COVID-19 laboratory findings: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Tests to be Performed for Patients Meeting COVID-19 Case Definition== | ==Tests to be Performed for Patients Meeting COVID-19 Case Definition== | ||

[[Image:COVID-19_-_Dx_testing.png|left|500px]] | |||

=== Antigen tests === | |||

Abbott BinaxNOW Ag Card detects the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein antigen but does not differentiate between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2.<ref>https://www.fda.gov/media/141570/download</ref> | |||

=== Molecular tests === | === Molecular tests === | ||

[[Molecular]] tests are used to diagnose active [[infection]] (presence of [[COVID-19]]) in people who are thought to be infected with [[COVID-19]] based on their clinical symptoms and having links to places where [[COVID-19]] has been reported. | [[Molecular]] tests are used to diagnose active [[infection]] (presence of [[COVID-19]]) in people who are thought to be infected with [[COVID-19]] based on their clinical symptoms and having links to places where [[COVID-19]] has been reported. | ||

[[Real-time polymerase chain reaction|Real-time reverse-transcription]] [[polymerase chain reaction]] (rRT-[[Polymerase chain reaction|PCR]]) assays are [[Molecule|molecular]] tests that can be used to detect [[viral]] [[RNA]] in clinical samples. | |||

=== Nucleic acid amplification test === | ==== Nucleic acid amplification test ==== | ||

* The importance of the need for confirmation of results of testing with pan-[[coronavirus]] primers is underscored by the fact that four human [[coronaviruses]] (HcoVs) are [[endemic]] globally: HCoV-229E, [[Human Coronavirus NL63|HCoV-NL63]], HCoV-HKU1 as well as HCoV-OC43. The latter two are betacoronaviruses. Two other betacoronaviruses that cause [[zoonotic]] infection in humans are [[MERS-CoV]], acquired by contact with dromedary camels and [[SARS]] arising from civets and cave-dwelling horseshoe bats. | * The importance of the need for confirmation of results of testing with pan-[[coronavirus]] primers is underscored by the fact that four human [[coronaviruses]] (HcoVs) are [[endemic]] globally: HCoV-229E, [[Human Coronavirus NL63|HCoV-NL63]], HCoV-HKU1 as well as HCoV-OC43. The latter two are betacoronaviruses. Two other betacoronaviruses that cause [[zoonotic]] infection in humans are [[MERS-CoV]], acquired by contact with dromedary camels and [[SARS]] arising from civets and cave-dwelling horseshoe bats. | ||

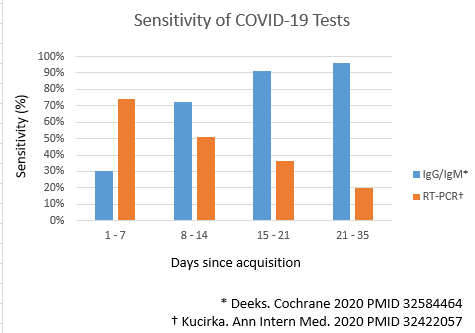

* The accuracy of nucleic acid amplification tests have been systematically reviewed<ref name="pmid32422057">{{cite journal| author=Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J| title=Variation in False-Negative Rate of Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based SARS-CoV-2 Tests by Time Since Exposure. | journal=Ann Intern Med | year= 2020 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=32422057 | doi=10.7326/M20-1495 | pmc=7240870 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32422057 }} </ref>. | |||

* PCR has been used to test salivary specimens<ref name="pmid32857487">{{cite journal| author=Wyllie AL, Fournier J, Casanovas-Massana A, Campbell M, Tokuyama M, Vijayakumar P | display-authors=etal| title=Saliva or Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. | journal=N Engl J Med | year= 2020 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=32857487 | doi=10.1056/NEJMc2016359 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32857487 }} </ref><ref name="pmid32857591">{{cite journal| author=Caulley L, Corsten M, Eapen L, Whelan J, Angel JB, Antonation K | display-authors=etal| title=Salivary Detection of COVID-19. | journal=Ann Intern Med | year= 2020 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=32857591 | doi=10.7326/M20-4738 | pmc=7470212 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32857591 }} </ref>. | |||

=== Serological testing === | === Serological testing === | ||

| Line 24: | Line 31: | ||

*[[Serological testing|Serological]] testing may be useful to confirm immunologic response to a pathogen from a specific [[viral]] group, e.g. [[coronavirus]]. | *[[Serological testing|Serological]] testing may be useful to confirm immunologic response to a pathogen from a specific [[viral]] group, e.g. [[coronavirus]]. | ||

