Cirrhosis

| Cirrhosis | |

| |

|---|---|

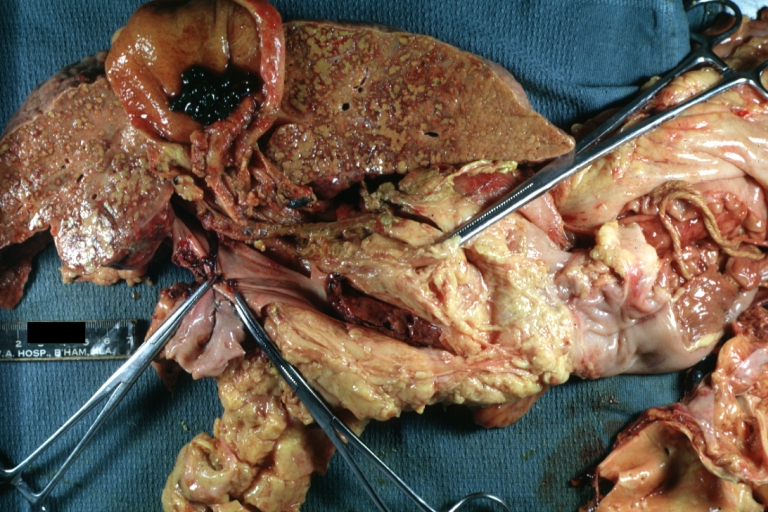

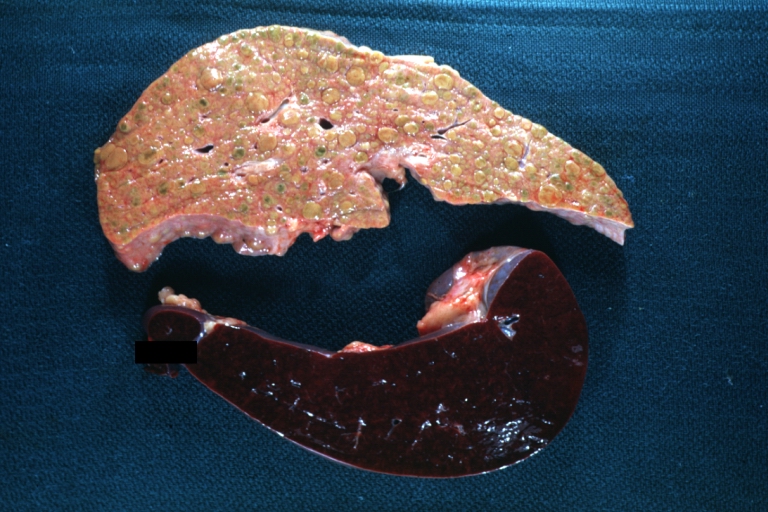

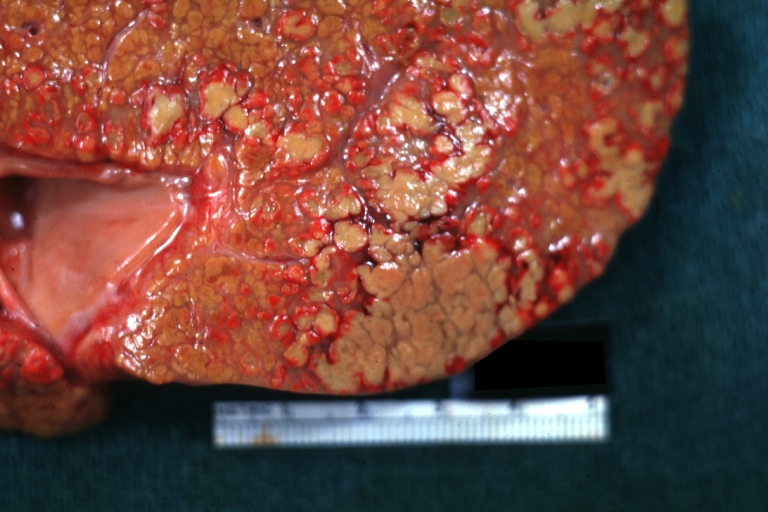

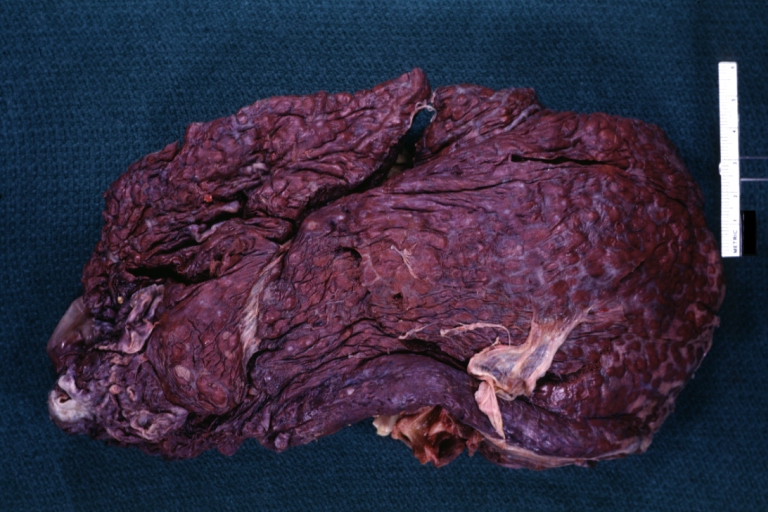

| Gross, natural color of liver and stomach view from external surfaces, micronodular cirrhosis and hemorrhagic gastritis (as the surgeon would see these in natural color). Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | K70.3, K71.7, K74 |

| ICD-9 | 571 |

| DiseasesDB | 2729 |

| MeSH | D008103 |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Cirrhosis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cirrhosis |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Cirrhosis |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Cirrhosis |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Cirrhosis at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Cirrhosis at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Cirrhosis

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Cirrhosis Discussion groups on Cirrhosis Directions to Hospitals Treating Cirrhosis Risk calculators and risk factors for Cirrhosis

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Cirrhosis |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]; Aditya Govindavarjhulla, M.B.B.S. [3]

Overview

Historical Perspective

Classification

Pathophysiology

Causes

Differential Diagnosis

Epidemiology and Demographics

Risk Factors

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms | Physical Examination |Laboratory tests | ECG | EEG | Chest X Ray |CT | MRI |Echocardiography or Ultrasound |Other imaging studies | Alternative diagnostics

Treatment

Medical therapy | Surgical options | Prevention | Financial costs| Future therapies

Natural history, Complications, Prognosis

Complications

As the disease progresses, complications may develop. In some people, these may be the first signs of the disease.

- Bruising and bleeding due to decreased production of coagulation factors.

- Jaundice due to decreased processing of bilirubin.

- Itching (pruritus) due to bile products deposited in the skin.

