Dilated cardiomyopathy: Difference between revisions

Sachin Shah (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Sachin Shah (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

'''Dilated cardiomyopathy''' or '''DCM''' is a condition of the heart that causes dilation and impaired contraction of the left ventricle (or both ventricles). Impaired contraction is defined as a low ejection fraction (< 40%). In the following text the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment will be reviewed. | '''Dilated cardiomyopathy''' or '''DCM''' is a condition of the heart that causes dilation and impaired contraction of the left ventricle (or both ventricles). Impaired contraction is defined as a low ejection fraction (< 40%). In the following text the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment will be reviewed. | ||

[[Cardimyopathy]] as a general topic also includes topics such as [[restrictive cardiomyopathy]] and [[hypertrophic cardiomyopathy]]. This section will focus on dilated cardiomyopathy. | [[Cardimyopathy]] as a general topic also includes topics such as [[restrictive cardiomyopathy]] and [[hypertrophic cardiomyopathy]]. This section will focus on dilated cardiomyopathy. There is sometimes confusion regarding nomenclature, some of this confusion is based on different classifications set forth by the WHO (World Health Organization) and the AHA (American Heart Association). The WHO classifies cardiomyopathy as either Dilated (DCM), Restrictive (RCM), or Hypertrophic (HCM). The American Heart Association classifies cardiomyopathies as either "primary" or "secondary." | ||

Dilated cardiomyopathy can occur at any age (although it is more likely between the ages of 20-60)<ref>Dec GW, Fuster V. Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1994 Dec 8;331(23):1564-75. PMID 7969328</ref> there is a male predominance,<ref>Robbins Basic Pathology, 7th edition. Kumar, Cotran, Robbins. ISBN 0-7216-9274-5</ref>, | Dilated cardiomyopathy can occur at any age (although it is more likely between the ages of 20-60)<ref>Dec GW, Fuster V. Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1994 Dec 8;331(23):1564-75. PMID 7969328</ref> there is a male predominance (3:1 male:female),<ref>Robbins Basic Pathology, 7th edition. Kumar, Cotran, Robbins. ISBN 0-7216-9274-5</ref>, and is 2.5 times more likely in African Americans.<ref>Coughlin SS, Labenberg JR, Tefft MC. Black-white differences in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: the Washington DC Dilated Cardiomyopathy Study. Epidemiology. 1993;4:165-72. PMID 8452906</ref>. There are many causes and there are varying degrees of severityof the disease . Some forms are reversible and some are irreversible; some patients may be completely asymptoamtic and some may require cardiac transplantation. | ||

==Causes== | ==Causes== | ||

There are many causes of dilated cardiomyopathy. The most common cause is "idiopathic" which accounts for roughly 50% of cases.<ref> Felker GM, Thompson RE, et al. Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000 Apr 13;342(14):1077-84.</ref> The next most common is Myocarditis which accounts for roughly 10%. Ischemic "cardiomyopathy," infiltrative disease, hypertensive heart disease, substance abuse (i.e. alcohol abuse or cocaine abuse), connective tissue disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, drugs (such as the chemotherapeutic agent doxarubacin), HIV infection or antiretroviral drugs, toxins (such as cobalt, lead or beryllium), and nutritional deficiencies (such as thiamine or selenium) are among other causes of dilated cardiomyopathy. | |||

</ref> | |||

The high percentage of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy may be related to the difficulty in diagnosing viral myocarditis. There are not definitive diagnostic criteria for myocarditis based on echocardiography, the clinical presentation is commonly similar to dilated cardiomyopathy from other causes, and the sensitivity of endomycardial biopsy is relatively low and approaches near 50% even with immunostaining (CD3 for T lymphocytes and CD68 for macrophages).<ref>Herskowitz A, Ahmed-Ansari A, Neumann DA et al. Induction of major histocompatibility complex antigens within the myocardium of patients with active myocarditis: a nonhistologic marker of myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(3):624-632.</ref>. Cardiac MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) appears to be not only helpful in the localization of inflammation and targeting of endomyocardial biopsy but also seems to be helpful in the diagnosis of myocarditis.<ref>Freidrich MG, Strohm O, et al. Contrast media-enhanced mangetic resonance imaging visualizes myocardial changes in the course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1802-1809.</ref> This new technology may be helpful in reducing the percentage of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and discovering an etiology to the dilated cardiomyopathy in some of these patients. | |||

==Clinical Presentation== | |||

The clinical presentation of dilated cardiomyopathy is similar to that heart failure from any cause. Dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, lower extremity edema and orthostasis / syncope are all common findings in dilated cardiomyopathy. In addition dilated cardiomyopathy may present as palpitations as a result of arrhythmia (ventricular or atrial) with the most common arrhythmia being atrial fibrillation. Dilated cardiomyopathy may also present as sudden cardiac death or as CVA (cerebrovascular accident) or other embolic phenomenon (either from associated atrial fibrillation or from ventricular thrombi as a result of dilated ventricular cavities). | |||

