Congestive heart failure laboratory tests: Difference between revisions

(/* 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure/2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure/2009 ACC/AHA Focused Update and 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult (DO NOT EDIT) Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW, Antman EM, Smith SC Jr, Adams CD, And...) |

|||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

This ratio is measured during a [[Valsalva maneuver]]<ref name="pmid28754567">{{cite journal| author=Gilotra NA, Tedford RJ, Wittstein IS, Yenokyan G, Sharma K, Russell SD et al.| title=Usefulness of Pulse Amplitude Changes During the Valsalva Maneuver Measured Using Finger Photoplethysmography to Identify Elevated Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure in Patients With Heart Failure. | journal=Am J Cardiol | year= 2017 | volume= 120 | issue= 6 | pages= 966-972 | pmid=28754567 | doi=10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.06.029 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=28754567 }} </ref><ref name="pmid28185634">{{cite journal| author=Galiatsatos P, Win TT, Monti J, Johnston PV, Herzog W, Trost JC et al.| title=Usefulness of a Noninvasive Device to Identify Elevated Left Ventricular Filling Pressure Using Finger Photoplethysmography During a Valsalva Maneuver. | journal=Am J Cardiol | year= 2017 | volume= 119 | issue= 7 | pages= 1053-1060 | pmid=28185634 | doi=10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.063 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=28185634 }} </ref>. A device for measuring this has been patented<ref>Silber HA (2008). [https://patents.google.com/patent/US9549678B2/en Non-invasive methods and systems for assessing cardiac filling pressure]</ref>. | This ratio is measured during a [[Valsalva maneuver]]<ref name="pmid28754567">{{cite journal| author=Gilotra NA, Tedford RJ, Wittstein IS, Yenokyan G, Sharma K, Russell SD et al.| title=Usefulness of Pulse Amplitude Changes During the Valsalva Maneuver Measured Using Finger Photoplethysmography to Identify Elevated Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure in Patients With Heart Failure. | journal=Am J Cardiol | year= 2017 | volume= 120 | issue= 6 | pages= 966-972 | pmid=28754567 | doi=10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.06.029 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=28754567 }} </ref><ref name="pmid28185634">{{cite journal| author=Galiatsatos P, Win TT, Monti J, Johnston PV, Herzog W, Trost JC et al.| title=Usefulness of a Noninvasive Device to Identify Elevated Left Ventricular Filling Pressure Using Finger Photoplethysmography During a Valsalva Maneuver. | journal=Am J Cardiol | year= 2017 | volume= 119 | issue= 7 | pages= 1053-1060 | pmid=28185634 | doi=10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.063 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=28185634 }} </ref>. A device for measuring this has been patented<ref>Silber HA (2008). [https://patents.google.com/patent/US9549678B2/en Non-invasive methods and systems for assessing cardiac filling pressure]</ref>. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 14:27, 10 February 2022

| Resident Survival Guide |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Lakshmi Gopalakrishnan, M.B.B.S. [2]; Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [3]; Tarek Nafee, M.D. [4]

Overview

Once the diagnosis of heart failure is made, subsequent laboratory studies should be directed toward the identification of an underlying cause of heart failure.

Laboratory Tests

Renal Function

Renal function should be assessed as a rough guide to the patient's intravascular volume status and renal perfusion. A urinalysis is helpful in the assessment of the patient's volume status. Electrolyte assessment and the correction of electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia, hyperkalemia and hypomagnesemia is critical in those patients treated with diuretics. Hyponatremia (due to poor stimulation of the baroreceptors and appropriate ADH release and free water retention) is associated with a poor prognosis.

Hematologic Studies

A complete blood count should be obtained to assess for the presence of anemia which may exacerbate heart failure and to assess the patients coagulation status which may be impaired due to hepatic congestion.

Thyroid Studies

The assessment of thyroid function tests is particularly important in the patient who is being treated with concomitant therapy with an agent such as amiodarone.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers are going to play a great role in diagnosis of heart failure.

Natriuretic Peptides: BNP or NT-proBNP

BNP or its amino-terminal cleavage equivalent (NT-proBNP) is generated by cardiomyocytes in the context of numerous triggers, most notably myocardial stretch.