* Best results from [[Serological testing|serologic]] testing requires the collection of paired [[serum]] samples (in the acute and [[convalescent]] phase) from cases under investigation. | * Best results from [[Serological testing|serologic]] testing requires the collection of paired [[serum]] samples (in the acute and [[convalescent]] phase) from cases under investigation. | ||

* The accuracy of serologic tests have been systematically reviewed<ref name="pmid32584464">{{cite journal| author=Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Spijker R, Taylor-Phillips S | display-authors=etal| title=Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. | journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev | year= 2020 | volume= 6 | issue= | pages= CD013652 | pmid=32584464 | doi=10.1002/14651858.CD013652 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32584464 }} </ref><ref name="pmid32611558">{{cite journal| author=Lisboa Bastos M, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, Campbell JR, Haraoui LP, Johnston JC | display-authors=etal| title=Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. | journal=BMJ | year= 2020 | volume= 370 | issue= | pages= m2516 | pmid=32611558 | doi=10.1136/bmj.m2516 | pmc=7327913 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32611558 }} </ref>. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" align="left" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

! colspan="3" |Tests to be performed for patients meeting case definition | ! colspan="3" |Tests to be performed for patients meeting case definition | ||

| Line 71: | Line 79: | ||

* [[COVID-19-associated lymphopenia|Lymphocytopenia]] | * [[COVID-19-associated lymphopenia|Lymphocytopenia]] | ||

* Increase in monocyte distribution width (MDW) | * Increase in [[monocyte distribution width]] (MDW) | ||

**MDW was found to be increased in all patients with COVID-19 infection, particularly in those with the worst conditions.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | |||

*MDW was found to be increased in all patients with COVID-19 infection, particularly in those with the worst conditions.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | |||

* [[Thrombocytosis]] | * [[Thrombocytosis]] | ||

| Line 90: | Line 97: | ||

*Increased [[Interleukin 6|IL-6]] | *Increased [[Interleukin 6|IL-6]] | ||

**Increase in [[IL-6]] has been reported to be associated with death in COVID-19 infection.<ref name="pmid32167524" /> | **Increase in [[IL-6]] has been reported to be associated with death in COVID-19 infection.<ref name="pmid32167524" /> | ||

**Increased level of [[Interleukin 6|IL-6]] is an indicator of [[COVID-19-associated cytokine storm]]. | |||

* Increased [[procalcitonin]] | * Increased [[procalcitonin]] | ||

| Line 97: | Line 105: | ||

* Increased [[ferritin]] | * Increased [[ferritin]] | ||

**There have been different reports regarding the association of increase in [[ferritin]] with death in COVID-19 infection; for example, there has been a report that increase in [[ferritin]] is associated with [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)]] but not death<ref name="pmid32167524">{{cite journal| author=Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S | display-authors=etal| title=Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. | journal=JAMA Intern Med | year= 2020 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=32167524 | doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 | pmc=7070509 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32167524 }} </ref>, while another one reports an association between increase in [[ferritin]] and death in COVID-19 infection<ref name="pmid32171076">{{cite journal| author=Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z | display-authors=etal| title=Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. | journal=Lancet | year= 2020 | volume= 395 | issue= 10229 | pages= 1054-1062 | pmid=32171076 | doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 | pmc=7270627 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32171076 }} </ref | **There have been different reports regarding the association of increase in [[ferritin]] with death in COVID-19 infection; for example, there has been a report that increase in [[ferritin]] is associated with [[Acute respiratory distress syndrome|acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)]] but not death<ref name="pmid32167524">{{cite journal| author=Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S | display-authors=etal| title=Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. | journal=JAMA Intern Med | year= 2020 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=32167524 | doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 | pmc=7070509 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32167524 }} </ref>, while another one reports an association between increase in [[ferritin]] and death in COVID-19 infection.<ref name="pmid32171076">{{cite journal| author=Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z | display-authors=etal| title=Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. | journal=Lancet | year= 2020 | volume= 395 | issue= 10229 | pages= 1054-1062 | pmid=32171076 | doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 | pmc=7270627 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=32171076 }} </ref> | ||

