Acute intermittent porphyria

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Synonyms and keywords:

Overview

Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) is a rare metabolic disorder in the production of heme, the oxygen-binding prosthetic group of hemoglobin. Specifically, it is characterized by a deficiency of the enzyme porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) or hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS)[1]

Historical Perspective

One of the many hypothesized diagnoses of the artist Vincent van Gogh is that he and his siblings, particularly his brother Theo, suffered from AIP.[2] Another theorized sufferer was King George III of England, who even had a medallion struck to commemorate his "curing".

AIP makes an appearance on the television show House MD in season 1, episode 22 where Dr. House diagnoses his ex-wife's new husband with the disease.

It also makes an appearance on the television show Scrubs in season 4, episode 13 as a difficult to diagnose disease.

The TLC documentary drama mini-series, Mystery ER, features a landscaper with AIP who is repeatedly misdiagnosed.

Classification

AIP itself is a sub-category of diseases of broad group of disease describes as Porphyria.

Pathophysiology

AIP is an autosomal dominant disease with variable penetrance and expression. It is caused by variable mutation in gene encoding PBGD; it was earlier known as uroporphyrinogen I synthase. PBGD is present in hepatocytes as well Red Blood Cell.(RBC). It works in cytosol and converts porphobilinogen to porphobilingen deaminase. The PBGD is expressed in two forms depending on weather it is being expressed in hepatocytes or RBC. The manifestation of AIP typically occurs when production of PBGD is diminished or there is lack of expression gene encoding PBGD in hepatocytes.[3] PBGD enzyme deficiency alone is rarely symptomatic. The disease precipitates in the setting of another co-existing mutation as decrease in production of delta-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS1) or in the presence of other precipitating factor as mentioned below.

Causes

Genetic Causes: The most commonly seen precipitating factor is co-existence of deficiency of ALAS1 because of mutation in gene encoding ALAS1.

Drug Causes: The drugs which can precipitate AIP consist of following categories as described in the table.

| Anti-Hypertension Medications | Antimicrobials | Anti-epileptics[4] | Anesthetics | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine | Nitrofurantoin | Phenytoin | Etomidate | Alcohol[5] |

| Hydralazine | Rifampin | Phenobarbital | Ketamine | Diclofenac |

| Spiranolactone | Pyrazinamide | Carbamazepine | Thiopental | NSAIDs |

| Sulfa drugs | Oxycarbamazepine | Estrogen | ||

| Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole | Barbiturates | Progesterone | ||

| Griesofulvin | Clonazepam | Hydroxyzine | ||

| Ethosuximide | Tamoxifen | |||

| Valproate | Ergot derivatives | |||

| Smoking | ||||

| Carisoprodol | ||||

| Danazol | ||||

| Mebrobamate |

In females with AIP, attacks can be seen during luteal phase when progesterone levels are significantly elevated.

Contraindicated Medications:

The following medication are contraindicated with patients who have had a prior episode of AIP.

Barbiturates, Carbamazepine, Carisoprodol, Danazol, Diclofenac, Estrogen, Griesofulvin, Mebrobamate, Phenytoin, Phenobarbital, Primidone, Progeterone, Pyrazinamide, Rifampin, Sulfonamide, Valproate.

Differentiating Acute intermittent porphyria from other Diseases

The classical presentation of AIP is abdomen pain associated with other gastrointenstinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, constipation and rarely diarrhea.

In patients presenting with severe abdominal pain, pancreatitis should be ruled out by checking serum lipase and CT scan of abdomen. Also, other common etiologies such as hepatitis, acute gastroenteritis should be ruled out before considering AIP.

Other associated symptoms are neuropsychiatric manifestation of seizure, sensory loss, agitation, anxiety, hallucination, insomnia along with cardiac mainfestation of hypertension tachycardia. Other findings in some cases are respiratory paralysis, fever, generalized myalgia. Diagnosis of AIP is rare and should be pursued in the setting of high suspicion. When suspicion is high, urine porphyrins should be the first test of choice to be done.

In the setting of elevated urine porphyrins and abdomen pain, other possibility could be lead poisoning or hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 is possible.

In the setting of neurospychiatric manifestation and seizures, other differential which should be ruled out is Guillian-Barre syndrome, Herpes simplex virus encephalitis, lead poisoning, alcohol abuse, neurodegenerative diseases, paraneoplasituc syndromes, hyponatremia, infectious causes, drug abuse, and psychiatric illness.

