Ebola epidemiology and demographics

|

Ebola Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Postmortem Care |

|

Case Studies |

|

Ebola epidemiology and demographics On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Ebola epidemiology and demographics |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Ebola epidemiology and demographics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Michael Maddaleni, B.S.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Outbreaks

Outbreaks of EVD have mainly been restricted to Africa. The virus often consumes the population. Governments and individuals quickly respond to quarantine the area while the lack of roads and transportation helps to contain the outbreak. The potential for widespread EVD epidemics is considered low due to the high case-fatality rate, the rapidity of demise of patients, and the often remote areas where infections occur.

Ebola outbreaks have been restricted to Africa, with the exception of Reston ebolavirus. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses currently recognizes four species of the Ebola: Zaire virus (ZEBOV), Sudan ebolavirus (SEBOV), Reston ebolavirus (REBOV), and Cote d'Ivoire ebolavirus (CIEBOV).

Recent outbreaks

West Africa outbreak

On March 23, 2014, the Ministry of Health of Guinea notified the World Health Organization WHO) of a rapidly evolving outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in forested areas south eastern Guinea: Guekedou, Macenta, Nzerekore and Kissidougou districts. As of 22 March, 2014, a total of 49 cases including 29 deaths (case fatality ratio: 59%) were reported. Four health care workers were among the victims. At the same time, suspected cases in border areas of Liberia and Sierra Leone were being investigated. Six blood samples were tested at Institut Pasteur in Lyon, France, resulting positive for Ebola virus by PCR, confirming the first Ebola virus disease outbreak in Guinea. Preliminary results from sequencing of a part of the L gene showed strong homology with Zaire Ebolavirus. The ministry of health together with the WHO and other partners initiated measures to control the outbreak and prevent further spread. Médecins Sans Frontières, Switzerland (MSF-CH) started working in the affected areas and assisted with the establishment of isolation facilities, and also supported transport of the biological smaples from suspected cases and contacts to international reference laboratories for urgent testing. The Emerging and Dangerous Pathogens Laboratory Network (EDPLN) worked with the Guinean VHF Laboratory in Donka, the Institut Pasteur in Lyon, the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, and the Kenema Lassa fever laboratory in Sierra Leone to make available appropriate Filovirus diagnostic capacity in Guinea and Sierra Leone.[1]

On 30 March, 2014, the Ministry of Health of Liberia provided updated details on the suspected and confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease in Liberia. As of 29 March, seven clinical samples, all from adult patients from Foya district, Lofa County, were tested by PCR using Ebola Zaire virus primers by the mobile laboratory of the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar in Conakry. Two of those samples tested positive for the ebolavirus. There were 2 deaths among the suspected cases; a 35 year-old woman who died on 21 March tested positive for ebolavirus while a male patient who died on 27 March tested negative. At that time, Foya was the only district in Liberia that reported confirmed or suspected cases of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. As of 26 March, Liberia had 27 contacts under medical follow-up. Liberia established a high level National Task Force to lead the response. Response partners include WHO, the International Red Cross (IRC), Samaritan’s Purse (SP) Liberia, Pentecostal Mission Unlimited (PMU)-Liberia, CHF-WASH Liberia, PLAN-Liberia, UNFPA and UNICEF.[3]

On 3 April, 2014, the outbreak was confirmed to be caused by a strain of ebolavirus with very close homology (98%) to the Zaire ebolavirus. This is the first time the disease has been detected in West Africa.[4]

As of 17 June 2014, in Guinea a total of 7 new cases and 5 new deaths were reported from Gueckedou (4 cases and 5 deaths) and Boffa (3 cases and 0 deaths). This brings the cumulative number of cases and deaths reported from Guinea to 398 (254 confirmed, 88 probable and 56 suspected) and 264 deaths. The geographical distribution of these cases and deaths is as follows: Conakry (70 cases and 33 deaths); Guéckédou (224 cases and 173 deaths); Macenta (41 cases and 28 deaths); Dabola, (4 cases and 4 deaths); Kissidougou (8 cases and 5 deaths); Dinguiraye (1 case and 1 death); Telimele (30 cases and 9 deaths); Bofa (19 cases and 10 deaths) and Kouroussa (1 case and 1 death). Twenty four (24) patients are currently in EVD Treatment Centres: Conakry (6), Guéckédou (9), Telimele (3) and Boffa (6). The number of contacts currently being followed countrywide is 1,258 and distributed as follows: Conakry (252), Guéckédou (529), Macenta (52), Telimele (118), Dubreka (118) and Boffa (189). So far 69.4% (2,848 contacts being followed-up out of a 4,106 contacts registered since the beginning of the outbreak) have completed the mandatory 21 days observation period.

