Loeffler endocarditis: Difference between revisions

| Line 308: | Line 308: | ||

===Secondary Prevention=== | ===Secondary Prevention=== | ||

* Effective measures for the secondary prevention of Loeffler endocarditis include having clinical impression about the disease and hence early diagnosis, application of multimodality imaging, early treatment of both complications and the underling disease and appropriate follow ups for relapses and complications.<ref name="pmid25300524" /> | |||

Effective measures for the secondary prevention of Loeffler endocarditis include | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 16:03, 21 June 2019

| Loeffler endocarditis | |

| |

|---|---|

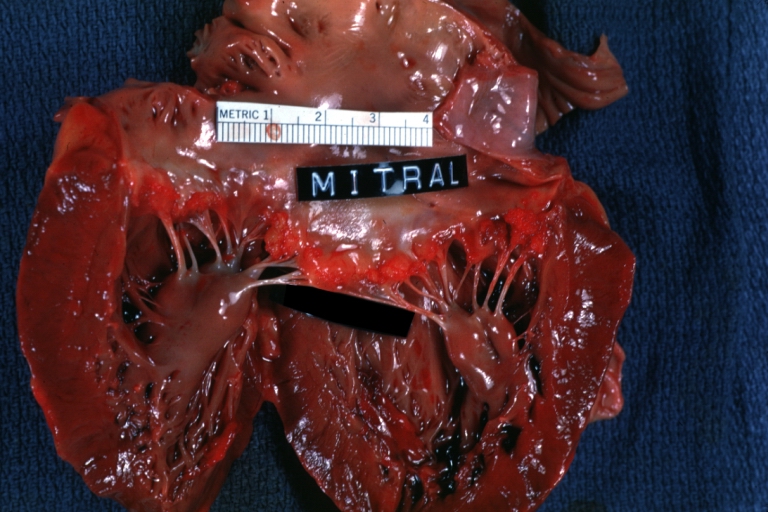

| HEART: An excellent example of Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis. Gross: Mitral valve Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | I42.3 |

| ICD-9 | 421.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 4291 |

| eMedicine | med/1318 |

Template:Search infobox Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Soroush Seifirad, M.D.[2]

Loeffler endocarditis, a form of endocarditis, is one of the two forms of hypereosinophilic syndrome. It is a restricive cardiomyopathy characterized eosinophilia and eosinophilic penetration leading to the fibrotic thickening of portions of the heart (similar to that of endomyocardial fibrosis) and commonly has large mural thrombi. Commonly found in temperate climates.

Common symptoms include edema and breathlessness.

It is named for Wilhelm Löffler.[1][2]

++++++

My references:

general [3]

adalimumab [11]

3d echo: [12]

Churg-Strauss [13]

Multiparametric cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) [14]

imatinib treatment [15]

Overview

Historical Perspective

- Loeffler endocarditis was first discovered by , Wilhelm Loeffler, a Swiss clinician scientist, in 1936.

REF: Loffler W: Endocarditis parietalis fibroplastica mit Blut-eosinophilie, ein eigenartiges Krankheitsbild. Schweiz Med Wochenschr; 1936 66: 817-820.

Classification

- Loeffler endocarditis is now regarded as a manifestation of eosinophilic myocarditis, a disorder that involves the infiltration of heart tissue by blood-born eosinophils that leads to three progressive clinical stages.

- The first or inflammatory stage involves acute inflammation and subsequent necrosis.

- This stage is dominated by signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome such as angina, heart attack, and congestive heart failure.

- In the second stage, the endocardium (i.e. interior wall) of the heart forms blood clots which break off and then travel through and block various arteries; this thrombotic stage may dominate the initial presentation in some individuals.

- The third stage is a fibrotic stage, i.e. Loeffler endocarditis, wherein scarring replaces damaged heart muscle tissue to cause a poorly contracting heart and/or cardiac valve disease. Recent publications commonly refer to Loeffler endocarditis as a historical term for the third stage of eosinophilic myocarditis. The exact pathogenesis of Loeffler endocarditis is not fully understood.