BNP levels may be useful in the initial establishment of the diagnosis of heart failure in the patient with dyspnea of unclear etiology. In a meta-analysis, BNP was superior N-terminal pro-BNP (NTproBNP) and was associated with a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 84% in the diagnosis of heart failure in the primary care setting.[1]

These biomarkers have been studied for the detection of elevated cardiac pressures[2][3][4], low ejection fraction[5], or both[6][7].

Clinical practice guidelines suggest their measurement is helpful for diagnosis or ruling out heart failure especially in acute setting.[8]

| Cardiac cause | Non cardiac causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated BNP |

|

|

| LowBNP |

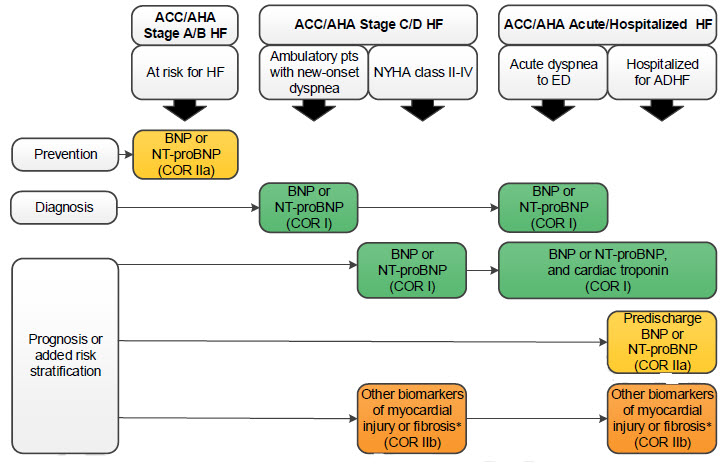

Biomarkers indications for use

Abbreviations:

ACC: American College of Cardiology, AHA: American Heart Association, ADHF: acute decompensated

heart failure, BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide, COR: Class of Recommendation, ED: emergency department, HF: heart failure, NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, NYHA: New York Heart Association, pts: patients

(*)Other biomarkers of injury or fibrosis include soluble ST2 receptor, galectin-3, and high-sensitivity troponin.

Biomarkers of Myocardial Injury: Cardiac Troponin T or I

Even without obvious myocardial ischemic injury, troponin level may be increased in heart failure which means undergoing myocyte injury.[11] Elevated levels of troponin is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive LV dysfunction and increased mortality rates.[12]

Carbohydrate Antigen 125

CA-125 is an emerging, highly sensitive biomarker for heart failure.[13] Although it is not yet used in clinical practice, the CHANCE-HF trial has demonstrated utility in using CA-125 to guide diuretic therapy and for determining short-term prognosis.[14] CA-125 is a non-specific antigen that is most strongly associated with ovarian cancer. In patients with acute heart failure, ambulatory follow-up care aimed at titrating diuretic use according to CA-125 levels has demonstrated ~50% reduction in rehospitalizations.[14] CA-125 was first associated with heart failure in 1999 by Nagele et al.[13][15]

Noninvasive assessment of pulse wave amplitude ratio

This ratio is measured during a Valsalva maneuver[16][17]. A device for measuring this has been patented[18].

References

- ↑ Ewald B, Ewald D, Thakkinstian A, Attia J (2008). "Meta-analysis of B type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro B natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of clinical heart failure and population screening for left ventricular systolic dysfunction". Intern Med J. 38 (2): 101–13. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01454.x. PMID 18290826.

- ↑ Dokainish H, Zoghbi WA, Lakkis NM, Al-Bakshy F, Dhir M, Quinones MA; et al. (2004). "Optimal noninvasive assessment of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparison of tissue Doppler echocardiography and B-type natriuretic peptide in patients with pulmonary artery catheters". Circulation. 109 (20): 2432–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000127882.58426.7A. PMID 15123522.

- ↑ Kelder JC, Cowie MR, McDonagh TA, Hardman SM, Grobbee DE, Cost B; et al. (2011). "Quantifying the added value of BNP in suspected heart failure in general practice: an individual patient data meta-analysis". Heart. 97 (12): 959–63. doi:10.1136/hrt.2010.220426. PMID 21478382.

