Contrast induced nephropathy pathophysiology

|

Contrast Induced Nephropathy Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Contrast induced nephropathy from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Contrast induced nephropathy pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Contrast induced nephropathy pathophysiology |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Contrast induced nephropathy |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Contrast induced nephropathy pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohamed Moubarak, M.D. [2]

Overview

The pathophysiology of CIN is not clearly understood; however, several attempts have been made to explain the underlying mechanism. It is generally agreed that CIN is due to a combination of several influences brought on by contrast-media infusion rather than a single process. The most important mechanism thought to be involved in CIN is a reduction in renal perfusion and subsequent hypoxia. This has been attributed to several alterations in the renal microenvironment including activation of the tubuloglomerular feeback, local vasoactive metabolites including adenosine, prostaglandin, NO, and endothelin as well as increased interstitial pressure.[1] Although sometimes considered controversial, studies have also proposed injury to renal tubular cells as another contributor both via a direct cytotoxic effect and via reactive oxygen species production.[2]

Pathophysiology

Several mechanisms have been put forth to explain the development of nephropathy following contrast administration. Broadly, the pathophysiology can be divided into renal vascular compromise and cytotoxic tubular cell injury.

Renal Vascular Compromise and Hypoxia

Vascular Resistance

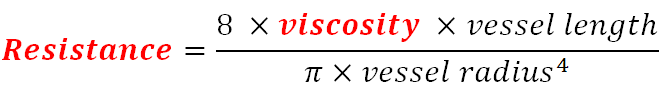

The renal vascular bed is supplied by small capillaries known as the vasa recta. While these small vessels have a diameter similar to that of other capillaries, their length is usually several times longer, creating higher vascular resistance. To offset that, viscosity needs to be maintained at its lowest demonstrated in Poiseuille’s law:

Several rat models have shown association between plasma viscosity, increased vascular resistance, and contrast-media infusion. As viscosity increases, resistance in the vasa recta can rise to cause significant renal tissue hypoperfusion[2] Some agents have an inherently higher viscosity leading to higher resistance while others can interact with red blood cells causing a decrease in deformability and a secondary increase in resistance.[3]

Increased viscosity also transfers to tubular fluid which is usually low in proteins and less viscous than plasma. Some models have shown that as urine concentration occurs in the tubules, viscosity increases significantly in the renal tubules leading to an increase in renal interstitial pressure.[4][5] The rising pressure further increases vasa recta hypoperfusion and also contributing to hypoxia.

Tubuloglomerular Feedback

The tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) describes the function of the macula densa, a dense collection of specialized epithelial cells at the junction of the thick ascending loop and the distal convoluted tubule. The macula densa senses sodium delivery to the distal tubules via a Na+/K+/2Cl- transporter. High sodium delivery is perceived as high glomerular filtration which causes adenosine release from the macula densa and vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole to decrease filtration.[6] The osmotic diuresis theory hypothesizes that contrast media cause increased natriuresis and thus activate TGF leading to vasoconstriction. This theory has been challenged multiple times and studies have shown little or no effect of the TGF on CIN. Tangibly, the use of furosemide, a Na+/K+/2Cl- transporter blocker, was not shown to significantly prevent CIN after cardiac angiography.[7]

Vasoconstriction and Vasoactive Substances

Initial animal studies showed that contrast media infusion causes a biphasic vascular response. With early infusion, a short phase of renal vasodilation arises followed by a prolonged phase of vasoconstriction eventually leading to tissue hypoxia.[8] Several studies have tried to explain the mechanism underlying the vasoconstrictive phase with common emphasis on an imbalance of vasoactive substances brought on by the contrast media.

- Adenosine

Adenosine is a byproduct of ATP metabolism responsible for certain alterations in renal hemodynamics. It's most important role is in the tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) but has other functions dependening on receptor subtype.[9] The renal vasculature has 2 main classes of adenosine receptors: A1 and A2. The A1 receptor is found in high concentrations in the afferent arteriole and glomerular mesangium mediating vasoconstriction and mesangial contraction respectively. The A2 receptor is more widely distributed and mediates vasodilation usually enhancing renal medullary blood flow.[10] Adenosine has been proposed as a mediator of vasoconstriction following contrast infusion but a number of studies have shown that it's role may be overestimated in CIN. It was shown that in renal insufficiency models adenosine may play role in hypoperfusion. This may be attributed to the baseline requirements of the diseased kidney and that activation of the A1 receptors may be detrimental to renal function.[11] However, blocking A1 receptors in rats prior to contrast injection did not appear to decrease medullary hypoperfusion.[12] It was also shown that the decrease in GFR and overall reduction in renal plasma flow cannot be attributed to adenosine activity alone.[13]