- Hepatic encephalopathy - the liver does not clear ammonia and related nitrogenous substances from the blood, which are carried to the brain, affecting cerebral functioning: neglect of personal appearance, unresponsiveness, forgetfulness, trouble concentrating, or changes in sleep habits.

- Sensitivity to medication due to decreased metabolism of the active compounds.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma is primary liver cancer, a frequent complication of cirrhosis. It has a high mortality rate.

- Portal hypertension - blood normally carried from the intestines and spleen through the hepatic portal vein flows more slowly and the pressure increases; this leads to the following complications:

- Ascites - fluid leaks through the vasculature into the abdominal cavity.

- Esophageal varices - collateral portal blood flow through vessels in the stomach and esophagus. These blood vessels may become enlarged and are more likely to burst.

- Problems in other organs.

- Cirrhosis can cause immune system dysfunction, leading to infection. Signs and symptoms of infection may be aspecific are more difficult to recognize (e.g. worsening encephalopathy but no fever).

- Fluid in the abdomen (ascites) may become infected with bacteria normally present in the intestines (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

- Hepatorenal syndrome - insufficient blood supply to the kidneys, causing acute renal failure. This complication has a very high mortality (over 50%).

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome - blood bypassing the normal lung circulation (shunting), leading to cyanosis and dyspnea(shortness of breath), characteristically worse on sitting up.[1]

- Portopulmonary hypertension - increased blood pressure over the lungs as a consequence of portal hypertension.[1]

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

| Well-Compensated, no EtOH | 35% mortality at 2 years |

| Onset of Ascites | 50% mortality at 2 years |

| Variceal bleeding | 65% mortality at 1 year (35% short-term mortality) |

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of cirrhosis is a liver biopsy, through a percutaneous, transjugular, laparoscopic, or fine-needle approach. Histologically cirrhosis can be classified as micronodular, macronodular, or mixed, but this classification has been abandoned since it is nonspecific to the etiology, it may change as the disease progresses, and serological markers are much more specific. However, a biopsy is not necessary if the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data suggests cirrhosis. Furthermore, there is a small but significant risk to liver biopsy, and cirrhosis itself predisposes for complications due to liver biopsy.[2]

Symptoms

- Lethargy

- Weakness

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite

Physical Exmination

The following signs and symptoms may occur in the presence of cirrhosis or as a result of the complications of cirrhosis. Many are nonspecific and may occur in other diseases and do not necessarily point to cirrhosis. Likewise, the absence of any does not rule out the possibility of cirrhosis.

Skin

- Spider angiomata or spider nevi. Vascular lesions consisting of central arteriole surrounded by many smaller vessels due to an increase in estradiol. These occur in about 33% of cases.[3]

- Palmar erythema. Exaggerations of normal speckled mottling of the palm, due to altered sex hormone metabolism.

- Nail changes.

- Muehrcke's nails - paired horizontal bands separated by normal color due to hypoalbuminemia (low production of albumin).

- Terry's nails - proximal two thirds of the nail plate appears white with distal one-third red, also due to hypoalbuminemia

- Clubbing --- Angle between the nail plate and proximal nail fold > 180 degrees

- Dupuytren's contracture. Thickening and shortening of palmar fascia that leads to flexion deformities of the fingers. Thought to be due to fibroblastic proliferation and disorderly collagen deposition. It is relatively common (33% of patients).

Eyes

- Jaundice. Yellow discoloring of the skin, eye, and mucus membranes due to increased bilirubin (at least 2-3 mg/dL or 30 mmol/L). Urine may also appear dark.

Abdomen

- Liver size. Can be enlarged, normal, or shrunken.

- Splenomegaly. Due to congestion of the red pulp as a result of portal hypertension.

- Ascites. Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity giving rise to flank dullness (needs about 1500 mL to detect flank dullness).

- Caput medusa. In portal hypertension, the umbilical vein may open. Blood from the portal venous system may be shunted through the periumbilical veins into the umbilical vein and ultimately to the abdominal wall veins, manifesting as caput medusa.

- Cruveilhier-Baumgarten murmur. Venous hum heard in epigastric region due to collateral connections between portal system and the remnant of the umbilical vein in portal hypertension.

Extremities

- Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Chronic proliferative periostitis of the long bones that can cause considerable pain.

Neurologic

- Asterixis. Bilateral asynchronous flapping of outstretched, dorsiflexed hands seen in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

Other

- Gynecomastia. Benign proliferation of glandular tissue of male breasts presenting with a rubbery or firm mass extending concentrically from the nipples. This is due to increased estradiol and can occur up to 66% of patients.

- Fetor hepaticus. Sweet pungent smell in breath due to increased dimethyl sulfide due to severe portal-systemic shunting.

Laboratory Findings

The following findings are typical in cirrhosis:

- Aminotransferases - AST and ALT are moderately elevated, with AST > ALT. However, normal aminotransferases do not preclude cirrhosis.

- Alkaline phosphatase - usually slightly elevated.

- GGT -- correlates with AP levels. Typically much higher in chronic liver disease from alcohol.

- Bilirubin - may elevate as cirrhosis progresses.

- Albumin - levels fall as the synthetic function of the liver declines with worsening cirrhosis since albumin is exclusively synthesized in the liver

- Prothrombin time - increases since the liver synthesizes clotting factors.

- Globulins - increased due to shunting of bacterial antigens away from the liver to lymphoid tissue.

- Serum sodium - hyponatremia due to inability to excrete free water resulting from high levels of ADH and aldosterone.

- Thrombocytopenia - due to both congestive splenomegaly as well as decreased thrombopoietin from the liver. However this rarely results in platelet count < 50,000/mL.

- Leukopenia and neutropenia - due to splenomegaly with splenic margination.

- Coagulation defects - the liver produces most of the coagulation factors and thus coagulopathy correlates with worsening liver disease.

Other laboratory studies performed in newly diagnosed cirrhosis may include:

- Serology for hepatitis viruses, autoantibodies (ANA, anti-smooth muscle, anti-mitochondria, anti-LKM)

- Ferritin and transferrin saturation (markers of iron overload), copper and ceruloplasmin (markers of copper overload)

- Immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgM, IgA) - these are non-specific but may assist in distinguishing various causes

- Cholesterol and glucose

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin

- Prothrombin time, albumin

- Platelets

- Lytes/Creatinine (Cr)

- Hyponatremia suggests severe disease

Imaging

Ultrasound is routinely used in the evaluation of cirrhosis, where it may show a small and nodular liver in advanced cirrhosis along with increased echogenicity with irregular appearing areas. Ultrasound may also screen for hepatocellular carcinoma, portal hypertension and Budd-Chiari syndrome (by assessing flow in the hepatic vein).