* Decreased | *Decreased [[albumin]] | ||

**As a negative acute‐phase reactant, circulatory level of albumin may fall as a result of increased transcapillary leakage or reduced hepatic synthesis mediated by inflammatory cytokines such as | **As a negative acute‐phase reactant, circulatory level of albumin may fall as a result of increased transcapillary leakage or reduced hepatic synthesis mediated by inflammatory cytokines such as [[IL-6|interleukin‐6]] and [[tumor necrosis factor alpha]]. <ref name="ChiGibson2019">Chi, Gerald; Gibson, C. Michael; Liu, Yuyin; Hernandez, Adrian F.; Hull, Russell D.; Cohen, Alexander T.; Harrington, Robert A.; Goldhaber, Samuel Z. (2019). "Inverse relationship of serum albumin to the risk of venous thromboembolism among acutely ill hospitalized patients: Analysis from the APEX trial". American Journal of Hematology. 94 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1002/ajh.25296. ISSN 0361-8609.</ref>Consequently, [[hypoalbuminemia]] may indicate a hyperinflammatory status associated with [[COVID-19]]. | ||

</ref> Consequently, [[hypoalbuminemia]] may indicate a hyperinflammatory status associated with [[COVID-19]]. | **[[Albumin]] may be decreased in many conditions such as [[sepsis]], renal disease or [[malnutrition]].<ref name="pmid32311826" /> | ||

**In patients with COVID-19 infection, decrease in [[albumin]] may indicate liver function abnormality.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | |||

=== Liver Function Tests === | === Liver Function Tests === | ||

| Line 106: | Line 115: | ||

* Increased [[Aspartate aminotransferase|aspartate aminotrasnferase]] ([[Aspartate transaminase|AST]]): | * Increased [[Aspartate aminotransferase|aspartate aminotrasnferase]] ([[Aspartate transaminase|AST]]): | ||

**Increase in [[Aspartate transaminase|AST]] is seen in 39.4% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 18.2% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | **Increase in [[Aspartate transaminase|AST]] is seen in 39.4% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 18.2% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | ||

*In patients with [[COVID-19]] infection, increase in [[aminotransferases]] may indicate injury to the [[liver]] or multi-system damage.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | **In patients with [[COVID-19]] infection, increase in [[aminotransferases]] may indicate injury to the [[liver]] or multi-system damage.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | ||

* Increased [[alanine aminotransferase]] ([[Alanine transaminase|ALT]]): | * Increased [[alanine aminotransferase]] ([[Alanine transaminase|ALT]]): | ||

**Increase in [[ALT]] is seen in 28.1% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 19.8% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | **Increase in [[ALT]] is seen in 28.1% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 19.8% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | ||

| Line 113: | Line 122: | ||

*Increase in total [[bilirubin]] | *Increase in total [[bilirubin]] | ||

**Increase in total bilirubin is seen in 13.3% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 9.9% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | **Increase in total bilirubin is seen in 13.3% of patients with severe [[COVID-19]] infection compared to 9.9% of patients with non-severe infection.<ref name="pmid32109013" /> | ||

**Bilirubin | **Bilirubin is produced by liver cells and increases in liver and biliary conditions.<ref name="pmid32311826" /> | ||

**In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in total bilirubin may indicate injury to the liver.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | **In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in total bilirubin may indicate injury to the liver.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | ||

| Line 135: | Line 144: | ||

**LDH is expressed in almost all cells and an increase in [[LDH]] could be seen in damage to any of the cell types.<ref name="pmid32311826" /> | **LDH is expressed in almost all cells and an increase in [[LDH]] could be seen in damage to any of the cell types.<ref name="pmid32311826" /> | ||

**In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in [[Lactate dehydrogenase|LDH]] may indicate injury to the lungs or multi-system damage.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | **In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in [[Lactate dehydrogenase|LDH]] may indicate injury to the lungs or multi-system damage.<ref name="pmid32191623" /> | ||

* Increased [[Creatine kinase|creatine kinase]] | * Increased [[Creatine kinase|creatine kinase]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

Latest revision as of 13:27, 1 April 2023

For COVID-19 frequently asked inpatient questions, click here

For COVID-19 frequently asked outpatient questions, click here

|

COVID-19 Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

COVID-19 laboratory findings On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of COVID-19 laboratory findings |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for COVID-19 laboratory findings |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Syed Hassan A. Kazmi BSc, MD [2] Shakiba Hassanzadeh, MD[3]

Overview

Laboratory tests can be done to confirm whether illness may be caused by human coronaviruses. Specific laboratory tests include serology for viral antigen, molecular testing and viral culture. All these tests can be used to confirm infection with coronavirus. Non-specific laboratory findings in COVID-19 include lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated C-Reactive protein, elevated liver function tests (ALT, AST), increased creatine kinase, increased D-Dimer and an increase in the levels of markers of cell damage e.g. troponin, lactate dehydrogenase, interleukin-4, procalcitonin.