- Endothelin

Endothelin is a peptide released from endothelial cells mediating vasoconstriction or vasodilation depending on the vascular bed and the receptors in question. Broadly ET-A receptors mediate vasoconstriction while ET-B receptors mediate vasodilation. It has been postulated that an endothelin response to contrast media is responsible for CIN. Several studies have also shown increased endothelin levels in the urine and plasma after contrast exposure.[14] However, Wang et al showed that blocking both ET-A and ET-B receptors in people before exposure to contrast media increased the risk of CIN.[15] This may be in part correlated to the blunting of the effect of ET-B responsible for vasodilation as well as the inhibition of the negative feedback loop initiated by ET-B that decreases endothelin secretion.[16] Investigation into a selective ET-A receptor antagonist is underway, with initial animal studies showing some promise.[17]

Hypoxia

Renal cortical perfusion is usually very high. However, the renal medulla, particularly the deeper potion of the outer medulla, is maintained at very low PO2levels that can reach 20 mm Hg. This area is relatively distant from the vasa recta often being the first to be damaged in hypoxic injury.[18] Although contrast media induce medullary hypoperfusion possibly via vasoconstriction, they also and increased work-load for tubular cells exacerbating the already existing hypoxic conditions by increasing oxygen consumption.[2]

Cytotoxic Effects of Contrast Media

Contrast media have been implicated in direct and indirect cytotoxic effects on renal tubular cells.

Effect of Contrast Osmolarity

Previously regarded as the main mechanism of renal injury, osmotic stress was not substantiated as a strong component especially when contrast media were compared to other substances with high osmolarity namely mannitol.[19] Still, although the proposed mechanism for the osmotic theory could not be verified, osmolarity of the contrast medium has been clinically linked to differences in outcome. Initially, small scale studies showed no difference between high-osmolar and low-osmolar contrast media.[20] However, in 1995, a prospective randomized trial by Rudnick et al revealed that patients with renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus had a significantly lower risk of CIN with low-osmolar media.[21] With the introduction of iso-osmolar media, several comparative studies most importantly the NEPHRIC trial by Aspelin et al showed that iso-osmolar media is highly superior in high risk patients with pre-existing renal disease and diabetes. The trial demonstrated that the incidence of CIN in the iso-osmolar contrast group was 3.1% compared with 26.2% in the low-osmolar contrast group.[22] Results of the NEPHRIC trial have sometimes been questioned to the lack of reproducibility in other trials. However, it is generally agreed that iso-osmolar contrast media pose the lowest risk of CIN among other contrast agents. Despite those findings, the underlying mechanism linking osmolarity to CIN is still poorly understood.

Reactive Oxygen Species

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are normally produced in baseline conditions but increase drastically during oxidative stress. The most commonly produced ROS species are hydroxy radical (OH-), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and superoxide anion (O2-).[23] In models investigating diabetic nephropathy, excessive ROS were associated with a decrease in NO and subsequent blunting of vasodilation leading to renal hypoperfusion.[24] Similarly for CIN, human and animal experiments that tried reducing the hypothesized ROS load caused by contrast media have shown attenuated reductions in GFR and a lower risk of CIN.[25][26] This underlines the interest in targeting ROS as a treatment for CIN with several antioxidants already investigated in the treatment of CIN.

Renal Toxicity of Gadolinium

The administration of gadolinium-based contrast media among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) has long been considered safe as compared to iodinated contrast media. Nevertheless, reports about the renal toxicity of gadolinium describe mixed results. While earlier articles report the safety of gadolinium-based contrast media,[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] others demonstrate that gadolinium-based contrast media is not as safe as it is thought among patients with CKD.[35][36][37][38] This discrepancy in results might be explained by the lack of randomization, the different dosages of gadolinium that was administered, and the small number of patients in most of the studies.

In a study of 25 patients with CKD (GFR ≤40 mL/min.1.73m2), 28 % of the patients developed CIN (defined as increase in serum creatinine by > 0.5 mg/dL within 48 hours) following the administration of gadolinium-based contrast media compared to 6.5% in those who received iodinated contrast media.[35] In another retrospective study of 91 patients with GFR ranging from 15 to 59 mL/min.1.73m2, the administration of 0.2 ml/kg of gadolinium based contrast lead to CIN in 12.1% of patients.[36] Another study reports that out of 195 CKD patients who received gadolinium, nephrotoxicity occurred in 3.5% of the patients among whom creatinine clearance ranged from 9 to 61 mL/min.1.73m2.[39] In addition, 5 out of 10 patients with a GRF <50 mL/min.1.73m2 (mean GFR of 32 mL/min.1.73m2) in another study developed gadolinium associated nephrotoxicity.[38]

References

- ↑ Wong PC, Li Z, Guo J, Zhang A (2012). "Pathophysiology of contrast-induced nephropathy". Int J Cardiol. 158 (2): 186–92. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.115. PMID 21784541.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Persson PB, Hansell P, Liss P (2005). "Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy". Kidney Int. 68 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00377.x. PMID 15954892.

