Patent ductus arteriosus pathophysiology

|

Patent Ductus Arteriosus Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Patent Ductus Arteriosus from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Medical Therapy |

|

Case Studies |

|

Patent ductus arteriosus pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Patent ductus arteriosus pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Patent ductus arteriosus pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Priyamvada Singh, M.B.B.S. [2], Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3], Assistant Editor-In-Chief: Kristin Feeney, B.S. [4] Ramyar Ghandriz MD[5]

Overview

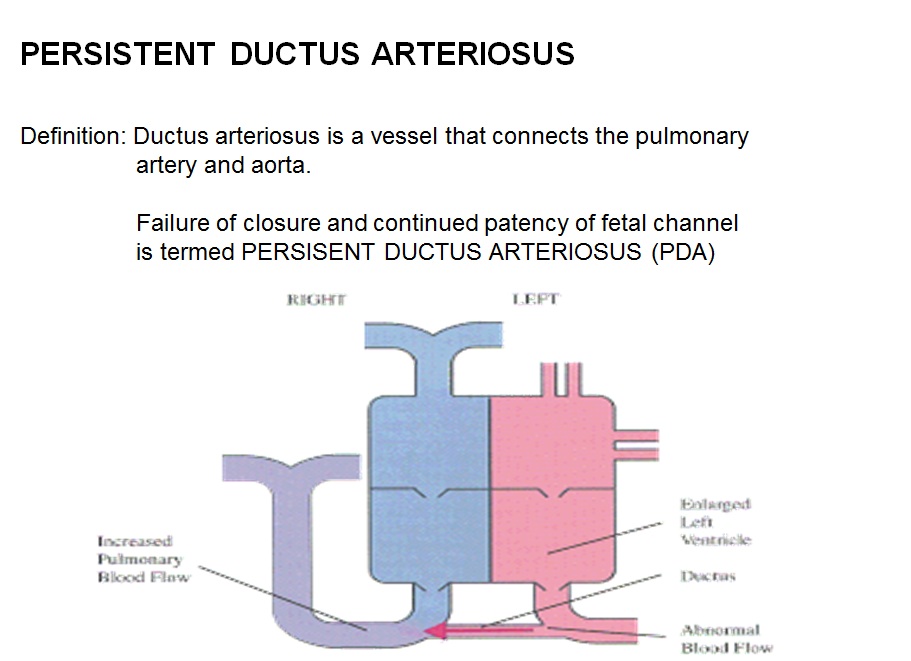

The pathophysiological consequences depend on the size of the defect and the pulmonary vascular resistance.Patent ductus arteriosus is a heart condition that is normal but reverses soon after birth. In a persistent PDA, there is an irregular transmission of blood between two of the most important arteries (aorta and pulmonary artery) in close proximity to the heart. Although the ductus arteriosus normally seals off within a few days, in PDA, the newborn's ductus arteriosus does not close, but remains patent.

Pathophysiology

Normal Ductus Arteriosus Closure

In the developing fetus, the ductus arteriosus (DA) is a shunt connecting the pulmonary artery to the aortic arch that allows much of the blood from the right ventricle to bypass the fetus' fluid-filled lungs.[1] During fetal development, this shunt protects the right ventricle from pumping against the high resistance in the lungs, which can lead to right ventricular failure if the DA closes in-utero.

When the newborn takes its first breath, the lungs open and pulmonary pressure decreases below that of the left heart.[2] At the same time, the lungs release bradykinin to constrict the smooth muscle wall of the DA and reduce blood flow. Additionally, because of reduced pulmonary resistance, more blood flows from the pulmonary arteries to the lungs and thus the lungs deliver more oxygenated blood to the left heart. This further increases aortic pressure so that blood no longer flows from the pulmonary artery to the aorta via the DA. In normal newborns, the DA is closed within 15 hours after birth and is completely sealed after three weeks. The fall in circulating maternal prostaglandins contributes to this. A nonfunctional vestige of the DA, called the ligamentum arteriosum, remains in the normal adult heart.[1]

