COVID-19-associated pneumonia: Difference between revisions

Sara Mohsin (talk | contribs) |

Sara Mohsin (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

* There is no established system for the classification of [[coronavirus]] infected pneumonia. Based on the detailed observation of case reports and case series, it has been found that COVID-19 patients differ in their presentation in the emergency department based upon the following three factors: | * There is no established system for the classification of [[coronavirus]] infected pneumonia. Based on the detailed observation of case reports and case series, it has been found that COVID-19 patients differ in their presentation in the emergency department based upon the following three factors: | ||

# The severity of infection, host [[immune response]], preserved physiological reserve and associated comorbidities. | # The severity of infection, host [[immune response]], preserved physiological reserve, and associated comorbidities. | ||

# Response of patient to the [[hypoxemia]] in terms of ventilator | # Response of patient to the [[hypoxemia]] in terms of ventilator | ||

# the time between the presentation of patient to the emergency department and the onset of the disease. | # the time between the presentation of patient to the emergency department and the onset of the disease. | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

* The H type pattern has been reported to present in 20-30 % patients in one case series. It usually fits the criteria of severe [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|ARDS]] or progresses rapidly towards [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|ARDS]]. | * The H type pattern has been reported to present in 20-30 % patients in one case series. It usually fits the criteria of severe [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|ARDS]] or progresses rapidly towards [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|ARDS]]. | ||

*In May 2020, it was postulated that there is also third distinctive | *In May 2020, it was postulated that there is also a third distinctive type. This phenotype usually mimics the patchy [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|ARDS]] phenotype. | ||

==Pathophysiology== | ==Pathophysiology== | ||

Revision as of 00:12, 12 July 2020

|

COVID-19 Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

COVID-19-associated pneumonia On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of COVID-19-associated pneumonia |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for COVID-19-associated pneumonia |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Usman Ali Akbar, M.B.B.S.[2]

Synonyms and keywords:2019 novel coronavirus disease, COVID19,Wuhan virus, L type COVID pneumonia, H type Pneumonia

Overview

The severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by SARS-CoV-2 is the cause of global pandemic that began in the Chinese city of Wuhan late 2019. In December 2019, a novel coronavirus was detected in pneumonia patients which were later named as 2019-nCoV. Pneumonia appears to be the most frequent manifestation of infection. COVID-19 pneumonia despite mimicking the symptoms and criteria according to Berlin definition of ARDS is a specific disease whose particular features are severe hypoxemia often associated with the normal or near-normal respiratory system compliance.

Historical Perspective

- In December 2019, there were case reports of a cluster of acute respiratory illness in the Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.

- In January 2020, novel coronavirus was identified in the samples of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from a patient in Wuhan.[1]

- Later this has been confirmed as the cause of novel corona virus-infected pneumonia.

- The first cases were reported by Huang et al in which most of the patients had a history of exposure to the seafood wholesale market.

- There have been no effective therapies or vaccines available for NCIP as of yet.

- In May 2020, it was postulated that there is also a third distinctive type. This phenotype usually mimics the patchy ARDS phenotype.

Classification

- There is no established system for the classification of coronavirus infected pneumonia. Based on the detailed observation of case reports and case series, it has been found that COVID-19 patients differ in their presentation in the emergency department based upon the following three factors:

- The severity of infection, host immune response, preserved physiological reserve, and associated comorbidities.

- Response of patient to the hypoxemia in terms of ventilator

- the time between the presentation of patient to the emergency department and the onset of the disease.

- Based on these three factors, NCIP has been divided COVID-19 associated pneumonia into the following two different phenotypes:

| COVID‑19 pneumonia, Type L | COVID‑19 pneumonia, Type H |

|---|---|

| Low elastance | High elastance |

| Low ventilation to perfusion ratio | High Left to right shunt |

| Low lung weight | High lung weight |

| Low lung recruitability. | High lung recruitability |

- The H type pattern has been reported to present in 20-30 % patients in one case series. It usually fits the criteria of severe ARDS or progresses rapidly towards ARDS.

- In May 2020, it was postulated that there is also a third distinctive type. This phenotype usually mimics the patchy ARDS phenotype.

