Chronic stable angina diagnosis

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Chronic stable angina diagnosis further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Associate Editor-in-Chief: Smita Kohli, M.D.

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Click here for the Chronic stable angina main page

Overview

Once the history and physical exam is complete and a pretest probability has been determined, the clinician should proceed with dignostic tests. Laboratory tests, ECG and chest X-ray are normal in majority of the cases. Other tests are stress ECG testing, Echocardiography, myocardial perfusion imaging and coronary angiography. These are discussed below.

Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory Tests

- Total Cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) measurements should be performed in all patients with suspected or documented ischemic heart disease.

- Fasting glucose level

- Routine hematologic tests are necessary to exclude significant anemia

- Thyroid function tests are necessary to exclude abnormal thyroid functions, which can be associated with worsening angina.

- Homocysteinemia has been found to be a risk factor for CAD. Folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 can lower the homocysteine level. Although the therapeutic implications of lowering homocysteine levels have not been fully defined, homocysteine concentrations should be measured in patients with a strong family history of coronary disease, especially if it is not explained by traditional risk factors.

- Fibrinogen: Elevated fibrinogen levels are associated with higher risks of coronary artery disease, but in practice, coagulation studies are not recommended.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Recommendations for Initial Laboratory Tests for Diagnosis (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Hemoglobin. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Fasting glucose. (Level of Evidence: C) 3. Fasting lipid panel, including total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and calculated LDL cholesterol. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

Chest x-ray

Routine chest x-ray examination is important evaluation in patients with signs or symptoms of congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, pericardial disease, or aortic dissection/aneurysm.

Electrocardiography (ECG)

The ECG is critical not only to add support to the clinical suspicion of CAD but also to provide prognostic information based on the pattern and magnitude of the abnormalities.

ECG at rest

It is in normal range in approximately half of patients with chronic stable angina without a history of previous myocardial infarction. In the others, a variety of ECG finding may suggest an ischemic heart disease. Q waves may suggest prior myocardial infarction, but in the absence of a clinical history of previous myocardial infarction or CAD, Q waves may also be caused by other conditions, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy, dilated non ischemic cardiomyopathy and accessory conduction pathways. Isolated Q waves in lead III or QS pattern in V1 and V2 are nonspecific for diagnosis.

The occurrence of ST segment depression and T wave inversion in the resting ECG]], and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, left bundle branch block (LBBB) and left anterior hemiblock LAH are compatible with, favors to, but are not specific for CAD. A physician should consider these abnormal ECG findings as indications for further evaluation. Giant T-wave inversion in precordial leads is sometimes an important indicator of severe Left Anterior Descending (LAD) artery stenosis.

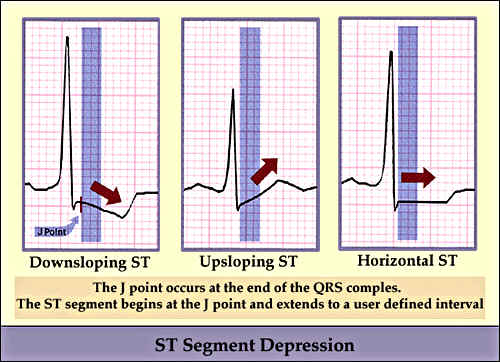

ST segment changes in angina can be seen as downsloping, upsloping or horizontal ST depressions.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- ECG / Chest X-Ray (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Rest ECG in patients without an obvious noncardiac cause of chest pain. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Rest ECG during an episode of chest pain. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Chest x-ray in patients with signs or symptoms of congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, pericardial disease, or aortic dissection/aneurysm. (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIa1. Chest x-ray in patients with signs or symptoms of pulmonary disease. (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIb1. Chest x-ray in other patients. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Electron beam computed tomography. (Level of Evidence:B) |

” |

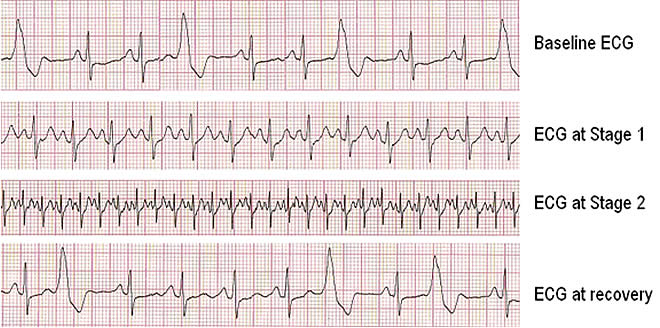

Exercise ECG

The exercise ECG is more useful than the resting ECG in detecting myocardial ischemia and evaluating the cause of chest pain. Down sloping or horizontal ST segment depressions are very suggestive of myocardial ischemia, particularly when these changes occur at a low workload, during early stages of exercise, persist for more than 3 minutes after exercise, or are accompanied by chest discomfort that is compatible with angina. Upsloping ST segments are much less specific indicators of CAD.

