Herpes simplex

For patient information on congenital herpes, click here

For patient information on genital herpes, click here

| Herpes simplex | |

| |

|---|---|

| Electron micrograph of Herpes simplex virus. | |

| ICD-10 | A60, B00, G05.1, P35.2 |

| ICD-9 | 054.0, 054.1, 054.2, 054.3, 771.2 |

| DiseasesDB | 5841 Template:DiseasesDB2 |

| MeSH | D006561 |

|

Herpes simplex Microchapters |

|

Patient Information |

|

Classification |

|

Herpes simplex On the Web |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1], Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology & Demographics

Subtypes

Several distinct disorders are caused by HSV infection of the skin or mucosa including those that affect the face and mouth (orofacial herpes), genitalia (genital herpes), or hands (herpes whitlow). More serious problems arise when the virus infects and damages the eye (herpes keratitis) or invades the central nervous system to damage the brain (herpes encephalitis). Newborn infants, with their under-developed immune systems, are also prone to serious complications due to HSV infection (neonatal herpes).

- Orofacial infection

- Anogenital infection

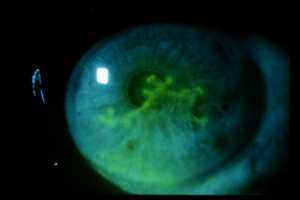

- Ocular infection

- Herpes Encephalitis

- Neonatal herpes

- Herpetic whitlow

- Herpes gladiatorum

Viral meningitis

HSV-2 is the most common cause of recurrent viral meningitis called Mollaret's meningitis.[1][2] This condition was first described in 1944 by French neurologist Pierre Mollaret. Recurrences usually last a few days or a few weeks, and resolve without treatment. They may recur weekly or monthly for approximately 5 years following primary infection.[3]

Bell's palsy

A type of facial paralysis called Bell's palsy has been linked to the presence and reactivation of latent HSV-1 inside the sensory nerves of the face known as geniculate ganglia, particularly in a mouse model.[4][5] This is supported by findings that show the presence of HSV-1 DNA in saliva at a higher frequency in patients with Bell's palsy relative to those without the condition.[6] However, since HSV can also be detected in these ganglia in large numbers of individuals that have never experienced facial paralysis, and high titers of antibodies for HSV are not found in HSV-infected individuals with Bell's palsy relative to those without, this theory has been contested.[7] Other studies, which fail to detect HSV-1 DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of Bell's palsy sufferers, also question whether HSV-1 is the causative agent in this type of facial paralysis.[8][9] The potential effect of HSV-1 in the etiology of Bell's palsy has prompted the use of antiviral medication to treat the condition. The benefits of acyclovir and valacyclovir have been studied.[10]

Alzheimer's disease

Scientists discovered a link between Herpes Simplex Type I and Alzheimer’s Disease in 1979.[11] In the presence of a certain gene variation (APOE-epsilon4 allele carriers), HSV type 1 appears to be particularly damaging to the nervous system and increases one’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The virus interacts with lipoproteins, their components, and their receptors in the brain which may lead to the development of the disease.[12] This now makes the virus the pathogen most clearly linked to the establishment of Alzheimer’s.[13] It is important to note, however, that without the presence of the gene allele, HSV type 1 does not appear to cause any neurological damage and thus increase the risk of Alzheimer’s.[14]

Recurrences and triggers

Following active infection, herpes viruses become quiescent to establish a latent infection in sensory and autonomic ganglia of the nervous system. The double-stranded DNA of the virus is incorporated into the cell physiology by infection of the cell nucleus of a nerve's cell body. HSV latency is static - no virus is produced - and is controlled by a number of viral genes including Latency Associated Transcript (LAT).[15]

The causes of reactivation from latency are uncertain but several potential triggers have been documented. Physical or psychological stress can trigger an outbreak of herpes.[16] Local injury to the face, lips, eyes or mouth, trauma, surgery, wind, radiotherapy, ultraviolet light or sunlight are well established triggers.[17][18][19][20][21] Some studies suggest changes in the immune system during menstruation may play a role in HSV-1 reactivation.[22][23] In addition, concurrent infections, such as viral upper respiratory tract infection or other febrile diseases, can cause outbreaks, hence the historic terms "cold sore" and "fever blister".