== | Angina is not a common feature of dilated cardiomyopathy unless the cause is related to coronary artery disease. If angina is present a work up for cardiac ischemia should be undertaken.<ref> Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.</ref> | ||

==Diagnosis== | |||

The diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is based on clinical presentation and imaging findings. The most common imaging modality used to diagnose dilated cardiomyopathy is 2D-echocardiography. Echocardiographic findings of dilated cardiomyopathy include dilation of the left ventricle; however, may include dilation of all 4 cardiac chambers, LV (left ventricular) wall thickness usually is normal but given the dilation the LV mass is increased. In addition there is a global reduciton in systolic function. Occasionally there may also be wall motion abnormalities even in patients without flow limiting coronary artery disease.<ref> Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.</ref> | |||

The diagnosis requires a dilated left ventricle and low ejection fraction. | |||

In terms of determining the etiology a careful history is most instrumental. If the patient has CAD (coronary artery disease) risk factors, known CAD, or angina then a workup for CAD should be undertaken with coronary angiography. A viral prodrome such as viral URI or viral gastroenteritis may make viral myocarditis as a more likely cause. If the patient was exposed to chemotherapy such as anthracyclines then this would be the likely cause. Patients at risk for HIV should undergo testing as HIV can cause a dilated cardiomyopathy. Peripartum cardiomyopathy most often occurs within 1 month of delivery or 5 months after delivery, so recent childbirth is important information. Often by 8 months gestational age pregnancy is physically apparent but it is important to rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing age with dilated cardiomyopathy. Screening questions regarding cocaine or alcohol abuse or other toxin exposure (such as cobalt) should be addressed. A review of systems is also helpful in regards to connective tissue disease associated dilated cardiomyopathy (which can be related to SLE (systemic lupus erythematosis), rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, as well as other connective tissue diseases). A family history also has a great importance in the diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy. It has been suggested that a portion of those patients labeled as "idiopathic" may have a familial form of the disease. The prevalence of this in the population of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy has been estimated as high as 25%.<ref>Ross J Jr. Dilated cardiomyopathy: concepts derived from gene deficient and transgenic animal models. Circ J. 2002;66:219-24. PMID 11922267</ref> The majority of these are thought to be related to autosomal dominant transmission, the remaining are thought to be transimtted in an autosomal recessive and X-linked fashion.<ref>Mestroni L; Rocco C; et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy: evidence for genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Heart Muscle Disease Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999 Jul;34(1):181-90.</ref> Mitochondrial inheritance of the disease has also been identified.<ref>Schonberger J, Seidman CE. Many roads lead to a broken heart: the genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:249-60. Epub 2001 Jul 6. PMID 11443548</ref> | |||

Pericardial effusion may accompany myocarditis but this finding is not specific. Cardiac MRI as discussed above may be helpful in diagnosing myocarditis. Endomyocardial biopsy as discussed above has low sensitivy and the findings are also notoriously non-specific. The findings on biopsy usually involve findings of inflammation and specific pathogens are unlikely to be identified. There may be an increased yield to using MRI to target endomyocardial biopsy as described above. Viral titiers (serologies) are often unhelpful and not routinely ordered in clinical practice. | |||

The | ==Prognosis== | ||

There are many prognostic factors which can be evaluated in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy.<ref> Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.</ref> The most important prognostic indicator is a decreased ejection fraction, in addition increased ventricular size and right ventricular dilation are independent indicators of a poor prognosis. | |||

As is in most cases of heart failure a poor NYHA functional class and increased PASP (>35mmHg) are also poor prognostic indicators. | |||

Other findings that infer a poor prognosis are as follows: Maximal O2 uptake of < 12mL/kg / minute on exercise testing, LBBB (left bundle branch block), non sustained ventricular tachycardia, syncope, hyponatremia with a serum sodium less than 135, elevated norepinephrine, ANP (atrial natriuretic peptide) and renin levels (not routinely measured in clinical practice), elevated PCWP (pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) > 18mmHg, low cardiac index < 2.5L/min/m^2. | |||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