An abnormal resting ECG associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, intra ventricular conduction abnormalities, preexcitation syndromes (Long Ganong Lewine=LGL, Wolf Parkinson White=WPW and Mahaim type), electrolyte imbalance or therapy with digitalis increases the probability that an exercise ECG will yield a false positive result. In women, the lower prior probability of CAD is associated with more false positive results on ECG.

On the other hand, a fall in systolic pressure of 10 mmHg or more during exercise or the appearance of a murmur of mitral regurgitation during exercise increases the probability that, an abnormal stress ECG is a true positive test result.

Treadmill exercise test is more preferable to bicycle exercise test (or ergometer) for detecting myocardial ischemia. In patients who cannot perform treadmill exercise, pharmacologic stress scintigraphy or echocardiography is preferable to upper body arm exercise.

Exercise electrocardiography has a sensitivity of about 70% for detecting CAD and a specificity of about 75% for excluding it. To assess the probability of coronary artery disease in an individual patient, the exercise ECG result must be integrated with the clinical presentation.

- Variables of the Treadmill Exercise Test which indicate the high risk

- Short exercise duration <5 METs,

- Significant ST segment depression (magnitude ≥2 mm, starts at exercise stage I or II, duration of exercise test is <5 minutes and ≥5 leads with ST changes,

- Significant changes in blood pressure: low peak systolic blood pressure (<130 mm Hg), significant decrease in systolic blood pressure during the test (below the resting standing blood pressure),

- Inability to attain to the target heart rate,

- Presence of exercise induced angina,

- Presence of frequent ventricular ectopy (e.g. couplets or tachycardia) at low workload.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Exercise ECG for Diagnosis (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Patients with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD based on age, gender, and symptoms, including those with complete right bundle-branch block or <1 mm of rest ST depression (exceptions are listed below in classes II and III). (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIa1. Patients with suspected vasospastic angina. (Level of Evidence: C) Class IIb1. Patients with a high pretest probability of CAD by age, gender, and symptoms. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Patients with a low pretest probability of CAD by age, gender, and symptoms. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Patients taking digoxin with ECG baseline ST segment depression <1 mm. (Level of Evidence: B) 4. Patients with ECG criteria for LV hypertrophy and <1 mm of baseline ST-segment depression. (Level of Evidence: B) Class III1. Patients with the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

2. Patients with an established diagnosis of CAD due to prior MI or coronary angiography; however, testing can assess functional capacity and prognosis. (Level of Evidence: B) |

” |

Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy (Myocardial Perfusion Imaging = MPI)

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy with thallium-201 is frequently employed as a noninvasive test to evaluate abnormalities of myocardial perfusion in patients with established or suspected CAD. Myocardial uptake of thallium-201 chloride is proportional to regional myocardial blood flow and is dependent on the presence of viable myocardium. During exercise, the magnitude of the increase in blood flow to the nonischemic myocardial zones is greater than to the zones supplied by stenotic coronary arteries. Owing to this heterogeneous distribution of blood flow, the relative extraction of thallium by nonischemic myocardium is greater than that by ischemic myocardium.

During exercise thallium testing, the isotope is administered intravenously during peak exercise, and stress images are obtained immediately after discontinuation of exercise. These images reveal a decreased uptake by the ischemic myocardium, creating a perfusion defect. Redistribution images are obtained after 4 hours. Myocardium that was ischemic during stress but that is not ischemic at rest now extracts the isotope. Therefore, the perfusion defects during stress images are not observed in the rest images, and these reversible perfusion defects indicate the presence of viable myocardium. If the perfusion defects in stress images persist in the rest images, that is, if the perfusion defects are fixed, the myocardium is usually necrotic or fibrotic. A repeat injection of thallium and scanning 24 hours after stress can distinguish severely ischemic area from viable myocardium.

Thallium images may be planar or tomographic (single photon emission computed tomography=SPECT). The latter are more accurate and are therefore used more frequently to assess the presence and extent of ischemic and infarcted myocardium. In pooled analyses from multiple studies, exercise treadmill thallium myocardium scintigraphy has sensitivity for detecting CAD and specificity for excluding it of about 84% and 88%, respectively. The sensitivity approaches 90% with a quantitative computer-assisted analysis of the images without loss of specificity.