A new type of device, the FibroScan (transient elastography), uses elastic waves to determine liver stiffness which theoretically can be converted into a liver score based on the METAVIR scale. The FibroScan produces an ultrasound image of the liver (from 20-80mm) along with a pressure reading (in kPa.) The test is much faster than a biopsy (usually last 2.5-5 minutes) and is completely painless. It shows reasonable corellation with the severity of cirrhosis.[4]

Other tests performed in particular circumstances include abdominal CT and liver/bile duct MRI (MRCP).

Endoscopy

Gastroscopy (endoscopic examination of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum) is performed in patients with established cirrhosis to exclude the possibility of esophageal varices. If these are found, prophylactic local therapy may be applied (sclerotherapy or banding) and beta blocker treatment may be commenced.

Computer Tomography

-

Liver cirrhosis as seen on an axial CT of the abdomen.

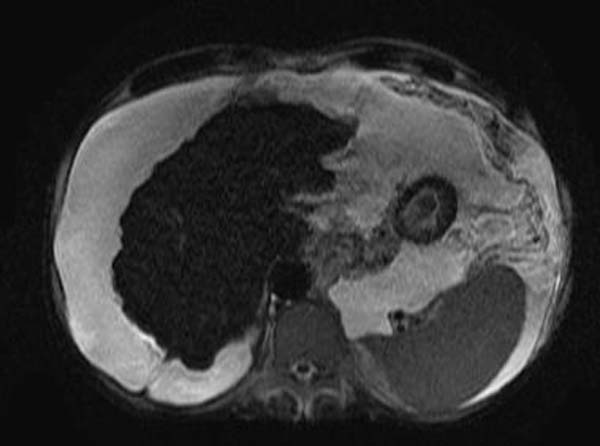

MRI

-

T2

-

T2

Other Diagnostic Modalities

If biliary pathology (primary sclerosing cholangitis - PSC) is suspected, ERCP may be performed.

Generally MRCP (MRI of biliary tract and pancreas) is sufficient for diagnosis, but ERCP allows for particular interventions, such as placement of a biliary stent or extraction of gallstones.

