Multiple sclerosis medical therapy

|

Multiple sclerosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Multiple sclerosis medical therapy On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Multiple sclerosis medical therapy |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Multiple sclerosis medical therapy |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [15]

Overview

Medical Therapy

Disease-modifying treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis:

Management of Acute Attacks

During symptomatic attacks administration of high doses of intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone,[1][2] is the routine therapy for acute relapses.The aim of this kind of treatment is to end the attack sooner and leave fewer lasting deficits in the patient. Although generally effective in the short term for relieving symptoms, corticosteroid treatments do not appear to have a significant impact on long-term recovery.[3] Potential side effects include osteoporosis[4] and impaired memory, being the latter reversible[5]

Disease Modifying Treatments

The earliest clinical presentation of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is the clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Several studies have shown that treatment with interferons during an initial attack can decrease the chance that a patient will develop MS.[6][7][8]

As of 2007, six disease-modifying treatments have been approved by regulatory agencies of different countries for relapsing-remitting MS. Three are interferons: two formulations of interferon beta-1a (trade names Avonex and Rebif) and one of interferon beta-1b (U.S. trade name Betaseron, in Europe and Japan Betaferon). A fourth medication is glatiramer acetate (Copaxone). The fifth medication, mitoxantrone, is an immunosuppressant also used in cancer chemotherapy. Finally, the sixth is natalizumab (marketed as Tysabri). All six medications are modestly effective at decreasing the number of attacks and slowing progression to disability, although they differ in their efficacy rate and studies of their long-term effects are still lacking.[9][10][11][12] Comparisons between immunomodulators (all but mitoxantrone) show that the most effective is natalizumab.[13] Mitoxantrone is probably the most effective of them all;[14] however, its use is limited by severe cardiotoxicity.[15]

Treatment of progressive MS is more difficult than relapsing-remitting MS. Mitoxantrone has shown positive effects in patients with a secondary progressive and progressive relapsing courses. It is moderately effective in reducing the progression of the disease and the frequency of relapses in patients in short-term follow-up.[12] On the other hand no treatment has been proven to modify the course of primary progresive MS.[16]

As with any medical treatment, these treatments have several adverse effects. One of the most common is irritation at the injection site. Interferons also produce symtoms similar to influenza; [17] while some patients taking glatiramer experience a post-injection reaction manifested by flushing, chest tightness, heart palpitations, breathlessness, and anxiety, which usually lasts less than thirty minutes.[10]. More dangerous are liver damage of interferons and mitoxantrone,[18][19][20] [21] the immunosuppressive effects and cardiac toxicity of the latter; [21] or the relation between natalizumab and some cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients who had taken it in combination with interferons.[22][23]

Medical management of few individual symptoms and/or signs is as follows :-

Bladder

Treatment objectives are alleviation of symptoms of urinary dysfunction, treatment of urinary infections, reduction of complicating factors and preservation of renal function. Treatments can be classified in two main subtypes: pharmacological and non pharmacological.

Pharmacological treatments vary greatly depending on the origin or type of dysfunction; however some examples of the medications used are:[24] alfuzosin for retention,[25] trospium and flavoxate for urgency and incontinency,[26][27] or desmopressin for nocturia.[28][29]

Non pharmacological treatments involve the use of pelvic floor muscle training, stimulation biofeedback, pessaries, bladder training, and sometimes intermittent catheterization.[30]

Cognition

Interferons have demonstrated that can help to reduce cognitive limitations in multiple sclerosis.[31]Anticholinesterase drugs such as donepezil commonly used in alzheimer disease; although not approved yet for multiple sclerosis; have also shown efficacy in different clinical trials.[32][33][34]

Fatigue

There are also different medications used to treat fatigue; such as amantadine,[35][36] or pemoline [37][38] as well as psychological interventions of energy conservation;[39][40] but the effects of all of them are small. For this reason fatigue is a very difficult symptom to manage.

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia

Different drugs as well as optic compensatory systems and prisms can be used to improve this symptoms.[41][42][43][44] Surgery can also be used in some cases for this problem.[45]

Optic Neuritis

Systemic intravenous treatment with corticosteroids, which may quicken the healing of the optic nerve, prevent complete loss of vision, and delay the onset of other symptoms, is often recommended.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Usually it's successfully treated with anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine[46] or phenytoin[47] but others such as gabapentin[48] can be used. [49]

Lhermittes's Sign and Dysesthesias

Both Lhermitte's sign and painful dysesthesias usually respond well to treatment with carbamazepine, clonazepam or amitriptyline.[50][51][52]

Spasticity

There is evidence, albeit limited, of the clinical effectiveness of baclofen,[53] dantrolene,[54] diazepam,[55] and tizanidine.[56][57][58] In the most complicated cases intrathecal injections of baclofen can be used.[59]

Transverse Myelitis

Treatment is usually symptomatic only, corticosteroids being used with limited success.