Pathophysiology

- The disorder develops because of eosinophilic penetration into the cardiac tissues.

- This leads to a fibrotic thickening of portions of the heart (similar to that of endomyocardial fibrosis) and heart valves.

- In consequence, the heart becomes rigid and poorly contractile while the heart valves may become stenotic or insufficient, i.e. reduced in ability to open or close, respectively.

- The damaged heart may also develop mural thrombi, i.e. clots which lay against ventricle walls, tend to break off, and flow through and block arteries; this condition often precedes the fibrotic stage of eosinophilic myocarditis and is termed the thrombotic stage.

- Eosinophilic states that may occur in and underlie Loeffler endocarditis (as well as the other stages of eosinophilic myocarditis) include primary and secondary eosinophilias or hypereosinophilias.

- Primary eosinophilias or hypereosinophilias (i.e. disorders in which the eosinophil appears to be intrinsically diseased) that lead to Loeffler endocarditis are clonal hypereosinophilia, chronic eosinophilic leukemia and the hypereosinophilic syndrome.

- Secondary causes (i.e. disorders in which other diseases cause the eosinophil to become dysfunctional) include:

- Allergic and autoimmune diseases;

- Infections due to certain parasitic worms, protozoa, and viruses;

- Malignant and premalignant hematologic disorders commonly associated with eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia;

- Adverse reactions to various drugs.

Causes

- The cause of Loeffler endocarditis has not been identified in most of the cases.

- Nevertheless, Loeffler endocarditis may be caused by hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic leukaemia, carcinoma, lymphoma, drug reactions, parasites.

Differentiating Loeffler endocarditis from Other Diseases

- Loeffler endocarditis must be differentiated from Other causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis and myeloma.

- In children, Loeffler endocarditis might be associated with rhabdomyosarcoma or tuberose sclerosis.

Epidemiology and Demographics

The incidence/prevalence of Loeffler endocarditis is approximately [number range] per 100,000 individuals worldwide.

OR

In [year], the incidence/prevalence of Loeffler endocarditis was estimated to be [number range] cases per 100,000 individuals worldwide.

OR

In [year], the incidence of Loeffler endocarditis is approximately [number range] per 100,000 individuals with a case-fatality rate of [number range]%.

Patients of all age groups may develop Loeffler endocarditis .

OR

The incidence of Loeffler endocarditis increases with age; the median age at diagnosis is [#] years.

OR

Loeffler endocarditis commonly affects individuals younger than/older than [number of years] years of age.

OR

[Chronic disease name] is usually first diagnosed among [age group].

OR

[Acute disease name] commonly affects [age group].

There is no racial predilection to Loeffler endocarditis .

OR

Loeffler endocarditis usually affects individuals of the [race 1] race. [Race 2] individuals are less likely to develop Loeffler endocarditis .

Loeffler endocarditis affects men and women equally.

OR

[Gender 1] are more commonly affected by Loeffler endocarditis than [gender 2]. The [gender 1] to [gender 2] ratio is approximately [number > 1] to 1.

The majority of Loeffler endocarditis cases are reported in [geographical region].

OR

Loeffler endocarditis is a common/rare disease that tends to affect [patient population 1] and [patient population 2].

Risk Factors

- There are no established risk factors for Loeffler endocarditis .

OR

The most potent risk factor in the development of Loeffler endocarditis is [risk factor 1]. Other risk factors include [risk factor 2], [risk factor 3], and [risk factor 4].

OR

Common risk factors in the development of Loeffler endocarditis include [risk factor 1], [risk factor 2], [risk factor 3], and [risk factor 4].

OR

Common risk factors in the development of Loeffler endocarditis may be occupational, environmental, genetic, and viral.

Screening

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for Loeffler endocarditis.

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

- The signs and symptoms of Loeffler endocarditis tend to reflect the many underlying disorders causing eosinophil dysfunction as well as the widely differing progression rates of cardiac damage.