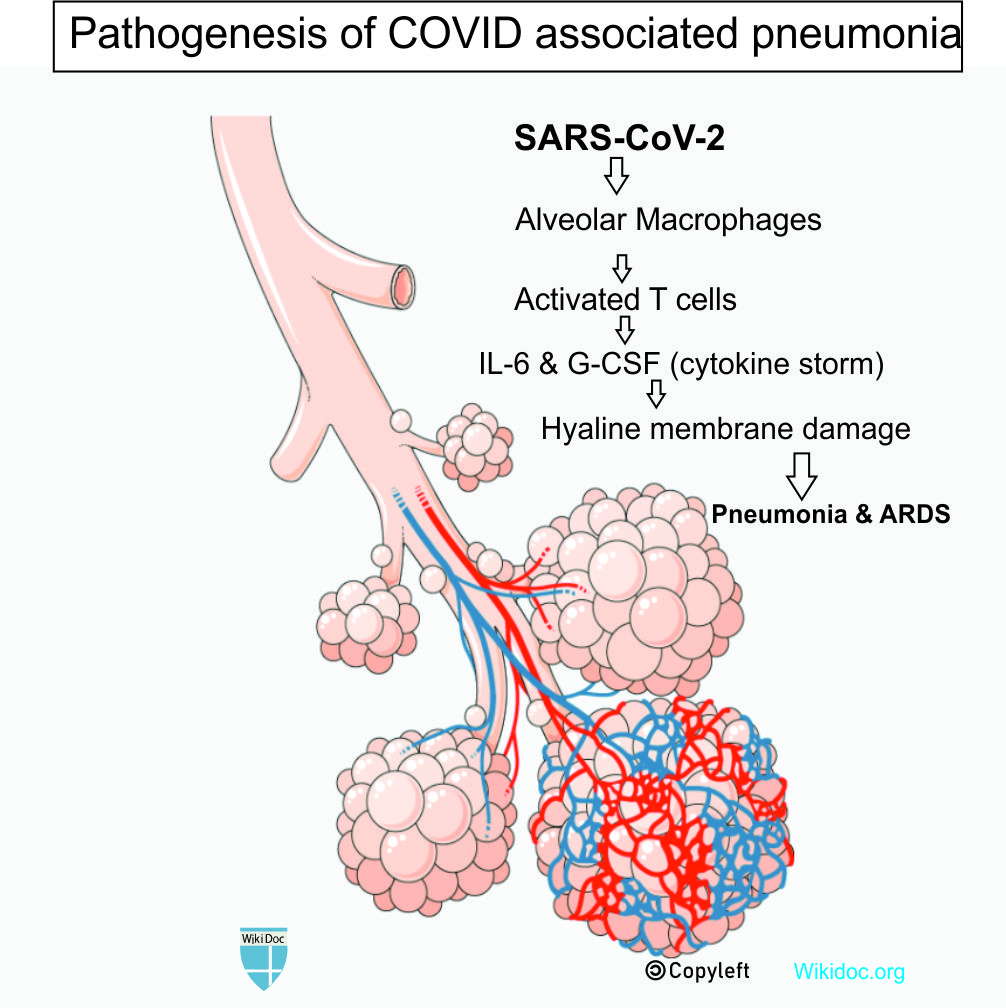

Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis behind COVID-19 associated pneumonia is not yet fully understood.

- COVID-19 usually express trans-membrane glycoproteins which are called "spike proteins" that allow the virus to attach itself to the target organ and enter into the cell

- Spike proteins bind to surface angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors.Specifically the RBD of the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 recognize ACE2 receptors.

- ACE2 is predominately expressed on type II pneumocytes. Other proteins such TMPRSS2 is also required for complete binding and transmissibility.

- TMPRSS2 cleaves the S protein and results into the fusion of the viral and host cell membrane.

- The virus replicates itself in the target cell using RNA dependent RNA polymerase.

- Lungs seems to be more vulnerable to the SARS-CoV-2 because of the large surface area.

- Direct lung injury leading to release of various cytokines such as (IL)–1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-12, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, interferon (IFN)–γ, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) initiates local inflammatory response and is responsible for the pulmonary manifestations of COVID-19.

- This leads to a modest local subpleural interstitial edema (ground glass lesions) at the interfaces between lung structures

- Vasoplegia results which further accounts for severe hypoxemia.

Differentiating COVID-19-associated pneumonia from other Diseases

- COVID-19 associated pneumonia can be classified from other viral pneumonia caused based on history of exposure to COVID-19, positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR, dyspnea, fever, cough,expectoration and uncommon associated findings like diarrhea, headache,vomiting and myalgias.

- Chest X-ray and other imaging modalities can further help us differentiate COVID-19 associated pneumonia from other causes.