Tremor and Ataxia

In the treatment of tremor many medications have been proposed; however their efficacy is very limited. Medications that have been reported to provide some relief are isoniazid,[60][61][62][63] carbamazepine,[64] propranolol,[65][66][67] and gluthetimide,[68] but published evidence of effectiveness is very limited.[69]

-

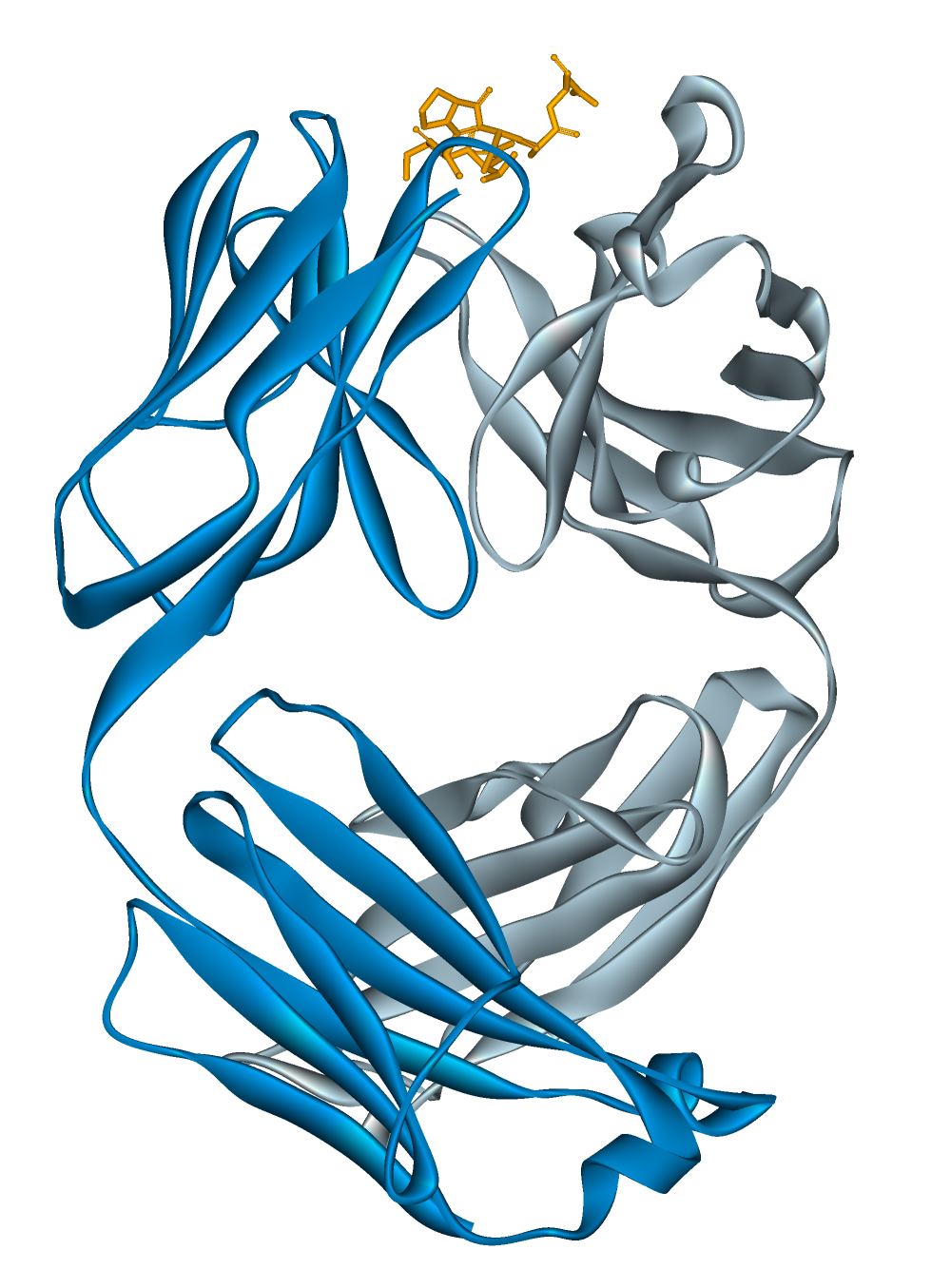

Chemical structure of alemtuzumab

-

Disease-modifying treatments are expensive and require frequent injections.