- Before cardiac symptoms are detected, individuals may suffer symptoms of a common cold, asthma, rhinitis, urticarial, or other allergic disorder.

- Cardiac manifestations include life-threatening conditions such as cardiogenic shock or sudden death due to abnormal heart rhythms.

- More commonly, however, the presenting cardiac signs and symptoms of the disorder are the same as those seen in other forms of cardiomyopathy: the heart arrhythmia of ventricular fibrillation seen as an irregular pulse and heart rate, other cardiac arrhythmias, symptoms of these arrhythmias such as chest palpitations, dizziness, light headedness, and fainting; and symptoms of a heart failure such as fatigue, edema, i.e. swelling, of the lower extremities, and shortness of breath.

- Early cardiac involvement occurs in 20 to 50% of cases. Systemic emboli may cause renal or neurological problems.

- The third stage is a fibrotic stage, i.e. Loeffler endocarditis, wherein scarring replaces damaged heart muscle tissue to cause a poorly contracting heart and/or cardiac valve disease. Recent publications commonly refer to Loeffler endocarditis as a historical term for the third stage of eosinophilic myocarditis. The exact pathogenesis of Loeffler endocarditis is not fully understood.

- Prognosis is generally poor but depends upon the degree of involvement of the heart.

- The mean survival time of patients with Loeffler endocarditis is approximately 18 months

- If left untreated, [#]% of patients with Loeffler endocarditis may progress to develop [manifestation 1], [manifestation 2], and [manifestation 3]. OR Common complications of Loeffler endocarditis include [complication 1], [complication 2], and [complication 3]. OR

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis should be considered in individuals exhibiting signs and symptoms of poor heart contractility and/or valve disease in the presence of significant increases in blood eosinophil counts.

- Ancillary tests may help in the diagnosis.

- However, the only definitive test for Loeffler endocarditis is cardiac muscle biopsy showing the presence of eosinophilic infiltrates.

Diagnostic Study of Choice

- The definite diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis is based on cardiac muscle biopsy, showing the presence of eosinophilic infiltrates and sometimes fibrosis.

- Since the disorder may be patchy, multiple tissue samples taken during the procedure improve the chances of uncovering the pathology but in any case negative results do not exclude the diagnosis.

History and Symptoms

- The most common symptoms of Loeffler endocarditis include weight loss, fever, cough, a rash (possibly pruritic) and symptoms of congestive heart failure.

Physical Examination

- Common physical examination findings of Loeffler endocarditis include peripheral oedema, elevated jugular venous pressure, tachycardia, murmur of mitral regurgitation, S3 gallop and possibly S4 sound. (physical findings of heart failure)

- Palpable apex beat and mitral regurgitation help to differentiate restrictive cardiomyopathy may be very similar to those of constrictive pericarditis.

Laboratory Findings

- Hypereosinophilia (i.e. blood eosinophil counts at or above 1,500 per microliter) or, less commonly, eosinophilia (counts above 500 but below 1,500 per microliter) are found in the vast majority of cases and are valuable clues pointing to this rather than other types of cardiomyopathies.

- However, elevated blood eosinophil counts may not occur during the early phase of the disorder.

- Other, less specific laboratory findings implicate a cardiac disorder but not necessarily eosinophilic myocarditis.

- These include elevations in blood markers for systemic inflammation (e.g. C reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and cardiac injury (e.g. creatine kinase, troponins);

- Laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis include marked eosinophilia - at least 0.44 x 109/l.

Electrocardiogram

- An ECG may be helpful in the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis. Findings on an ECG suggestive of/diagnostic of Loeffler endocarditis include ST segment-T wave abnormalities.

X-ray

- An x-ray may be helpful in the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis.

- Findings on an x-ray suggestive of Loeffler endocarditis include cardiomegaly and presentation of heart failure and pulmonary edema.

- Nevertheless, these findings are neither specific nor sensitive for the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis.

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

- Echocardiography may be helpful in the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis.