Abormal Closure of Ductus Arteriosus

The abnormal closure of the ductus arteriosus results in patent ductus arteriosus. Patent ductus arteriosus is a heart condition that is normal but reverses soon after birth. In a persistent PDA, there is an irregular transmission of blood between two of the most important arteries in close proximity to the heart. Although the ductus arteriosus normally seals off within a few days, in PDA, the newborn's ductus arteriosus does not close, but remains patent.[3] PDA is common in infants with persistent respiratory problems such as hypoxia, and has a high occurrence in premature children. In hypoxic newborns, too little oxygen reaches the lungs to produce sufficient levels of bradykinin and subsequent closing of the DA. Premature children are more likely to be hypoxic and thus have PDA because of their underdeveloped heart and lungs.In some babies, on the other hand, the ductus arteriosus remains open. This opening permits blood to surge unswerving starting from the aorta into the pulmonary artery.

A patent ductus arteriosus allows oxygenated blood to flow down its pressure gradient from the aorta to the pulmonary arteries. Thus, some of the infant's oxygenated blood does not reach the body, and the infant becomes short of breath. The heart rate hastens, thereby increasing the speed with which blood is oxygenated and delivered to the body. Left untreated, the infant will likely suffer from congestive heart failure, as his heart is unable to meet the metabolic demands of his body.

In some cases, such as in transposition of the great vessels (the pulmonary artery and the aorta), a PDA may need to remain open. In this cardiovascular condition, the PDA is the only way that oxygenated blood can mix with deoxygenated blood. In these cases, prostaglandins are used to keep the patent ductus arteriosus open.

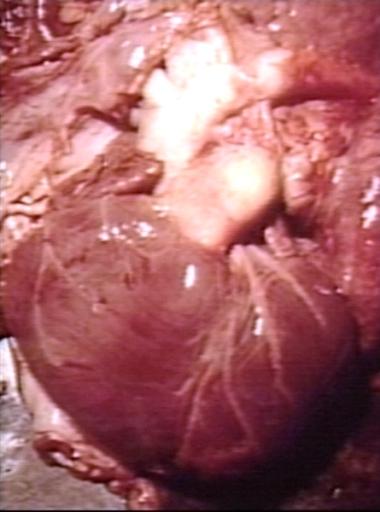

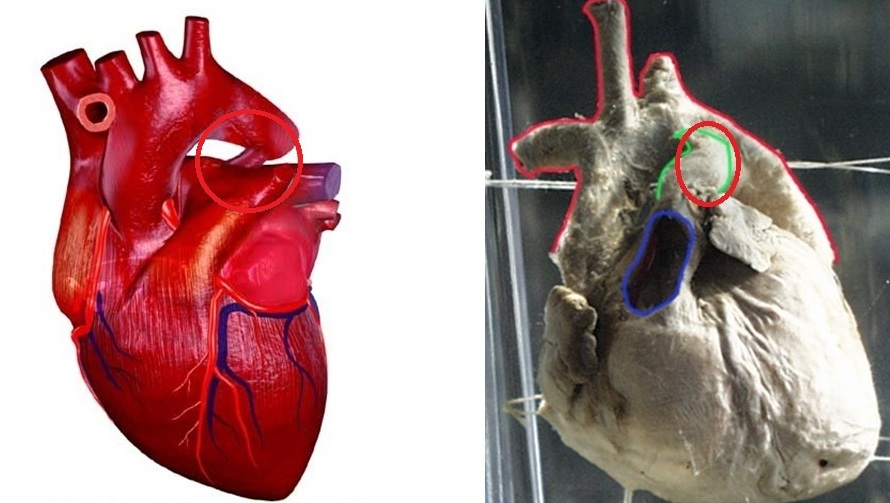

Shown below is the image below shows the gross anatomy of heart with patent ductus arteriosus.

