Contrast induced nephropathy primary prevention: Difference between revisions

Rim Halaby (talk | contribs) |

Rim Halaby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

====Statins==== | ====Statins==== | ||

====Fenoldopam | ====Fenoldopam==== | ||

====N-acetylcysteine==== | ====N-acetylcysteine==== | ||

Revision as of 22:59, 3 October 2013

|

Contrast Induced Nephropathy Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Contrast induced nephropathy from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Contrast induced nephropathy primary prevention On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Contrast induced nephropathy primary prevention |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Contrast induced nephropathy |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Contrast induced nephropathy primary prevention |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohamed Moubarak, M.D. [2]

Overview

General measures should be followed to minimize the incidence of CIN, include carefully considering whether the contrast examination is absolutely needed, especially in high-risk patients, using the minimal effective dose, and eliminating potentially nephrotoxic drugs at least 24 hr before the study. Encourage IV hydration and following protocols that allow clear liquids up to 2 hr before the procedure. Alternative diagnostic procedures should be considered in those at high-risk.

Prevention

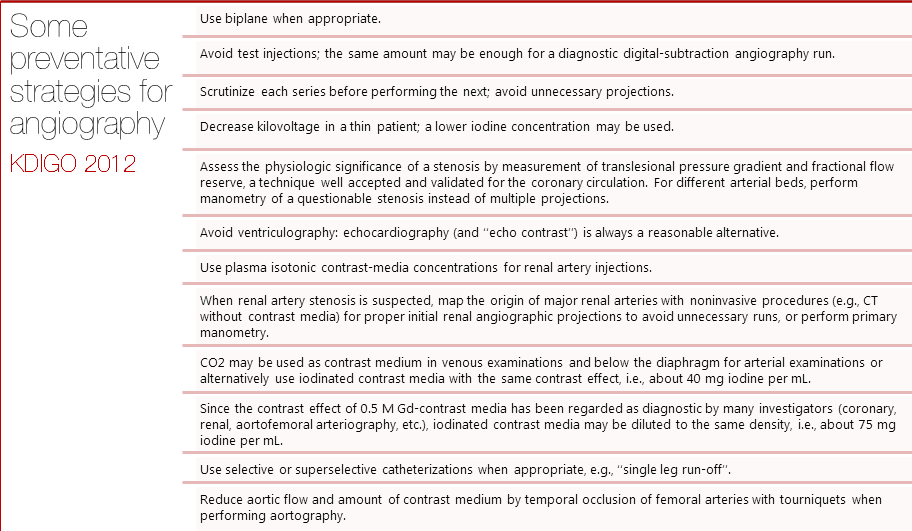

Strategies proposed to prevent the occurrence of CIN have been extensively studied but compelling evidence regarding the implementation of most of these approaches is still lacking. Prophylactic measures were recently defined in the 2012 KDIGO Guidelines and divided broadly into pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches.

Non-Pharmacologic Approaches

Dose of contrast media

It has been shown that larger doses of contrast media are associated with higher risks of CIN. Still, no specific dose recommendations have been made due to lack of robust evidence. The 2012 KDIGO guidelines recommended using the smallest possible dose in every procedure requiring IV contrast especially in patients at high risk for developing CIN.[1] Nyman et al suggested an alternative approach, using the ratio of dose of iodine (in grams) to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The team found the ratio to be predictive of the risk of CIN. A ratio I(g)/eGFR < 1 was shown to be relatively safe even in patients with many possible risk factors. The estimated risk decreased eightfold when the ratio dropped below 1.[2]

Route of Administration

Most studies illustrating the pathophysiology, treatment and prophylaxis of CIN focus on intra-arterial (IA) injection of contrast media considering it has been associated with the highest cases of CIN. A number of trials have also shown that intra-venous (IV) contrast has a significantly lower risk of CIN than IA contrast.[3][4] In fact, a review by Rao and Newhouse showed that in studies with proper controls, the risk of CIN after IV contrast administration did not differ between the study groups and the control groups.[5] This further emphasizes the importance of the route of contrast administration, and points to the fact that IV contrast has not been explicitly shown to be nephrotoxic.