References

- ↑ Methylprednisolone Oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on2007-09-01.

- ↑ Methylprednisolone Sodium Succinate Injection. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-09-01.

- ↑ Brusaferri F, Candelise L (2000). "Steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials". J. Neurol. 247 (6): 435–42. PMID 10929272.

- ↑ Dovio A, Perazzolo L, Osella G; et al. (2004). "Immediate fall of bone formation and transient increase of bone resorption in the course of high-dose, short-term glucocorticoid therapy in young patients with multiple sclerosis". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (10): 4923–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0164. PMID 15472186.

- ↑ Uttner I, Müller S, Zinser C; et al. (2005). "Reversible impaired memory induced by pulsed methylprednisolone in patients with MS". Neurology. 64 (11): 1971–3. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000163804.94163.91. PMID 15955958.

- ↑ Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH; et al. (2000). "Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group". N Engl J Med. 343 (13): 898–904. PMID 11006365.

- ↑ Comi G, Filippi M, Barkhof F; et al. (2001). "Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomised study". Lancet. 357 (9268): 1576–82. PMID 11377645.

- ↑ Kappos L, Freedman MS, Polman CH; et al. (2007). "Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study". Lancet. 370 (9585): 389–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61194-5. PMID 17679016.

- ↑ Ruggieri M, Avolio C, Livrea P, Trojano M (2007). "Glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a review". CNS Drug Rev. 13 (2): 178–91. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00010.x. PMID 17627671.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Munari L, Lovati R, Boiko A (2004). "Therapy with glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD004678. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004678. PMID 14974077.

- ↑ Rice GP, Incorvaia B, Munari L; et al. (2001). "Interferon in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002002. PMID 11687131.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Martinelli Boneschi F, Rovaris M, Capra R, Comi G (2005). "Mitoxantrone for multiple sclerosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002127. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002127.pub2. PMID 16235298.

- ↑ Johnson KP (2007). "Control of multiple sclerosis relapses with immunomodulating agents". J. Neurol. Sci. 256 Suppl 1: S23–8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.060. PMID 17350652.

- ↑ Gonsette RE (2007). "Compared benefit of approved and experimental immunosuppressive therapeutic approaches in multiple sclerosis". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 8 (8): 1103–16. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.8.1103. PMID 17516874.

- ↑ Murray TJ (2006). "The cardiac effects of mitoxantrone: do the benefits in multiple sclerosis outweigh the risks?". Expert opinion on drug safety. 5 (2): 265–74. doi:10.1517/14740338.5.2.265. PMID 16503747.

- ↑ Leary SM, Thompson AJ (2005). "Primary progressive multiple sclerosis: current and future treatment options". CNS drugs. 19 (5): 369–76. PMID 15907149.

- ↑ Sládková T, Kostolanský F (2006). "The role of cytokines in the immune response to influenza A virus infection". Acta Virol. 50 (3): 151–62. PMID 17131933.

- ↑ Betaseron [package insert]. Montville, NJ: Berlex Inc; 2003

- ↑ Rebif [package insert]. Rockland, MA: Serono Inc; 2005.

- ↑ Avonex [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc; 2003

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Fox EJ (2006). "Management of worsening multiple sclerosis with mitoxantrone: a review". Clinical therapeutics. 28 (4): 461–74. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.013. PMID 16750460.

- ↑ Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis". N Engl J Med. 353 (4): 369–74. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051782. PMID 15947079. full text with registration

- ↑ Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D (2005). "Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab". N Engl J Med. 353 (4): 375–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051847. PMID 15947078. Free full text with registration

- ↑ Ayuso-Peralta L, de Andrés C (2002). "[Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis]". Revista de neurologia (in Spanish; Castilian). 35 (12): 1141–53. PMID 12497297.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on alfuzosin[1]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on trospium[2]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on flavoxate [3]

- ↑ Bosma R, Wynia K, Havlíková E, De Keyser J, Middel B (2005). "Efficacy of desmopressin in patients with multiple sclerosis suffering from bladder dysfunction: a meta-analysis". Acta Neurol. Scand. 112 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00431.x. PMID 15932348.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on desmopressin[4]

- ↑ Frances M Diro (2006) "Urological Management in Neurological Disease". [5]

- ↑ Montalban X, Rio J (2006). "Interferons and cognition". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 137–40. PMID 16626757.

- ↑ Christodoulou C, Melville P, Scherl W, Macallister W, Elkins L, Krupp L (2006). "Effects of donepezil on memory and cognition in multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 127–36. PMID 16626752.