Revision as of 16:25, 3 November 2009

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

| |

|---|---|

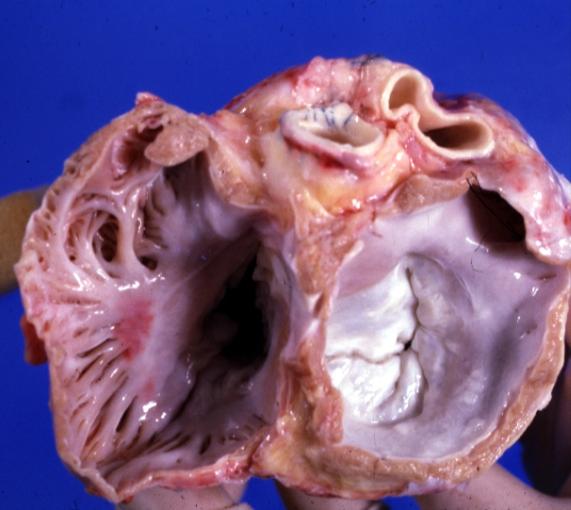

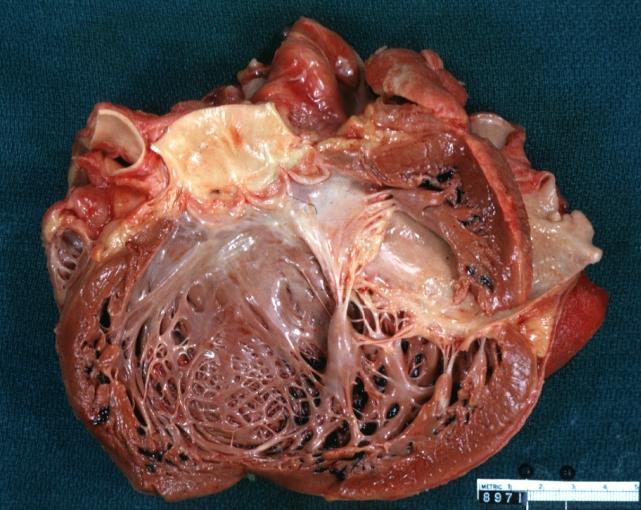

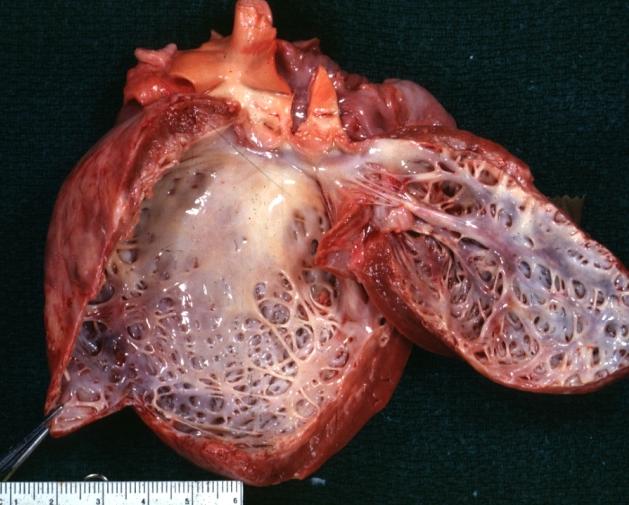

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross dilated left ventricle with marked endocardial sclerosis Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | I42.0 |

| ICD-9 | 425.4 |

| OMIM | 212110 |

| DiseasesDB | 3066 |

| MedlinePlus | 000168 |

| eMedicine | med/289 emerg/80 ped/2502 |

| MeSH | D002311 |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Dilated cardiomyopathy further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-in-Chief: Sachin Shah, M.D.

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [1] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Dilated cardiomyopathy or DCM is a condition of the heart that causes dilation and impaired contraction of the left ventricle (or both ventricles). Impaired contraction is defined as a low ejection fraction (< 40%). In the following text the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment will be reviewed.

Cardimyopathy as a general topic also includes topics such as restrictive cardiomyopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This section will focus on dilated cardiomyopathy. There is sometimes confusion regarding nomenclature, some of this confusion is based on different classifications set forth by the WHO (World Health Organization) and the AHA (American Heart Association). The WHO classifies cardiomyopathy as either Dilated (DCM), Restrictive (RCM), or Hypertrophic (HCM). The American Heart Association classifies cardiomyopathies as either "primary" or "secondary."

Dilated cardiomyopathy can occur at any age (although it is more likely between the ages of 20-60)[1] there is a male predominance (3:1 male:female),[2], and is 2.5 times more likely in African Americans.[3]. There are many causes and there are varying degrees of severityof the disease . Some forms are reversible and some are irreversible; some patients may be completely asymptoamtic and some may require cardiac transplantation.

Causes

There are many causes of dilated cardiomyopathy. The most common cause is "idiopathic" which accounts for roughly 50% of cases.[4] The next most common is Myocarditis which accounts for roughly 10%. Ischemic "cardiomyopathy," infiltrative disease, hypertensive heart disease, substance abuse (i.e. alcohol abuse or cocaine abuse), connective tissue disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, drugs (such as the chemotherapeutic agent doxarubacin), HIV infection or antiretroviral drugs, toxins (such as cobalt, lead or beryllium), and nutritional deficiencies (such as thiamine or selenium) are among other causes of dilated cardiomyopathy.