Osmolarity of Contrast Agent

The osmolarity of the contrast medium has been clinically linked to differences in outcome. Initially, small scale studies showed no difference between high-osmolar and low-osmolar contrast media.[6] However, in 1995, a prospective randomized trial by Rudnick et al revealed that patients with renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus had a significantly lower risk of CIN with low-osmolar media.[7] With the introduction of iso-osmolar media, several comparative studies most importantly the NEPHRIC trial by Aspelin et al showed that iso-osmolar media is highly superior in high risk patients with pre-existing renal disease and diabetes. The trial demonstrated that the incidence of CIN in the iso-osmolar contrast group was 3.1% compared with 26.2% in the low-osmolar contrast group.[8] Results of the NEPHRIC trial have sometimes been questioned to the lack of reproducibility in other trials. However, it is generally agreed that iso-osmolar contrast media pose the lowest risk of CIN among other contrast agents. The 2012 KDIGO Guidelines advocated the use of either iso-osmolar or low-osmolar iodinated contrast media, rather than high-osmolar media particularly in patients at increased risk of CIN.[1]

|

|

Pharmacologic Approaches

Volume Expansion

Volume expansion has been shown to significantly decrease the risk of CIN; however, no randomized control trials comparing fluids to placebo have been conducted. Results are extrapolated from comparison with historically untreated patients.[1] The mechanisms by which volume expansion decrease the risk of CIN may include dilution of the contrast media, increase in renal prostaglandins, counteraction of altered renal hemodynamics, and inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system. Many fluids have been investigated for expansion prior to contrast administration including normal saline (0.9%), hypotonic saline (0.45%), and isotonic sodium bicarbonate. Results of the studies comparing these fluids are variable and interpretation is not always easy given the significant limitations of these studies and the many confounding factors not accounted for.

Still, most studies suggest that fluid administration should be initiated 1-2 h before and maintained for 3–6 hours after contrast exposure.[1] Normal saline has been shown to be more effective than hypotonic saline in patients undergoing coronary angiography.[9] Bicarbonate has been suggested to be more efficacious than normal saline via additional benefits through free radical scavenging.[10] However, no robust evidence on the use of bicarbonate has been presented. A thorough meta-analysis of all randomized trials between 1950 and 2008 showed no clear benefit from bicarbonate expansion on the risk of mortality and dialysis.[11] In contrast, acetazolamide in combination with normal saline was found to be more beneficial than bicarbonate alone.[12] Nonetheless, the 2012 KDIGO guidelines did not recommend against the use of bicarbonate stating possible benefit but inconsistent data. They also recommended against the use of oral volume expansion.[1]

Theophylline

Statins

Fenoldopam

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) 600 mg orally twice a day, on the day before and of the procedure if creatinine clearance is estimated to be less than 60 mL/min [1.00 mL/s]) may reduce nephropathy.[13]. A randomized controlled trial found higher doses of NAC (1200-mg IV bolus and 1200 mg orally twice daily for 2 days) benefited (relative risk reduction of 74%) patients receiving coronary angioplasty with higher volumes of contrast[14].

Since publication of the meta-analyses, two small and underpowered negative studies, one of IV NAC[15] and one of 600 mg give four times around coronary angiography[16], found statistically insignificant trends towards benefit.

Some authors believe the benefit is not overwhelming.[17] The strongest results were from an unblinded randomized controlled trial that used NAC intravenously.[18] A systematic review by Clinical Evidence concluded that NAC is "likely to beneficial" but did not recommend a specific dose.[19] One study found that the apparent benefits of NAC may be due to its interference with the creatinine laboratory test itself.[20] This is supported by a lack of correlation between creatinine levels and cystatin C levels.

ACT Trial which is a randomized, placebo controlled trial randomized 2308 patients undergoing angiography with at least one risk factor for contrast induced nephropathy. Patients were randomized to receive either high dose of NAC or placebo on the day before and after the procedure. No difference was noted in rates of developing nephropathy between the two groups[21]. Therefore short-term use of NAC for the prevention of contrast induced nephropathy should be avoided[22].

In a series, 15% of patients receiving NAC intravenously had allergic reactions[18].

Other interventions

Other pharmacological agents, such as furosemide, mannitol, dopamine, and atrial natriuretic peptide have been tried, but have either not had beneficial effects, or had detrimental effects.[23][24]

Choice of contrast agent

The osmolality of the contrast agent has traditionally been believed to be of great importance in contrast-induced nephropathy. Ideally, the contrast agent should be iso-osmolar to blood. Modern iodinated contrast agents are non-ionic.

