ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms

|

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction Microchapters |

|

Differentiating ST elevation myocardial infarction from other Diseases |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

|

Case Studies |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms On the Web |

|

FDA on ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms |

|

CDC on ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms in the news |

|

Blogs on ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating ST elevation myocardial infarction |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for ST elevation myocardial infarction history and symptoms |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

The onset of symptoms in myocardial infarction (MI) is usually gradual, over several minutes, and rarely instantaneous.[1]

Symptoms

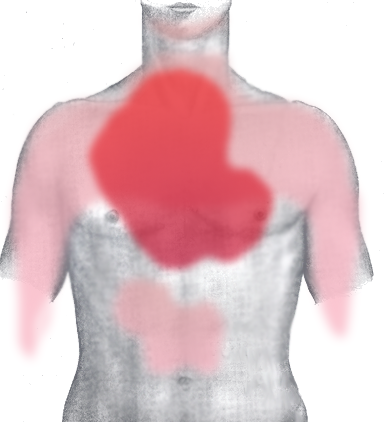

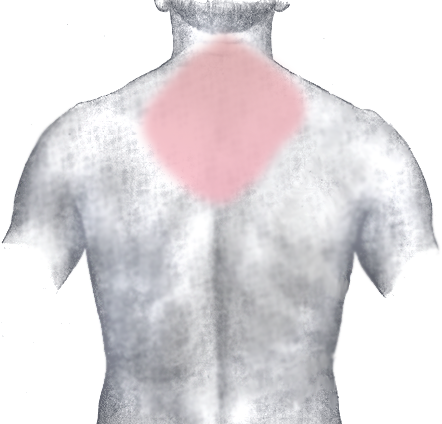

Chest pain is the most common symptom of acute myocardial infarction and is often described as a sensation of tightness, pressure, or squeezing. Chest pain due to ischemia (a lack of blood and hence oxygen supply) of the heart muscle is termed angina pectoris. Pain radiates most often to the left arm, but may also radiate to the lower jaw, neck, right arm, back, and epigastrium, where it may mimic heartburn. Any group of symptoms compatible with a sudden interruption of the blood flow to the heart are called an acute coronary syndrome.[2] Other conditions such as aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism may present with chest pain and must be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) occurs when the damage to the heart limits the output of the left ventricle, causing left ventricular failure and consequent pulmonary edema. Other symptoms include diaphoresis (an excessive form of sweating), weakness, light-headedness, nausea, vomiting, and palpitations. Loss of consciousness and even sudden death can occur in myocardial infarctions.

Women often experience markedly different symptoms than men. The most common symptoms of MI in women include dyspnea, weakness, and fatigue. Fatigue, sleep disturbances, and dyspnea have been reported as frequently occurring symptoms which may manifest as long as one month before the actual clinically manifested ischemic event. In women, chest pain may be less predictive of coronary ischemia than in men.[3]

Approximately half of all MI patients have experienced warning symptoms such as chest pain prior to the infarction.[4]

Approximately one fourth of all myocardial infarctions are silent, without chest pain or other symptoms.[5] These cases can be discovered later on electrocardiograms or at autopsy without a prior history of related complaints. A silent course is more common in the elderly, in patients with diabetes mellitus[6]and after heart transplantation, probably because the donor heart is not connected to nerves of the host.[7] In diabetics, differences in pain threshold, autonomic neuropathy, and psychological factors have been cited as possible explanations for the lack of symptoms.

Early Recognition of MI Symptoms

Early recognition of symptoms of STEMI by the patient or someone with the patient is the first step that must occur before evaluation and life saving treatment can be obtained. Although many lay persons are generally aware that chest pain is a presenting symptom of acute myocardial infarction, they are unaware of the common associated symptoms, such as arm pain (or a slight radiation of pain), lower jaw pain, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis or anginal equivalents. [8]

In randomized trials, the average time for a patient with ST elevation myocardial infarction to seek medical care is 2.7 to 2.9 hours after symptom onset, and this pattern appears unchanged over the last decade.[8]

Likewise, average and median delays for patients with STEMI were 4.7 and 2.3 hours, respectively, from the 14-country Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) registry.