The high percentage of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy may be related to the difficulty in diagnosing viral myocarditis. There are not definitive diagnostic criteria for myocarditis based on echocardiography, the clinical presentation is commonly similar to dilated cardiomyopathy from other causes, and the sensitivity of endomycardial biopsy is relatively low and approaches near 50% even with immunostaining (CD3 for T lymphocytes and CD68 for macrophages).[5]. Cardiac MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) appears to be not only helpful in the localization of inflammation and targeting of endomyocardial biopsy but also seems to be helpful in the diagnosis of myocarditis.[6] This new technology may be helpful in reducing the percentage of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and discovering an etiology to the dilated cardiomyopathy in some of these patients.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of dilated cardiomyopathy is similar to that heart failure from any cause. Dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, lower extremity edema and orthostasis / syncope are all common findings in dilated cardiomyopathy. In addition dilated cardiomyopathy may present as palpitations as a result of arrhythmia (ventricular or atrial) with the most common arrhythmia being atrial fibrillation. Dilated cardiomyopathy may also present as sudden cardiac death or as CVA (cerebrovascular accident) or other embolic phenomenon (either from associated atrial fibrillation or from ventricular thrombi as a result of dilated ventricular cavities).

Angina is not a common feature of dilated cardiomyopathy unless the cause is related to coronary artery disease. If angina is present a work up for cardiac ischemia should be undertaken.[7]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is based on clinical presentation and imaging findings. The most common imaging modality used to diagnose dilated cardiomyopathy is 2D-echocardiography. Echocardiographic findings of dilated cardiomyopathy include dilation of the left ventricle; however, may include dilation of all 4 cardiac chambers, LV (left ventricular) wall thickness usually is normal but given the dilation the LV mass is increased. In addition there is a global reduciton in systolic function. Occasionally there may also be wall motion abnormalities even in patients without flow limiting coronary artery disease.[8]

The diagnosis requires a dilated left ventricle and low ejection fraction.

In terms of determining the etiology a careful history is most instrumental. If the patient has CAD (coronary artery disease) risk factors, known CAD, or angina then a workup for CAD should be undertaken with coronary angiography. A viral prodrome such as viral URI or viral gastroenteritis may make viral myocarditis as a more likely cause. If the patient was exposed to chemotherapy such as anthracyclines then this would be the likely cause. Patients at risk for HIV should undergo testing as HIV can cause a dilated cardiomyopathy. Peripartum cardiomyopathy most often occurs within 1 month of delivery or 5 months after delivery, so recent childbirth is important information. Often by 8 months gestational age pregnancy is physically apparent but it is important to rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing age with dilated cardiomyopathy. Screening questions regarding cocaine or alcohol abuse or other toxin exposure (such as cobalt) should be addressed. A review of systems is also helpful in regards to connective tissue disease associated dilated cardiomyopathy (which can be related to SLE (systemic lupus erythematosis), rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, as well as other connective tissue diseases). A family history also has a great importance in the diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy. It has been suggested that a portion of those patients labeled as "idiopathic" may have a familial form of the disease. The prevalence of this in the population of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy has been estimated as high as 25%.[9] The majority of these are thought to be related to autosomal dominant transmission, the remaining are thought to be transimtted in an autosomal recessive and X-linked fashion.[10] Mitochondrial inheritance of the disease has also been identified.[11]

Pericardial effusion may accompany myocarditis but this finding is not specific. Cardiac MRI as discussed above may be helpful in diagnosing myocarditis. Endomyocardial biopsy as discussed above has low sensitivy and the findings are also notoriously non-specific. The findings on biopsy usually involve findings of inflammation and specific pathogens are unlikely to be identified. There may be an increased yield to using MRI to target endomyocardial biopsy as described above. Viral titiers (serologies) are often unhelpful and not routinely ordered in clinical practice.

Prognosis

There are many prognostic factors which can be evaluated in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy.[12] The most important prognostic indicator is a decreased ejection fraction, in addition increased ventricular size and right ventricular dilation are independent indicators of a poor prognosis.

As is in most cases of heart failure a poor NYHA functional class and increased PASP (>35mmHg) are also poor prognostic indicators.

Other findings that infer a poor prognosis are as follows: Maximal O2 uptake of < 12mL/kg / minute on exercise testing, LBBB (left bundle branch block), non sustained ventricular tachycardia, syncope, hyponatremia with a serum sodium less than 135, elevated norepinephrine, ANP (atrial natriuretic peptide) and renin levels (not routinely measured in clinical practice), elevated PCWP (pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) > 18mmHg, low cardiac index < 2.5L/min/m^2.