The frequency and severity of recurrent outbreaks may vary greatly depending upon the individual. Outbreaks may occur at the original site of the infection or in close proximity to nerve endings that reach out from the infected ganglia. In the case of a genital infection, sores can appear near the base of the spine, the buttocks, back of the thighs, or they may appear at the original site of infection. Immunocompromised individuals may experience episodes that are longer, more frequent and more severe. The human body is able to build up an immunity to the virus over time and antiviral medication has been proven to shorten the duration and/or frequency of the outbreaks.[24]

Transmission and prevention

Herpes can be contracted through direct contact with an active lesion or body fluid of an infected person.[25] Infected people that show no visible symptoms may still shed and transmit virus through their skin, and this asymptomatic shedding may represent the most common form of HSV-2 transmission.[26] There are no documented cases of infection via an inanimate object (e.g. a towel, toilet seat, drinking vessels). To infect a new individual, HSV travels through tiny breaks in the skin or mucous membranes in the mouth or genital areas. Even microscopic abrasions on mucous membranes are sufficient to allow viral entry. Herpes transmission occurs between discordant partners; a person with a history of infection (HSV seropositive) can pass the virus to an HSV seronegative person.[27] Antibodies that develop following an initial infection with that type of HSV prevents reinfection with the same herpes type - a person with a history of a cold sore caused by HSV-1 cannot contract a herpes whitlow or genital infection caused by HSV-1. In a monogamous couple, a seronegative female runs a >30% per year risk of contracting an HSV-1 infection from a seropositive male partner. If an oral HSV-1 infection is contracted first, seroconversion will have occurred after 6 weeks to provide protective antibodies against a future genital HSV-1 infection.

For genital herpes, condoms are a highly effective in limiting transmission of herpes simplex infection.[28][29] However, condoms are by no means completely effective. The virus cannot get through latex, but their effectiveness is somewhat limited on a public health scale by the limited use of condoms in the community,[30] and on an individual scale because the condom may not completely cover blisters on the penis of an infected male, or base of the penis or testicles not covered by the condom may come into contact with free virus in vaginal fluid of an infected female. In such cases, abstinence from sexual activity, or washing of the genitals after sex, is recommended. The use of condoms or dental dams also limits the transmission of herpes from the genitals of one partner to the mouth of the other (or vice versa) during oral sex. When one partner has herpes simplex infection and the other does not, the use of antiviral medication, such as valaciclovir, in conjunction with a condom, further decreases the chances of transmission to the uninfected partner.[27] Topical microbicides contain chemicals that directly inactivate the virus and block viral entry are currently being investigated.[27] Vaccines for HSV are currently undergoing trials. Once developed, they may be used to help with prevention or minimize initial infections as well as treatment for existing infections. [31]

As with almost all sexually transmited infections, women are more susceptible to acquiring genital HSV-2 than men.[32] On an annual basis, without the use of antivirals or condoms, the transmission risk of HSV-2 from infected male to female is approximately 8-10%. This is believed to be due to the increased exposure of mucosal tissue to potential infection sites. Transmission risk from infected female to male is approximately 4-5% annually. Suppressive antiviral therapy reduces these risks by 50%. Antivirals also help prevent the development of symptomatic HSV in infection scenarios by about 50%, meaning the infected partner will be seropositive but symptom free. Condom use also reduces the transmission risk by 50%. Condom use is much more effective at preventing male to female transmission than vice-versa. [28] The effects of combining antiviral and condom use is roughly additive, thus resulting in approximately a 75% combined reduction in annual transmission risk. These figures reflect experiences with subjects having frequently-recurring genital herpes (>6 recurrences per year). Subjects with low recurrence rates and those with no clinical manifestations were excluded from these studies.

To prevent neonatal infections, seronegative women are recommended to avoid unprotected oral-genital contact with an HSV-1 seropositive partner and conventional sex with a partner having a genital infection during the last trimester of pregnancy. Mothers infected with HSV, are advised to avoid procedures that would cause trauma to the infant during birth (e.g. fetal scalp electrodes, forceps and vacuum extractors) and, should lesions be present, to elect caesarean section to reduce exposure of the child to infected secretions in the birth canal.[27] The use of antiviral treatments, such as aciclovir, given from the 36th week of pregnancy limits HSV recurrence and shedding during childbirth, thereby reducing the need for caesarean section.[27]

HSV seropositive individuals practising unprotected sex with HIV positive persons pose a high risk of HIV transmission, and are even more susceptible to HIV during an outbreak with active sores.[33]