- Chest X-ray usually shows bilateral, almost symmetrical areas of peripheral consolidation with perihilar infiltrates and an indistinct left heart border.

- CT-scan chest may show classical appearances of subpleural organizing areas of consolidation with patchy peripheral ground-glass opacities.

Epidemiology and Demographics

- In a study conducted in Spain, COVID-19 pneumonia was diagnosed in 32 (61.5%) patients, whereas the remaining 20 cases were categorized as URTI.

- In another study it was reported that the mean age of the population was 45 years, and 307 (79%) of 391 cases were adults aged 30–69 years. At the time of first clinical assessment, most cases were mild (102 [26%] of 391) or moderate (254 [65%] of 391), and only 35 (9%) were severe.

- The attack rate was reported to be more among females than male cases.[2]

Risk Factors

- The risk factors for COVID-19 associated pneumonia have not been properly established. Multiple studies show following factors to be the key to the progression of disease severity:[3]

- Diarrhea

- Lymphocyte count ≤ 1000 microlitre

- Ferritin ≥ 430 ng/ml

- CRP ≥ 2.5 mg/dL

- Consolidation on CT-scan chest

- Declining Neutrophil count

- COPD history

Screening

- There is an insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for COVID-19 associated pneumonia.

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

- Due to the evolution of pneumonia and high stress ventilation given as a part of treatment,type L COVID-19 pneumonia may progress to type H pneumonia over time.

- The key feature that regulate this transition is the depth of the negative inspiratory intrathoracic pressure that is associated with increased tidal volume in spontaneous breathing.

- This is based on experimental observation by Barach and Mascheroni. This has been termed as patient self inflicted lung injury. Over time the increased edema causes lung weight to increase.

- There is superimposed pressure and dependent atelectasis that develops over the progression of time.

- When the lung edema increases massively , lung's gas volume decreases and then tidal volumes that is usually generated for a given pressure also decreases.

- This leads to development of dyspnea and worsening of patient self inflicted lung injury.

Complications

- Pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 can further lead to following complications:

- Worsening hypoxemia[4]

- ARDS

- Barotrauma due to mechanical breathing support

- Acute cor-pulmonale

- Ventilator associated pneumonia

Prognosis

- Generally the progression of L Type pneumonia to the H type co-relates to poor prognosis as it further rapidly progresses to ARDS.

- A study reported development of ARDS in 20 percent patient with a median of eight days after the onset of symptoms.[1]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Study of Choice

- There is no established criteria for the diagnosis of COVID-19 associated pneumonia.

- Initial chest x-rays maybe normal.

- CT-scan chest is more sensitive than chest x-ray but there is no set criteria to diagnose COVID-19 associated pneumonia in COVID-19 patients.

History and Symptoms

- Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 can result into patients exhibiting following signs and symptoms:

- Most common signs and symptoms:

- Low to high-grade fever (98.6%)

- Generalized fatigue (69.6%)

- Non-productive/dry cough (59.4%)

- Myalgias (34.8%)

- Dyspnea (31.2%)

- Sore throat

- Rhinorrhea

- Other less common signs and symptoms:

- Most common signs and symptoms:

| Mild Illness | Moderate Pneumonia | Severe Pneumonia |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

Physical Examination

- Common physical examination findings include the following:

- Fever (most common)

- Respiratory rate >24 breaths/minute (almost all patients)

- Pulse rate >100 beats/min.

- Audible crackles (on chest examination)

- Signs of consolidation can be present in as early signs of pneumonia in COVID-19 patients such as:

- Decreased or bronchial breath sounds

- Dullness to percussion

- Tactile fremitus

- Egophony

Laboratory Findings

- Common laboratory findings among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 include:

- Lymphopenia (lymphocyte count, 0.8 × 109/L [interquartile range {IQR}, 0.6-1.1])

- Elevated aminotransaminase levels

- Elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels

- Elevated ferritin

- Elevated CRP

- Elevated ESR

- Elevated procalcitonin levels in those requiring ICU care

Electrocardiogram

- There are no specific ECG findings associated with COVID-19 associated pneumonia.

X-ray

- Chest radiograph may show bilateral, almost symmetrical areas of peripheral consolidation with perihilar infiltrates. In an endemic area, these appearances are highly suggestive of infection with COVID-19.

- The primary findings of COVID-19 are those of atypical or organizing pneumonia.[5]

- Almost 18 % of the patients can have normal chest x-ray findings early in the disease course but only 3% in severe disease.[6]

- Bilateral and/or multilobar involvement is common.