Tests to be Performed for Patients Meeting COVID-19 Case Definition

Antigen tests

Abbott BinaxNOW Ag Card detects the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein antigen but does not differentiate between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2.[1]

Molecular tests

Molecular tests are used to diagnose active infection (presence of COVID-19) in people who are thought to be infected with COVID-19 based on their clinical symptoms and having links to places where COVID-19 has been reported.

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assays are molecular tests that can be used to detect viral RNA in clinical samples.

Nucleic acid amplification test

- The importance of the need for confirmation of results of testing with pan-coronavirus primers is underscored by the fact that four human coronaviruses (HcoVs) are endemic globally: HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1 as well as HCoV-OC43. The latter two are betacoronaviruses. Two other betacoronaviruses that cause zoonotic infection in humans are MERS-CoV, acquired by contact with dromedary camels and SARS arising from civets and cave-dwelling horseshoe bats.

- The accuracy of nucleic acid amplification tests have been systematically reviewed[2].

- PCR has been used to test salivary specimens[3][4].

Serological testing

- Serological testing may be useful to confirm immunologic response to a pathogen from a specific viral group, e.g. coronavirus.

- Best results from serologic testing requires the collection of paired serum samples (in the acute and convalescent phase) from cases under investigation.

- The accuracy of serologic tests have been systematically reviewed[5][6].

| Tests to be performed for patients meeting case definition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Test | Source of Specimen | Additional Comments |

| In laboratories that have validated broad coronavirus RT-PCR

assays it is advised to check the primers against the published 2019-nCoV sequence and check if primers are overlapping and have the capacity to detect the 2019-nCoV. On a positive results sequencing should be performed to determine the precise virus detected (e.g. on an amplicon of a non-conserved region). |

Respiratory secretions | Collect on presentation. Done by an expert laboratory. |

| NAAT for 2019n-CoV when it becomes available (assays currently under validation) | Respiratory secretions | Collect on presentation. Done by an expert laboratory until validation has been finalized. |

| Serology, broad corona virus serology on paired samples if available. | Respiratory secretions | Paired samples necessary for confirmation, the first sample collected in week 1 of illness, and the second collected 3-4 weeks later. If a single serum sample can be collected, collect at least 3 weeks after onset of symptoms. Done by the expert laboratory until more information on the performance of available assays. |

Laboratory Findings

Complete Blood Count

Complete blood count may show the following:

- Leukocytosis

- Leukocytosis is seen in 11.4% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 4.8% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, leukocytosis may be an indication of a bacterial infection or superinfection.[8]

- Increase in monocyte distribution width (MDW)

- MDW was found to be increased in all patients with COVID-19 infection, particularly in those with the worst conditions.[8]

- Thrombocytosis

- Thrombocytosis has been reported in 4% of patients with COVID-19 infection.[9]

Acute Phase Reactants

The following inflammatory markers may be altered:

- Increased C-reactive protein

- Increase in CRP is seen in 81.5% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 56.4% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- CRP is an acute phase reactant that increases in conditions with inflammation.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in CRP may be an indication of severe viral infection or sepsis and viremia.[8]

- Increased IL-6

- Increase in IL-6 has been reported to be associated with death in COVID-19 infection.[11]

- Increased level of IL-6 is an indicator of COVID-19-associated cytokine storm.

- Increased procalcitonin

- Increase in procalcitonin is seen in 13.7% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 3.7% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- In sepsis, the activation and adherence of monocytes increase procalcitonin, therefore procalcitonin in a biomarker for sepsis and septic shock.[12]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in procalcitonin may be an indication of bacterial infection or superinfection.[8]

- Increased ferritin

- There have been different reports regarding the association of increase in ferritin with death in COVID-19 infection; for example, there has been a report that increase in ferritin is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) but not death[11], while another one reports an association between increase in ferritin and death in COVID-19 infection.[13]

- Decreased albumin

- As a negative acute‐phase reactant, circulatory level of albumin may fall as a result of increased transcapillary leakage or reduced hepatic synthesis mediated by inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‐6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. [14]Consequently, hypoalbuminemia may indicate a hyperinflammatory status associated with COVID-19.