Pathology

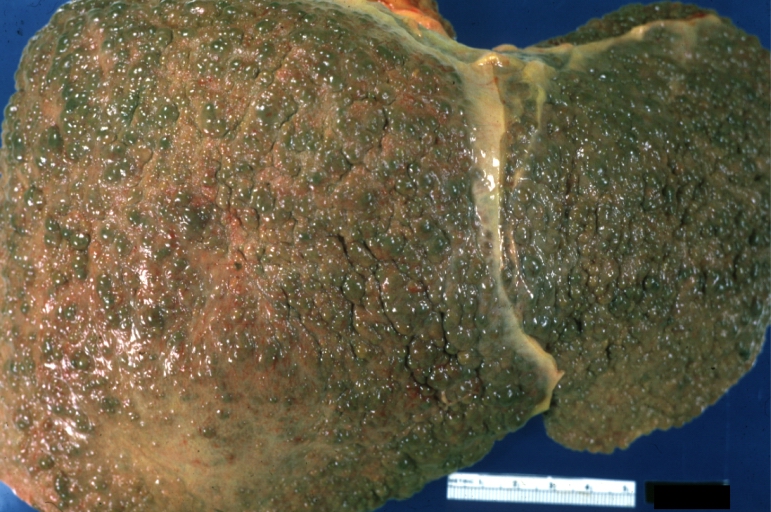

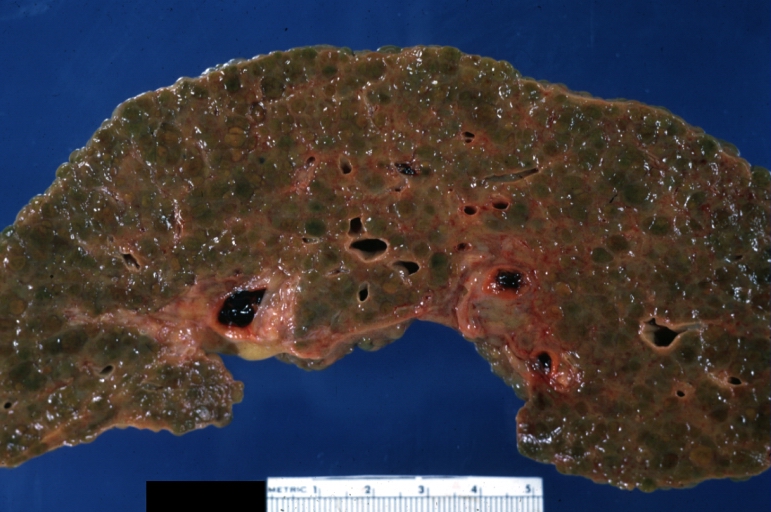

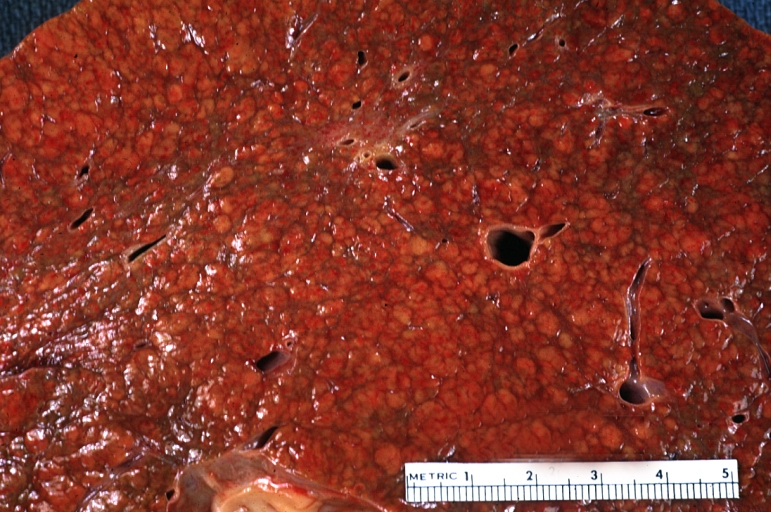

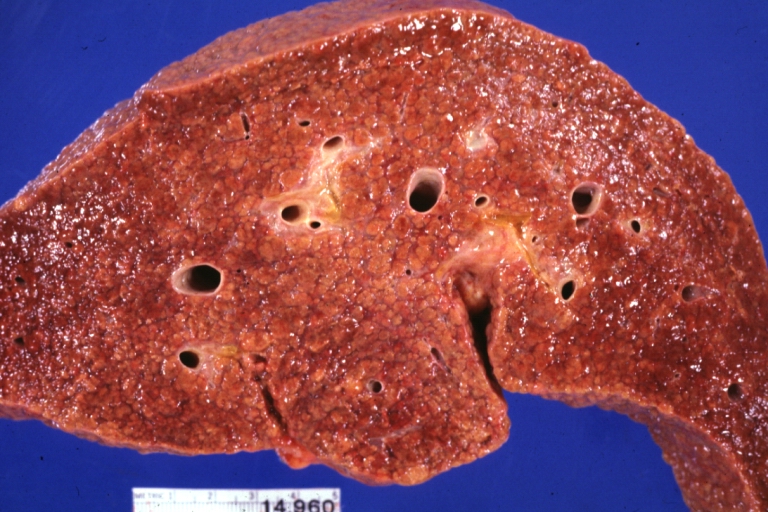

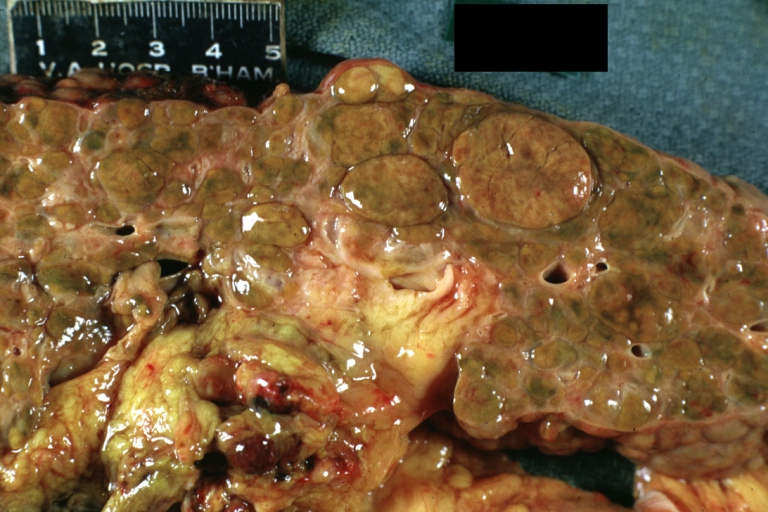

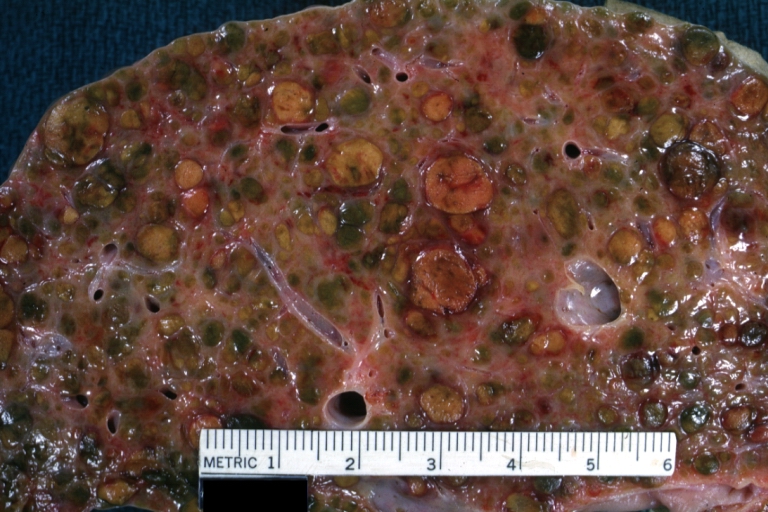

Macroscopically, the liver may be initially enlarged, but with progression of the disease, it becomes smaller. Its surface is irregular, the consistency is firm and the color is often yellow (if associates steatosis). Depending on the size of the nodules there are three macroscopic types: micronodular, macronodular and mixed cirrhosis. In micronodular form (Laennec's cirrhosis or portal cirrhosis) regenerating nodules are under 3 mm. In macronodular cirrhosis (post-necrotic cirrhosis), the nodules are larger than 3 mm. The mixed cirrhosis consists in a variety of nodules with different sizes.

Microscopically, cirrhosis is characterized by regeneration nodules, surrounded by fibrous septa. In these nodules, regenerating hepatocytes are disorderly disposed. Portal tracts, central veins and the radial pattern of hepatocytes are absent. Fibrous septa are important and may present inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes, macrophages) If it is a secondary biliary cirrhosis, biliary ducts are damaged, proliferated or distended - bile stasis. These dilated ducts contain inspissated bile which appear as bile casts or bile thrombi (brown-green, amorphous). Bile retention may be found also in the parenchyma, as the so called "bile lakes".[5]

Grading

The severity of cirrhosis is commonly classified with the Child-Pugh score. This score uses bilirubin, albumin, INR, presence and severity of ascites and encephalopathy to classify patients in class A, B or C; class A has a favourable prognosis, while class C is at high risk of death. It was devised in 1964 by Child and Turcotte and modified in 1973 by Pugh et al.[6]

More modern scores, used in the allocation of liver transplants but also in other contexts, are the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and its pediatric counterpart, the Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) score.

Treatment

Traditionally, liver damage from cirrhosis cannot be reversed, but treatment could stop or delay further progression and reduce complications. A healthy diet is encouraged, as cirrhosis may be an energy-consuming process. Close follow-up is often necessary. Antibiotics will be prescribed for infections, and various medications can help with itching. Laxatives, such as lactulose, decrease risk of constipation; their role in preventing encephalopathy is limited.

Treating underlying causes

Alcoholic cirrhosis caused by alcohol abuse is treated by abstaining from alcohol. Treatment for hepatitis-related cirrhosis involves medications used to treat the different types of hepatitis, such as interferon for viral hepatitis and corticosteroids for autoimmune hepatitis. Cirrhosis caused by Wilson's disease, in which copper builds up in organs, is treated with chelation therapy (e.g. penicillamine) to remove the copper.

Preventing further liver damage

Regardless of underlying cause of cirrhosis, alcohol and acetaminophen, as well as other potentially damaging substances, are discouraged. Vaccination of susceptible patients should be considered for Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B.

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

Varices

- Endoscopic screening in all cirrhotic patients

- If varices present--treat with propranolol or nadolol

Hepatocellular Cancer

- Incidence 1-6%/year in HCV-, HBV-, EtOH-related cirrhosis

- Screening frequency & benefit controversial

- Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) every 6 months (~60% sensitive, ~90% specific)

- Ultrasound every 6 months (~75% sensitive, ~90% specific)

Preventing complications

Ascites

Salt restriction is often necessary, as cirrhosis leads to accumulation of salt (sodium retention). Diuretics may be necessary to suppress ascites.

Esophageal variceal bleeding

For portal hypertension, propranolol is a commonly used agent to lower blood pressure over the portal system. In severe complications from portal hypertension, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is occasionally indicated to relieve pressure on the portal vein. As this can worsen encephalopathy, it is reserved for those at low risk of encephalopathy, and is generally regarded only as a bridge to liver transplantation or as a palliative measure.

Hepatic encephalopathy

High-protein food increases the nitrogen balance, and would theoretically increase encephalopathy; in the past, this was therefore eliminated as much as possible from the diet. Recent studies show that this assumption was incorrect, and high-protein foods are even encouraged to maintain adequate nutrition.

