Olanzepine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 21–54 hours |

| Excretion | ? |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

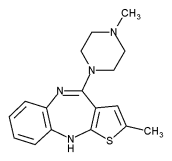

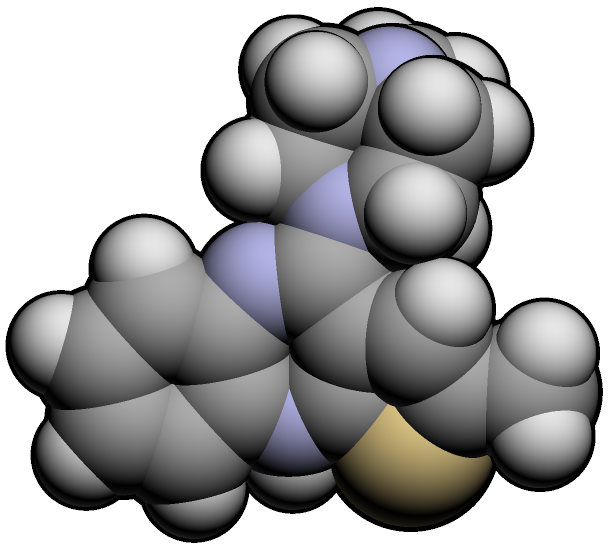

| Formula | C17H20N4S |

| Molar mass | 312.439 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [4]

Olanzapine (Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Zalasta, Zolafren, Olzapin, or in combination with fluoxetine Symbyax) is an atypical antipsychotic, approved by the FDA for the treatment of: schizophrenia on 1996-09-30 [1]; depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder, as part of the Symbyax formulation, on 2003-12-24[2]; acute manic episodes and maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder on 2004-01-14[3]. Off-label uses are listed below.

The olanzapine formulations are manufactured and marketed by the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and Company, whose patent for olanzapine proper expires in 2011.

Pharmacology

Olanzapine is structurally similar to clozapine, and is classified as a thienobenzodiazepine. Olanzapine has a higher affinity for 5-HT2 serotonin receptors than D2 dopamine receptors.

Like most atypical antipsychotics, compared to the older typical ones, olanzapine has a lower affinity for histamine, cholinergic muscarinic and alpha adrenergic receptors. The mode of action of olanzapine's antipsychotic activity is unknown. It may involve antagonism at serotonin receptors. Antagonism of dopamine receptors is associated with extrapyramidal effects such as tardive dyskinesia, and with therapeutic effects. Antagonizing H1 histamine receptors causes sedation and may cause weight gain, although antagonistic actions at 5-HT2C receptors have also been implicated in weight gain.

Dosing and administration

Olanzapine is available as a tablet in strengths of 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg and 20 mg and orally disintegrating wafers (known as Zydis), which dissolve on the tongue, in strengths of 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg and 20 mg. It is also available as a rapid-acting intramuscular injection for short-term acute use.

Dose may be adjusted depending on the person's response to the drug. The dose also will depend on certain medical problems the person may have. It is generally recommended to be taken once daily before bed as it is highly sedating.

Pharmacokinetics

Olanzapine displays linear kinetics. Its elimination half-life ranges from 21 to 54 hours. Steady state plasma concentrations are achieved in about a week. Olanzapine undergoes extensive first pass metabolism and bioavailability is not affected by food.

In cases of acute agitiation, olanzapine can also be administered by intramuscular injection in doses up to 10 milligrams. Olanzapine injection should not be given by the intravenous route, and should not be co-administered with benzodiazepines.

Metabolism

Olanzapine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system isoenzymes 1A2 and 2D6 (minor pathway). Drug metabolism may be increased or decreased by agents that induce (e.g. cigarette smoke) or inhibit (e.g. fluvoxamine or ciprofloxacin) CYP1A2 activity respectively.

Side effects

As with all neuroleptic drugs, olanzapine can cause tardive dyskinesia and rare, but life-threatening, neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Other recognised side effects may include:

- akathisia inability to remain still

- dry mouth

- dizziness

- sedation

- insomnia

- orthostatic hypotension

- weight gain (90% of users experience weight gain) (see below)

- increased appetite

- runny nose

- low blood pressure

- impaired judgment, thinking, and motor skills

- impaired spatial orientation

- impaired responses to senses

- seizure

- trouble swallowing

- dental problems and discoloration of teeth

- missed periods

- problems with keeping body temperature regulated

- apathy, lack of emotion

Weight gain

Of the atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine and clozapine are the most likely to induce weight gain.[4] The effect is more pronounced if high doses of olanzapine are used.[5] Smaller amounts of weight gain are induced by risperidone and quetiapine. Ziprasidone and aripiprazole are considered to be weight neutral antipsychotics.