In Liberia a total of 9 new cases and 5 new deaths were reported from Lofa (6 cases and 0 death) and Montserado (3 cases and 5 deaths). This brings the cumulative number of cases and deaths reported from Liberia to 33 (18 confirmed, 8 probable and 7 suspected) and 24 deaths. The geographical distribution of these cases and deaths is as follows: Lofa (21 cases and 14 deaths); Montserado (8 cases and 8 deaths); Margibi (2 cases and 2 deaths) and Nimba (2 cases and 0 death). Five (5) patients are currently in EVD Treatment Centres in Lofa. The number of contacts currently being followed countrywide is 108 and distributed as follows: Lofa (95), Montserado (13). So far 41.5% (108 contacts being followed-up out of a 260 contacts registered since the beginning of the outbreak) have completed the mandatory 21 days observation period.

In Sierra Leone a total of 31 new cases and 4 new deaths were reported from Kailahun (29 cases and 4 deaths), Kono (1 case) and Western (1 case). This brings the cumulative number of cases and deaths reported from Sierra Leone to 97 (92 confirmed, 3 probable and 2 suspected) and 49 deaths. The geographical distribution of these cases and deaths is as follows: Kailahun (92 cases and 46 deaths); Kambia (1 cases and 0 deaths); Port Loko (2 cases and 1 deaths); Kono, (1 case and 0 death) and Western (1 cases and 1 death. Thirty three (33) patients are currently in EVD Treatment Centre of Kenema. The number of contacts currently being followed countrywide is 37 from Kailahun. Contact listing is continuing in Kailahun, Kambia and Port Loko.[5]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

As of August 30, 2007, 103 people (100 adults and three children) were infected by a suspected hemorrhagic fever outbreak in the village of Mweka, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The outbreak started after the funerals of two village chiefs, and 217 people in four villages fell ill. The World Health Organization sent a team to take blood samples for analysis and confirmed that many of the cases are the result of the Ebola virus [6]. The Congo's last major Ebola epidemic killed 245 people in 1995 inKikwit, about 200 miles from the source of the Aug. 2007 outbreak.[7]

On November 30, 2007, the Uganda Ministry of Health confirmed an outbreak of Ebola in the Bundibugyo District. After confirmation of samples tested by the United States National Reference Laboratories and the Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization confirmed the presence of a new species of the Ebola virus.[8] The epidemic came to an official end on February 20, 2008. 149 cases of this new strain were reported and 37 of those led to deaths.

Uganda Outbreak

On October 8, 2000, an outbreak of an unusual febrile illness with occasional hemorrhage and significant mortality was reported to the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Kampala by the superintendent of St. Mary's Hospital in Lacor, and the District Director of Health Services in the Gulu District. A preliminary assessment conducted by MoH found additional cases in Gulu District and in Gulu Hospital, the regional referral hospital. On October 15, suspicion of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) was confirmed when the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Johannesburg, South Africa, identified Ebola virus infection among specimens from patients, including health-care workers at St. Mary's Hospital. This report describes surveillance and control activities related to the EHF outbreak and presents preliminary clinical and epidemiologic findings.

Control activities were organized around surveillance and epidemiology, clinical case management, social education and mobilization, and coordination and logistic support. An active EHF surveillance system was initiated to determine the extent and magnitude of the outbreak, identify foci of disease activity, and detect cases early. Ill persons were encouraged to be assessed at a hospital and, if indicated, to be hospitalized to reduce further community transmission. Targeted prevention activities included follow-up of contacts of identified cases for 21 days; establishment of trained burial teams for all potential and confirmed EHF deaths; community education; cessation of traditional healing and burial practices; cessation of large public gatherings; and updates of hospital infection-control measures, including isolation wards. Laboratory testing was performed at a field laboratory established at St. Mary's Hospital by CDC and supplemented by additional testing at CDC and NIV. Sequence analysis revealed that the virus associated with this outbreak was Ebola-Sudan and differed at the nucleotide sequence level from earlier Ebola-Sudan isolates by 3.3% and 4.2% in the polymerase (362 nucleotides sequenced) and nucleocapsid (146 nucleotides sequenced) protein encoding genes, respectively.