- ↑ Schiantarelli P, Peroni F, Tirone P, Rosati G (1973). "Effects of iodinated contrast media on erythrocytes. I. Effects of canine erythrocytes on morphology". Invest Radiol. 8 (4): 199–204. PMID 4724805.

- ↑ Ueda J, Nygren A, Hansell P, Erikson U (1992). "Influence of contrast media on single nephron glomerular filtration rate in rat kidney. A comparison between diatrizoate, iohexol, ioxaglate, and iotrolan". Acta Radiol. 33 (6): 596–9. PMID 1449888.

- ↑ Ueda J, Nygren A, Hansell P, Ulfendahl HR (1993). "Effect of intravenous contrast media on proximal and distal tubular hydrostatic pressure in the rat kidney". Acta Radiol. 34 (1): 83–7. PMID 8427755.

- ↑ Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, Roman RJ (2013). "Molecular Mechanisms of Renal Blood Flow Autoregulation". Curr Vasc Pharmacol. PMID 24066938.

- ↑ Solomon R, Werner C, Mann D, D'Elia J, Silva P (1994). "Effects of saline, mannitol, and furosemide to prevent acute decreases in renal function induced by radiocontrast agents". N Engl J Med. 331 (21): 1416–20. doi:10.1056/NEJM199411243312104. PMID 7969280.

- ↑ Bakris GL, Burnett JC (1985). "A role for calcium in radiocontrast-induced reductions in renal hemodynamics". Kidney Int. 27 (2): 465–8. PMID 2581011.

- ↑ Weihprecht H, Lorenz JN, Briggs JP, Schnermann J (1992). "Vasomotor effects of purinergic agonists in isolated rabbit afferent arterioles". Am J Physiol. 263 (6 Pt 2): F1026–33. PMID 1481880.

- ↑ Spielman WS, Arend LJ (1991). "Adenosine receptors and signaling in the kidney". Hypertension. 17 (2): 117–30. PMID 1991645.

- ↑ Arakawa K, Suzuki H, Naitoh M, Matsumoto A, Hayashi K, Matsuda H; et al. (1996). "Role of adenosine in the renal responses to contrast medium". Kidney Int. 49 (5): 1199–206. PMID 8731082.

- ↑ Liss P, Carlsson PO, Palm F, Hansell P (2004). "Adenosine A1 receptors in contrast media-induced renal dysfunction in the normal rat". Eur Radiol. 14 (7): 1297–302. doi:10.1007/s00330-003-2167-2. PMID 14714138.

- ↑ Oldroyd SD, Fang L, Haylor JL, Yates MS, El Nahas AM, Morcos SK (2000). "Effects of adenosine receptor antagonists on the responses to contrast media in the isolated rat kidney". Clin Sci (Lond). 98 (3): 303–11. PMID 10677389.

- ↑ Clark BA, Kim D, Epstein FH (1997). "Endothelin and atrial natriuretic peptide levels following radiocontrast exposure in humans". Am J Kidney Dis. 30 (1): 82–6. PMID 9214405.

- ↑ Wang A, Holcslaw T, Bashore TM, Freed MI, Miller D, Rudnick MR; et al. (2000). "Exacerbation of radiocontrast nephrotoxicity by endothelin receptor antagonism". Kidney Int. 57 (4): 1675–80. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00012.x. PMID 10760103.

- ↑ Haylor JL, Morcos SK (2001). "An oral ET(A)-selective endothelin receptor antagonist for contrast nephropathy?". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 16 (7): 1336–7. PMID 11427621.

- ↑ Pollock DM, Polakowski JS, Wegner CD, Opgenorth TJ (1997). "Beneficial effect of ETA receptor blockade in a rat model of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy". Ren Fail. 19 (6): 753–61. PMID 9415932.

- ↑ Brezis M, Rosen S (1995). "Hypoxia of the renal medulla--its implications for disease". N Engl J Med. 332 (10): 647–55. doi:10.1056/NEJM199503093321006. PMID 7845430.

- ↑ Hardiek K, Katholi RE, Ramkumar V, Deitrick C (2001). "Proximal tubule cell response to radiographic contrast media". Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 280 (1): F61–70. PMID 11133515.

- ↑ Tepel M, Aspelin P, Lameire N (2006). "Contrast-induced nephropathy: a clinical and evidence-based approach". Circulation. 113 (14): 1799–806. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595090. PMID 16606801.

- ↑ Rudnick MR, Goldfarb S, Wexler L, Ludbrook PA, Murphy MJ, Halpern EF; et al. (1995). "Nephrotoxicity of ionic and nonionic contrast media in 1196 patients: a randomized trial. The Iohexol Cooperative Study". Kidney Int. 47 (1): 254–61. PMID 7731155.

