Premature ventricular contraction

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Premature ventricular contraction (PVC), also known as ventricular premature beat (VPB) or extrasystole, is a form of irregular heartbeat in which the ventricle contracts prematurely. This results in a "skipped beat" followed by a stronger beat. Individuals with the condition may report feeling that his or her heart "stops" after a symptom. PVCs are also called heart palpitations (although there are many other forms of arrhythmia). The depolarization begins in the ventricle instead of the usual place, the sinus node. PVCs can be a useful natural probe, since they induce Heart rate turbulence whose characteristics can be measured, and used to evaluate cardiac function.

Epidemiology and Demographics

PVCs are a very common form of arrhythmia, and can occur in both individuals with and without heart disease. They can also occur in otherwise healthy athletes (e.g. in the days following a major effort such as a marathon. Estimates of the prevalence of PVCs vary greatly.

In children, PVCs occur less frequently than in adults, although healthy children are known to have episodes of PVC. In fact, on routine monitoring of children aged 10-13 years with a Holter monitor, about 20% of healthy boys had occurrences of PVC. In otherwise healthy newborns, PVCs will often resolve on their own by the 12th week of life, and almost never require treatment.

Differential Diagnosis of Causes of PVCs

Some possible causes of PVC in adults include the use of cocaine, amphetamines, alcohol, and tobacco. Medicines including digoxin, sympathomimetics, tricyclic antidepressants, and aminophylline have also been known to trigger attacks of PVC. Increased levels of adrenaline are thought to play a role, often caused by caffeine, exercise or anxiety. [1]

Heart conditions or a previous history of heart attack, ischemia, myocarditis, dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myocardial contusion, atrial fibrillation and mitral valve prolapse may cause PVC. Patients with hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia may also present with PVC.

PVCs in young children are thought to be associated with developmental factors of the autonomic nervous system. In older children, sympathomimetic drugs, such as cold or asthma medication may cause PVCs, along with mild cases of viral myocarditis.