Hepatorenal syndrome

The hepatorenal syndrome is defined as a urine sodium less than 10 mmol/L and a serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl (or 24 hour creatinine clearance less than 40 ml/min) after a trial of volume expansion without diuretics.[7]

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Cirrhotic patients with ascites are at risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Transplantation

If complications cannot be controlled or when the liver ceases functioning, liver transplantation is necessary. Survival from liver transplantation has been improving over the 1990s, and the five-year survival rate is now around 80%, depending largely on the severity of disease and other medical problems in the recipient.[8] In the United States, the MELD score (online calculator)[9] is used to prioritize patients for transplantation. Transplantation necessitates the use of immune suppressants (ciclosporin or tacrolimus).

Decompensated cirrhosis

In patients with previously stable cirrhosis, decompensation may occur due to various causes, such as constipation, infection (of any source), increased alcohol intake, medication, bleeding from esophageal varices or dehydration. It may take the form of any of the complications of cirrhosis listed above.

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis generally require admission to hospital, with close monitoring of the fluid balance, mental status, and emphasis on adequate nutrition and medical treatment - often with diuretics, antibiotics, laxatives and/or enemas, thiamine and occasionally steroids, acetylcysteine and pentoxifylline. Administration of saline is generally avoided as it would add to the already high total body sodium content that typically occurs in cirrhosis.

Primary Prevention

- Education about hepatotoxins:

- EtOH

- Acetaminophen

- Herbals

- Maintenance of adequate caloric intake: 2000-3000 kcal/d

- Hepatitis A Virus vaccination, Pneumovax

Pathological Findings

-

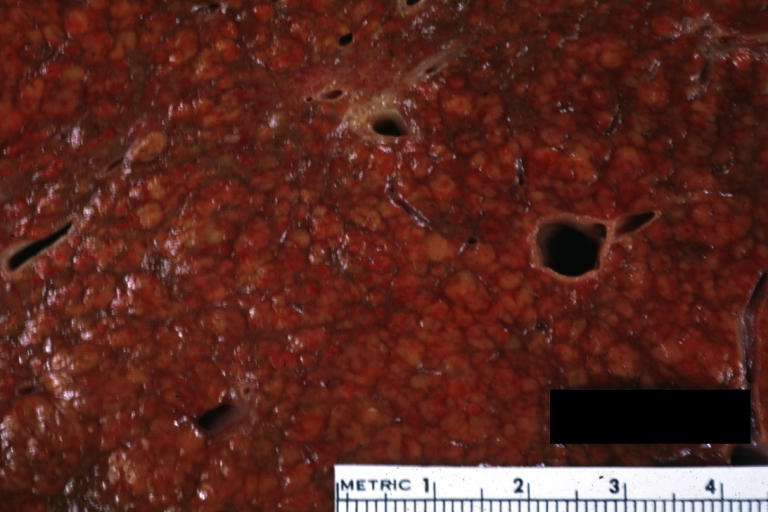

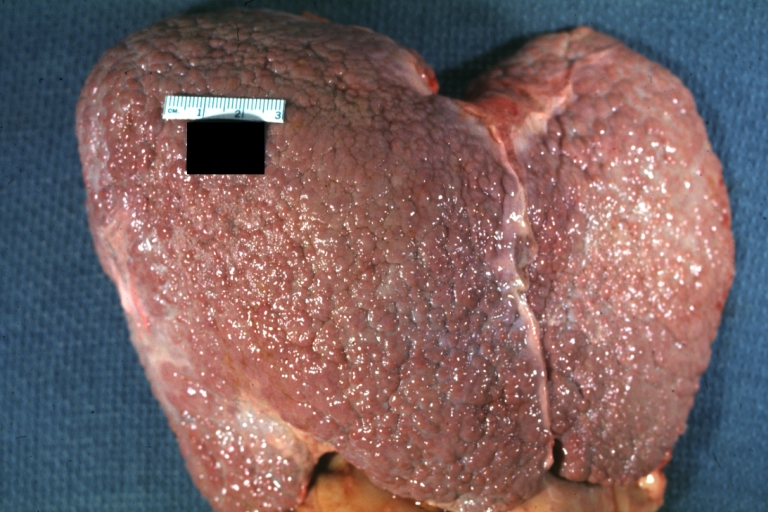

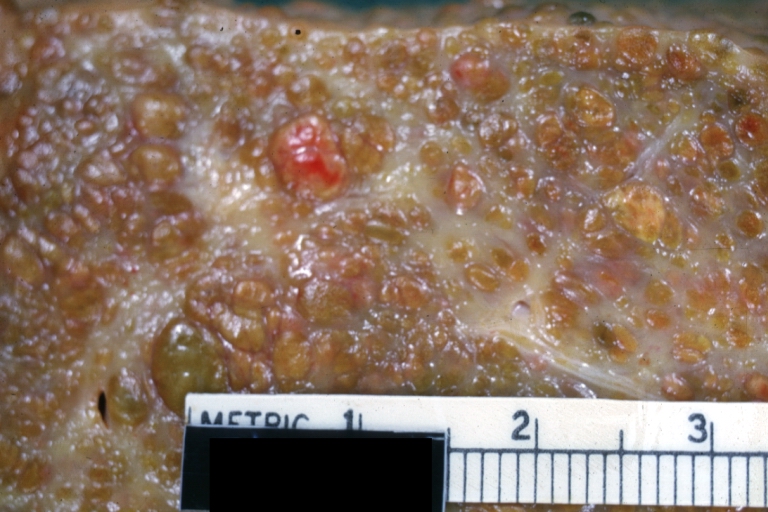

Cirrhosis: Gross, external view of micronodular cirrhosis

-

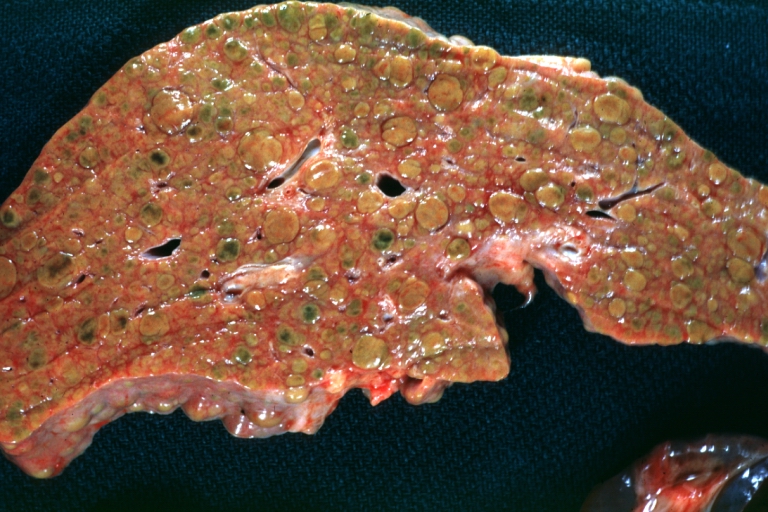

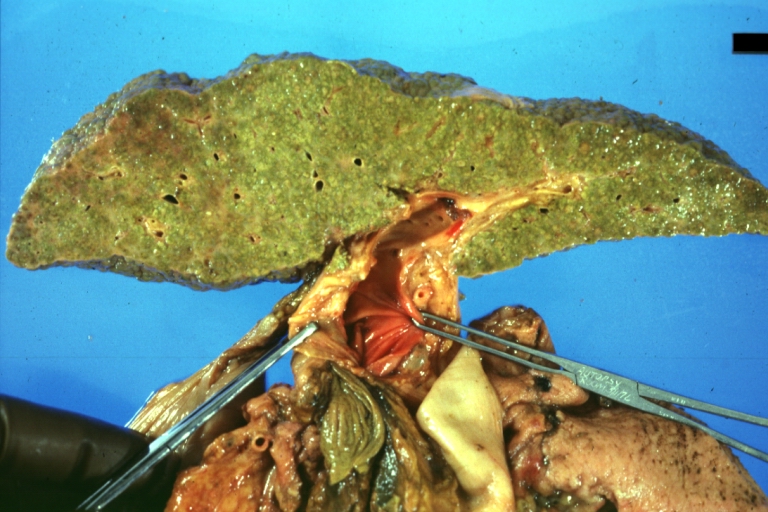

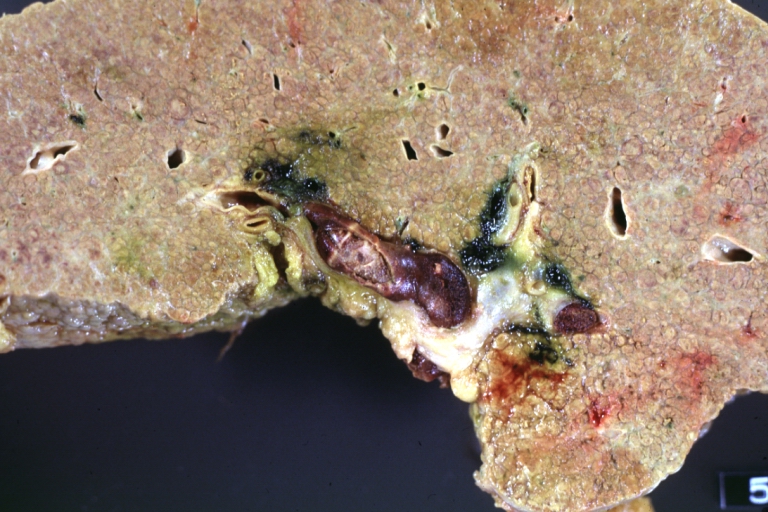

Cirrhosis: Gross, cut section of previous one (an excellent example)

-

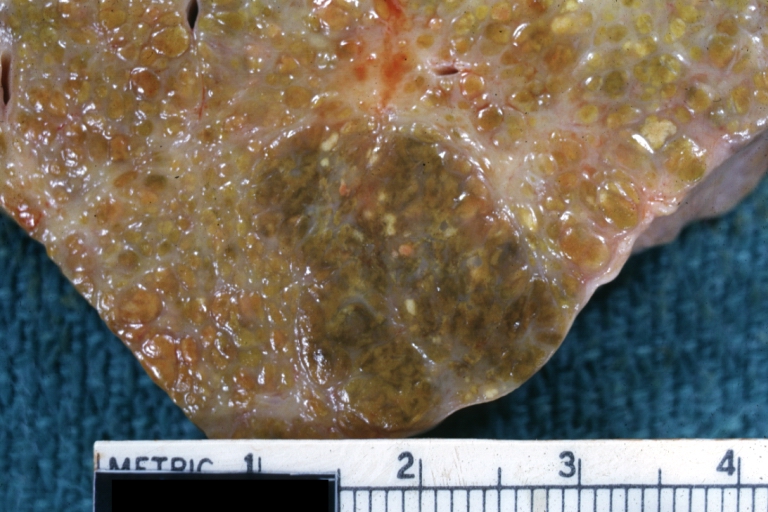

Cirrhosis: Gross, close-up image

-

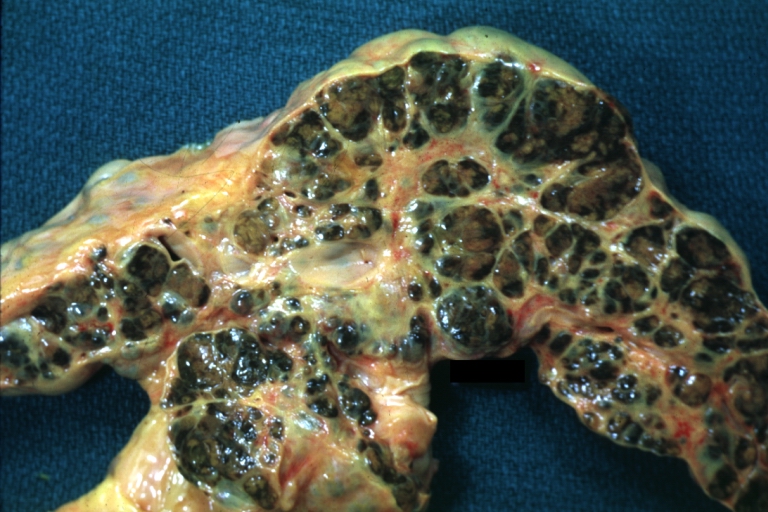

Macronodular cirrhosis and hepatoma

-

Cirrhosis: Gross, close-up, natural color (an excellent example)

-

Cirrhosis: Gross, close-up (an excellent example)

-

Cirrhosis: Gross, close-up view

-

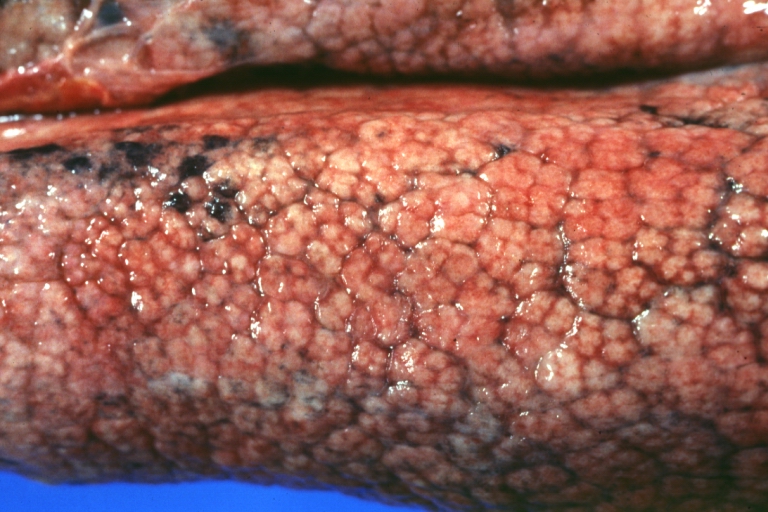

Micronodular cirrhosis: Gross, external view (an excellent example)