Considerable experience is required for the performance and interpretation of exercise thallium scintigraphy to achieve these high degrees of specificity and sensitivity.

Exercise thallium scintigraphy is less likely than exercise electrocardiography to provide false positive test results in women, but it may give false positive test results in patients with hypertrophic, dilated and infiltrative cardiomyopathies.

Like the exercise ECG, thallium stress scintigraphy is less sensitive in the diagnosis of single vessel disease, particularly of circumflex coronary artery stenosis, than in multi vessel coronary artery disease.

Technetium-99m, a calcium analog with a higher photon energy and a shorter half life than thallium chloride, can be linked to a variety of agents and used as a marker of myocardial perfusion. Technetium-99m-sestamibi is an isonitrile compound that, like thallium, is taken up by the myocardium proportional to blood flow but in contrast to thallium does not undergo redistribution. Tomographic images with technetium-99m also allow images to be acquired on the first pass through the ventricle and can be used to assess the left ventricular ejection fraction. However, as a noninvasive, less expensive and readily available test at more centers, echocardiography is usually preferable method for this purpose.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Echocardiographic and Nuclear Stress Testing (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography in patients with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD who have 1 of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

2. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography in patients with prior revascularization (either percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD and 1 of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

Class IIb1. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography in patients with a low or high probability of CAD who have 1 of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

2. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with a low or high probability of CAD and 1 of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

3. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography in patients with an intermediate probability of CAD who have 1 of the following:

4. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging, exercise echocardiography, adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging, or dobutamine echocardiography as the initial stress test in a patient with a normal rest ECG who is not taking digoxin. (Level of Evidence: B) 5. Exercise or dobutamine echocardiography in patients with left bundle-branch block. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

Perfusion Scintigraphy with Pharmacologic Stress

Many patients with known or suspected angina pectoris are unable to perform adequate exercise tests owing to peripheral vascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, diseases of the lower extremities, severe obesity, or deconditioning. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy during pharmacologic stress can be employed in these groups of patients.

Non endothelium dependent coronary vasodilators such as dipyridamole or adenosine can be used to increase flow to the non ischemic myocardial segments. During the test they produce perfusion defects in ischemic areas that can be detected by scintigraphy.

Alternatively, dobutamine can be used to increase heart rate and contractility, which increases myocardial oxygen demand, and this too may compromise perfusion of ischemic areas; the resultant ischemia can be detected by perfusion scintigraphy.

Dobutamine may cause true myocardial ischemia, not simply a relative increase in flow to nonischemic myocardium. Hence, it must be administered carefully with close monitoring and rapid cessation for potential symptomatic ischemia. All three of these pharmacologic stress tests have diagnostic accuracies (sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values) comparable with those of exercise perfusion scintigraphy.

Both dipyridamole and adenosine produce similar side effects, which consist of bronchospasm, flushing, dizziness, headache, nausea, atypical chest pain, and throat or jaw pain. Dipyridamole infusion has been reported to induce severe myocardial ischemia and, rarely, myocardial infarction. Adenosine, on the other hand, can produce significant bradyarrhythmias. Adenosine stress tests are therefore contraindicated in patients with atrioventricular block and sick sinus syndrome.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Cardiac Stress Imaging as the Initial Test for Diagnosis in Patients With Chronic Stable Angina Who Are Unable to Exercise (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography in patients with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Adenosine or dipyridamole stress myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography in patients with prior revascularization (either PTCA or CABG). (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIb1. Adenosine or dipyridamole stress myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography in patients with a low or high probability of CAD in the absence of electronically paced ventricular rhythm or left bundle-branch block. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with a low or high probability of CAD and 1 of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

|

” |

Echocardiography

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography is useful in the detection of ischemia induced regional wall motion abnormalities that occur at rest, during exercise or with pharmacologic stress testing. Upright treadmill exercise and supine bicycle ergometry, pacing, and pharmacologic stress, particularly with dobutamine, have been used in conjunction with two-dimensional echocardiography to detect regional wall motion abnormalities that most frequently occur during induced myocardial ischemia associated with CAD.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Echocardiography at Rest (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Patients with a systolic murmur suggestive of aortic stenosis and/or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Evaluation of extent (severity) of ischemia (eg, LV segmental wall motion abnormality) when the echocardiogram can be obtained during pain or within 30 minutes after its abatement. (Level of Evidence: C) Class IIb1. Patients with a click and/or murmur to diagnose mitral valve prolapse. (Level of Evidence: C) Class III1. Patients with a normal ECG, no history of MI, and no signs or symptoms suggestive of heart failure, valvular heart disease, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

Exercise echocardiography

This appears to be more sensitive and more specific and to have a higher predictive value than exercise electrocardiography. Exercise echocardiography has been reported to have a sensitivity of 74% to 100% and a specificity of 64% to 93% for detecting CAD.

