Meningioma pathophysiology

|

Meningioma Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Meningioma pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Meningioma pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Meningioma pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Haytham Allaham, M.D. [2]

Overview

Pathogenesis

Meningioma arise from arachnoidal cells, most of which are near the vicinity of the venous sinuses, and this is the site of greatest prevalence for meningioma formation. They are most frequently attached to the dura over the superior parasagittal surface of frontal and parietal lobes, along the sphenoid ridge, in the olfactory grooves, the sylvian region, superior cerebellum along the falx cerebri, cerebellopontine angle, and the spinal cord. The tumor is usually gray, well-circumscribed, and takes on the form of space it occupies. They are usually dome-shaped, with the base lying on the dura.

Meningiomas are the most common benign tumors of the brain (95% of benign tumors), rare meningioma can be malignant. It arises from the meninges which surround the brain and spinal cord. A small meningioma causes no significant signs. With the development of the lump, frequent symptoms include changes in vision, for example seeing double or blurriness, headache, hearing loss memory loss, etc. A meningioma doesn't always require immediate treatment. Treatments include surgery, radiation and a combination of them.

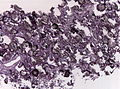

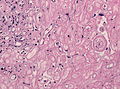

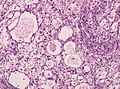

Histologically, the cells are relatively uniform, with a tendency to encircle one another, forming whorls and psammoma bodies (laminated calcific concretions). They have a tendency to calcify and are highly vascularized.

Genetics

Gross Pathology

Microscopic Pathology

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, whorled appearance, calcification, and psammoma bodies are characteristic findings of of meningioma.

- The table below differentiates between the three main groups of multiple myeloma according to WHO histological classification:

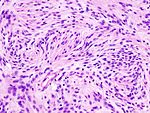

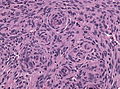

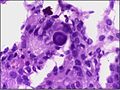

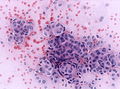

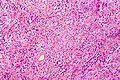

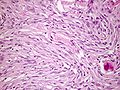

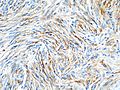

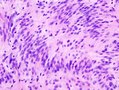

- Shown below is a series of microscopic images featuring specific findings seen in each subtype of meningioma:

-

Meningothelial meningioma with syncytial appearance and whorl formations

-

Meningothelial meningioma with psammoma body

-

Meningothelial meningioma with onion bulb formation in smear

-

Meningothelial meningioma Meningioma HPS stain

-

Fibrous meingioma with spindle cells in parallel bundles with few to none whorl formations.

-

Fibrous meingioma EMA staining

-

Transitional meingioma with lobular and fasicular growth patterns coexist

-

Psammomatous meningioma with numerous psammoma bodies

-

Angiomatousmeningioma where hyalinized vessels dominate over tumor cells degenerative nuclear atypia

-

Microcystic meningioma with cystic appearance and increased cytologic pleomorphism of the elongated cells