-

Micronodular cirrhosis: Gross, close-up image

-

Micronodular cirrhosis: Gross (an excellent example)

-

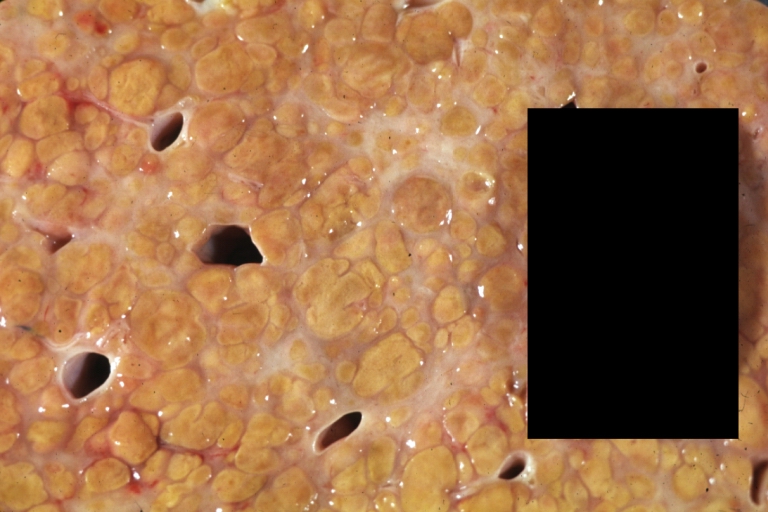

Macronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color (perfect color for cirrhosis), close-up, an excellent example

-

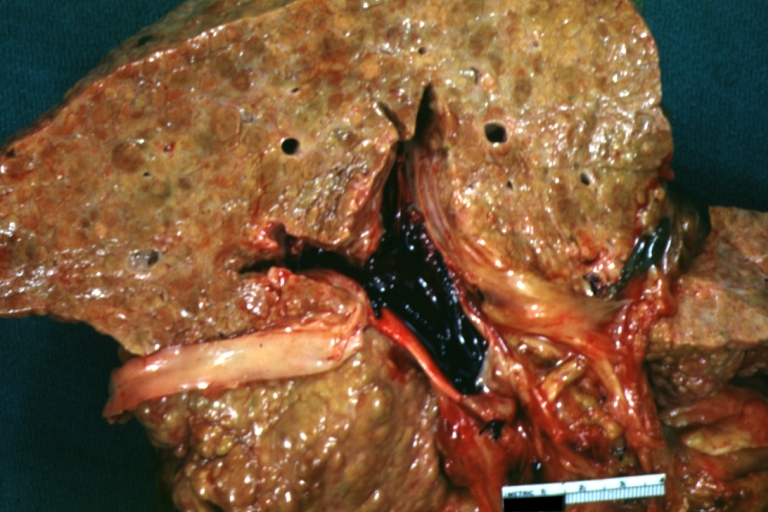

Cirrhosis with portocaval shunt: Gross, severe cirrhosis with extensive liver necrosis due to thrombosis of portocaval shunt (well shown)

-

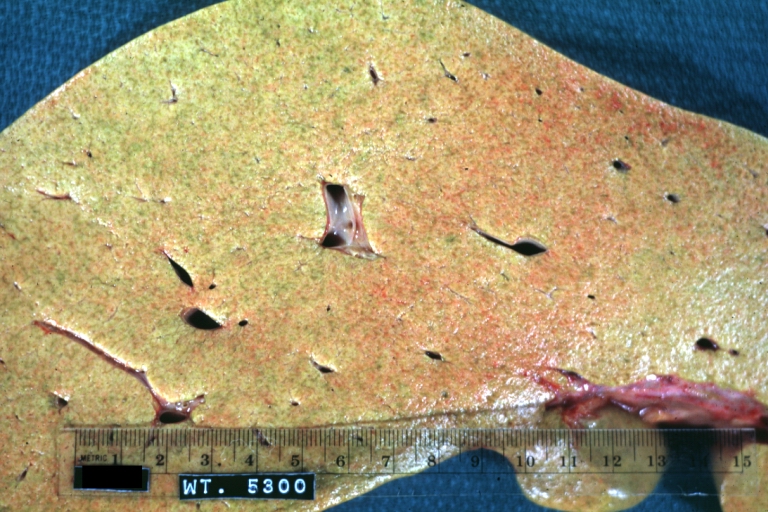

Endstage cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, close-up (an excellent example)

-

Endstage cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, close-up view is an excellent example for nodules of yellow-orange liver tissue and broad irregular bands of fibrosis

-

Endstage cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, close-up cut surface, very well shown nodules of yellow and necrotic opaque liver tissue with broad and irregular bands of fibrosis (an excellent example)

-

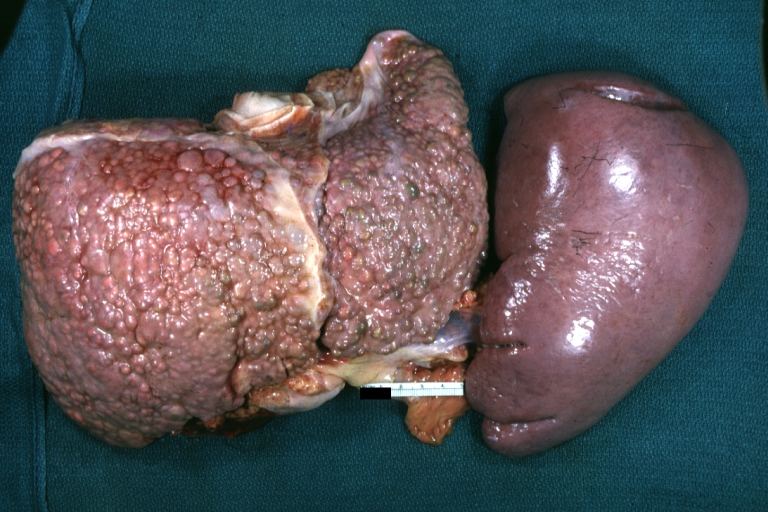

Macronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, external view of liver and very enlarged spleen (liver has variable size nodules up to about 2 cm)

