels; Schoufour, Josje D.; Nano, Jana; Kiefte-de Jong, Jessica C.; Muka, Taulant; Sijbrands, Eric J. G.; Ikram, M. Arfan; Franco, Oscar H.; Voortman, Trudy (2019). "Dietary antioxidant capacity and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, prediabetes and insulin resistance: the Rotterdam Study". European Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (9): 853–861. doi:10.1007/s10654-019-00548-9. ISSN 0393-2990.

- ↑ Kaneto, H.; Kajimoto, Y.; Miyagawa, J.; Matsuoka, T.; Fujitani, Y.; Umayahara, Y.; Hanafusa, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Yamasaki, Y.; Hori, M. (1999). "Beneficial effects of antioxidants in diabetes: possible protection of pancreatic beta-cells against glucose toxicity". Diabetes. 48 (12): 2398–2406. doi:10.2337/diabetes.48.12.2398. ISSN 0012-1797.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ; et al. (2003). "Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance". J Clin Invest. 112 (12): 1821–30. doi:10.1172/JCI19451. PMC 296998. PMID 14679177.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Calle MC, Fernandez ML (2012). "Inflammation and type 2 diabetes". Diabetes Metab. 38 (3): 183–91. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2011.11.006. PMID 22252015.

- ↑ Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM (1993). "Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance". Science. 259 (5091): 87–91. PMID 7678183.

- ↑ Rolff J, Siva-Jothy MT (2003). "Invertebrate ecological immunology". Science. 301 (5632): 472–5. doi:10.1126/science.1080623. PMID 12881560.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Berg AH, Scherer PE (2005). "Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease". Circ Res. 96 (9): 939–49. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. PMID 15890981.

- ↑ Trayhurn P, Wood IS (2004). "Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue". Br J Nutr. 92 (3): 347–55. PMID 15469638.

- ↑ Lyssenko, Valeriya; Jonsson, Anna; Almgren, Peter; Pulizzi, Nicoló; Isomaa, Bo; Tuomi, Tiinamaija; Berglund, Göran; Altshuler, David; Nilsson, Peter; Groop, Leif (2008). "Clinical Risk Factors, DNA Variants, and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (21): 2220–2232. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801869. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Lyssenko, Valeriya; Jonsson, Anna; Almgren, Peter; Pulizzi, Nicoló; Isomaa, Bo; Tuomi, Tiinamaija; Berglund, Göran; Altshuler, David; Nilsson, Peter; Groop, Leif (2008). "Clinical Risk Factors, DNA Variants, and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (21): 2220–2232. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801869. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Younossi, Zobair M.; Golabi, Pegah; de Avila, Leyla; Paik, James Minhui; Srishord, Manirath; Fukui, Natsu; Qiu, Ying; Burns, Leah; Afendy, Arian; Nader, Fatema (2019). "The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Hepatology. 71 (4): 793–801. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021. ISSN 0168-8278.

- ↑ Jack, L., Jr., Boseman, L. & Vinicor, F. Aging Americans and diabetes. A public health and clinical response. Geriatrics 2004, 59, 14-17.

- ↑ Lovejoy, J. C. The influence of dietary fat on insulin resistance. Curr Diab Rep 2002, 2,435-440.

- ↑ Hu, F. B. Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids 2003, 38,103-108.

- ↑ Mesinovic J, Zengin A, De Courten B, Ebeling PR, Scott D (2019). "Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional relationship". Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 12: 1057–1072. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S186600. PMC 6630094 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 31372016. - ↑ Ge, Xiao-Jun; Du, Yu-Xuan; Zheng, Li-Mei; Wang, Mei; Jiang, Jun-Yao (2020). "Mortality trends of liver cancer among patients with type 2 diabetes at the global and national level". Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 34 (8): 107612. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107612. ISSN 1056-8727.

- ↑ Wu, Yingjie; Zhou, An; Tang, Li; Lei, Yuanyuan; Tang, Bo; Zhang, Linjing (2020). "Bile Acids: Key Regulators and Novel Treatment Targets for Type 2 Diabetes". Journal of Diabetes Research. 2020: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2020/6138438. ISSN 2314-6745.