Data from the REACT research program demonstrated longer delay times among non Hispanic blacks, older patients, and Medicaid only recipients and shorter delay times among Medicare recipients (compared with privately insured patients) and among patients who came to the hospital by ambulance. [9] In the majority of studies examined to date, women in both univariate and multivariate adjusted analyses (in which age and other potentially confounding variables have been controlled) exhibit more prolonged delay patterns than men.[8]

Reasons for Delays in Symptom Recognition and Seeking Medical Care

It is notable that in the REACT study, while 89.4% of community survey respondents indicated that they would use EMS, only 23.2% of patients who in fact developed chest pain actually used EMS. Thus, there is a disconnect between what people know versus their actual course of behavior when confronted with a cardiac emergency. This may reflect potentially modifiable belief factors or situational factors.

One such modifiable factor is patient denial. It has been shown that if the patient believes the chest discomfort is due to a heart attack then they are more likely to call for EMS. On the other hand, if a patient can attribute the chest discomfort to another illness they are less likely to use Emergency Medical Services (EMS). One such scenario would include a patient who is self-prescribing antacids or aspirin. In contrast to these patients with other illnesses, those patients who were familiar with heart disease who were taking nitroglycerin were more likely to use EMS. These data point to the potential role of patient education in improving delays in seeking medical care.[10]

- Patient, lay person or relatives expected a dramatic presentation; patients or their relatives commonly hold a preexisting expectation that a heart attack would present dramatically with severe, crushing chest pain, such that there would be no doubt that one was occurring.

- Thought symptoms were not serious/would go away

- Took a wait and see approach to the initial symptoms that included self-evaluation, self-treatment, and reassessment until having a certain one

- Tended to attribute symptoms to other chronic conditions (e.g., arthritis, muscle strain) or common illnesses (e.g., influenza)

- Lacked awareness of the benefits of rapid action, reperfusion treatment, or of the importance of calling Emergency Medical Services or 911 for acute MI symptoms

- Expressed fear of embarrassment if symptoms turned out to be a false alarm; reluctant to bother physicians or EMS unless really sick; need permission from others such as health care providers, spouses, family to take rapid action.

- Few ever discussed symptoms, responses, or actions for a heart attack in advance with family or providers.

Transfer to Medical Facility

Patients with possible symptoms of STEMI should be transported to the hospital by ambulance rather than by friends or relatives, because there is a significant association between arrival at the emergency department by ambulance and early reperfusion therapy.

Other Life Threatening Diseases to Exclude Immediately in the Patient with Chest Pain

Acute MI is just one of several conditions that are life threatening. Other conditions that are potentially life threatening include the following:

References

- ↑ National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Heart Attack Warning Signs. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

- ↑ Acute Coronary Syndrome. American Heart Association. Retrieved November 25, 2006.

- ↑ McSweeney JC, Cody M, O'Sullivan P, Elberson K, Moser DK, Garvin BJ (2003). "Women's early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction". Circulation. 108 (21): 2619–23. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000097116.29625.7C. PMID 14597589. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ D Lee, D Kulick, J Marks. Heart Attack (Myocardial Infarction) by MedicineNet.com . Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ↑ Kannel WB (1986). "Silent myocardial ischemia and infarction: insights from the Framingham Study". Cardiol Clin. 4 (4): 583–91. PMID 3779719. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Davis TM, Fortun P, Mulder J, Davis WA, Bruce DG (2004). "Silent myocardial infarction and its prognosis in a community-based cohort of Type 2 diabetic patients: the Fremantle Diabetes Study". Diabetologia. 47 (3): 395–9. doi:10.1007/s00125-004-1344-4. PMID 14963648. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rubin's Pathology - Clinicopathological Foundations of Medicine. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001. pp. p. 549. ISBN 0-7817-4733-3. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Gibson CM (2001). "Time is myocardium and time is outcomes". Circulation. 104 (22): 2632–4. PMID 11723008. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Brown AL, Mann NC, Daya M; et al. (2000). "Demographic, belief, and situational factors influencing the decision to utilize emergency medical services among chest pain patients. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) study". Circulation. 102 (2): 173–8. PMID 10889127. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW; et al. (2004). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction)". Circulation. 110 (5): 588–636. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000134791.68010.FA. PMID 15289388. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)