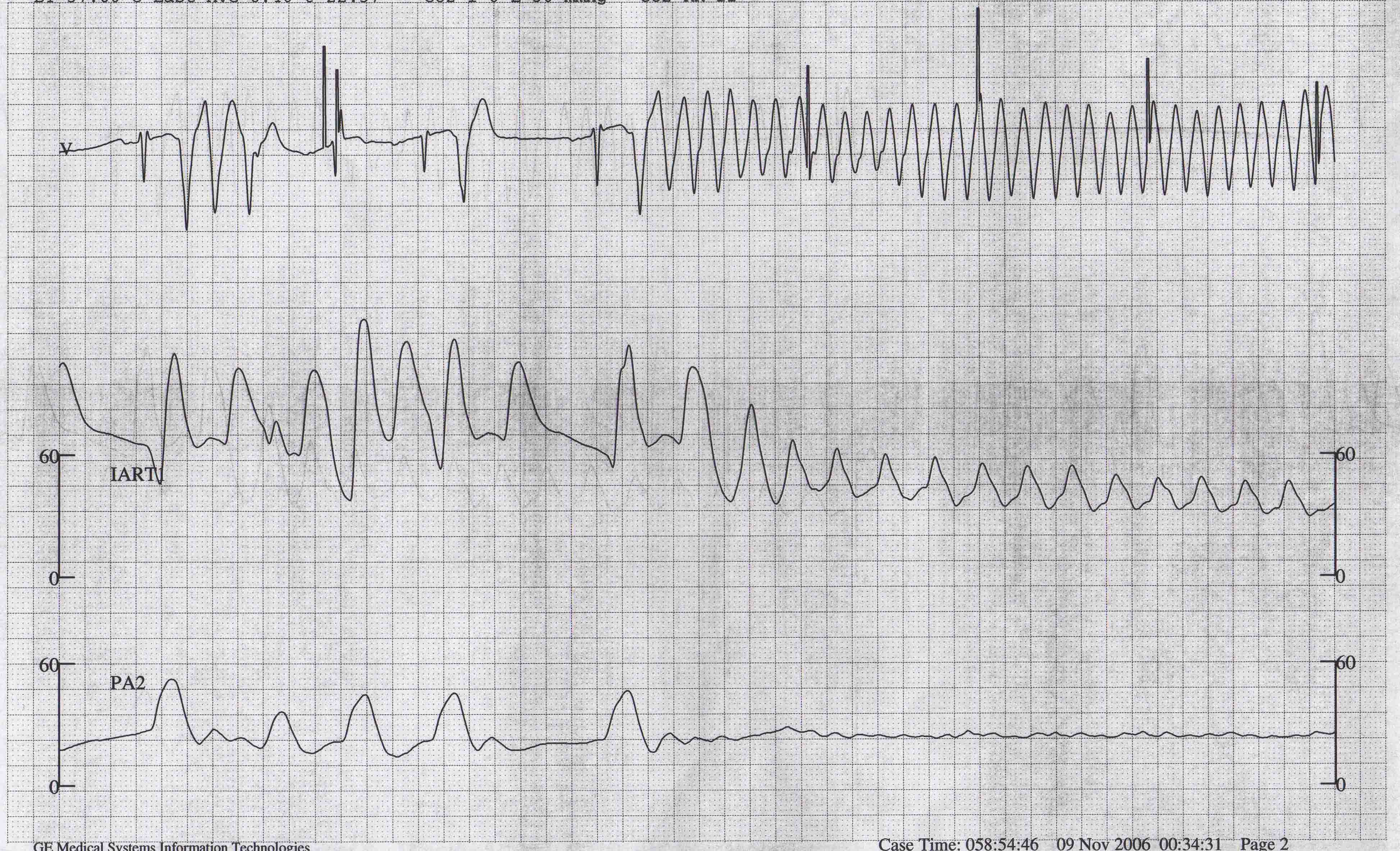

Diagnosis

PVCs are diagnosed by an ECG or a TMT but some patients will need to wear a Holter monitor to record PVCs that occur outside the doctor's office or hospital. PVCs are often benign but may be a sign of a heart condition. PVCs may be unifocal (coming from the same part of the heart and having the same shape on the ECG) or multifocal (coming from several parts of the heart and having various shapes on the ECG). On the ECG, PVCs are diagnosed by: 1. prematurity 2. wide QRS 3. the presence (usually) of a compensatory pause.

In healthy individuals, PVCs can often be resolved with continuous rehydration and by repleting the balance of magnesium, calcium and potassium within the body.

Possible triggers

- Anxiety/Stress

- Chocolate

- Caffeine

- Calcium/magnesium imbalance

- Dehydration

- Alcohol

- Exercise

- Hormonal imbalance

- Hypercapnia (CO2 poisoning)

- Hyperstimulation of the Vagus nerve

- Lack of sleep/exhaustion

- Overeating

- Low copper

- MSG

EKG Findings

- The beats are premature in relation to the expected beat of the basic rhythm

- Ectopic beats from the same focus tend to have a constant coupling interval (the interval between the ectopic beat and the preceding beat of the basic sinus rhythm).

- They do not vary from each other by more than 0.08 seconds if the focus is the same.

- PVCs with the same morphology but with a varying coupling interval should make one suspect a parasystolic mechanism.

- A longer RR interval is followed by a relatively longer coupling interval

- The QRS complex is abnormal in duration and configuration. There are secondary ST segment and T wave changes. The morphology of the QRS may vary in the same patient.

- There is usually a full compensatory pause following the PVC.

- The sum of the RR intervals that precede and follow the ectopic beat (or the RR interval that contains the PVC) equals two RR intervals of the sinus beats.

- Because of sinus arrhythmia, the RR interval that contains the PVC may not be exactly twice the duration of the RR interval of the adjacent sinus beat, even though a full compensatory pause does exist).

- Retrograde capture may or may not occur.

- They may occur in various frequency and distribution patterns such as bigeminy, trigeminy (occurrence of a PVC every third beat), quadrigeminy (occurrence of a PVC every fourth beat), and couplets (Two ventricular premature complexes in a row). These are called complex PVCs.

- Occasionally PVCs may be interpolated.

Grading of Frequency

- Called frequent if there are 5 or more PVCs per minute on the routine ECG

- Lown and Graboys proposed the following grading system which is used for prognostic purposes:

- Grade 0 = No PVCs

- Grade 1 = Occasional (<30 per hour)

- Grade 2 = Frequent (>30 per hour)

- Grade 3 = Multiform

- Grade 4 = Repetitive

- A = Couplets

- B = Salvos of > 3

- Grade 5 = R-on-T

Tips and Clues for Differential Diagnosis

A full listing of the causes of Premature Ventricular Contractions can be found here

Aberrant ventricular conduction is:

- A transient form of abnormal IVCD

- Occurs when there is unequal refractoriness of the two bundles

- The right bundle has a longer action potential duration, and is more vulnerable to conduction delay or failure.

- The refractory period is affected by the preceding cycle length.

- The refractory period is longer when there is a long preceding RR interval

- aberrant ventricular conduction is favored when a premature supraventricular impulse comes after a long preceding RR interval (Ashman phenomenon).

- If the underlying rhythm is sinus in origin, and if the abnormal QRS is preceded by a premature P wave, then the ectopic beat is likely to be supraventricular in origin.

- The absence of a fully compensatory pause further supports this diagnosis.

- If a retrograde P wave is identifiable after the QRS complex and the RP interval is less than 0.11 second, the premature beat is likely to have originated from the AV junction, since the RP interval is too short for VA conduction (unless an accessory pathway is present).

- A long RP interval of 0.20 seconds or longer is suggestive but not diagnostic of a PVC, since the retrograde conduction time of a junctional beat is less likely to exceed this duration.

- The beat is more likely to be due to aberrancy if the initial forces are similar to those of the sinus beat and if it has an RSR' configuration in lead V1.

- If the QRS complexes in all the precordial leads are positive or all negative,then a PVC is more likely.