- Iso-osmolar, nonionic contrast media may be the best according to a randomized controlled trial.[8]

- Hypo-osmolar, non-ionic contrast agents are beneficial if iso-osmolar, nonionic contrast media is not available due to costs.[25]

2012 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury (DO NOT EDIT)[26]

Nonpharmacological prevention strategies of CI-AKI

| Level 1 |

| "1. We recommend using either iso-osmolar or low-osmolar iodinated contrast media, rather than high-osmolar iodinated contrast media in patients at increased risk of CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 1B)" |

| Not Graded |

| "1. Use the lowest possible dose of contrast medium in patients at risk for CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: Not Graded)" |

| Level 2 |

| "1. We suggest not using prophylactic intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) or hemofiltration (HF) for contrast-media removal in patients at increased risk for CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 2C)" |

Pharmacological prevention strategies of CI-AKI

| Level 1 |

| "1. We recommend i.v. volume expansion with either isotonic sodium chloride or sodium bicarbonate solutions, rather than no i.v. volume expansion, in patients at increased risk for CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 1A)" |

| "2. We recommend not using oral fluids alone in patients at increased risk of CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 1C)" |

| "3. We recommend not using fenoldopam to prevent CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 1B)" |

| Level 2 |

| "1. We suggest using oral NAC, together with i.v. iso-tonic crystalloids, in patients at increased risk of CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 2D)" |

| "2. We suggest not using theophylline to prevent CI-AKI. (Level of Evidence: 2C)" |

2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline Recommendations: Pre-procedural Considerations (DO NOT EDIT)[27]

Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury

| Class I |

| "1. Patients should be assessed for risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury before PCI.[28][29] (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "2. Patients undergoing cardiac catheterization with contrast media should receive adequate preparatory hydration.[30][31][23][32] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| "3. In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (creatinine clearance <60 mL/min), the volume of contrast media should be minimized.[33][34][35] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| Class III: Harm |

| "'1. Administration of N-acetyl-L-cysteine is not useful for the prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury.[36][37][38][39][21] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Work Group (2012). "2012 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury". Kidey Int Supp. 2: 69–88. doi:10.1038/kisup.2011.34.

- ↑ Nyman U, Björk J, Aspelin P, Marenzi G (2008). "Contrast medium dose-to-GFR ratio: a measure of systemic exposure to predict contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention". Acta Radiol. 49 (6): 658–67. doi:10.1080/02841850802050762. PMID 18568558.

- ↑ Cramer BC, Parfrey PS, Hutchinson TA, Baran D, Melanson DM, Ethier RE; et al. (1985). "Renal function following infusion of radiologic contrast material. A prospective controlled study". Arch Intern Med. 145 (1): 87–9. PMID 3882071.

- ↑ Heller CA, Knapp J, Halliday J, O'Connell D, Heller RF (1991). "Failure to demonstrate contrast nephrotoxicity". Med J Aust. 155 (5): 329–32. PMID 1895978.

- ↑ Rao QA, Newhouse JH (2006). "Risk of nephropathy after intravenous administration of contrast material: a critical literature analysis". Radiology. 239 (2): 392–7. doi:10.1148/radiol.2392050413. PMID 16543592.

- ↑ Tepel M, Aspelin P, Lameire N (2006). "Contrast-induced nephropathy: a clinical and evidence-based approach". Circulation. 113 (14): 1799–806. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595090. PMID 16606801.

- ↑ Rudnick MR, Goldfarb S, Wexler L, Ludbrook PA, Murphy MJ, Halpern EF; et al. (1995). "Nephrotoxicity of ionic and nonionic contrast media in 1196 patients: a randomized trial. The Iohexol Cooperative Study". Kidney Int. 47 (1): 254–61. PMID 7731155.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Aspelin P, Aubry P, Fransson SG, Strasser R, Willenbrock R, Berg KJ; et al. (2003). "Nephrotoxic effects in high-risk patients undergoing angiography". N Engl J Med. 348 (6): 491–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021833. PMID 12571256.