Asymptomatic shedding

HSV asymptomatic shedding occurs at some time in most individuals infected with herpes. It is believed to occur on 2.9% of days while on antiviral therapy, versus 10.8% of days without and is estimated to account for one third of the total days of viral shedding.[26] Asymptomatic shedding is more frequent within the first 12 months of acquiring HSV, and concurrent infection with HIV also increases the frequency and duration of asymptomatic shedding.[34] It can occur more than a week before or after a symptomatic recurrence in 50% of cases.[26] There are some indications that some individuals may have much lower patterns of shedding, but evidence supporting this is not fully verified - no significant differences are seen in the frequency of asymptomatic shedding when comparing persons with 1 to 12 annual recurrences to those that have no recurrences.[26]

Diagnosis

Primary orofacial herpes is readily identified by clinical examination in persons without a previous history of lesions, and with reported contact with an individual with known HSV-1 infection. The appearance and distribution of sores, in these individuals, typically presents as multiple, round, and superficial oral ulcers, accompanied by acute gingivitis.[35] Adults with non-typical presentation are more difficult to diagnose. However, prodromal symptoms that occur before the appearance of herpetic lesions helps to differentiate HSV symptoms from the similar symptoms of, for example, allergic stomatitis. Occasionally, when lesions do not appear inside the mouth, primary orofacial herpes is mistaken for a bacterial infection known as impetigo. Common mouth ulcers (aphthous ulcer), also resemble intraoral herpes, but do not present a vesicular stage.[35]

Genital herpes can be more difficult to diagnose than oral herpes since most HSV-2-infected persons have no classical signs and symptoms.[35] To confuse diagnosis, several other conditions resemble genital herpes, including lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, or urethritis.[35] Laboratory testing is, therefore, often used to confirm genital herpes. Laboratory tests include culture of the virus, direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) studies to detect virus, skin biopsy, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to test for presence of viral DNA. A Tzanck test (or smear), can also be performed although this cannot differentiate between herpes simplex or varicella (chicken pox) (the primary infection of varicella zoster virus (VZV or shingles). Although these procedures produce highly sensitive and specific diagnoses, their high costs and time constraints discourage their regular use in clinical practice.[35] Serological tests for antibodies to HSV are rarely useful to diagnosis but are important in epidemiological studies. Serologic assays cannot differentiate between antibodies generated in response to a genital versus an oral HSV infection and as such cannot confirm the site of infection. Absence of antibody to HSV-2 does not exclude gential infection because of the increasing incidence of genital infections caused by HSV-1. For these reasons and the diagnostic delay; serology is not routinely used in clinical practice[35]

Physical Examination

Skin

Eyes

Treatment

Currently, there is no treatment that can eradicate any of the herpes viruses from the body. Non-prescription analgesics can reduce pain and fever during initial outbreaks. Topical anesthetic treatment (such as prilocaine, lidocaine or tetracaine) can relieve itching and pain.[38][39]

Antiviral Medication

Antiviral medications used against herpes viruses work by interfering with viral replication, effectively slowing the replication rate of the virus and providing a greater opportunity for the immune response to intervene. All drugs in this class depend on the activity of the viral enzyme, thymidine kinase, to convert the drug sequentially from its prodrug form to a monophosphate (with one phosphate group), diphosphate (with two phosphate groups) and, finally, triphosphate (with three phosphate groups) form that interferes with viral DNA replication.[40]

There are several prescription antiviral medications for controlling herpes simplex outbreaks, including aciclovir (Zovirax), valaciclovir (Valtrex), famciclovir (Famvir), and penciclovir. Aciclovir was the original and prototypical member of this drug class and is now available in generic brands at a greatly reduced cost. Valaciclovir and famciclovir are prodrugs of aciclovir and penciclovir respectively, which have improved solubility in water and better bioavailability when taken orally.[40] Aciclovir is the recommended antiviral for suppressive therapy in the last months of pregnancy to prevent transmission of herpes simplex to the neonate.[41] The use of valaciclovir and famciclovir, while potentially improving treatment compliance and efficacy, are still undergoing safety evaluation in this context. There is evidence in mice that treatment with famciclovir, rather than aciclovir, during an initial outbreak can help lower the incidence of future outbreaks by reducing the amount of latent virus in the neural ganglia. This potential effect on latency over aciclovir drops to zero a few months post-infection.[42] Antiviral medications are also available as topical creams for treating recurrent outbreaks on the lips although their effectiveness is disputed.[43] Penciclovir cream has a far longer cellular half-life than aciclovir cream – 10-20 hours for penciclovir versus 3 hours for aciclovir - increasing its effectiveness relative to aciclovir when topically applied.[44]

Topical treatments

Docosanol is available as a cream for direct application to the affected area of skin. It prevents HSV from fusing to cell membranes, thus barring the entry of the virus into the skin. Docosanol was approved for use after clinical trials by the FDA in July 2000.[45] Marketed by Avanir Pharmaceuticals under the brand name Abreva, it was the first over-the-counter antiviral drug approved for sale in the United States and Canada and was the subject of a US nationwide class-action suit in March, 2007 due to the misleading claim that it cut recovery times in half.[46] Tromantadine is available as a gel that inhibits entry and spreading of the virus by altering the surface composition of skin cells and inhibiting release of viral genetic material. Zilactin is a topical analgesic barrier treatment, which forms a "shield" at the area of application to prevents a sore from increasing in size and decrease viral spreading during the healing process.