Good agreement has also been reported between stress echocardiography and stress scintigraphy. With the use of high dose of dobutamine (up to 50 gm / kg / min), a method of dobutamine stress echocardiography can be performed with 86% to 96% of sensitivity and 66% to 95% of specificity.

Lower doses of dobutamine can also be used to detect hibernating myocardium. Areas of hibernating myocardium exhibit poor or absent contraction at rest but normal contraction during dobutamine infusion. By comparison, areas damaged by myocardial infarction or fibrosis exhibit no improvement with dobutamine.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Positron emission tomography can also assess regional coronary blood flow reserve, myocardial perfusion, and the presence and extent of hibernating myocardium. Rubidium-82 or ammonia (N13) are used for assessment of myocardial perfusion, whereas labeled carbohydrates such as fludeoxyglucose F-18, lipids, and some amino acids can be used to asses myocardial metabolism and viable ischemic myocardium.

With combined assessment of myocardial perfusion and metabolism, the sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CAD may approach 95%.

However, positron emission tomography is a very expensive noninvasive test and not readily available in every cardiology center. Its added value is principally in difficult situations in which myocardial perfusion by thallium scintigraphy and assessment of left ventricular systolic function by echocardiography or radionuclide ventriculography do not reveal the extent of hibernating myocardium.

Ambulatory ST Segment Monitoring

Many patients with CAD experience episodes of asymptomatic myocardial ischemia detectable by ST segment monitoring whether or not they have angina pectoris. Patients with symptomatic angina also often have multiple additional episodes of asymptomatic ischemia, and the frequency and severity of these episodes correlate with prognosis.

Although exercise or pharmacologic stress electrocardiography, perfusion scintigraphy or echocardiography is generally preferable to ambulatory ST segment monitoring in patients with effort angina, ambulatory ST segment monitoring is an alternative for patients who cannot exercise and is the preferred test in patients with suspected vasospastic angina that may not be provoked by effort or by pharmacologic agents such as dipyridamole, adenosine or dobutamine.

Ultrafast Computed Tomography = Electron Beam Tomography (EBT, EBCT)

Ultrafast computed tomography can be used to detect coronary calcifications, which often precede symptomatic coronary artery stenosis. However, coronary calcification is also observed in patients without important coronary disease at angiography. Although this test has generated substantial interest and publicity, its cist and the current lack of information from large scale assessments make it premature to recommend its use in routine clinical care.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMRI)

There are several approaches to detecting coronary artery disease using Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMRI). These include the visualization of the effects of induced ischemia (wall motion, perfusion) and direct visualization of coronary arteries (coronary angiography and flow). Early detection of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction is also possible (arterial wall imaging, brachial artery reactivity).

- Stress wall motion abnormalities

- Myocardial perfusion

- Coronary angiography and coronary flow evaluation

Coronary Angiography

The principal indication for coronary angiography in patients with stable angina pectoris with or without previous myocardial infarction is the consideration of coronary revascularization.

Occasionally, coronary angiography is recommended for diagnostic purposes because the patient’s clinical presentation and noninvasive test results are inconclusive. Even, if a vasospastic angina diagnosed by noninvasive studies, coronary angiography is indicated to determine whether a fixed coronary artery stenosis is present in addition to the spasm.

The indications for coronary angiography in patients with walk through angina, mixed angina, and postprandial angina are similar to those in patients with stable exertional angina.

It should be appreciated, however, that the demonstration of the presence of one or more critical coronary artery stenosis does not necessarily indicate that they are the cause of a chest pain syndrome. Furthermore, typical angina pectoris can occur in the absence of obstructive atherosclerotic CAD, thus raising the question of the presence of vasospastic angina, the metabolic syndrome X, or non ischemic causes of chest pain.

In general, a stenosis of 50% or more of the luminal diameter, which corresponds to a reduction of 70% or more of the cross sectional area, is considered significant coronary artery disease (CAD), since stenosis of this severity reduces coronary blood flow with exercise even though more severe stenosis are required to reduce flow at rest. A 70% stenosis of luminal diameter corresponds to a 90% cross-sectional area stenosis, and may result in angina at rest.