- CXR typically shows patchy or diffuse asymmetric airspace opacities which is also seen in other coronaviruses cases.[7]

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

- There are no specific echocardiography/ultrasound findings associated with COVID-19 associated pneumonia.

CT scan

- CT-scan chest findings in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia may show following abnormalities:[8]

- Ground-glass opacities

- Crazy paving appearance

- Air space consolidation

- Bronchovascular thickening in the lesion

- Traction bronchiectasis

Other Diagnostic Studies

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- Bronchoalveolar lavage may not be useful in diagnosing COVID-19 pneumonia, however various case reports suggest a collection of BAL fluid when consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs are negative to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of COVID-19-associated pneumonia.[9]

Treatment

Medical Therapy

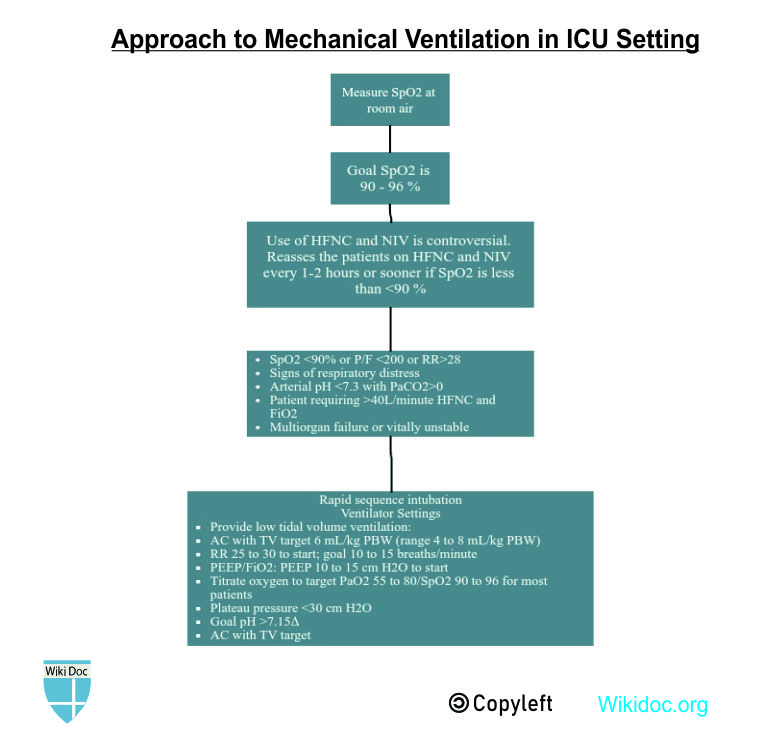

- The mainstay of treatment for COVID-19 associated pneumonia is supportive care and mechanical respiratory support.

- For suspected bacterial co-infection which may depict as elevated WBC, positive sputum culture, positive urinary antigen and atypical chest imaging, administer empiric coverage for community-acquired or health-care associated pneumonia.

- As there have been 3 distinct phenotypes of COVID-19 pneumonia, so there have been different treatment modalities for each of them.

- The first step is to reverse hypoxemia which can be done through increase in FiO2. This is well tolerated in patients with Type L pneumonia.

- For L Type with dyspnea, following different non-invasive options are available:

- High flow nasal cannula (HFNC)

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

- Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

- Esophageal manometry pressure is measured to prevent swings of central venous pressure.

- P0.1 and Pocclusion should be measured in intubated patient.

- Mechanical Ventilation should be instituted at the appropriate time.

Prevention

Primary Prevention

- The best way to prevent being infected by COVID-19 is to avoid being exposed to this virus by adopting the following practices for infection control:

- Often wash hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- Use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer containing at least 60% alcohol in case soap and water are not available.

- Avoid touching the eyes, nose, and mouth without washing hands.

- Avoid being in close contact with people sick with COVID-19 infection.

- Stay home while being symptomatic to prevent spread to others.

- Cover mouth while coughing or sneezing with a tissue paper, and then throw the tissue in the trash.

- Clean and disinfect the objects and surfaces which are touched frequently.

- There is currently no vaccine available to prevent COVID-19.