Small-Sized PDA

- Small left-to-right shunt (Qp/Qs < 1.5)

- Normal ratio of pulmonary artery (PA) to systemic pressure.

- Shunt throughout the cardiac cycle, continuous murmur.

Medium-Sized PDA

- Qp/Qs 1.5 to 2.0 yet small enough to offer some resistance to flow.

- PA systolic to systemic pressures are < 0.5

- Unusual for this group to have markedly increased PVR.

- Due to increased return to the left heart, there is volume overload of the left atrium (LA) and the left ventricle (LV).

Large PDA

- Defect does not restrict flow.

- There is pulmonary hypertension at near systemic pressures (PA systolic/systolic pressure is >0.5).

- Because of the physiologic decrease in the PVR over the first three months of life there is a large left-to-right shunt with Qp/Qs > 2.

- The large volume overload of the left ventricle may result in LV failure.

- There is pulmonary hypertension.

- There may be two courses:

- A decrease in the relative size of the ductus compared with other cardiovascular structures. This results in a medium-sized defect compared with the course expected for a medium-sized defect.

- The development of severe pulmonary vascular obstructive disease, can occur at any time from age 3 until early adulthood. The left-to-right shunt converts to a right-to-left shunt with cyanosis and disappearance of the continuous murmur.

Gross Pathology

-

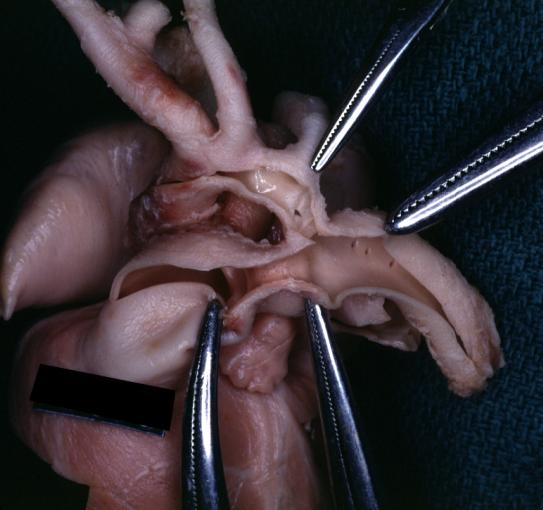

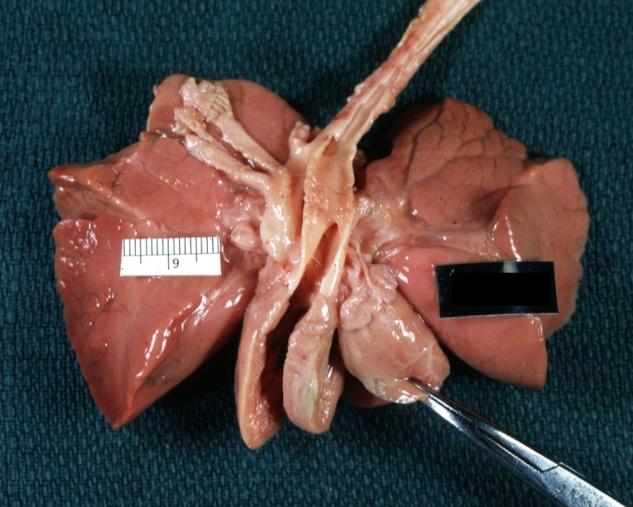

Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Gross example in an infant heart

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Gross fixed tissue probe in ductus

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Gross fixed tissue view of ductus opened from pulmonary artery into aorta with edematous appearing intimal surface

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Gross natural color opened ductus in infant shows apparent intimal edema in ductus.