Treatment

Years ago the statistic was that the majority of patients, particularly those over 55 years of age, died within 3 years of the onset of symptoms (stage 5 of CHF) – and such figures can still be found in many textbooks. The situation has improved dramatically in recent years with drug therapy that can slow down progression and in some cases even improve the heart condition. Death is due to either congestive heart failure or ventricular tachy- or bradyarrhythmias.

Patients are given the standard therapy for heart failure, typically including salt restriction, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, diuretics, and digitalis. Anticoagulants may also be used. Alcohol should be avoided. Artificial pacemakers may be used in patients with intraventricular conduction delay, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in those at risk of arrhythmia. These forms of treatment have been shown to improve symptoms and reduce hospitalization.

In patients with advanced disease who are refractory to medical therapy, cardiac transplantation may be considered.

Reverse remodeling

The progression of heart failure is associated with left ventricular remodeling, which manifests as gradual increases in left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, wall thinning, and a change in chamber geometry to a more spherical, less elongated shape. This process is usually associated with a continuous decline in ejection fraction. The concept of cardiac remodeling was initially developed to describe changes which occur in the days and months following myocardial infarction. It has been extended to cardiomyopathies of non-ischemic origin, such as idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or chronic myocarditis, suggesting common mechanisms for the progression of cardiac dysfunction. Literally, reverse remodeling is the process of reversing the remodeling, or in other words, it is a process of a temporary or a permanent correction of the heart. A 2004 article gives a description of the current therapies that support reverse remodeling and suggests a new approach to the prognosis of cardiomyopathies.[13]

Alternative treatment

Alternative treatments are promoted by some, including food supplements Coenzyme Q10, L-Carnitine, Taurine and D-Ribose, and there is some evidence for the benefits of Coenzyme Q10 in treating heart failure.[14][15][16] The majority of doctors doubt the effectiveness of these alternative treatments, but a few complement conventional treatment by suggesting Coenzyme Q10.