Other drugs

Cimetidine, a common component of heartburn medication, has been shown to lessen the severity of herpes zoster outbreaks in several different instances, and offered some relief from herpes simplex.[47][48][49] This is an off-label use of the drug. It and probenecid have been shown to reduce the renal clearance of aciclovir.[50] These compounds also reduce the rate, but not the extent, at which valaciclovir is converted into aciclovir.

Limited evidence suggests that low dose aspirin (125 mg daily) might be beneficial in patients with recurrent HSV infections. Aspirin (also called acetylsalicylic acid) is an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, which reduces the level of prostaglandins - naturally occurring lipid compounds - that are essential in creating inflammation.[51] A recent study in animals showed inhibition of thermal (heat) stress-induced viral shedding of HSV-1 in the eye by aspirin, and a possible benefit in reducing the frequency of recurrences.[52]

Vaccines

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States is currently in the midst of phase III trials of a vaccine against HSV-2, called Herpevac.[53] The vaccine has only been shown to be effective for women who have never been exposed to HSV-1. Overall, the vaccine is approximately 48% effective in preventing HSV-2 seropositivity and about 78% effective in preventing symptomatic HSV-2.[53] Assuming FDA approval, a commercial version of the vaccine is estimated to become available around 2008. During initial trials, the vaccine did not exhibit any evidence in preventing HSV-2 in males.[53] Additionally, the vaccine only reduced the acquisition of HSV-2 and symptoms due to newly acquired HSV-2 among women who did not have HSV-2 infection at the time they got the vaccine.[53] Because about 20% of persons in the United States have HSV-2 infection, this further reduces the population for whom this vaccine might be appropriate.[53]

Natural compounds

|

|

|

| Some individuals seek benefits in natural products and dietary supplements for treatment of herpes |

Certain dietary supplements and alternative remedies are believed beneficial in the treatment of herpes when used in conjunction with conventional antiviral therapy. However, there is currently insufficient scientific and clinical evidence to support the safe or effective use of these compounds to treat herpes in humans.[54]

Aloe vera is available as cream or gel which makes an affected area heal faster, and may even prevent recurrences.[55] Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), has antiviral activity against HSV-2 in cell culture, and may reduce HSV symptoms in herpes infected people.[56][57][57] Carrageenans - linear sulphated polysaccharides extracted from red seaweeds - have been shown to have antiviral effects in HSV-infected cells and in mice.[58]However, there is no evidence for efficacy of this compound in humans.[59] There are conflicting reports about the effectiveness of extracts from the plant echinacea in treating herpes infections, suggesting a possible benefit for treating oral, but not genital, herpes.[60][61] Resveratrol, a compound naturally produced by plants and a component of red wine, prevents HSV replication in cultured cells and reduces cutaneous HSV lesion formation in mice although, used alone, it is not considered potent enough to be an effective treatment.[62][63] Extracts from garlic have shown antiviral activity against HSV in cell culture experiments, although the extremely high concentrations of the extracts required to produce an antiviral effect was also toxic to the cells.[64] The plant Prunella vulgaris, commonly known as "selfheal", also prevents expression of both type 1 and type 2 herpes in cultured cells.[65]

Lactoferrin, a component of whey protein, has been shown to have a synergistic effect with aciclovir against HSV in vitro.[66] Lysine supplementation has been proposed for the prophylaxis and treatment of herpes simplex when used at high doses (exceeding 1000 mg per day) but not low doses.[67][68][69] Some dietary supplements have been suggested to positively treat herpes. These include vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin E, and zinc.[70][71] Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), commonly available as a food preservative, has been shown in cell culture and animal studies to inactivate herpes virus.[72] [73] However BHT has not been clinically tested and approved to treat herpes infections in humans.