- ↑ Mueller C, Buerkle G, Buettner HJ, Petersen J, Perruchoud AP, Eriksson U; et al. (2002). "Prevention of contrast media-associated nephropathy: randomized comparison of 2 hydration regimens in 1620 patients undergoing coronary angioplasty". Arch Intern Med. 162 (3): 329–36. PMID 11822926 Check

|pmid=value (help). Review in: ACP J Club. 2002 Sep-Oct;137(2):44 - ↑ Caulfield JL, Singh SP, Wishnok JS, Deen WM, Tannenbaum SR (1996). "Bicarbonate inhibits N-nitrosation in oxygenated nitric oxide solutions". J Biol Chem. 271 (42): 25859–63. PMID 8824217 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Zoungas S, Ninomiya T, Huxley R, Cass A, Jardine M, Gallagher M; et al. (2009). "Systematic review: sodium bicarbonate treatment regimens for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy". Ann Intern Med. 151 (9): 631–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-9-200911030-00008. PMID 19884624. Review in: Ann Intern Med. 2010 May 18;152(10):JC5-10

- ↑ Assadi F (2006). "Acetazolamide for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy: a new use for an old drug". Pediatr Cardiol. 27 (2): 238–42. doi:10.1007/s00246-005-1132-z. PMID 16391986.

- ↑ Kay J, Chow W, Chan T, Lo S, Kwok O, Yip A, Fan K, Lee C, Lam W (2003). "Acetylcysteine for prevention of acute deterioration of renal function following elective coronary angiography and intervention: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 289 (5): 553–8. PMID 12578487.

- ↑ Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Marana I, Lauri G, Campodonico J, Grazi M, De Metrio M, Galli S, Fabbiocchi F, Montorsi P, Veglia F, Bartorelli A (2006). "N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy in primary angioplasty". N Engl J Med. 354 (26): 2773–82. PMID 16807414.

- ↑ Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Bagshaw SM; et al. (2007). "Phase II, randomized, controlled trial of high-dose N-acetylcysteine in high-risk cardiac surgery patients". Crit. Care Med. 35 (5): 1324–31. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000261887.69976.12. PMID 17414730.

- ↑ Seyon RA, Jensen LA, Ferguson IA, Williams RG (2007). "Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine and hydration versus placebo and hydration in decreasing contrast-induced renal dysfunction in patients undergoing coronary angiography with or without concomitant percutaneous coronary intervention". Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 36 (3): 195–204. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.08.004. PMID 17509426.

- ↑ Gleeson TG, Bulugahapitiya S (2004). "Contrast-induced nephropathy". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 183 (6): 1673–89. PMID 15547209.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Baker CS, Wragg A, Kumar S, De Palma R, Baker LR, Knight CJ (2003). "A rapid protocol for the prevention of contrast-induced renal dysfunction: the RAPPID study". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41 (12): 2114–8. PMID 12821233.

- ↑ Kellum J, Leblanc M, Venkataraman R (2006). "Renal failure (acute)". Clinical evidence (15): 1191–212. PMID 16973048.

- ↑ Hoffmann U, Fischereder M, Kruger B, Drobnik W, Kramer BK (2004). "The value of N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of radiocontrast agent-induced nephropathy seems questionable". J Am Soc Nephrol. 15 (2): 407–10. PMID 14747387.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 ACT Investigators (2011). "Acetylcysteine for Prevention of Renal Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Coronary and Peripheral Vascular Angiography: Main Results From the Randomized Acetylcysteine for Contrast-Induced Nephropathy Trial (ACT)". Circulation. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038943. PMID 21859972.

- ↑ http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/124/11/1210.full

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Solomon R, Werner C, Mann D, D'Elia J, Silva P (1994). "Effects of saline, mannitol, and furosemide to prevent acute decreases in renal function induced by radiocontrast agents". The New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (21): 1416–20. doi:10.1056/NEJM199411243312104. PMID 7969280. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Abizaid AS, Clark CE, Mintz GS, Dosa S, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Harvey M, Kent KM, Leon MB (1999). "Effects of dopamine and aminophylline on contrast-induced acute renal failure after coronary angioplasty in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency". Am J Cardiol. 83 (2): 260–3, A5. PMID 10073832.

- ↑ Schwab S, Hlatky M, Pieper K, Davidson C, Morris K, Skelton T, Bashore T (1989). "Contrast nephrotoxicity: a randomized controlled trial of a nonionic and an ionic radiographic contrast agent". N Engl J Med. 320 (3): 149–53. PMID 2643042.