- Diagnosis of PVCs in the presence of atrial fibrillation:

- Absence of P waves and the irregularity of the rhythm are the handicaps.

- A constant coupling time is suggestive of PVCs.

- Ashman phenomenon. Keep in mind that a long cycle length also favors the precipitation of a PVC, therefore this sign is helpful but not diagnostic of aberrancy.

- PVC is favored if the abnormal complex terminates a short-long cycle.

Differential Diagnosis: Causes of Premature Ventricular Contractions

- Acidosis

- Addison's Disease

- After heart catheterization

- After heart surgery, trauma

- Amyloidosis

- Brucellosis

- Cardiac Valve Disease

- Cirrhosis

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Cor Pulmonale

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Diaphragmatic eventration

- Diptheria

- Drugs, toxins

- Electrocution

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Emotional stress

- Glycogen storage disease

- Heart failure

- Hemochromatosis

- Hypercalcemia

- Hyperkalemia

- Hypertension

- Hyperthyroidism

- In healthy persons

- Intoxication

- Long QT syndrome

- Meteorism

- Perimyocarditis

- Pheochromocytoma

- Protein deficiency

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Rheumatic Fever

- Scarlet Fever

- Scleroderma

- STEMI

- Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Clinical Correlation

- Healthy patients

- The most common arrhythmia in patients with and without CAD.

- Less common in infants and children, more common in the elderly.

- Usually originate from the RV.

- In normal patients, they may be either precipitated or suppressed by exercise.

- No relationship to coffee or smoking has been established.

- Frequency decreases with sleep.

- Coronary artery disease

- Routine ECGs demonstrate PVCs in 10% of patients with CAD.

- Incidence inreases to 60 to 88% when the monitoring is increased to 12 to 24 hours.

- The frequency of complex VEA increases with increasing numbers of vessels involved. (40% with one, 53% with two, and 78% with three vessels involved has VEA).

- Patients with CAD are more prone to develop VEA with exercise (incidence 4 times higher than age matched controls).

- Reported incidence in acute MI varies, but is near 100%.

- After the initial 6 hours, the frequency decreases.

- Persistence of VEA is associated with larger infarct size.

- In one study, patients with EFs of greater than 50% had no persistent VEA, and patients with EFs of less than 30% had frequent PVCs.

- Other Organic Heart Diseases:

- occur on routine EKG in 1/3rd of patients.

- 12% of patients with congested cardiomyopathy have PVC on routine tracings.

- 1.6% of patients with IHSS have PVCs on routine EKG.

- Drugs:

- PVCs are the most common arrhythmia in patients with digoxin toxicity.

- Other drugs that cause PVCs are quinidine, PCA, norpace, phenothiazines and tricyclic antidepressants.

- Electrolyte Imbalance:

- Hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypercalcemia are frequently associated with the appearance of ventricular arrhythmias.[4] [5]

Prognostic Significance

- In the absence of CAD or HTN, there is no excess mortality in patients with PVCs.

- On the other hand, PVCs in the presence of other cardiac abnormalities or hypertension is associated with a mortality twice that expected.

- The development of VT is most likely in those with greater than 12 PVCs/min, couplets, and multifocal PVCs.

- Complex VEA during acute MI does not have any prognostic significance.

- Their presence 2 to 3 weeks after acute MI is associated with a 3 fold increase in the risk of sudden death.

Treatment

If asymptomatic, no treatment may be necessary

- Medicinal/supplements

- Magnesium supplements (e.g. magnesium citrate, orate, etc.)

- Calcium supplements (e.g. citrate, etc.)

- Hawthorn extract

- CoQ10

- Fish oil

- Potassium citrate

- Beta blockers (Propranolol, Atenolol, Toprol XL)

- Maalox

- Xanax

- Kava

- Lifestyle/other

- Frequent aerobic exercise

- Avoiding the triggers

- Exercise

- Aerobic exercises

- Deep breathing

- Hands in ice water

- Coughing (while holding breath)

- Losing weight

- Good support group

- Burping

See also

References

- ↑ Premature ventricular contractions. MayoClinic.com

- ↑ Chou's Electrocardiography in Clinical Practice Third Edition, pp. 398-409.

- ↑ Sailer, Christian, Wasner, Susanne. Differential Diagnosis Pocket. Hermosa Beach, CA: Borm Bruckmeir Publishing LLC, 2002:194 ISBN 1591032016

- ↑ Chou's Electrocardiography in Clinical Practice Third Edition, pp. 398-409.

- ↑ Sailer, Christian, Wasner, Susanne. Differential Diagnosis Pocket. Hermosa Beach, CA: Borm Bruckmeir Publishing LLC, 2002:194 ISBN 1591032016

External Links

- People with PVCs

- ECGpedia: Course for interpretation of ECG

- The whole ECG - A basic ECG primer

- 12-lead ECG library

- Simulation tool to demonstrate and study the relation between the electric activity of the heart and the ECG

- ECG information from Children's Hospital Heart Center, Seattle

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Diseases and Conditions Index

- A history of electrocardiography

- EKG Interpretations in infants and children