Addison's disease pathophysiology

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6XcBp8EV7Q%7C350}} |

|

Addison's disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Addison's disease pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Addison's disease pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Addison's disease pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aditya Ganti M.B.B.S. [2]

Overview

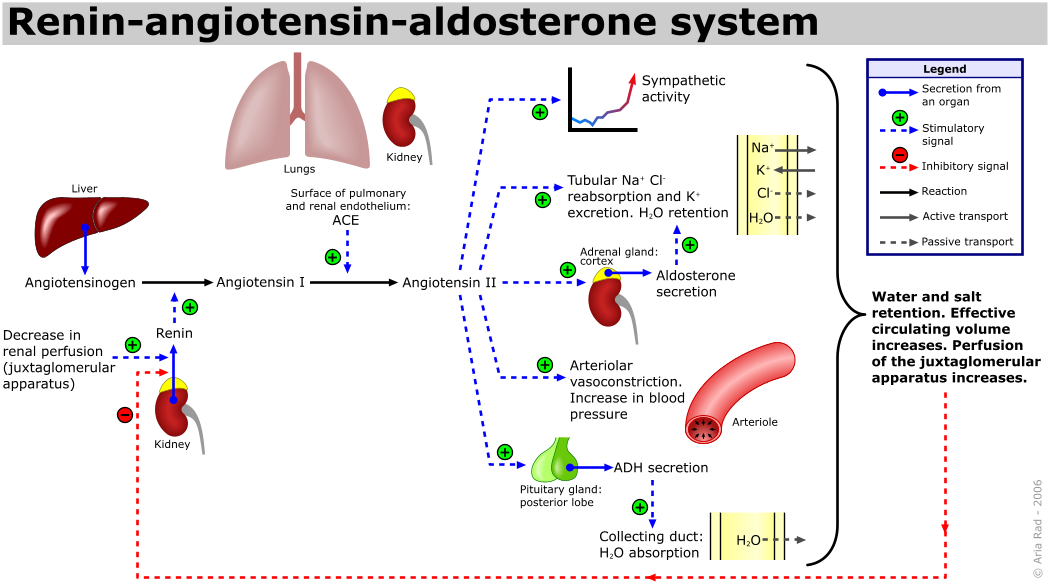

The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to release corticotropin (ACTH). ACTH travels via the blood to the adrenal gland, where it stimulates the release of cortisol. Cortisol is secreted by the cortex of the adrenal gland from a region called the zona fasciculata in response to ACTH. Elevated levels of cortisol exert negative feedback on the pituitary, which decreases the amount of ACTH released from the pituitary gland. When the adrenal glands do not produce enough of the hormone cortisol and aldosterone it results in Addison's disease.

Normal Physiology of Adrenal Glands

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

- The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, secrete corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

- It stimulates the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

- ACTH, in turn, acts on the adrenal cortex, which produces glucocorticoid hormones (mainly cortisol in humans) in response to stimulation by ACTH.

- Glucocorticoids in turn act back on the hypothalamus and pituitary (to suppress CRH and ACTH production) in a negative feedback cycle.

Cortisol

| Harmone | Type of class | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Glucocorticoids |

|

| Aldosterone | Mineralocorticoids |

|

Pathophysiology

Addison's disease occurs when the adrenal glands do not produce enough of the hormone cortisol and, in some cases, the hormone aldosterone. Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be grouped by the way in which they cause the adrenals to produce insufficient cortisol. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol) or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to the gland being damaged).

| Causes | Definition | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| Adrenal dysgenesis | Gland has not formed adequately during development |

|

| Impaired steroidogenesis |

|

|

| Adrenal destruction |

|

|

Genetics

- Hereditary factors sometimes play a key role in the development of autoimmune adrenal insufficiency.[1]

- Common genetic conditions associated with addison's diseases include:

- Familial glucocorticoid insufficiency may be associated with a recessive gene pattern.

- Adrenomyeloneuropathy is known to be X-linked

- Addison disease is associated with a variety of autoimmune conditions that have been linked to genetic factors.

- Patients with autoimmune polyglandular failure might develop diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, and hypothyroidism secondary to antibodies which develop in adrenal glands.

Associated conditions

Addison's disease is commonly seen associated with conditions such as:

- Autoimmune hypoparathyroidism resulting in hypocalcemia

- Vitiligo

- Premature ovarian failure

- Pernicious anemia

- Myasthenia gravis

- Chronic candidiasis

- Sjögren syndrome

- Chronic active hepatitis

- Diabetes mellitus type 1

- Hypothyroidism

- Hashimoto thyroiditis

- Graves hyperthyroidism

- Adrenoleukodystrophy

References

- ↑ Michels AW, Eisenbarth GS (2010). "Immunologic endocrine disorders". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125 (2 Suppl 2): S226–37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.053. PMC 2835296. PMID 20176260.