-

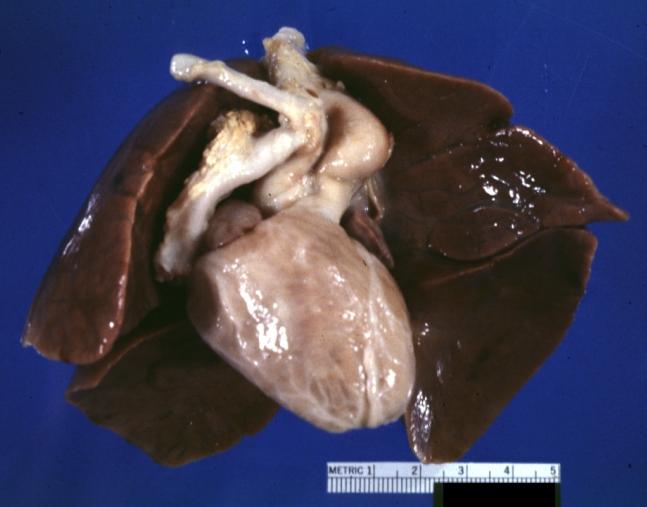

Patent Ductus Arteriosus with Aneurysmal Dilation: Gross fixed tissue external photo of heart shows the lesion

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus with Aneurysmal Dilation: Gross fixed tissue aorta and ductus have been cross sectioned showing arch of aorta and huge ductus in a 5 day old infant

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus with Aneurysmal Dilation: Gross fixed tissue opened aortic arch and descending thoracic showing very large opening of ductus into aorta

-

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Shown below is the pictoral image of pathophysiology of patent ductus arteriosus

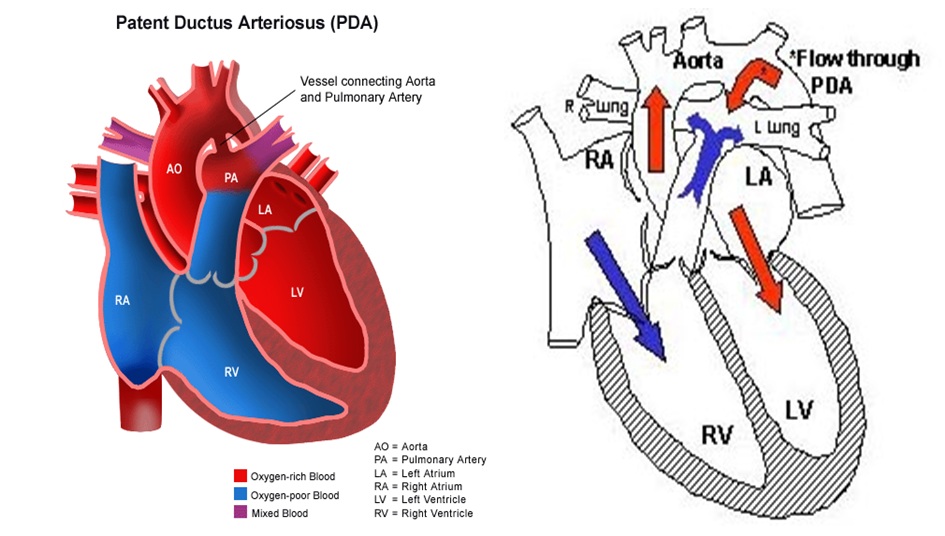

Shown below is the image of pathophysiology of patent ductus arteriosus in the cross-section of the heart

Videos

{{#ev:youtube|watch?v=7DKaCqubuSg}}

Diagram

Diagram of heart showing a patent ductus arteriosus

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hermes-DeSantis, E R; Clyman, R I (2006). "Patent ductus arteriosus: pathophysiology and management". Journal of Perinatology. 26 (S1): S14–S18. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211465. ISSN 0743-8346.

- ↑ Clyman, Ronald I. (2006). "Mechanisms Regulating the Ductus Arteriosus". Neonatology. 89 (4): 330–335. doi:10.1159/000092870. ISSN 1661-7800.

- ↑ Giuliani et al, Cardiology: Fundamentals and Practice, Second Edition, Mosby Year Book, Boston, 1991, pp. 1653-1663.