The extent of coronary artery disease (CAD) is often expressed in terms of the number of major epicardial coronary arteries with ≥50% diameter stenosis.

When the probability of severe angina is low, noninvasive tests are more appropriate. However, when the pretest probability is high, direct referral for coronary angiography is a suitable choice.

Coronary angiography is the most useful in the following situations:

- Exclude anatomical abnormalities in young patients as the cause of angina.

- Failure to make a definitive diagnosis after noninvasive tests

- Patients with suspected coronary artery spasm who require provocative tests

- Sudden cardiac death survivors

- Conditions causing inability to perform noninvasive tests.

- Probability of left main coronary artery stenosis or multi vessel disease.

- Occupational requirement for a firm diagnosis.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Coronary Angiography (DO NOT EDIT)[1]

| “ |

Class I1. Patients with known or possible angina pectoris who have survived sudden cardiac death. (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIa1. Patients with an uncertain diagnosis after noninvasive testing in whom the benefit of a more certain diagnosis outweighs the risk and cost of coronary angiography. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Patients who cannot undergo noninvasive testing due to disability, illness, or morbid obesity. (Level of Evidence: C) 3. Patients with an occupational requirement for a definitive diagnosis. (Level of Evidence: C) 4. Patients who by virtue of young age at onset of symptoms, noninvasive imaging, or other clinical parameters are suspected of having a nonatherosclerotic cause of myocardial ischemia (coronary artery anomaly, Kawasaki disease, primary coronary artery dissection, radiation-induced vasculoplasty). (Level of Evidence: C) 5. Patients in whom coronary artery spasm is suspected and provocative testing may be necessary. (Level of Evidence: C) 6. Patients with a high pretest probability of left main or 3-vessel CAD. (Level of Evidence: C) Class IIb1. Patients with recurrent hospitalization for chest pain in whom a definite diagnosis is judged necessary. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Patients with an overriding desire for a definitive diagnosis and a greater-than-low probability of CAD. (Level of Evidence: C) Class III1. Patients with significant comorbidity in whom the risk of coronary arteriography outweighs the benefit of the procedure. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Patients with an overriding personal desire for a definitive diagnosis and a low probability of CAD. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Coronary Angiography for Risk Stratification in Asymptomatic Patients (DO NOT EDIT)[2]

| “ |

Class IIa1. Patients with high-risk criteria that suggest ischemia on noninvasive testing. (Level of Evidence: C) Class IIb1. Patients with inadequate prognostic information after noninvasive testing. (Level of Evidence: C) Class III1. Patients who prefer to avoid revascularization. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

Test selection guideline for the individual basis

The exercise electrocardiography is the test of choice in patient with typical exertional angina with a normal resting ECG who is able to exercise. Even when the exercise ECG is not necessary to establish the diagnosis of CAD, it is very helpful in assessing its severity. If evidence for ischemia (by electrocardiography or by perfusion scintigraphy or echocardiography) is detected during the first stage of exercise, the likelihood of the presence of three-vessel disease or left main coronary artery stenosis is greater than if more exercise is required to provoke a positive test.

Exercise electrocardiography in patients with suspected or established stable angina pectoris is also useful to decide about nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic interventions.

In patients with stable angina pectoris, mixed angina, walk through angina, postprandial angina or patients without prior myocardial infarction, the exercise ECG is usually adequate to assess the presence and severity of myocardial ischemia.

The diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is established by the presence of typical anginal discomfort that is accompanied by ischemic changes on exercise ECG (or exercise or stress scintigraphy) with subsequent demonstration of the absence of critical coronary artery obstruction on coronary arteriography.

In women with typical angina, exercise ECG is also usually adequate. However, because of the higher incidence of false positive test results in stress ECG in women, exercise perfusion scintigraphy or echocardiography is a reasonable alternative and should also be considered.

Exercise perfusion scintigraphy should be considered as the test of choice when stress ECGs are uninterpretable, as in patients with (BBB) bundle branch block, interventricular conduction defects, left ventricular hypertrophy with baseline ST segment or T-wave abnormalities, pre excitation syndromes or ST segment changes owing to electrolyte imbalance or digitalis therapy. Stress perfusion scintigraphy is a more accurate method than the stress electrocardiography to determine the extent and distribution of ischemia.