- Findings on an echocardiography suggestive of/diagnostic of Loeffler endocarditis include restrictive filling but pretty good left ventricular systolic function.

- Echocardiography typically gives non-specific and only occasional findings of endocardium thickening, left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricle dilation, and involvement of the mitral and/or tricuspid valves.

CT scan

- Although multimodality imaging is recommended in diagnosis and management of Loeffler endocarditis, but CT scan is barely used a an imaging modality.[16]

- MRI and Ecocardiography were used extensively in diagnosis and management of these cases.

MRI

- Cardiac MRI may be helpful in the diagnosis of Loeffler endocarditis.

- Gadolinium-based cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is the most useful non-invasive procedure for diagnosing eosinophilic myocarditis.

- Findings on MRI suggestive of/diagnostic of Loeffler endocarditis include at least two of the following abnormalities:

- An increased signal in T2-weighted images;

- An increased global myocardial early enhancement ratio between a myocardial and skeletal muscle in enhanced T1 images and

- One or more focal enhancements distributed in a non-vascular pattern in late enhanced T1-weighted images.

- Additionally, and unlike in other forms of myocarditis, eosinophilic myocarditis may also show enhanced gadolinium uptake in the sub-endocardium.

Other Imaging Findings

- There are no other imaging findings associated with Loeffler endocarditis.

Other Diagnostic Studies

- There are no other diagnostic studies associated with Loeffler endocarditis.

Treatment

- Small studies and case reports have directed efforts towards:

- supporting cardiac function by relieving heart failure and suppressing life-threatening abnormal heart rhythms;

- suppressing eosinophil-based cardiac inflammation; and

- treating the underlying disorder.

- In all cases of Loeffler endocarditis that have no specific treatment regimens for the underlying disorder, available studies recommend treating the inflammatory component of this disorder with non-specific immunosuppressive drugs, principally high-dosage followed by slowly-tapering to low-dosage maintenance corticosteroid regimens. Afflicted individuals who fail this regimen or present with cardiogenic shock may benefit from treatment with other non-specific immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine or cyclophosphamide, as adjuncts to, or replacements for, corticosteroids. However, individuals with an underlying therapeutically accessible disease should be treated for this disease; in seriously symptomatic cases, such individuals may be treated concurrently with a corticosteroid regimen. Examples of diseases underlying Loeffler's myocarditis that are recommended for treatments directed at the underlying disease include:

- Infectious agents: specific drug treatment of helminth and protozoan infections typically take precedence over non-specific immunosuppressive therapy, which, if used without specific treatment, could worsen the infection. In moderate-to-severe cases, non-specific immunosuppression is used in combination with specific drug treatment.

- Toxic reactions to ingested agents: discontinuance of the ingested agent plus corticosteroids or other non-specific immunosuppressive regimens.

- Clonal eosinophilia caused by mutations in genes that are highly susceptible to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or possibly FGFR1: first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. imatinib) are recommended for the former two mutations; a later generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, ponatinib, alone or combined with bone marrow transplantation, may be useful for treating the FGFR1 mutations.

- Clonal hypereosinophilia due to mutations in other genes or primary malignancies: specific treatment regimens used for these pre-malignant or malignant diseases may be more useful and necessary than non-specific immunosuppression.

- Allergic and autoimmune diseases: non-specific treatment regimens used for these diseases may be useful in place of a simple corticosteroid regimen. For example, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis can be successfully treated with mepolizumab.

- Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome and lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia: corticosteroids; for individuals with these hypereosinophilias that are refractory to or breakthrough corticosteroid therapy and individuals requiring corticosteroid-sparing therapy, recommended alternative drug therapies include hydroxyurea, Pegylated interferon-α, and either one of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib and mepolizumab).

Medical Therapy

- The mainstay of treatment for Loeffler endocarditis is congestive heart failure treatment.

- Diuretics

- Digoxin

- ACE inhibitors

- Drugs that reduce afterload.