Psychological and social effects

Since there is currently no cure for herpes, some people experience negative feelings related to the condition following diagnosis, particularly if they have acquired the genital form of the disease. Though these feelings lessen over time, they can include depression, fear of rejection, feelings of isolation, fear of being found out, self-destructive feelings, and fear of masturbation.[74] In order to improve the well-being of people with herpes, support groups have been formed in the United States and the UK, providing supporting communities and information about herpes of message forums and dating websites.[75][76][77][78][79]

People with the herpes virus are often hesitant to divulge to other people, including friends and family, that they are infected. This is especially true of new or potential sexual partners that they consider 'casual'.[80] A perceived reaction is sometimes taken into account before making a decision about whether to inform new partners and at what point in the relationship. Many people choose not to disclose their herpes status when they first begin dating someone, but wait until it later becomes clear that they are moving towards a sexual relationship. Other people disclose their herpes status upfront. Still others choose only to date other people who already have herpes.

Legal redress

Whether the law can help a person who catches herpes depends on the jurisdiction where it was contracted as legal jurisdictions define their own rules regarding the transmission of STIs such as herpes.[81] There can be both criminal and civil possibilities. For example, in the criminal case of R. v. Sullivan heard in England and Wales, an attempt was made to prosecute Sullivan for sexual assault after his partner experienced a primary outbreak of genital herpes, on the basis that he had failed to reveal the fact that he had herpes. The presiding judge dismissed the prosecution case during preliminary hearings, citing inability to prove prior knowledge and the trial did not take place.[82] Civil claims for transmission of herpes are, for their part, usually based on negligence if transmission was accidental and battery if deliberate. The first successful case to allow such a claim in the United States was Kathleen K. v. Robert B., decided by the California Court of Appeals.[83]

References

- ↑

- ↑ Sendi P, Graber P (2006). "Mollaret's meningitis". CMAJ. 174 (12): 1710. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051688. PMID 16754896.

- ↑ Takasu T, Furuta Y, Sato KC, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y, Nagashima K (1992). "Detection of latent herpes simplex virus DNA and RNA in human geniculate ganglia by the polymerase chain reaction". Acta Otolaryngol. 112 (6): 1004–11. PMID 1336296.

- ↑ Sugita T, Murakami S, Yanagihara N, Fujiwara Y, Hirata Y, Kurata T (1995). "Facial nerve paralysis induced by herpes simplex virus in mice: an animal model of acute and transient facial paralysis". Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 104 (7): 574–81. PMID 7598372.

- ↑ Lazarini PR, Vianna MF, Alcantara MP, Scalia RA, Caiaffa Filho HH (2006). "[Herpes simplex virus in the saliva of peripheral Bell's palsy patients]". Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) (in Portuguese). 72 (1): 7–11. PMID 16917546.

- ↑ Linder T, Bossart W, Bodmer D (2005). "Bell's palsy and Herpes simplex virus: fact or mystery?". Otol. Neurotol. 26 (1): 109–13. PMID 15699730.

- ↑ Kanerva M, Mannonen L, Piiparinen H, Peltomaa M, Vaheri A, Pitkäranta A (2007). "Search for Herpesviruses in cerebrospinal fluid of facial palsy patients by PCR". Acta Otolaryngol. 127 (7): 775–9. doi:10.1080/00016480601011444. PMID 17573575.

- ↑ Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Skoog E, Aurelius E (2006). "Detection of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses in patients with Bell's palsy by the polymerase chain reaction technique". Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 115 (4): 306–11. PMID 16676828.

- ↑ Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N (2007). "Bell's palsy: diagnosis and management". Am Fam Physician. 76 (7): 997–1002. PMID 17956069.

- ↑ Middleton PJ, Peteric M, Kozak M, Rewcastle NB, McLachlan DR. (1980). "Herpes simplex viral genome and senile and presenile dementias of Alzheimer and Pick". Lancet: 1038.

- ↑ Dobson, C.B. (1999). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer's disease". Neurobiol Aging. 20 (4): 457–65. Retrieved 2008-03-15. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Pyles, R.B. (2001). "The association of herpes simplex virus and Alzheimer's disease: a potential synthesis of genetic and environmental factors" (PDF). Herpes. 8 (3): 64–68. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ↑ Itzhaki, R.F. (1997). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer's disease". Lancet. 349 (9047): 241–4. Retrieved 2008-03-15. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Stumpf MP, Laidlaw Z, Jansen VA (2002). "Herpes viruses hedge their bets". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (23): 15234–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.232546899. PMID 12409612.

- ↑ Sainz B, Loutsch JM, Marquart ME, Hill JM (2001). "Stress-associated immunomodulation and herpes simplex virus infections". Med. Hypotheses. 56 (3): 348–56. doi:10.1054/mehy.2000.1219. PMID 11359358.