Gross Pathological Findings

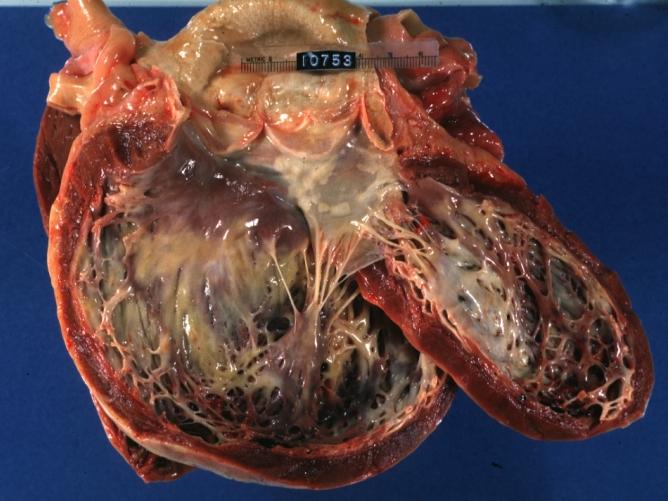

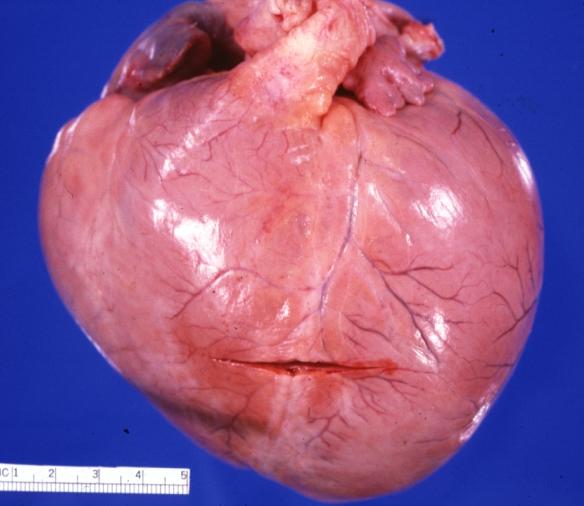

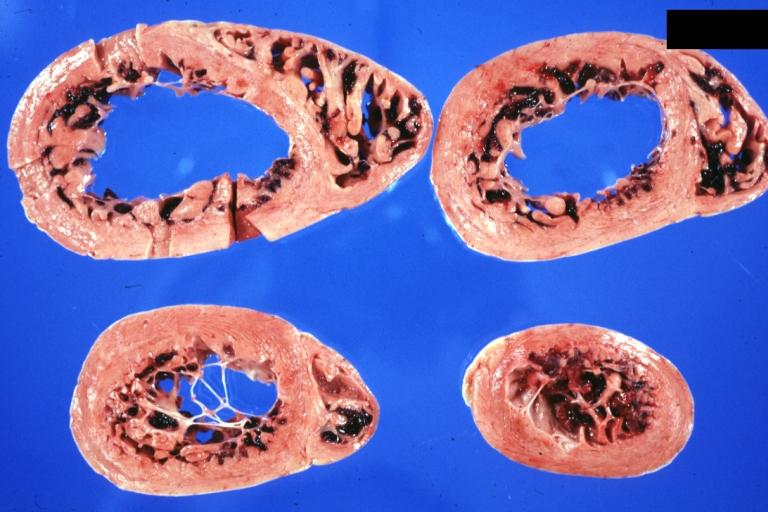

Images shown below are Courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology

-

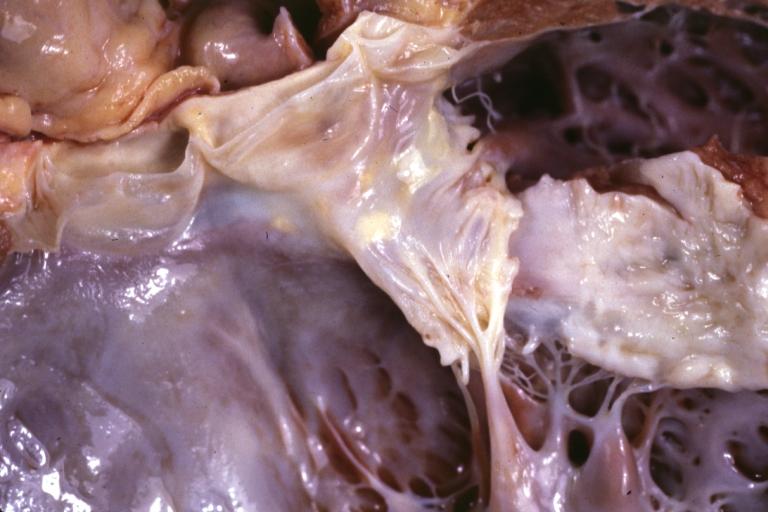

Cardiomyopathy: Gross excellent view of mitral valve from left atrium anterior leaflet appears to balloon a bit into the atrium

-

Cardiomyopathy: Gross excellent view of mitral and tricuspid valves from atria, appear normal anatomy.

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross natural color close-up view of heart surgically removed for a transplantation shows aortic valve and anterior leaflet of mitral valve with cholesterol deposits endocardium of left ventricle is diffusely thickened

-

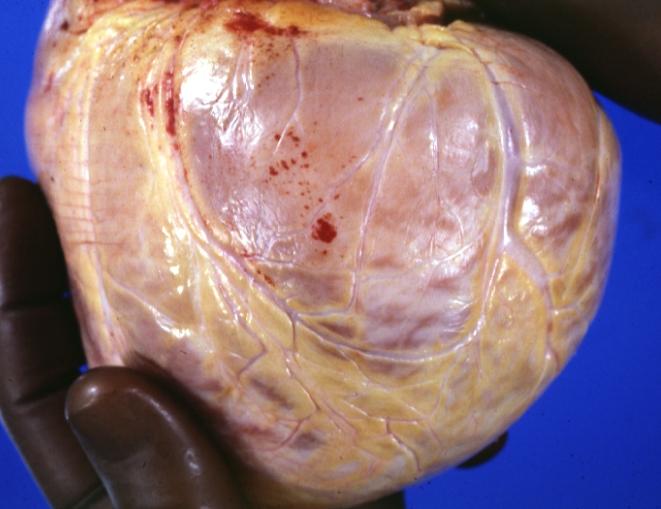

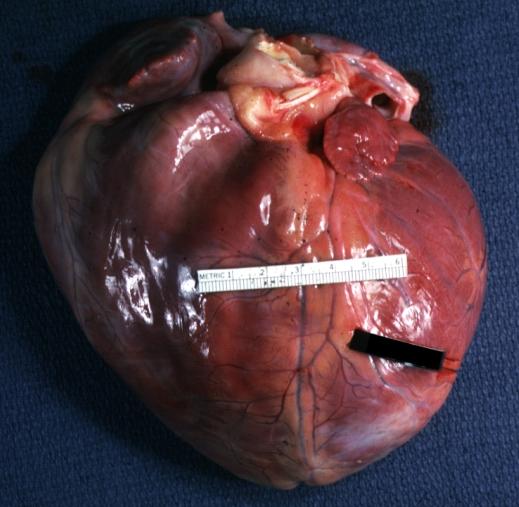

Cardiomyopathy: Gross external view of globular heart with patchy fibrosis seen through epicardium