- Albumin may be decreased in many conditions such as sepsis, renal disease or malnutrition.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, decrease in albumin may indicate liver function abnormality.[8]

Liver Function Tests

The following abnormalities may be observed on LFTs:

- Increased aspartate aminotrasnferase (AST):

- Increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT):

- Increase in ALT is seen in 28.1% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 19.8% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- ALT is produced by liver cells and is increased in liver conditions.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in aminotransferases may indicate injury to the liver or multi-system damage.[8]

- Increase in total bilirubin

- Increase in total bilirubin is seen in 13.3% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 9.9% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- Bilirubin is produced by liver cells and increases in liver and biliary conditions.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in total bilirubin may indicate injury to the liver.[8]

Renal Function Tests

Renal function tests may show the following:

- Increased BUN

- Increased creatinine

- Increase in creatinine is seen in 4.3% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 1% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- Creatinin is produced in the liver and excreted by the kidneys; creatinine increases when there is decrease in glomerular filtration rate.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in creatinine may indicate injury to the kidneys.[8]

Markers of Cell Damage

The following markers of cellular damage may be altered:

- Increased troponin

- In myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome are used for diagnosis.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in cardiac troponins may indicate cardiac injury.[8]

- Increased myoglobin

- Increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Increase in LDH is seen in 58.1% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection compared to 37.2% of patients with non-severe infection.[7]

- LDH is expressed in almost all cells and an increase in LDH could be seen in damage to any of the cell types.[10]

- In patients with COVID-19 infection, increase in LDH may indicate injury to the lungs or multi-system damage.[8]

- Increased creatine kinase

References

- ↑ https://www.fda.gov/media/141570/download

- ↑ Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J (2020). "Variation in False-Negative Rate of Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based SARS-CoV-2 Tests by Time Since Exposure". Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M20-1495. PMC 7240870 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32422057 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Wyllie AL, Fournier J, Casanovas-Massana A, Campbell M, Tokuyama M, Vijayakumar P; et al. (2020). "Saliva or Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens for Detection of SARS-CoV-2". N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2016359. PMID 32857487 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Caulley L, Corsten M, Eapen L, Whelan J, Angel JB, Antonation K; et al. (2020). "Salivary Detection of COVID-19". Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M20-4738. PMC 7470212 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32857591 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Spijker R, Taylor-Phillips S; et al. (2020). "Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6: CD013652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013652. PMID 32584464 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Lisboa Bastos M, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, Campbell JR, Haraoui LP, Johnston JC; et al. (2020). "Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 370: m2516. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2516. PMC 7327913 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32611558 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX; et al. (2020). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". N Engl J Med. 382 (18): 1708–1720. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. PMC 7092819 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32109013 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Lippi G, Plebani M (2020). "The critical role of laboratory medicine during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other viral outbreaks". Clin Chem Lab Med. 58 (7): 1063–1069. doi:10.1515/cclm-2020-0240. PMID 32191623 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y; et al. (2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMC 7135076 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32007143 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Frater JL, Zini G, d'Onofrio G, Rogers HJ (2020). "COVID-19 and the clinical hematology laboratory". Int J Lab Hematol. 42 Suppl 1: 11–18. doi:10.1111/ijlh.13229. PMC 7264622 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32311826 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S; et al. (2020). "Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China". JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. PMC 7070509 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32167524 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Meisner M (2014). "Update on procalcitonin measurements". Ann Lab Med. 34 (4): 263–73. doi:10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.263. PMC 4071182. PMID 24982830.

- ↑ Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z; et al. (2020). "Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study". Lancet. 395 (10229): 1054–1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. PMC 7270627 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32171076 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Chi, Gerald; Gibson, C. Michael; Liu, Yuyin; Hernandez, Adrian F.; Hull, Russell D.; Cohen, Alexander T.; Harrington, Robert A.; Goldhaber, Samuel Z. (2019). "Inverse relationship of serum albumin to the risk of venous thromboembolism among acutely ill hospitalized patients: Analysis from the APEX trial". American Journal of Hematology. 94 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1002/ajh.25296. ISSN 0361-8609.