- ↑ Chambers A, Perry M (2008). "Salivary mediated autoinoculation of herpes simplex virus on the face in the absence of "cold sores," after trauma". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 66 (1): 136–8. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2006.07.019. PMID 18083428.

- ↑ Perna JJ, Mannix ML, Rooney JF, Notkins AL, Straus SE (1987). "Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus infection by ultraviolet light: a human model". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 17 (3): 473–8. PMID 2821086.

- ↑ Rooney JF, Straus SE, Mannix ML; et al. (1992). "UV light-induced reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 2 and prevention by acyclovir". J. Infect. Dis. 166 (3): 500–6. PMID 1323616.

- ↑ Oakley C, Epstein JB, Sherlock CH (1997). "Reactivation of oral herpes simplex virus: implications for clinical management of herpes simplex virus recurrence during radiotherapy". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 84 (3): 272–8. PMID 9377190.

- ↑ Ichihashi M, Nagai H, Matsunaga K (2004). "Sunlight is an important causative factor of recurrent herpes simplex". Cutis. 74 (5 Suppl): 14–8. PMID 15603217.

- ↑ Myśliwska J, Trzonkowski P, Bryl E, Lukaszuk K, Myśliwski A (2000). "Lower interleukin-2 and higher serum tumor necrosis factor-a levels are associated with perimenstrual, recurrent, facial Herpes simplex infection in young women". Eur. Cytokine Netw. 11 (3): 397–406. PMID 11022124.

- ↑ Segal AL, Katcher AH, Brightman VJ, Miller MF (1974). "Recurrent herpes labialis, recurrent aphthous ulcers, and the menstrual cycle". J. Dent. Res. 53 (4): 797–803. PMID 4526372.

- ↑ Martinez V, Caumes E, Chosidow O (2008). "Treatment to prevent recurrent genital herpes". Curr Opin Infect Dis. 21 (1): 42–48. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f3d9d3. PMID 18192785.

- ↑ "AHMF: Preventing Sexual Transmission of Genital Herpes". Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Wald A, Langenberg AG, Link K, Izu AE, Ashley R, Warren T, Tyring S, Douglas JM Jr, Corey L. (2001). "Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women". JAMA. 285 (24): 3100–3106. PMID 11427138.

- ↑ Casper C, Wald A. (2002). "Condom use and the prevention of genital herpes acquisition". Herpes. 9 (1): 10–14. PMID 11916494.

- ↑ de Visser RO, Smith AM, Rissel CE, Richters J, Grulich AE. (2003). "Sex in Australia: safer sex and condom use among a representative sample of adults". Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 27 (2): 223–229. PMID 14696715.

- ↑ Seppa, Nathan (2005-01-05). "One-Two Punch: Vaccine fights herpes with antibodies, T cells". Science News. p. 5. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ Carla K. Johnson (August 23, 2006). "Percentage of people with herpes drops". Associated Press.

- ↑ Koelle DM, Corey L (2008). "Herpes Simplex: Insights on Pathogenesis and Possible Vaccines". Annu Rev Med. 59: 381–395. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.59.061606.095540. PMID 18186706.

- ↑ Kim H, Meier A, Huang M, Kuntz S, Selke S, Celum C, Corey L, Wald A (2006). "Oral herpes simplex virus type 2 reactivation in HIV-positive and -negative men". J Infect Dis. 194 (4): 420–7. PMID 16845624.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA (2007). "Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 57 (5): 737–63, quiz 764–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.027. PMID 17939933.

- ↑ http://picasaweb.google.com/mcmumbi/USMLEIIImages/

- ↑ http://picasaweb.google.com/mcmumbi/USMLEIIImages/

- ↑ "Local anesthetic creams". BMJ. 297 (6661): 1468. 1988. PMID 3147021.

- ↑ Kaminester LH, Pariser RJ, Pariser DM; et al. (1999). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of topical tetracaine in the treatment of herpes labialis". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 41 (6): 996–1001. PMID 10570387.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 De Clercq E, Field HJ (2006). "Antiviral prodrugs - the development of successful prodrug strategies for antiviral chemotherapy". Br. J. Pharmacol. 147 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706446. PMID 16284630.

- ↑ Leung DT, Sacks SL. (2003). "Current treatment options to prevent perinatal transmission of herpes simplex virus". Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 4 (10): 1809–1819. PMID 14521490.