-

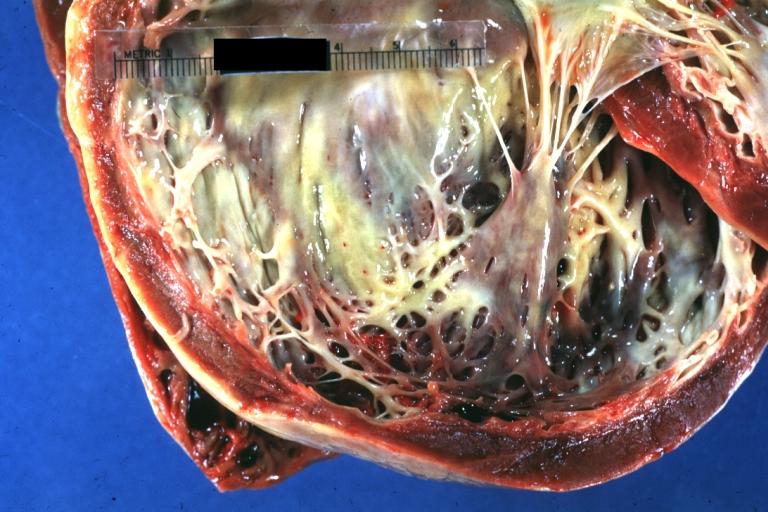

Cardiomyopathy: Gross dilated left ventricle with marked endocardial thickening this is what has been called adult fibroelastosis

-

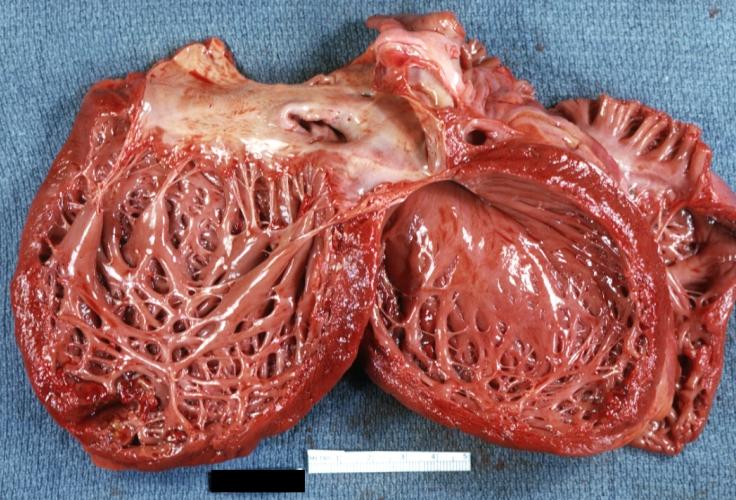

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross good example huge dilated left ventricle

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross dilated left ventricle with marked endocardial sclerosis (an excellent example)

-

Cardiomyopathy: Gross intact globular shaped heart

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross opened left ventricle dilated with endocardial thickening good example

-

Cardiomyopathy: Gross globular heart external view 10 year old girl with sickle cell anemia

-

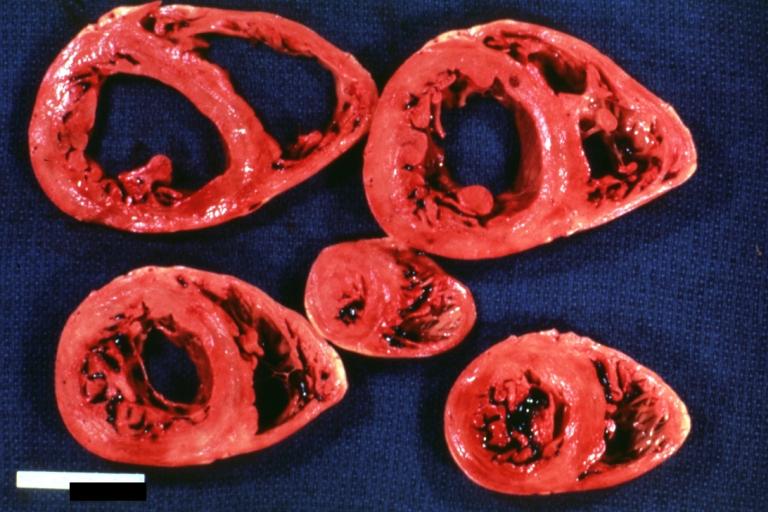

Cardiomyopathy: Gross horizontal sections of ventricles dilation type 10 year old girl with sickle cell anemia

-

Cardiomyopathy: Intermediate between hypertrophic and dilated

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross opened globular left ventricle natural color (very good example)