- ↑ Porcel J, Montalban X (2006). "Anticholinesterasics in the treatment of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis". J Neurol Sci. 245 (1–2): 177–81. PMID 16674980.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on donepezil[6]

- ↑ Pucci E, Branãs P, D'Amico R, Giuliani G, Solari A, Taus C (2007). "Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD002818. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002818.pub2. PMID 17253480.

- ↑ Amantadine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Weinshenker BG, Penman M, Bass B, Ebers GC, Rice GP (1992). "A double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of pemoline in fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 42 (8): 1468–71. PMID 1641137.

- ↑ Pemoline. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P (2005). "Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis". Mult. Scler. 11 (5): 592–601. PMID 16193899.

- ↑ Matuska K, Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M (2007). "Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue". The American journal of occupational therapy. : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 61 (1): 62–9. PMID 17302106.

- ↑ Leigh RJ, Averbuch-Heller L, Tomsak RL, Remler BF, Yaniglos SS, Dell'Osso LF (1994). "Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology". Ann. Neurol. 36 (2): 129–41. PMID 8053648.

- ↑ Starck M, Albrecht H, Pöllmann W, Straube A, Dieterich M (1997). "Drug therapy for acquired pendular nystagmus in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 244 (1): 9–16. PMID 9007739.

- ↑ Clanet MG, Brassat D (2000). "The management of multiple sclerosis patients". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 13 (3): 263–70. PMID 10871249.

- ↑ Menon GJ, Thaller VT (2002). "Therapeutic external ophthalmoplegia with bilateral retrobulbar botulinum toxin- an effective treatment for acquired nystagmus with oscillopsia". Eye (London, England). 16 (6): 804–6. PMID 12439689.

- ↑ Jain S, Proudlock F, Constantinescu CS, Gottlob I (2002). "Combined pharmacologic and surgical approach to acquired nystagmus due to multiple sclerosis". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134 (5): 780–2. PMID 12429265.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on carbamazepine[7]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on phenytoin[8]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on gabapentin[9]

- ↑ Solaro C, Messmer Uccelli M, Uccelli A, Leandri M, Mancardi GL (2000). "Low-dose gabapentin combined with either lamotrigine or carbamazepine can be useful therapies for trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis". Eur. Neurol. 44 (1): 45–8. PMID 10894995.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on clonazepam[10]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on amitriptyline[11]

- ↑ Moulin DE, Foley KM, Ebers GC (1988). "Pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 38 (12): 1830–4. PMID 2973568.

- ↑ ;Baclofen oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Dantrolene oral. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2003-04-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Diazepam. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Tizanidine. US National Library of Medicine (Medline) (2005-07-01). Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2003). "Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 7 (40): iii, ix–x, 1–111. PMID 14636486.

- ↑ Paisley S, Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2002). "Clinical effectiveness of oral treatments for spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Mult. Scler. 8 (4): 319–29. PMID 12166503.

- ↑ Becker WJ, Harris CJ, Long ML, Ablett DP, Klein GM, DeForge DA (1995). "Long-term intrathecal baclofen therapy in patients with intractable spasticity". The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 22 (3): 208–17. PMID 8529173.

- ↑ Bozek CB, Kastrukoff LF, Wright JM, Perry TL, Larsen TA (1987). "A controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for action tremor in multiple sclerosis". J. Neurol. 234 (1): 36–9. PMID 3546605.

- ↑ Duquette P, Pleines J, du Souich P (1985). "Isoniazid for tremor in multiple sclerosis: a controlled trial". Neurology. 35 (12): 1772–5. PMID 3906430.

- ↑ Hallett M, Lindsey JW, Adelstein BD, Riley PO (1985). "Controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for severe postural cerebellar tremor in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 35 (9): 1374–7. PMID 3895037.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on Isoniazid [12]

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on carbamazepine [13]

- ↑ Koller WC (1984). "Pharmacologic trials in the treatment of cerebellar tremor". Arch. Neurol. 41 (3): 280–1. PMID 6365047.

- ↑ Sechi GP, Zuddas M, Piredda M, Agnetti V, Sau G, Piras ML, Tanca S, Rosati G (1989). "Treatment of cerebellar tremors with carbamazepine: a controlled trial with long-term follow-up". Neurology. 39 (8): 1113–5. PMID 2668787.

- ↑ Information from the USA National library of medicine on propanolol[14]

- ↑ Aisen ML, Holzer M, Rosen M, Dietz M, McDowell F (1991). "Glutethimide treatment of disabling action tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury". Arch. Neurol. 48 (5): 513–5. PMID 2021365.

- ↑ Mills RJ, Yap L, Young CA (2007). "Treatment for ataxia in multiple sclerosis". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD005029. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005029.pub2. PMID 17253537.