- ↑ Thackray AM, Field HJ. (1996). "Differential effects of famciclovir and valaciclovir on the pathogenesis of herpes simplex virus in a murine infection model including reactivation from latency". J. Infect. Dis. 173 (2): 291–299. PMID 8568288.

- ↑ Worrall G (1996). "Evidence for efficacy of topical acyclovir in recurrent herpes labialis is weak". BMJ. 313 (7048): 46. PMID 8664786.

- ↑ Spruance SL, Rea TL, Thoming C, Tucker R, Saltzman R, Boon R (1997). "Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group". JAMA. 277 (17): 1374–9. PMID 9134943.

- ↑ "Drug Name: ABREVA (docosanol) - approval". centerwatch.com. July 2000. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ "California Court Upholds Settlement Of Class Action Over Cold Sore Medicationl". BNA Inc. July 2000. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑

Another treatment, if not very medical, is the use of vaseline, or any other type of fat. This will ban water, or saliva, from reaching the cold sore. as the cold sore "feeds" itself from water, this will end its existence in a day or two.

Kapinska-Mrowiecka M, Toruwski G (1996.). "Efficacy of cimetidine in treatment of herpes zoster in the first 5 days from the moment of disease manifestation". Pol Tyg Lek. 51 (23–26): 338–339. PMID 9273526. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Hayne ST, Mercer JB (1983). "Herpes zoster:treatment with cemetidine". Can Med Assoc J. 129 (12): 1284–1285. PMID 6652595.

- ↑ Komlos L, Notmann J, Arieli J, et.al. (1994). "In vitro cell-mediated immune reactions in herpes zoster patients treated with cimetidine". Asian Pac J Allelrgy Immunol. 12 (1): 51–58. PMID 7872992.

- ↑ De Bony F, Tod M, Bidault R, On NT, Posner J, Rolan P. (2002). "Multiple interactions of cimetidine and probenecid with valaciclovir and its metabolite acyclovir". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 (2): 458–463. PMID 11796358.

- ↑ Karadi I, Karpati S, Romics L. (1998). "Aspirin in the management of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection". Ann. Intern. Med. 128 (8): 696–697. PMID 9537952.

- ↑ Gebhardt BM, Varnell ED, Kaufman HE. (2004). "Acetylsalicylic acid reduces viral shedding induced by thermal stress". Curr. Eye Res. 29 (2–3): 119–125. PMID 15512958.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 "Herpevac Trial for Women". Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ Perfect MM, Bourne N, Ebel C, Rosenthal SL (2005). "Use of complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of genital herpes". Herpes. 12 (2): 38–41. PMID 16209859.

- ↑ Vogler BK and Ernst E. "Aloe vera: a systematic review of its clinical effectiveness". British Journal of General Practice. 49: 823–828.

- ↑ Allahverdiyev A, Duran N, Ozguven M, Koltas S. (2004). "Antiviral activity of the volatile oils of Melissa officinalis L. against Herpes simplex virus type-2". Phytomedicine. 11 (7–8): 657–661. PMID 15636181.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Koytchev R, Alken RG, Dundarov S (1999). "Balm mint extract (Lo-701) for topical treatment of recurring herpes labialis". Phytomedicine. 6 (4): 225–30. PMID 10589440.

- ↑ Zacharopoulos VR, Phillips DM. (1997). "Vaginal formulations of carrageenan protect mice from herpes simplex virus infection". Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4 (4): 465–468. PMID 9220165.

- ↑ Carlucci MJ, Scolaro LA, Damonte EB. (1999). "Inhibitory action of natural carrageenans on Herpes simplex virus infection of mouse astrocytes". Chemotherapy. 45 (6): 429–436. PMID 10567773.

- ↑ Binns SE, Hudson J, Merali S, Arnason JT (2002). "Antiviral activity of characterized extracts from echinacea spp. (Heliantheae: Asteraceae) against herpes simplex virus (HSV-I)". Planta Med. 68 (9): 780–3. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34397. PMID 12357386.

- ↑ Vonau B, Chard S, Mandalia S, Wilkinson D, Barton SE (2001). "Does the extract of the plant Echinacea purpurea influence the clinical course of recurrent genital herpes?". Int J STD AIDS. 12 (3): 154–8. PMID 11231867.

- ↑ Docherty JJ, Fu MM, Stiffler BS, Limperos RJ, Pokabla CM, DeLucia AL. (1999). "Resveratrol inhibition of herpes simplex virus replication". Antiviral Res. 43 (3): 145–155. PMID 10551373.

- ↑ Docherty JJ, Smith JS, Fu MM, Stoner T, Booth T. (2004). "Effect of topically applied resveratrol on cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections in hairless mice". Antiviral Res. 61 (1): 19–26. PMID 14670590.