Elevated levels of urinary prophobilinogen points towards diagnosis of AIP and further testing in this diagnosis should be pursued. If urinary prophobilinogen is normal and index of suspicion is high; then plasma poprhyrins level should be checked. If plasma poprhyrins comes out to be normal. AIP should be ruled out.[6] If plasma porphyrins level comes out to be elevated, further testing with plasma and fecal porphyrin should be done and this helps in differentiating types of porphyria.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Age: AIP manifests in the age group of 30-50 years but isolated case report have been reported prior to puberty and in the elderly as well.

Gender: The mutation is equally present in male and females. But, disease manifests more in the females in view of estrogen and progesterone being a natural risk factor for AIP.

Race: AIP is seen in all the races. Yet, more commonly in people of Northern European descent.

Risk Factors

The presence of mutation of gene PBGD in association with exposure to the medication mentioned above and co-existence of mutation or deficiency in ALAS1 is known to precipitate AIP.

Starvation and decreased intake of carbohydrate rich food can also exacerbate or precipitate AIP frequently.

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

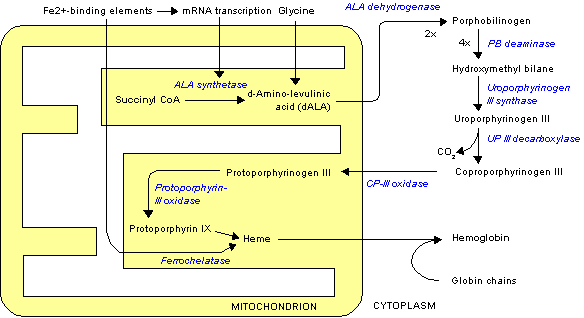

Normally, heme synthesis begins in the mitochondrion, proceeds into the cytoplasm, and finishes back in the mitochondrion. However, without PBGD, a necessary cytoplasmic enzyme, heme synthesis cannot finish, and the metabolite porphyrin accumulates in the cytoplasm. Most of the disease mainfests as AIP and isolated episodes. Some of these patients progress to chronic AIP.

Complications:

Patients living with chronic AIP present with intermittent attacks of AIP. These patients are prone to develop systemic hypertension, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease.[7]

Patients with age more than 50 and chronic AIP should be screened annually for hepatocellular carcinoma.[8][9]

Patients having prolonged attacks can end up having respiratory paralysis requiring mechanical ventilation.

Regular treatment with hemin can cause iron overload in patients and thus routine follow up of serum ferritin level is advised. In case serum ferritin level is elevated, phlebotomy is advised to prevent iron overload and its complications.

Prognosis:

There is no definite data regarding prognosis in AIP. A majority group of AIP remains undiagnosed and asymptomatic throughout there life. Patients who are managed well and they stay away from exacerbating factors have a good prognosis. When mortality occurs, it occurs mostly during the first episode of AIP or the subsequent episode.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

There is no specific diagnostic criteria established for AIP. A high index of suspicion in patients presenting with constellation of symptoms of abdominal pain, gastrointestinal symptoms and neusopsychiatric manifestations; urine porphobilinogen should be first test of choice.

Symptoms

The classical presentation of AIP is abdomen pain associated with other gastrointenstinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, constipation and rarely diarrhea. Abdomen pain is the most common presentation, and most of the time it is excruciating associated with cramping, nausea and vomiting.[6] But, it is not important for all symptoms to be present in every patient. Generalized pain involving chest, back, abdomen and extremities are also present in patients with AIP.

Other associated symptoms are neuropsychiatric manifestation of seizure, sensory loss, agitation, anxiety, hallucination, insomnia along with cardiac mainfestation of hypertension, tachycardia. Some cases present with respiratory paralysis, fever, generalized myalgia.[10] Some of these patients come with complaint of red colored urine or hematuria.

Patients who experience frequent attacks can develop chronic neuropathic pain in extremities as well as chronic pain in the gut. This is thought to be due to axonal nerve deterioration in affected areas of the nervous system. Some cases of chronic pain can be difficult to manage and may require treatment using multiple modalities. Depression often accompanies the disease and is best dealt with by treating the offending symptoms and if needed the judicious use of anti-depressants. Patient having chronic AIP are more predisposed to develop depression and chronic pain as well.