- ↑ Dokainish H, Zoghbi WA, Lakkis NM, Quinones MA, Nagueh SF (2004). "Comparative accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide and tissue Doppler echocardiography in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure". Am J Cardiol. 93 (9): 1130–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.042. PMID 15110205.

- ↑ Groenning BA, Raymond I, Hildebrandt PR, Nilsson JC, Baumann M, Pedersen F (2004). "Diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of left ventricular systolic heart failure by plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide concentrations in a large sample of the general population". Heart. 90 (3): 297–303. PMC 1768111. PMID 14966052.

- ↑ Kuster GM, Tanner H, Printzen G, Suter TM, Mohacsi P, Hess OM (2002). "B-type natriuretic peptide for diagnosis and treatment of congestive heart failure". Swiss Med Wkly. 132 (43–44): 623–8. doi:2002/43/smw-10081 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 12587046. - ↑ Maisel AS, McCord J, Nowak RM, Hollander JE, Wu AH, Duc P; et al. (2003). "Bedside B-Type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Results from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study". J Am Coll Cardiol. 41 (11): 2010–7. PMID 12798574.

- ↑ Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL (2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62 (16): e147–239. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. PMID 23747642.

- ↑ Taylor JA, Christenson RH, Rao K, Jorge M, Gottlieb SS (2006). "B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide are depressed in obesity despite higher left ventricular end diastolic pressures". Am Heart J. 152 (6): 1071–6. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.07.010. PMID 17161055.

- ↑ Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA (2017). "Evidence Supporting the Existence of a Distinct Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction". Circulation. 136 (1): 6–19. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026807. PMC 5501170. PMID 28381470.

- ↑ Hudson MP, O'Connor CM, Gattis WA, Tasissa G, Hasselblad V, Holleman CM, Gaulden LH, Sedor F, Ohman EM (2004). "Implications of elevated cardiac troponin T in ambulatory patients with heart failure: a prospective analysis". Am. Heart J. 147 (3): 546–52. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.014. PMID 14999208.

- ↑ Horwich TB, Patel J, MacLellan WR, Fonarow GC (2003). "Cardiac troponin I is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality rates in advanced heart failure". Circulation. 108 (7): 833–8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000084543.79097.34. PMID 12912820.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 D'Aloia A, Vizzardi E, Metra M (2016). "Can Carbohydrate Antigen-125 Be a New Biomarker to Guide Heart Failure Treatment?: The CHANCE-HF Trial". JACC Heart Fail. 4 (11): 844–846. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.09.001. PMID 27810078.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Núñez J, Llàcer P, Bertomeu-González V, Bosch MJ, Merlos P, García-Blas S; et al. (2016). "Carbohydrate Antigen-125-Guided Therapy in Acute Heart Failure: CHANCE-HF: A Randomized Study". JACC Heart Fail. 4 (11): 833–843. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.06.007. PMID 27522630.

- ↑ Nägele H, Bahlo M, Klapdor R, Schaeperkoetter D, Rödiger W (1999). "CA 125 and its relation to cardiac function". Am Heart J. 137 (6): 1044–9. PMID 10347329.

- ↑ Gilotra NA, Tedford RJ, Wittstein IS, Yenokyan G, Sharma K, Russell SD; et al. (2017). "Usefulness of Pulse Amplitude Changes During the Valsalva Maneuver Measured Using Finger Photoplethysmography to Identify Elevated Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure in Patients With Heart Failure". Am J Cardiol. 120 (6): 966–972. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.06.029. PMID 28754567.

- ↑ Galiatsatos P, Win TT, Monti J, Johnston PV, Herzog W, Trost JC; et al. (2017). "Usefulness of a Noninvasive Device to Identify Elevated Left Ventricular Filling Pressure Using Finger Photoplethysmography During a Valsalva Maneuver". Am J Cardiol. 119 (7): 1053–1060. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.063. PMID 28185634.

- ↑ Silber HA (2008). Non-invasive methods and systems for assessing cardiac filling pressure