- ↑ Aspelin P, Aubry P, Fransson SG, Strasser R, Willenbrock R, Berg KJ; et al. (2003). "Nephrotoxic effects in high-risk patients undergoing angiography". N Engl J Med. 348 (6): 491–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021833. PMID 12571256.

- ↑ Schnackenberg CG (2002). "Physiological and pathophysiological roles of oxygen radicals in the renal microvasculature". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 282 (2): R335–42. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00605.2001. PMID 11792641.

- ↑ Ishii N, Patel KP, Lane PH, Taylor T, Bian K, Murad F; et al. (2001). "Nitric oxide synthesis and oxidative stress in the renal cortex of rats with diabetes mellitus". J Am Soc Nephrol. 12 (8): 1630–9. PMID 11461935.

- ↑ Bakris GL, Lass N, Gaber AO, Jones JD, Burnett JC (1990). "Radiocontrast medium-induced declines in renal function: a role for oxygen free radicals". Am J Physiol. 258 (1 Pt 2): F115–20. PMID 2301588.

- ↑ Katholi RE, Woods WT, Taylor GJ, Deitrick CL, Womack KA, Katholi CR; et al. (1998). "Oxygen free radicals and contrast nephropathy". Am J Kidney Dis. 32 (1): 64–71. PMID 9669426.

- ↑ Bellin MF, Deray G, Assogba U, Auberton E, Ghany F, Dion-Voirin E; et al. (1992). "Gd-DOTA: evaluation of its renal tolerance in patients with chronic renal failure". Magn Reson Imaging. 10 (1): 115–8. PMID 1545669.

- ↑ Hammer FD, Malaise J, Goffette PP, Mathurin P (2000). "Gadolinium dimeglumine: an alternative contrast agent for digital subtraction angiography in patients with renal failure". Transplant Proc. 32 (2): 432–3. PMID 10715468.

- ↑ Kaufman JA, Geller SC, Bazari H, Waltman AC (1999). "Gadolinium-based contrast agents as an alternative at vena cavography in patients with renal insufficiency--early experience". Radiology. 212 (1): 280–4. doi:10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl15280. PMID 10405754.

- ↑ Bacon CR, Davenport AP (1996). "Endothelin receptors in human coronary artery and aorta". Br J Pharmacol. 117 (5): 986–92. PMC 1909397. PMID 8851522.

- ↑ Rieger J, Sitter T, Toepfer M, Linsenmaier U, Pfeifer KJ, Schiffl H (2002). "Gadolinium as an alternative contrast agent for diagnostic and interventional angiographic procedures in patients with impaired renal function". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 17 (5): 824–8. PMID 11981070.

- ↑ Rofsky NM, Weinreb JC, Bosniak MA, Libes RB, Birnbaum BA (1991). "Renal lesion characterization with gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging: efficacy and safety in patients with renal insufficiency". Radiology. 180 (1): 85–9. doi:10.1148/radiology.180.1.2052729. PMID 2052729.

- ↑ Sancak T, Bilgic S, Sanldilek U (2002). "Gadodiamide as an alternative contrast agent in intravenous digital subtraction angiography and interventional procedures of the upper extremity veins". Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 25 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1007/s00270-001-0083-x. PMID 11907774.

- ↑ Spinosa DJ, Angle JF, Hagspiel KD, Kern JA, Hartwell GD, Matsumoto AH (2000). "Lower extremity arteriography with use of iodinated contrast material or gadodiamide to supplement CO2 angiography in patients with renal insufficiency". J Vasc Interv Radiol. 11 (1): 35–43. PMID 10693711.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Briguori C, Colombo A, Airoldi F, Melzi G, Michev I, Carlino M; et al. (2006). "Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrotoxicity in patients undergoing coronary artery procedures". Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 67 (2): 175–80. doi:10.1002/ccd.20592. PMID 16400668.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Ergün I, Keven K, Uruç I, Ekmekçi Y, Canbakan B, Erden I; et al. (2006). "The safety of gadolinium in patients with stage 3 and 4 renal failure". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 21 (3): 697–700. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi304. PMID 16326736.

- ↑ Lima AA, Guerrant RL (1992). "Persistent diarrhea in children: epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, nutritional impact, and management". Epidemiol Rev. 14: 222–42. PMID 1289113.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Erley CM, Bader BD, Berger ED, Tuncel N, Winkler S, Tepe G; et al. (2004). "Gadolinium-based contrast media compared with iodinated media for digital subtraction angiography in azotaemic patients". Nephrol Dial Transplant. 19 (10): 2526–31. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh272. PMID 15280530.

- ↑ Sam AD, Morasch MD, Collins J, Song G, Chen R, Pereles FS (2003). "Safety of gadolinium contrast angiography in patients with chronic renal insufficiency". J Vasc Surg. 38 (2): 313–8. PMID 12891113.