- ↑ Schmoldt A, Benthe HF, Haberland G (1975). "Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes". Biochem Pharmacol. 24 (17): 1639–41. PMID doi:10.1038/kisup.2011.34 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B; et al. (2011). "2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions". Circulation. 124 (23): e574–651. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. PMID 22064601.

- ↑ Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, Fahy M, Mintz GS, Lansky AJ, Moses JW, Stone GW, Leon MB, Dangas G (2004). "A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 44 (7): 1393–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.068. PMID 15464318. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Moscucci M, Rogers EK, Montoye C, Smith DE, Share D, O'Donnell M, Maxwell-Eward A, Meengs WL, De Franco AC, Patel K, McNamara R, McGinnity JG, Jani SM, Khanal S, Eagle KA (2006). "Association of a continuous quality improvement initiative with practice and outcome variations of contemporary percutaneous coronary interventions". Circulation. 113 (6): 814–22. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541995. PMID 16461821. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Bader BD, Berger ED, Heede MB, Silberbaur I, Duda S, Risler T, Erley CM (2004). "What is the best hydration regimen to prevent contrast media-induced nephrotoxicity?". Clinical Nephrology. 62 (1): 1–7. PMID 15267006. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Mueller C, Buerkle G, Buettner HJ, Petersen J, Perruchoud AP, Eriksson U, Marsch S, Roskamm H (2002). "Prevention of contrast media-associated nephropathy: randomized comparison of 2 hydration regimens in 1620 patients undergoing coronary angioplasty". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (3): 329–36. PMID 11822926. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Trivedi HS, Moore H, Nasr S, Aggarwal K, Agrawal A, Goel P, Hewett J (2003). "A randomized prospective trial to assess the role of saline hydration on the development of contrast nephrotoxicity". Nephron. Clinical Practice. 93 (1): C29–34. PMID 12411756. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, Lauri G, Marana I, De Metrio M, Moltrasio M, Grazi M, Rubino M, Veglia F, Fabbiocchi F, Bartorelli AL (2009). "Contrast volume during primary percutaneous coronary intervention and subsequent contrast-induced nephropathy and mortality". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (3): 170–7. PMID 19189906. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O'Neill WW (1997). "Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality". The American Journal of Medicine. 103 (5): 368–75. PMID 9375704. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Russo D, Minutolo R, Cianciaruso B, Memoli B, Conte G, De Nicola L (1995). "Early effects of contrast media on renal hemodynamics and tubular function in chronic renal failure". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 6 (5): 1451–8. PMID 8589322. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gonzales DA, Norsworthy KJ, Kern SJ, Banks S, Sieving PC, Star RA, Natanson C, Danner RL (2007). "A meta-analysis of N-acetylcysteine in contrast-induced nephrotoxicity: unsupervised clustering to resolve heterogeneity". BMC Medicine. 5: 32. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-5-32. PMC 2200657. PMID 18001477. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ↑ Ozcan EE, Guneri S, Akdeniz B, Akyildiz IZ, Senaslan O, Baris N, Aslan O, Badak O (2007). "Sodium bicarbonate, N-acetylcysteine, and saline for prevention of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy. A comparison of 3 regimens for protecting contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing coronary procedures. A single-center prospective controlled trial". American Heart Journal. 154 (3): 539–44. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.05.012. PMID 17719303. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Thiele H, Hildebrand L, Schirdewahn C, Eitel I, Adams V, Fuernau G, Erbs S, Linke A, Diederich KW, Nowak M, Desch S, Gutberlet M, Schuler G (2010). "Impact of high-dose N-acetylcysteine versus placebo on contrast-induced nephropathy and myocardial reperfusion injury in unselected patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The LIPSIA-N-ACC (Prospective, Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Leipzig Immediate PercutaneouS Coronary Intervention Acute Myocardial Infarction N-ACC) Trial". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 55 (20): 2201–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.091. PMID 20466200. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Webb JG, Pate GE, Humphries KH, Buller CE, Shalansky S, Al Shamari A, Sutander A, Williams T, Fox RS, Levin A (2004). "A randomized controlled trial of intravenous N-acetylcysteine for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy after cardiac catheterization: lack of effect". American Heart Journal. 148 (3): 422–9. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.041. PMID 15389228. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)