Recently the Food and Drug Administration required the manufacturers of all atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes with these drugs. These effects may be related to the drugs' ability to induce weight gain, although there are some reports of metabolic changes in the absence of weight gain, and recent (2007) evidence suggests that olanzapine may directly affect adipocyte function, promoting fat deposition. There are some case reports of olanzapine-induced diabetic ketoacidosis.[6] There are data that suggest that olanzapine can decrease insulin sensitivity.[7], though there are other studies that seem to refute this[8]

Triglyceride levels rose from 99 to 166 in one year with olanzapine, in the CAFE ("Comparison of Atypicals for First-Episode Psychosis") study.[citation needed] Of the three drugs administered in that study, "olanzapine was associated with the greatest increases in body weight and related measures."[9] In the same study, where the median patient age was 23, 46% of male patients on Zyprexa had a waist size of 40" or greater after one year,[citation needed] and "80% gained 7% or more over their baseline weight compared with 57.6% of those receiving risperidone and 50% of those receiving quetiapine."[10] Impaired glucose metabolism, high triglycerides, and obesity have been shown to be constituents of the metabolic syndrome and may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The results of a large, random-design study funded by NIH's National Institute of Mental Health were published in September 2005. The 18-month study, which involved 1,400 participants at 57 sites around the country, found that "patients on olanzapine also experienced substantially more weight gain and metabolic changes associated with an increased risk of diabetes than those participants taking the other drugs."[11] However, the study also found that olanzapine helped more patients control symptoms for significantly longer than the other drugs. Specifically, after 18 months, the researchers found, "64 percent of the patients taking olanzapine had stopped, while at least 74 percent had quit each of the other medications."[12]

Data from a small, open-label, non-randomized study seem to suggest that taking olanzapine by orally dissolving tablets may not be associated with the same degree of weight gain as conventional tablet formulations;[13] however this has not been substantiated in a blinded experimental setting.

Off-label uses

Case-reports, open-label, and small pilot studies suggest efficacy of olanzapine for the treatment of some anxiety spectrum disorders (e.g. generalized anxiety disorder,[14] panic disorder,[15] post-traumatic stress disorder[16]); however, olanzapine has not been rigorously evaluated in randomized, placebo-controlled trials for this use and is not FDA approved for these indications. Other common off-label uses of olanzapine include the treatment of eating disorders (e.g. anorexia nervosa) and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder without psychotic features. It has also been used for Tourette's syndrome and stuttering.

Olanzapine has been marketed for dementia by Eli Lilly though it has never been shown to help with the symptoms of dementia. According to internal documents obtained by the New York Times, Lilly instructed its sales representatives to suggest that physicians prescribe Zyprexa to older patients with symptoms of dementia. One such document states "dementia should be first message" for primary care doctors, since they "do not treat bipolar" or schizophrenia, but "do treat dementia". Three months after its launch, Lilly's Zyprexa campaign, called "Viva Zyprexa", led to 49,000 new prescriptions. In 2002, the company changed the name of the primary care campaign to "Zyprexa Limitless" and began to focus on people with mild bipolar disorder who had previously been diagnosed as depressed, despite the fact that Zyprexa has been FDA approved only for the treatment of mania in bipolar disorder, not depression.[17]

Use in elderly

Citing an increased risk of stroke, in 2004 the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM) in the UK issued a warning that olanzapine and risperidone, both atypical antipsychotic medications, should not be given to elderly patients with dementia. In the U.S., olanzapine comes with a black box warning for increased risk of death in elderly patients. It is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis.[18]

Overdose

Symptoms of an overdose include tachycardia, agitation, dysarthria, decreased consciousness and coma. Death has been reported after an acute overdose of 450 mg, but also survival after an acute overdose of 1500 mg.[19] There is no specific, known antidote for olanzapine overdose, and even physicians are recommended to call a certified poison control center for information on the treatment of such a case.[19]

PRIME

The Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education (PRIME) study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Eli Lilly, tested the hypothesis that olanzapine might prevent the onset of psychosis in people at very high risk for schizophrenia. The study examined 60 patients with prodromal schizophrenia, who were at an estimated risk of 36–54% of developing schizophrenia within a year, and treated half with olanzapine and half with placebo.[20]

In this study, patients receiving olanzapine had a lower risk of progressing to psychosis, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Olanzapine was effective for treating the prodromal symptoms, but was associated with significant weight gain.[21]