- ↑ Weber ND, Andersen DO, North JA, Murray BK, Lawson LD, Hughes BG (1992). "In vitro virucidal effects of Allium sativum (garlic) extract and compounds". Planta Med. 58 (5): 417–23. PMID 1470664.

- ↑ Chiu LC, Zhub W, Oo VE (2004). "A polysaccharide fraction from medicinal herb Prunella vulgaris downregulates the expression of herpes simplex virus antigen in Vero cells". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 93 (1): 63–68.

- ↑ Andersen JH, Jenssen H, Gutteberg TJ. (2003). "Lactoferrin and lactoferricin inhibit Herpes simplex 1 and 2 infection and exhibit synergy when combined with acyclovir". Antiviral Res. 58 (3): 209–215. PMID 12767468.

- ↑ McCune MA, Perry HO, Muller SA, O'Fallon WM. (2005). "Treatment of recurrent herpes simplex infections with L-lysine monohydrochloride". Cutis. 34 (4): 366–373. PMID 6435961.

- ↑ Griffith RS, Walsh DE, Myrmel KH, Thompson RW, Behforooz A. (1987). "Success of L-lysine therapy in frequently recurrent herpes simplex infection. Treatment and prophylaxis". Dermatologica. 175 (4): 183–190. PMID 3115841.

- ↑ Griffith RS, Norins AL, Kagan C. (1978). "A multicentered study of lysine therapy in Herpes simplex infection". Dermatologica. 156 (5): 257–267. PMID 640102.

- ↑ Gaby AR (2006). "Natural remedies for Herpes simplex". Altern Med Rev. 11 (2): 93–101. PMID 16813459.

- ↑ Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G (2006). "Recurrent herpes labialis during isotretinoin therapy: is there a role for photosensitivity?". J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 20 (1): 93–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01358.x. PMID 16405618.

- ↑ Snipes W, Person S, Keith A, Cupp J. "Butylated hydroxytoluene inactivates lipid-containing viruses" Science. 1975;188(4183):64-6

- ↑ Richards JT, Katz ME, Kern ER. "Topical butylated hydroxytoluene treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infections of guinea pigs" Antiviral Res 1985;5(5):281-90

- ↑ Vezina C, Steben M. (2001). "Genital Herpes: Psychosexual Impacts and Counselling". The Canadian Journal of CME (June): 125–134.

- ↑ Herpes Support Groups & Clinics

- ↑ Herpes Viruses Association - a patient run group

- ↑ Herpes message forum with over 4000 members

- ↑ H-Date, a dating site for persons with either or both of HSV-1 or HSV-2

- ↑ MPwH - Meeting People with Herpes, a dating site with over 65000 members

- ↑ Green J, Ferrier S, Kocsis A, Shadrick J, Ukoumunne OC, Murphy S, Hetherton J. (2003). "Determinants of disclosure of genital herpes to partners". Sex. Transm. Infect. 79 (1): 42–44. PMID 12576613.

- ↑ Webpage on social aspects of genital herpes

- ↑ "The transmission of HIV as a criminal offence". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Gold-bikin, L.Z. [?hl=en&lr=&ie=UTF-8&q=info:5smAUslPm8sJ:scholar.google.com/&output=viewport "Herpes Breeds New Legal Epidemic: Fraud and Negligence Suits"] Check

|url=value (help). Family Advocate. 7: 26. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

External links

General

- Genital Herpes Fact Sheet at The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Paper - Genital Herpes: A Hidden Epidemic at FDA

Images

- Links to genital herpes pictures (Hardin MD/University of Iowa

- Herpes photo library at Dermnet

- Pictures of Orofacial Herpes (Coldsores) (VisualDxHealth)

- Genital Herpes Pictures

Other

- Herpes Blood Tests Quick Reference Guide

- Updated Herpes Handbook from Westover Heights Clinic

- "The Importance and Practicalities of Patient Counseling in the Prevention and Management of Genital Herpes" (2004) at Medscape

- International Herpes Management Forum

- Provides Ratios of Lysine to Arginine in Common Foods

Template:STD/STI Template:Viral diseases

cs:Jednoduchý opar

da:Herpes

de:Herpes

eo:Herpeto

ko:단순 포진

id:Herpes simpleks

it:Herpes

he:הרפס

ms:Herpes

nl:Genitale herpes

no:Herpesvirusinfeksjon

sk:Jednoduchý opar

sr:Херпес

sv:Herpes