Mastitis pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

Prince Djan (talk | contribs) |

Prince Djan (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

* Autoimmune reaction to luminal fluid. | * Autoimmune reaction to luminal fluid. | ||

Approximately a quarter of patients may be [[hyperprolactinemia|hyperprolactinemic]]. There have been strong association with [[fibrocystic breast disease|fibrocystic condition]] and [[thyroid]] conditions. Up to half of patients may experience transient [[hyperprolactinemia]] possibly caused by [[inflammation]] or treatment and significant number may have abnormally high [[Prolactin]] reserve.<ref name="pmid2918655">{{cite journal| author=Peters F, Schuth W| title=Hyperprolactinemia and nonpuerperal mastitis (duct ectasia). | journal=JAMA | year= 1989 | volume= 261 | issue= 11 | pages= 1618-20 | pmid=2918655 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=2918655 }} </ref> <ref name="pmid26179543">{{cite journal| author=Kutsuna S, Mezaki K, Nagamatsu M, Kunimatsu J, Yamamoto K, Fujiya Y et al.| title=Two Cases of Granulomatous Mastitis Caused by Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii Infection in Nulliparous Young Women with Hyperprolactinemia. | journal=Intern Med | year= 2015 | volume= 54 | issue= 14 | pages= 1815-8 | pmid=26179543 | doi=10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4254 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=26179543 }} </ref> | |||

[[ | [[TSH]], [[Prolactin]], and [[IGF-1]] are important sytemic factors in galactopoiesis. The significance of these factors in secretory disease is not well documented but it has been asserted that the mechanisms of secretory disease and galactopoiesis are closely related. | ||

Alveolar and ductal [[epithelia]] permeability is mostly controlled by tight junction regulation and is closely linked to galactopoiesis and secretory disease. The tight junctions are regulated by a multitude of systemic (prolactin, [[progesterone]], [[glucocorticoid]]s) and local (intramammary pressure, [[TGF-beta]], [[osmotic]] balance) factors. | |||

Current smokers have the worst [[prognosis]] and highest rate of recurrent [[abscess]]es.<ref name="pmid20727287">{{cite journal| author=Risager R, Bentzon N| title=[Smoking and increased risk of mastitis]. | journal=Ugeskr Laeger | year= 2010 | volume= 172 | issue= 33 | pages= 2218-21 | pmid=20727287 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20727287 }} </ref> | Current smokers have the worst [[prognosis]] and highest rate of recurrent [[abscess]]es.<ref name="pmid20727287">{{cite journal| author=Risager R, Bentzon N| title=[Smoking and increased risk of mastitis]. | journal=Ugeskr Laeger | year= 2010 | volume= 172 | issue= 33 | pages= 2218-21 | pmid=20727287 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20727287 }} </ref> | ||

Revision as of 01:49, 19 September 2016

|

Mastitis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Mastitis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Mastitis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Mastitis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Prince Tano Djan, BSc, MBChB [2]

Overview

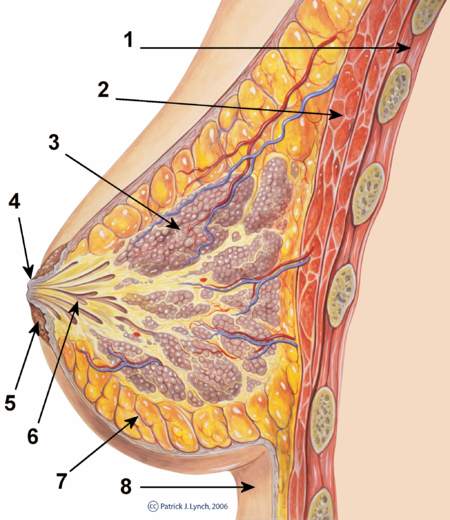

Most clinically significant cases of nonpeurperal mastitis start as inflammation of the ductal and lobular system (galactophoritis) and possibly the immediately surrounding tissue (refer to the image below). Development of Nonpeurperal mastitis is the result of Secretory stasis whereas Peurperal mastitis occurs when bacteria, often from patients skin or the baby's mouth/nostrils [1] enters a milk duct through a crack in the nipple.

-

cross-section of the breast

1. Chest wall 2. Pectoralis muscles 3. Lobules 4. Nipple 5. Areola 6. Milk duct 7. Fatty tissue 8. Skin

-

surface anatomy of the breast

Pathophysiology

Nonpuerperal Mastitis: Pathogenesis

Most clinically significant cases of nonpeurperal mastitis start as inflammation of the ductal and lobular system (galactophoritis) and possibly the immediately surrounding tissue. Development of Peurperal mastitis occurs when bacteria, often from patients skin or the baby's mouth/nostrils [2] enters a milk duct through a crack in the nipple.

Development of Nonpeurperal mastitis is the result of Secretory stasis about 80% of cases. The retained secretions can get infected or lead to inflammation by causing mechanical injury leading to leakage of the lactiferous ducts. Autoimmune reaction to the secretions may also be a factor.

Peurperal Mastitis: Pathogenesis

Development of Peurperal mastitis occurs when bacteria, often from patients skin or the baby's mouth/nostrils [3] enters a milk duct through a crack in the nipple.

Several mechanisms are thought to lead to the pathogenesis of mastitis as shown below:

- Secretory disease or galactorrhea.

- Changes in permeability of lactiferous ducts (retention syndrome).