During the third week of October, active surveillance was established and included three case notification categories: alert, suspect, and probable. The alert category comprised persons with sudden onset of high fever, sudden death, or hemorrhage, and was used by community members to alert health-care personnel. The suspect category comprised persons with fever and contact with a potential case-patient; persons with unexplained bleeding; persons with fever and three or more specified symptoms (i.e., headache, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, weakness or severe fatigue, abdominal pain, body aches or joint pains, difficulty swallowing, difficulty breathing, and hiccups), and all unexplained deaths. The suspect category was used by mobile surveillance teams to determine whether a patient required transport to an isolation ward. The probable category included persons who met these criteria and were assessed and reported by a physician. Laboratory tests included virus antigen detection and antibody ELISA tests and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Laboratory-confirmed case-patients were defined as patients who met the surveillance case definitions and were either positive for Ebola virus antigen or Ebola IgG antibody.

During October 5--November 27, among 62 persons with laboratory-confirmed EHF admitted to Gulu Hospital, symptoms included diarrhea (66%), asthenia(64%),anorexia (61%), headache (63%), nausea and vomiting (60%), abdominal pain (55%), and chest pain (48%). Patients presented for care a mean of 8 days (range: 2--20 days) after symptom onset. Bleeding occurred in 12 (20%) patients and primarily involved the gastrointestinal tract. Among the 62 confirmed case-patients, 36 (58%) died; among patients aged <15 years, four of five died (case fatality: 80%). Spontaneous abortions were reported among pregnant women infected with EHF. Patients who died usually exhibited a rapid progression of shock, increasing coagulopathy, and loss ofconsciousness.