Physical Examination

Patients with AIP present with hypertension, tachycardia, and occasionally respiratory distress.

The most common finding is of abdominal tenderness. Occasionally finding of abdominal distention along with decreased bowel sounds suggestive of ileus is also seen.

Patients presenting with neuropychiatric manifestation of seizures are confused and stigmata of seizure such as tongue bite, frothing, urinary or fecal incontinence can be seen as well. Confusion, altered mental status, psychosis, agitation and hallucnination is also seen.

Laboratory Findings

Complete blood count is essentially normal or close to normal in a patient with AIP. Presence of abnormalities suggests of an alternative diagnosis.

The comprehensive metabolic panel shows hyponatremia in view of SIADH in some patients. Also, hypomagnesemia and hypercalcemia are occasionally seen. Liver transaminase is mildly elevated as well but synthetic functions of the liver are essentially normal. Elevated urea and creatinine can be seen in some patients who present with acute kidney injury or having chronic AIP showing Chronic kidney disease.

Plasma aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and porphobilinogen (PBG) levels are elevated during AIP attacks. These should be checked when the suspicion is high.

PBGD activity is decreased in Red Blood Cells in the active phase as well as the asymptomatic phase of AIP.[11][12]

DNA testing can be done to look for a mutation in PBGD to confirm the diagnosis of AIP, although it is not always required.[13]

Urine PBG is increased up to 20 to 200 mg/day in AIP; whereas the normal level is approximately 0 to 4 mg/day. Urinary ALA and porphyrins excretion are also increased. It is important to note that isolated urinary porphyrins excretion is non-specific and non-diagnostic of AIP.[6]

Fecal porphyrins levels are normal or slightly elevated in AIP.

Imaging Findings

CT scan and X-ray of abdomen may show distended bowel loops suggesting of ileus. Symptomatic management of ileus would be advised in these patients.

MRI Brain may reveal findings consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Neurology consultation would be beneficial in these patients.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Symptomatic Management: A high-carbohydrate diet is typically recommended; in severe attacks, a glucose 10% infusion is recommended, which may aid in recovery. If drugs have caused the attack, discontinuing the offending substances is essential.[6]

Infection is one of the top causes of attacks and requires vigorous treatment.

Pain is extremely severe and almost always requires the use of opiates to reduce it to tolerable levels. Pain should be treated early as medically possible due to its severity.

Nausea can be severe; it may respond to phenothiazine drugs but is sometimes intractable. Hot water baths/showers may lessen nausea temporarily but can present a risk of burns or falls.

Seizures, agitation, and psychosis should be managed with benzodiazepines. As mentioned above, most of the anti-epileptics exacerbate the symptoms of AIP.

Focused Management: Hemin is used for treatment of AIP in the United States whereas heme arginate is used in the United Kingdom.[14] Early administration of hemin or heme arginate can shorten the attack effect and duration of AIP. But, these provide symptomatic relief only and not curative. These inhibit ALA synthase, thus preventing of accumulation toxic precursors.

Hemin is a rarely used medication. In case a new diagnosis of AIP is made, the patient should be referred to centers capable of managing AIP or The American Porphyria Foundation should be contacted for quick procurement of the hemin.

Prior to administration of hemin, patients should be given carbohydrate loading of 400 gm/day of glucose for 1-2 days. Hemin is known to have potential interaction with multiple other medications. Thus, interactions and side effects should be closely monitored.

It is advised to expedite the lab work to confirm the diagnosis of AIP before starting focused management.

Future: A recently published phase 1 trial used Givosiran- a RNA interferance agent which inhibits hepatic ALAS1 showed decreased frequency of attacks in patients with recurrent AIP.[15]

Out of the box options: In developing countries, where hematin is not available, hemodialysis has been used as an alternative option.[16]

Secondary Prevention: An alert bracelet is recommended for all patients for all the patients who have known diagnosis of AIP for identification in case they develop acute attacks. An attack of AIP may be precipitated by one of the "four M's": medication, menstruation, malnutrition, maladies.

Surgery:

There is no surgical option available for treatment of AIP. In rare cases with frequent attacks of AIP; liver transplantation has been done in the past.