-

Brain: Infarct: Healing large MCA and PICA probably embolic 64 year old female chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiomyopathy with atrial fibrillation

-

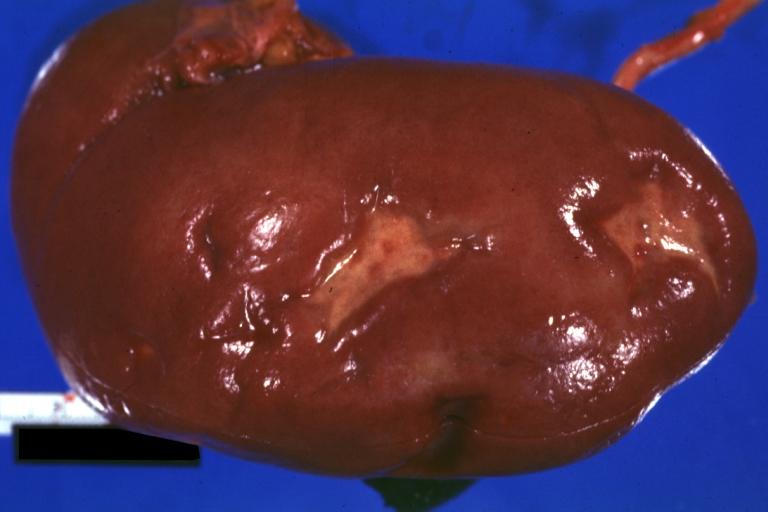

Kidney: Infarct Remote: Gross external view with capsule removed two old and very typical infarct scars 27yobf with dilated cardiomyopathy

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Gross natural color external view globular heart 500 gm 24yo female seven pregnancies

References

- ↑ Dec GW, Fuster V. Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1994 Dec 8;331(23):1564-75. PMID 7969328

- ↑ Robbins Basic Pathology, 7th edition. Kumar, Cotran, Robbins. ISBN 0-7216-9274-5

- ↑ Coughlin SS, Labenberg JR, Tefft MC. Black-white differences in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: the Washington DC Dilated Cardiomyopathy Study. Epidemiology. 1993;4:165-72. PMID 8452906

- ↑ Felker GM, Thompson RE, et al. Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000 Apr 13;342(14):1077-84.

- ↑ Herskowitz A, Ahmed-Ansari A, Neumann DA et al. Induction of major histocompatibility complex antigens within the myocardium of patients with active myocarditis: a nonhistologic marker of myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(3):624-632.

- ↑ Freidrich MG, Strohm O, et al. Contrast media-enhanced mangetic resonance imaging visualizes myocardial changes in the course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1802-1809.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.

- ↑ Ross J Jr. Dilated cardiomyopathy: concepts derived from gene deficient and transgenic animal models. Circ J. 2002;66:219-24. PMID 11922267

- ↑ Mestroni L; Rocco C; et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy: evidence for genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Heart Muscle Disease Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999 Jul;34(1):181-90.

- ↑ Schonberger J, Seidman CE. Many roads lead to a broken heart: the genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:249-60. Epub 2001 Jul 6. PMID 11443548

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Cardiology. Concise Textbook. Murphy, Joseph G; Lloyd, Margaret A. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. 2007.

- ↑ Pieske B. Reverse remodeling in heart failure – fact or fiction? Eur Heart J Suppl. 2004;6:D66-D68. (full text online)

- ↑ Langsjoen PH, Langsjoen PH, Folkers K. A six-year clinical study of therapy of cardiomyopathy with coenzyme Q10. Int J Tissue React. 1990;12:169-71. PMID 2276895

- ↑ Folkers K, Langsjoen P, Langsjoen PH. Therapy with coenzyme Q10 of patients in heart failure who are eligible or ineligible for a transplant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:247-53. PMID 1731784

- ↑ Baggio E, Gandini R, Plancher AC, Passeri M, Carmosino G. Italian multicenter study on the safety and efficacy of coenzyme Q10 as adjunctive therapy in heart failure. CoQ10 Drug Surveillance Investigators. Mol Aspects Med. 1994;15 Suppl:s287-94. PMID 7752841

See Also

External links

Additional Reading

- Moss and Adams' Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents Hugh D. Allen, Arthur J. Moss, David J. Driscoll, Forrest H. Adams, Timothy F. Feltes, Robert E. Shaddy, 2007 ISBN 0781786843

- Braunwald's Heart Disease, Libby P, 8th ed., 2007, ISBN 978-1-41-604105-4

- Hurst's the Heart, Fuster V, 12th ed. 2008, ISBN 978-0-07-149928-6

- Willerson JT, Cardiovascular Medicine, 3rd ed., 2007, ISBN 978-1-84628-188-4