- Blockage of lactiferous ducts, for example duct plugging caused by squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts.

- Trauma, injury.

- Mechanical irritation caused by retention syndrome or Fibrocystic Condition.

- Infection.

- Autoimmune reaction to luminal fluid.

Approximately a quarter of patients may be hyperprolactinemic. There have been strong association with fibrocystic condition and thyroid conditions. Up to half of patients may experience transient hyperprolactinemia possibly caused by inflammation or treatment and significant number may have abnormally high Prolactin reserve.[4] [5]

TSH, Prolactin, and IGF-1 are important sytemic factors in galactopoiesis. The significance of these factors in secretory disease is not well documented but it has been asserted that the mechanisms of secretory disease and galactopoiesis are closely related.

Alveolar and ductal epithelia permeability is mostly controlled by tight junction regulation and is closely linked to galactopoiesis and secretory disease. The tight junctions are regulated by a multitude of systemic (prolactin, progesterone, glucocorticoids) and local (intramammary pressure, TGF-beta, osmotic balance) factors.

Current smokers have the worst prognosis and highest rate of recurrent abscesses.[6]

Acromegaly may present with symptoms of non-puerperal mastitis.

Microscopic pathology

Histopathology of granulomatous mastitis shows characteristic distribution of granulomatous inflammation which remains the gold standard for diagnosis.[7]

Histologically Lupus matitis is seen as lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and hyaline sclerosis of the adipose tissue. Treatment is primarily medical due to exacerbation of disease by surgical intervention. This histologic finding is required to make an accurate diagnosis.[8]

Terminology

Depending on appearance, symptoms, aetiological assumptions and histopathological findings a variety of terms has been used to describe mastitis and various related aspects.

- Galactopoiesis: milk production

- Secretory disease: aberrant secretory activity in the lobular and lactiferous duct system, believed to be the most frequent factor causing galactophoritis. The secretions may be milk like or apocrine luminal fluid.

- Retention syndrome (aka retention mastitis): accumulation of secretions in the ducts with mainly intraductal inflammation.

- Galactostasis: like retention syndrome where the secret is known to be milk.

- Galactophoritis: inflammation of the lobular and lactiferous duct system, mainly resulting from secretory disease and retention syndrome.

- Plasma cell mastitis: plasma cells from the intraductal inflammation infiltrate surrounding tissue.

- Duct ectasia: literally widening of lactiferous ducts - relatively common finding in breast exams, increase with age. Strongly correlated with cyclic and very strongly with noncyclic breast pain. Correlation with mastitis is of anecdotal quality and has been questioned by recent research.

- Duct ectasia syndrome: in older literature this was used as synonym for nonpuerperal mastitis with recurring breast abscess, nipple discharge and possibly associated fibrocystic condition with blue dome cysts. Recent research shows that duct ectasia is only very weakly correlated with mastitis symptomes (inflammation, breast abscess). The use of the terms Duct Ectasia and Duct Ectasia Syndrome is inconsistent throughout the literature.

- Squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts: cuboid cells in the epithelial lining of the lactiferous ducts transform (squamous metaplasia) to squamous epithelial cells. Present in many cases of subareolar abscesses.

- Subareolar abscess: abscess bellow or in close vicinity of the areola. Mostly resulting from galactophoritis.

- Retroareolar abscess: deeper (closer to chest) than the lobular ductal system and thus deeper than a subareolar abscess.

- Periductal inflammation (aka periductal mastitis): inflammation infiltrated tissue surrounding lactiferous ducts. Almost synonym for subaerolar abscess. May be just a different name for plasma cell mastitis.

- Fistula: fine channel draining an abscess cavity

- Zuska's disease: periareolar abscess associated with squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts. Some authors also associate this with nipple discharge.

References

- ↑ Amir LH, Garland SM, Lumley J. (2006). "A case-control study of mastitis: nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus". BMC Family Practice. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-7-57.

- ↑ Amir LH, Garland SM, Lumley J. (2006). "A case-control study of mastitis: nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus". BMC Family Practice. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-7-57.

- ↑ Amir LH, Garland SM, Lumley J. (2006). "A case-control study of mastitis: nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus". BMC Family Practice. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-7-57.

- ↑ Peters F, Schuth W (1989). "Hyperprolactinemia and nonpuerperal mastitis (duct ectasia)". JAMA. 261 (11): 1618–20. PMID 2918655.

- ↑ Kutsuna S, Mezaki K, Nagamatsu M, Kunimatsu J, Yamamoto K, Fujiya Y; et al. (2015). "Two Cases of Granulomatous Mastitis Caused by Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii Infection in Nulliparous Young Women with Hyperprolactinemia". Intern Med. 54 (14): 1815–8. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4254. PMID 26179543.

- ↑ Risager R, Bentzon N (2010). "[Smoking and increased risk of mastitis]". Ugeskr Laeger. 172 (33): 2218–21. PMID 20727287.

- ↑ Ocal K, Dag A, Turkmenoglu O, Kara T, Seyit H, Konca K (2010). "Granulomatous mastitis: clinical, pathological features, and management". Breast J. 16 (2): 176–82. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00879.x. PMID 20030652.

- ↑ Summers TA, Lehman MB, Barner R, Royer MC (2009). "Lupus mastitis: a clinicopathologic review and addition of a case". Adv Anat Pathol. 16 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181915ff7. PMID 19098467.