Prevention

Preventing exposure to the precipitating factors as mentioned in the causes section is known to prevent further attacks of AIP.

See also

Template:Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic pathology

References

- ↑ Jaramillo-Calle DA (2017). "Porphyria". N Engl J Med. 377 (21): 2100–1. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1712682. PMID 29182253.

- ↑ Arnold, Wilfred N. Vincent van Gogh: Chemicals, Crises, and Creativity, Birkhãuser, Boston, 1992. ISBN 0-8176-3616-1.

- ↑ Grandchamp B, Picat C, Kauppinen R, Mignotte V, Peltonen L, Mustajoki P; et al. (1989). "Molecular analysis of acute intermittent porphyria in a Finnish family with normal erythrocyte porphobilinogen deaminase". Eur J Clin Invest. 19 (5): 415–8. PMID 2511016.

- ↑ Louis CA, Sinclair JF, Wood SG, Lambrecht LK, Sinclair PR, Smith EL (1993). "Synergistic induction of cytochrome P450 by ethanol and isopentanol in cultures of chick embryo and rat hepatocytes". Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 118 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1006/taap.1993.1022. PMID 8441995.

- ↑ Thunell S, Floderus Y, Henrichson A, Moore MR, Meissner P, Sinclair J (1992). "Alcoholic beverages in acute porphyria". J Stud Alcohol. 53 (3): 272–6. PMID 1583906.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Kushner JP, Pierach CA, Pimstone NR; et al. (2005). "Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias". Ann Intern Med. 142 (6): 439–50. PMID 15767622.

- ↑ Tchernitchko D, Tavernier Q, Lamoril J, Schmitt C, Talbi N, Lyoumi S; et al. (2017). "A Variant of Peptide Transporter 2 Predicts the Severity of Porphyria-Associated Kidney Disease". J Am Soc Nephrol. 28 (6): 1924–1932. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016080918. PMC 5461799. PMID 28031405.

- ↑ Innala E, Andersson C (2011). "Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in acute intermittent porphyria: a 15-year follow-up in northern Sweden". J Intern Med. 269 (5): 538–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02335.x. PMID 21198994.

- ↑ Stewart MF (2012). "Review of hepatocellular cancer, hypertension and renal impairment as late complications of acute porphyria and recommendations for patient follow-up". J Clin Pathol. 65 (11): 976–80. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200791. PMID 22851509.

- ↑ Stein PE, Badminton MN, Rees DC (2017). "Update review of the acute porphyrias". Br J Haematol. 176 (4): 527–538. doi:10.1111/bjh.14459. PMID 27982422.

- ↑ Anderson KE, Sassa S, Peterson CM, Kappas A (1977). "Increased erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen-l-synthetase, delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and protoporphyrin in hemolytic anemias". Am J Med. 63 (3): 359–64. PMID 900140.

- ↑ Blum M, Koehl C, Abecassis J (1978). "Variations in erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen I synthetase activity in non porphyrias". Clin Chim Acta. 87 (1): 119–25. PMID 668133.

- ↑ Chen B, Solis-Villa C, Hakenberg J, Qiao W, Srinivasan RR, Yasuda M; et al. (2016). "Acute Intermittent Porphyria: Predicted Pathogenicity of HMBS Variants Indicates Extremely Low Penetrance of the Autosomal Dominant Disease". Hum Mutat. 37 (11): 1215–1222. doi:10.1002/humu.23067. PMC 5063710. PMID 27539938.

- ↑ Khanderia U (1986). "Circulatory collapse associated with hemin therapy for acute intermittent porphyria". Clin Pharm. 5 (8): 690–2. PMID 3742954.

- ↑ Sardh E, Harper P, Balwani M, Stein P, Rees D, Bissell DM; et al. (2019). "Phase 1 Trial of an RNA Interference Therapy for Acute Intermittent Porphyria". N Engl J Med. 380 (6): 549–558. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1807838. PMID 30726693.

- ↑ Prabahar MR, Manorajan R, Sathiyakumar D, Soundararajan P, Jayakumar M (2008). "Hemodialysis: a therapeutic option for severe attacks of acute intermittent porphyria in developing countries". Hemodial Int. 12 (1): 34–8. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2008.00237.x. PMID 18271838.

de:Akute intermittierende Porphyrie