Secondary Prevention

- The secondary prevention measures of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) constitute protective measures to make sure that an infected individual does not transfer the disease to others by maintaining self-isolation at home or designated quarantine facilities.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wang, Dawei; Hu, Bo; Hu, Chang; Zhu, Fangfang; Liu, Xing; Zhang, Jing; Wang, Binbin; Xiang, Hui; Cheng, Zhenshun; Xiong, Yong; Zhao, Yan; Li, Yirong; Wang, Xinghuan; Peng, Zhiyong (2020-03-17). "Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China". JAMA. American Medical Association (AMA). 323 (11): 1061. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ↑ Bi, Qifang; Wu, Yongsheng; Mei, Shujiang; Ye, Chenfei; Zou, Xuan; Zhang, Zhen; Liu, Xiaojian; Wei, Lan; Truelove, Shaun A; Zhang, Tong; Gao, Wei; Cheng, Cong; Tang, Xiujuan; Wu, Xiaoliang; Wu, Yu; Sun, Binbin; Huang, Suli; Sun, Yu; Zhang, Juncen; Ma, Ting; Lessler, Justin; Feng, Tiejian (2020). "Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Elsevier BV. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30287-5. ISSN 1473-3099.

- ↑ Wang, Chang‐Zheng; Hu, Shun‐Lin; Wang, Lin; Li, Min; Li, Huan‐Tian (2020-05-29). "Early risk factors of the exacerbation of Coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia". Journal of Medical Virology. Wiley. doi:10.1002/jmv.26071. ISSN 0146-6615.

- ↑ Gattinoni, Luciano; Chiumello, Davide; Caironi, Pietro; Busana, Mattia; Romitti, Federica; Brazzi, Luca; Camporota, Luigi (2020-04-14). "COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes?". Intensive Care Medicine. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 46 (6): 1099–1102. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. ISSN 0342-4642.

- ↑ Rodrigues, J.C.L.; Hare, S.S.; Edey, A.; Devaraj, A.; Jacob, J.; Johnstone, A.; McStay, R.; Nair, A.; Robinson, G. (2020). "An update on COVID-19 for the radiologist - A British society of Thoracic Imaging statement". Clinical Radiology. Elsevier BV. 75 (5): 323–325. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.03.003. ISSN 0009-9260.

- ↑ Guan, Wei-jie; Ni, Zheng-yi; Hu, Yu; Liang, Wen-hua; Ou, Chun-quan; He, Jian-xing; Liu, Lei; Shan, Hong; Lei, Chun-liang; Hui, David S.C.; Du, Bin; Li, Lan-juan; Zeng, Guang; Yuen, Kwok-Yung; Chen, Ru-chong; Tang, Chun-li; Wang, Tao; Chen, Ping-yan; Xiang, Jie; Li, Shi-yue; Wang, Jin-lin; Liang, Zi-jing; Peng, Yi-xiang; Wei, Li; Liu, Yong; Hu, Ya-hua; Peng, Peng; Wang, Jian-ming; Liu, Ji-yang; Chen, Zhong; Li, Gang; Zheng, Zhi-jian; Qiu, Shao-qin; Luo, Jie; Ye, Chang-jiang; Zhu, Shao-yong; Zhong, Nan-shan (2020-04-30). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 382 (18): 1708–1720. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002032. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Chen, Simiao; Yang, Juntao; Yang, Weizhong; Wang, Chen; Bärnighausen, Till (2020). "COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year". The Lancet. Elsevier BV. 395 (10226): 764–766. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30421-9. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Bai, Harrison X.; Hsieh, Ben; Xiong, Zeng; Halsey, Kasey; Choi, Ji Whae; Tran, Thi My Linh; Pan, Ian; Shi, Lin-Bo; Wang, Dong-Cui; Mei, Ji; Jiang, Xiao-Long; Zeng, Qiu-Hua; Egglin, Thomas K.; Hu, Ping-Feng; Agarwal, Saurabh; Xie, Fangfang; Li, Sha; Healey, Terrance; Atalay, Michael K.; Liao, Wei-Hua (2020-03-10). "Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT". Radiology. Radiological Society of North America (RSNA): 200823. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020200823. ISSN 0033-8419.

- ↑ Gualano, Gina; Musso, Maria; Mosti, Silvia; Mencarini, Paola; Mastrobattista, Annelisa; Pareo, Carlo; Zaccarelli, Mauro; Migliorisi, Paolo; Vittozzi, Pietro; Zumla, Alimudin; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Palmieri, Fabrizio (2020). "Usefulness of bronchoalveolar lavage in the management of patients presenting with lung infiltrates and suspect COVID-19-associated pneumonia: A case report". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier BV. 97: 174–176. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.027. ISSN 1201-9712.