Legal

According to a New York Times article published on December 17 2006,[22] Eli Lilly has engaged in a decade-long effort to play down the health risks of Zyprexa, its best-selling medication for schizophrenia, according to hundreds of internal Lilly documents and e-mail messages among top company managers. These documents and e-mail messages were soon made publicly available as a location hidden Tor service[23], and then made available on the public Internet. Eli Lilly got a temporary restraining order from a US District Court signed on January 4 2007 to stop the dissemination or downloading of Eli Lilly documents about Zyprexa, and this allowed them to get a few US-based websites to remove them; on January 8 2007, Judge Jack B. Weinstein refused the Electronic Frontier Foundation's motion to stay his order[24]. The documents can now only be downloaded from public Internet sites outside the US.[25][26][27]These health risks include an increased risk for diabetes through Zyprexa's links to obesity and its tendency to raise blood sugar. Zyprexa is Lilly’s top-selling drug, with sales of $4.2 billion last year.

The documents, given to The New York Times by Jim Gottstein, a lawyer representing mentally ill patients, show that Lilly executives kept important information from doctors about Zyprexa’s links to obesity and its tendency to raise blood sugar — both known risk factors for diabetes. The Times of London also obtained copies of the documents and reported that as early as October 1998, Lilly considered the risk of drug-induced obesity to be a "top threat" to Zyprexa sales.[28] In another document, dated October 9 2000, senior Lilly research physician Robert Baker noted that an academic advisory board he belonged to was "quite impressed by the magnitude of weight gain on olanzapine and implications for glucose."

Lilly’s own published data, which it told its sales representatives to play down in conversations with doctors, has shown that 30 percent of patients taking Zyprexa gain 22 pounds or more after a year on the drug, another study showed 16% of Zyprexa patients gained at least 30kg (66 pounds) in one year, and some patients have reported gaining 100 pounds or more. But Lilly was concerned that Zyprexa’s sales would be hurt if the company was more forthright about the fact that the drug might cause unmanageable weight gain or diabetes, according to the documents, which cover the period 1995 to 2004. In 2006, Lilly paid $700 million to settle 8,000 lawsuits from people who said they had developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa. Thousands more suits are still pending.[29]

In 2002, British and Japanese regulatory agencies warned that Zyprexa may be linked to diabetes, but even after the FDA issued a similar warning in 2003, Lilly did not publicly disclose their own findings.

Eli Lilly agreed on January 4 2007 to pay up to $500 million to settle 18,000 lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa. Including earlier settlements over Zyprexa, Lilly has now agreed to pay at least $1.2 billion to 28,500 people who claim they were injured by the drug. At least 1,200 suits are still pending, the company said. About 20 million people worldwide have taken Zyprexa since its introduction in 1996.[30]

See also

Note and References

- ↑

"Electronic Orange Book". Food and Drug Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-24. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑

"NDA 21-520" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2003-12-24. Retrieved 2007-10-31. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑

"NDA 20-592 / S-019" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2004-01-14. Retrieved 2007-10-31. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA. (1999) Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities. Journal of Clinical Psychology 60 358-63

- ↑ Green B (1999) Focus on olanzapine Current Med Res Opin 15 79-85

- ↑ Fulbright, April R. (2006). "Complete Resolution of Olanzapine-Induced Diabetic Ketoacidosis" (abstract). Journal of Pharmacy Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. 19 (4): 255–258. doi:10.1177/0897190006294180. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Olanzapine has been associated with diabetic ketoacidosis and also with weight gain, lipid abnormalities, and the development of type 2 diabetes.

- ↑ Sacher J; et al. (2007-08-22). Neuropshchopharmacology. Check date values in:

|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Sowell, Margaret (August 8 2003). "Evaluation of Insulin Sensitivity in Healthy Volunteers Treated with Olanzapine, Risperidone, or Placebo: A Prospective, Randomized Study Using the Two-Step Hyperinsulinemic, Euglycemic Clamp". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. The Endocrine Society. 88 (12): 5875–5880. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

In summary, this study did not demonstrate significant changes in insulin sensitivity in healthy subjects after 3 wk of treatment with olanzapine or risperidone.

Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (04 April 2006). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Olanzapine, Quetiapine and Risperidone in the Treatment of First Episode Psychosis: A Randomized Double Blind 52 Week Comparison". AstraZeneca Clinical Trials. AstraZeneca PLC. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

At week 12, the olanzapine-treated group had more weight gain, a higher increase in [ body mass index ], and a higher proportion of patients with a BMI increase of at least 1 unit compared with the quetiapine and risperidone groups (p<=0.01).

Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Moyer, Paula (2005-10-25). "CAFE Study Shows Varying Benefits Among Atypical Antipsychotics". Medscape Medical News. WebMD. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "NIMH study to guide treatment choices for schizophrenia" (Press release). National Institute of Mental Health. 19 September 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-18. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Carey, Benedict (September 20, 2005). "Little Difference Found in Schizophrenia Drugs". New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ de Haan L, van Amelsvoort T, Rosien K, Linszen D (2004). "Weight loss after switching from conventional olanzapine tablets to orally disintegrating olanzapine tablets". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 175 (3): 389–90. PMID 15322727.