-

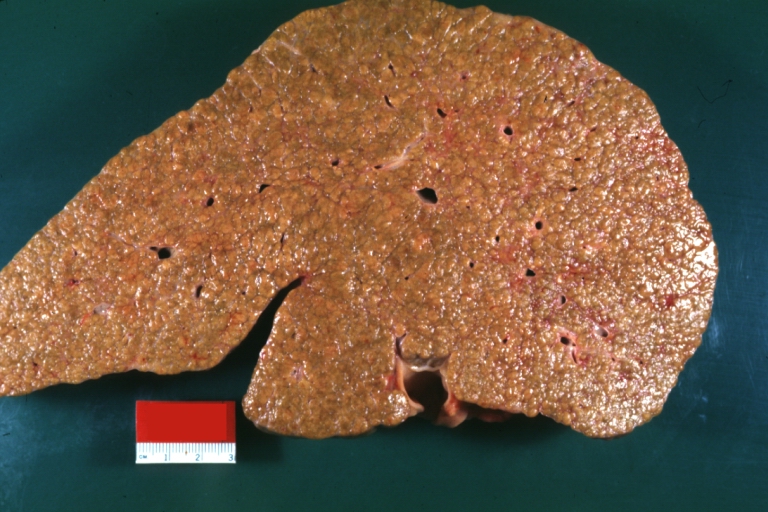

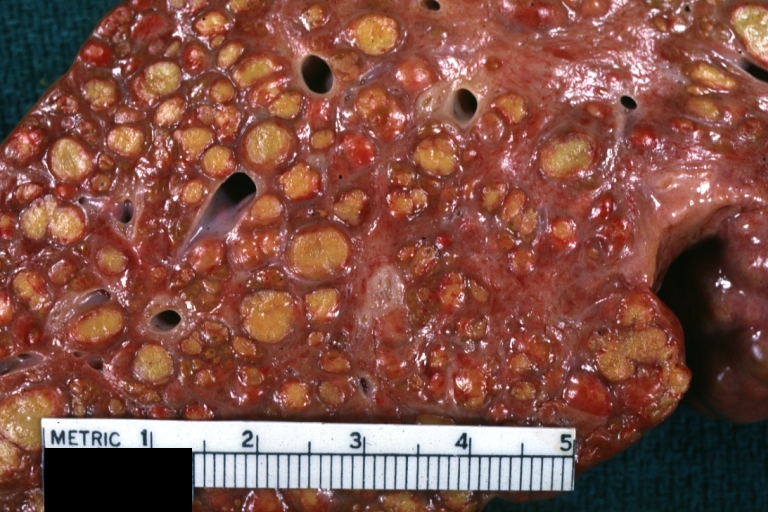

Macronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, cut surface, large irregular bands of fibrosis with variable size liver cell nodules up to about 8 mm and all necrotic appears to be an end stage liver disease.

-

Macronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color view of frontal sections of liver and spleen showing a contracted macronodular liver and an enlarged spleen as large as the liver

-

Macronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color slab of liver

-

Fatty change and early cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, rather close-up image showing typical fatty color, and in lighting at lower right of micrography micronodularity is evident (quite good example)

-

Cirrhosis with portal vein thrombosis: Gross, natural color, sectioned liver with portal vein exposed and filled with red thrombus. A good example of end stage cirrhosis.

-

Endstage cirrhosis with lobular necrosis: Gross, natural color, very close-up view (an excellent example of alcoholic cirrhosis)

-

Micronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color view of whole liver through capsule with obvious cirrhosis (note to quite large liver)

-

Micronodular cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, view of whole liver showing external surface typical cirrhotic liver (history of alcoholism)

-

Lung: Idiopathic Interstitial Fibrosis: Gross, natural color, an excellent photo of lung cirrhosis (close-up view)

-

Endstage cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, slice of liver. Portal vein is opened to show size and patency.

-

Endstage cirrhosis: Gross, natural color, severe cirrhosis with bile stasis

-

Portal Vein Thrombosis with cirrhosis: Gross, close-up, micronodular cirrhosis with portal vein thrombosis

-

Lung: Hematite: Gross, natural color, external view of "pulmonary cirrhosis" with typical hematite color

-

Gross, natural color of liver and stomach view from external surfaces, micronodular cirrhosis and hemorrhagic gastritis (as the surgeon would see these in natural color)

Mikroscopic Images

Chronic active hepatitis - Cirrhosis

{{#ev:youtube|CzKGvWZrUpU}}

Micronodular cirrhosis

{{#ev:youtube|CV8OYeIUXko}}

Primary biliary cirrhosis

{{#ev:youtube|Jj8ozr_IttM}}

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rodriguez-Roisin R, Krowka MJ, Herve P, Fallon MB; ERS Task Force Pulmonary-Hepatic Vascular Disorders (PHD) Scientific Committee. Pulmonary-Hepatic vascular Disorders (PHD). Eur Respir J 2004;24:861-80. PMID 15516683.

- ↑ Grant, A (1999). "Guidelines on the use of liver biopsy in clinical practice". Gut. 45 (Suppl 4): 1–11. PMID 10485854.

The main cause of mortality after percutaneous liver biopsy is intraperitoneal haemorrhage as shown in a retrospective Italian study of 68,000 percutaneous liver biopsies in which all six patients who died did so from intraperitoneal haemorrhage. Three of these patients had had a laparotomy, and all had either cirrhosis or malignant disease, both of which are risk factors for bleeding.

Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Li CP, Lee FY, Hwang SJ; et al. (1999). "Spider angiomas in patients with liver cirrhosis: role of alcoholism and impaired liver function". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 34 (5): 520–3. PMID 10423070.

- ↑ Foucher J, Chanteloup E, Vergniol J; et al. (2006). "Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study". Gut. 55 (3): 403–8. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.069153. PMID 16020491.

- ↑ Pathology atlas, "cirrhosis".

- ↑ Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646-9. PMID 4541913.

- ↑ Ginés P, Arroyo V, Quintero E; et al. (1987). "Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites. Results of a randomized study". Gastroenterology. 93 (2): 234–41. PMID 3297907.

- ↑ E-medicine liver transplant outlook and survival rates

- ↑ Cosby RL, Yee B, Schrier RW (1989). "New classification with prognostic value in cirrhotic patients". Mineral and electrolyte metabolism. 15 (5): 261–6. PMID 2682175.

External links

- Cirrhosis of the Liver at the National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC). NIH Publication No. 04-1134, December 2003.

- [4] at the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health. Medline Plus: Cirrhosis -- also called: Hepatic fibrosis

zh-min-nan:Koaⁿ-ngē-hoà da:Skrumplever de:Leberzirrhose eu:Zirrosi hr:Ciroza jetre is:Skorpulifur it:Cirrosi epatica he:שחמת הכבד la:Cirrosis iecuris ln:Bokɔnɔ bwa libale mk:Цироза nl:Levercirrose no:Skrumplever sq:Cirroza sl:Ciroza jeter fi:Kirroosi sv:Skrumplever