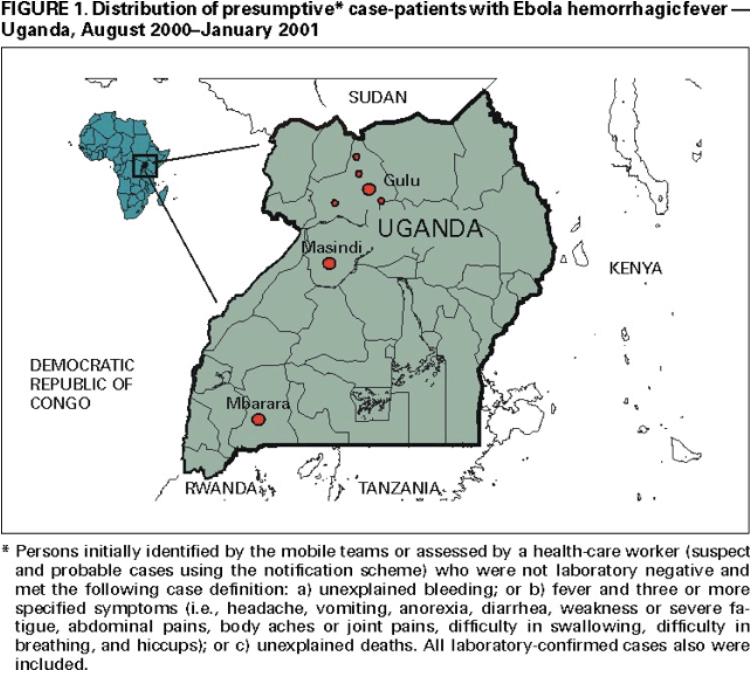

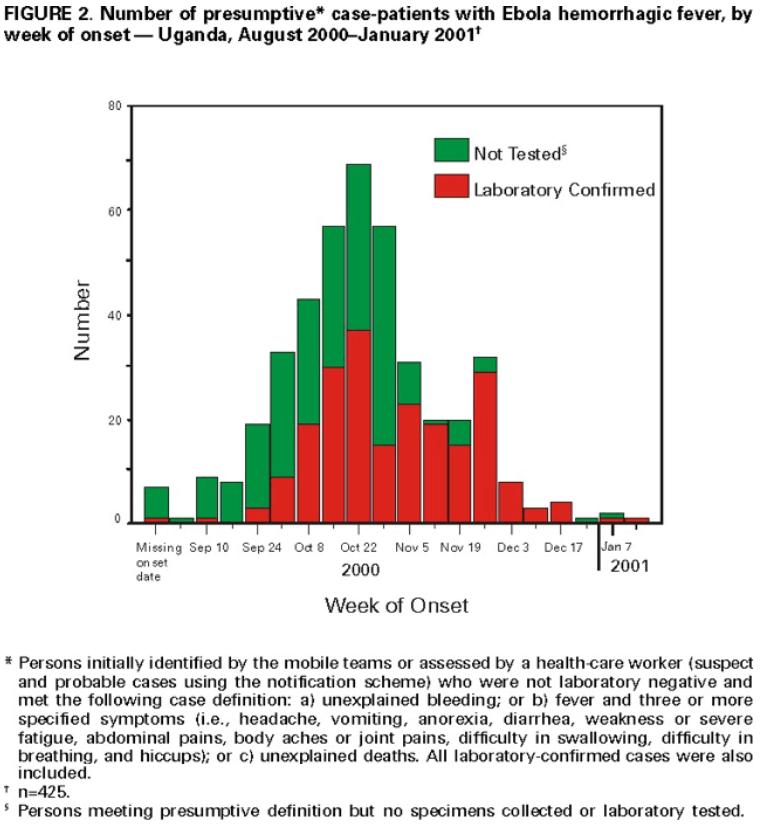

As of January 23, 2001, 425 presumptive* case-patients with 224 (53%) deaths attributed to EHF were recorded from three districts in Uganda: 393 (93%) from Gulu, 27 (6%) from Masindi, and five (1%) from Mbarara. The combined area comprises approximately 11,700 square miles (31,000 square kilometers; 2000 combined population: 1.8 million) (See the map of Uganda below) (1). Although the cluster of cases in early October triggered identification of the outbreak and response measures, investigations (i.e., case-record review and interviews with surviving patients or their surrogates) identified cases occurring in the community and patients hospitalized several weeks earlier. The onset of illness of the earliest presumptive case was August 30, 2000, and onset of last presumptive case was January 9, 2001 (See the graph below the map of Uganda). The ages of presumptive case-patients ranged from 3 days--72 years (median: 28 years); 269 (63%) were women. Mean time from symptom onset to death was 8 days (95% confidence interval=±5 days); 218 (51%) presumptive cases were laboratory confirmed.

Epidemiologic investigations identified the three most important means of transmission as attending funerals of presumptive EHF case-patients where ritual contact with the deceased occurred, and intrafamilial or nosocomial transmission. Fourteen (64%) of 22 health-care workers in Gulu were infected after establishing the isolation wards; these incidences led to the reinforcement of infection-control measures. Two distant focal outbreaks were initiated by movement of infected contacts of EHF cases from Gulu to Mbarara and Masindi districts. National notification and surveillance efforts led to the rapid identification of these foci and effective containment.

Distribution

This is a map of the distribution of ebola in Africa.

- Distribution of Ebola and Marburg virus in Africa (note that integrated genes from filoviruses have been detected in mammals from the New World as well). (A) Known points of filovirus disease. Projected distribution of ecological niche of: (B) all filoviruses, (C) ebolaviruses, (D) marburgviruses.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever in Guinea".

- ↑ "Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in West Africa (situation as of 16 June 2014)".

- ↑ "30 March 2014 Ebola virus disease in Liberia".

- ↑ "3 April 2014 Ebola virus disease: background and summary".

- ↑ "Ebola virus disease, West Africa (Situation as of 17 June 2014)".

- ↑ "Ebola Outbreak Confirmed in Congo". NewScientist.com. 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ "Mystery DR Congo fever kills 100". BBC News. 2007-08-31. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ "Uganda: Deadly Ebola Outbreak Confirmed -UN". UN News Service. 2007-11-30. Retrieved 2008-02-25.