- ↑ Pollack MH, Simon NM, Zalta AK, Worthington JJ, Hoge EA, Mick E, Kinrys G, Oppenheimer J. (2006). "Olanzapine augmentation of fluoxetine for refractory generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo controlled study". Biol Psychiatry. 59 (3): 211–5. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.005. PMID 16139813.

- ↑ Sepede G, De Berardis D, Gambi F, Campanella D, La Rovere R, D'Amico M, Cicconetti A, Penna L, Peca S, Carano A, Mancini E, Salerno RM, Ferro FM. (2003). "Olanzapine augmentation in treatment-resistant panic disorder: a 12-week, fixed-dose, open-label trial". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 107 (5): 394–6. PMID 16415705.

- ↑ Jakovljević M, Sagud M, Mihaljević-Peles A. (2006). "Olanzapine in the treatment-resistant, combat-related PTSD--a series of case reports". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 26 (1): 45–9. PMID 12752037.

- ↑ Berenson, Alex (Dec 18, 2006). "Drug Files Show Maker Promoted Unapproved Use". New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Important Safety Information for Olanzapine". Zyprexa package insert. Eli Lilly & Company. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. [...] ZYPREXA® (olanzapine) is not approved for the treatment of elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Symbyax (Olanzapine and fluoxetine) drug overdose and contraindication information". RxList: The Internet Drug Index. WebMD. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ McGlashan, T.H. (1 May 2003). "The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. I. Study rationale and design". Schizophrenia Research. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 61 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00439-5. PMID 12648731. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ McGlashan, Thomas H. (2006). "Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis". American Journal of Psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 163 (5): 790–99. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.790. PMID 16648318. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ [http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/17/business/17drug.html The New York Times December 17 2006

- ↑ The Zyprexa Memos (Requires Tor)

- ↑ Press Releases: January, 2007 | Electronic Frontier Foundation

- ↑ ZyprexaKills: Download the documents and memos as multi-page tiff files

- ↑ Canadian journalist Rob Wipond: Download the documents and memos as multi-page tiff files

- ↑ Swiss/German web site Boocompany.com: Download or browse the documents and memos as pdf files and OCR-generated searchable ASCII text files

- ↑ [1] Eli Lilly was Concerned by Zyprexa Side-Effects from 1998, The Times (London), January 23 2007

- ↑ [2] Mother Wonders if Psychosis Drug Helped Kill Son, New York Times, January 4 2007

- ↑ [3] Lilly to Pay Up to $500 Million to Settle Claims. The New York Times, January 4 2007

External links

Manufacturer site

- Zyprexa.com - 'Zyprexa (Olanzapine): Opening the Door to Possibility' (Eli Lilly's official Zyprexa brand website)

- "Zyprexa package insert" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 13 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-18. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Consumer information

- NIH.gov - 'Olanzapine for schizophrenia', Duggan Lorna, Fenton M, Rathbone J, Dardennes R, El-Dosoky A, Indran S., Cochrane Review (2005)

- MedLibrary.org - 'Information on Zyprexa and How to Use It, Precautions and Other Medications to Avoid While Taking, MedLibrary

- NIH.gov - 'Olanzapine (Systemic)' Drug Information, MedlinePlus

- PsychEducation.org - 'Zyprexa (olanzapine)' (updated April, 2004)

Controversy

- Sickening Meds Part I: Zyprexa - by A.Etzioni - Call for transparency in the pharmaceutical industry, on Daily Kos.

- MindFreedom.org - 'Info on "Zyprexa Kills" Campaign', MindFreedom International

- nytyimes.com - Lilly Settles With 18,000 Over Zyprexa, Alex Berenson, New York Times (December 17, 2006)

- Zyprexa.pbwiki.com - 'Zyprexa Kills' campaign (with links to the Eli Lilly Memos)

- ZyprexaKills.ath.cx - Leaked Memos on BitTorrent

- Youtube Eli Lilly Rep Talks about Zyprexa

- Zyprexa Injury Clock Ticking Away - Signs of the Times (2007)

da:Zyprexa de:Olanzapin it:Olanzapina hu:Olanzapin nl:Olanzapine fi:Olantsapiini sv:Olanzapin

- Pages with script errors

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 errors: dates

- Pages with citations lacking titles

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- E number from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2007

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Atypical antipsychotics

- Eli Lilly and Company

- Thiophenes

- Piperazines