In group of patients who are unable to exercise, adenosine or dipyridamole perfusion scintigraphy and dobutamine echocardiography are the preferred noninvasive tests to assess the presence and extent of myocardial ischemia. These are often recommended in patients with a blunted heart rate response because of antianginal therapy.

In patients with moderate or severe obstructive pulmonary airway diseases and poor exercise tolerance, dobutamine echocardiography is preferable diagnostic test to dipyridamole or adenosine scintigraphy.

Not all noninvasive or invasive tests that are available for the diagnosis of CAD and myocardial ischemia are applicable to all clinical subsets of patients with stable angina.

For patients with stable exertional angina, mixed angina, postprandial angina, walk-through angina, and nocturnal angina within 1 to 2 hours after the rest, it is desirable to select tests that are likely to induce myocardial ischemia by increasing myocardial oxygen requirements. In these patients, exercise ECG, exercise or stress perfusion scintigrahpy and echocardiography are designed to provoke ischemia.

In patients with stable angina pectoris, particularly those with documented prior myocardial infarction, assessment of left ventricular systolic function is necessary to select the appropriate therapy. In this group of patients, assessment for myocardial ischemia and ventricular function can be performed by the combination of a test for ischemia; exercise ECG and a LV function test (i.e., echocardiography at rest), or echocardiography both at rest and exercise.

ACC / AHA Guidelines- Noninvasive Testing for the Diagnosis of Obstructive CAD and Risk Stratification in Asymptomatic Patients (DO NOT EDIT)[2]

| “ |

Class IIb1. Exercise ECG testing without an imaging modality in asymptomatic patients with possible myocardial ischemia on ambulatory ECG (AECG) monitoring or with severe coronary calcification on EBCT in the absence of one of the following ECG abnormalities:

d. Complete left bundle-branch block. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Exercise perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography in asymptomatic patients with possible myocardial ischemia on AECG monitoring or with severe coronary calcification on EBCT who are able to exercise and have one of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

3. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with severe coronary calcification on EBCT but with one of the following baseline ECG abnormalities:

4. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography in patients with possible myocardial ischemia on AECG monitoring or with coronary calcification on EBCT who are unable to exercise. (Level of Evidence: C) 5. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography after exercise ECG testing in asymptomatic patients with an intermediate-risk or high-risk Duke treadmill score. (Level of Evidence: C) 6. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography after exercise ECG testing in asymptomatic patients with an inadequate exercise ECG. (Level of Evidence: C) Class III1. Exercise ECG testing without an imaging modality in asymptomatic patients with possible myocardial ischemia on AECG monitoring or with coronary calcification on EBCT but with the baseline ECG abnormalities listed under Class IIb1 above. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Exercise ECG testing without an imaging modality in asymptomatic patients with an established diagnosis of CAD owing to prior MI or coronary angiography; however, testing can assess functional capacity and prognosis. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Exercise or dobutamine echocardiography in asymptomatic patients with left bundle-branch block. (Level of Evidence: C) 4. Adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography in asymptomatic patients who are able to exercise and who do not have left bundle-branch block or electronically paced ventricular rhythm. (Level of Evidence: C) 5. Exercise myocardial perfusion imaging, exercise echocardiography, adenosine or dipyridamole myocardial perfusion imaging, or dobutamine echocardiography after exercise ECG testing in asymptomatic patients with a low-risk Duke treadmill score. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

See Also

Sources

- The ACC/AHA/ACP–ASIM Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina [1]

- TheACC/AHA 2002 Guideline Update for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina [2]

- The 2007 Chronic Angina Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina [3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Gibbons RJ, Chatterjee K, Daley J, et al. ACC/AHA/ACP–ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: executive summary and recommendations: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation. 1999; 99: 2829–2848. PMID 10351980

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, Ferguson TB Jr, Fihn SD, Fraker TD Jr, Gardin JM, O'Rourke RA, Pasternak RC, Williams SV, Gibbons RJ, Alpert JS, Antman EM, Hiratzka LF, Fuster V, Faxon DP, Gregoratos G, Jacobs AK, Smith SC Jr; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation. 2003 Jan 7; 107 (1): 149-58. PMID 12515758

- ↑ Fraker TD Jr, Fihn SD, Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, Ferguson TB Jr, Gardin JM, O'Rourke RA, Williams SV, Smith SC Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Group. 2007 chronic angina focused update of the ACC/AHA 2002 Guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Group to develop the focused update of the 2002 Guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina. Circulation. 2007 Dec 4; 116 (23): 2762-72. Epub 2007 Nov 12. PMID 17998462