- Immune suppression and cytotoxic drugs are recommended in the early disease phase of the patients who develop Loeffler endocarditis.

- Patients with acute myocarditis are treated with steroids, whereas prednisolone and hydroxycarbamide could be helpful to suppress eosinophilia in the patients.

- Once fibrosis has occurred, surgery may be of benefit. (See below)

Surgery

- The mainstay of treatment for Loeffler endocarditis is medical therapy. Surgery is usually reserved for patients with fibrosis.

- Removing fibrosed endocardium might be helpful to improve elasticity.

- Mitral and even tricuspid valves might be indicated in some patients.

- common complication is complete heart block.

- Operative mortality is 15-30%

Primary Prevention

- There are no established measures for the primary prevention of Loeffler endocarditis.

Secondary Prevention

- Effective measures for the secondary prevention of Loeffler endocarditis include having clinical impression about the disease and hence early diagnosis, application of multimodality imaging, early treatment of both complications and the underling disease and appropriate follow ups for relapses and complications.[16]

References

- ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ W. Löffler. Endocarditis parietalis fibroplastica mit Bluteosinophilie. Ein eigenartiges Krankheitsbild. Schweizerische medizinische Wochenschrift, Basel, 1936, 66: 817-820.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Alam A, Thampi S, Saba SG, Jermyn R (2017) Loeffler Endocarditis: A Unique Presentation of Right-Sided Heart Failure Due to Eosinophil-Induced Endomyocardial Fibrosis. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 10 ():1179547617723643. DOI:10.1177/1179547617723643 PMID: 28890659

- ↑ Benezet-Mazuecos J, de la Fuente A, Marcos-Alberca P, Farre J (2007) Loeffler endocarditis: what have we learned? Am J Hematol 82 (10):861-2. DOI:10.1002/ajh.20957 PMID: 17573694

- ↑ Gao M, Zhang W, Zhao W, Qin L, Pei F, Zheng Y (2018) Loeffler endocarditis as a rare cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 97 (11):e0079. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000010079 PMID: 29538200

- ↑ Kalra DK, Park J, Hemu M, Goldberg A (2019) Loeffler Endocarditis: A Diagnosis Made with Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Cardiovasc Imaging 27 (1):70-72. DOI:10.4250/jcvi.2019.27.e5 PMID: 30701721

- ↑ Chao BH, Cline-Parhamovich K, Grizzard JD, Smith TJ (2007) Fatal Loeffler's endocarditis due to hypereosinophilic syndrome. Am J Hematol 82 (10):920-3. DOI:10.1002/ajh.20933 PMID: 17534930

- ↑ Sen T, Ponde CK, Udwadia ZF (2008) Hypereosinophilic syndrome with isolated Loeffler's endocarditis: complete resolution with corticosteroids. J Postgrad Med 54 (2):135-7. PMID: 18480530

- ↑ Osovska NY, Kuzminova NV, Knyazkova II (2016) Loeffler endocarditis in young woman - a case report. Pol Merkur Lekarski 41 (245):231-237. PMID: 27883350

- ↑ Niemeijer ND, van Daele PL, Caliskan K, Oei FB, Loosveld OJ, van der Meer NJ (2012) Löffler endocarditis: a rare cause of acute cardiac failure. J Cardiothorac Surg 7 ():109. DOI:10.1186/1749-8090-7-109 PMID: 23046536

- ↑ Hussain N, Patel P, Yin J, Davis R, Ikladios O (2019) A case of Loeffler's endocarditis after initiation of adalimumab. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 9 (1):29-32. DOI:10.1080/20009666.2018.1562852 PMID: 30788072

- ↑ Hernandez CM, Arisha MJ, Ahmad A, Oates E, Nanda NC, Nanda A et al. (2017) Usefulness of three-dimensional echocardiography in the assessment of valvular involvement in Loeffler endocarditis. Echocardiography 34 (7):1050-1056. DOI:10.1111/echo.13575 PMID: 28600838

- ↑ Seo JS, Song JM, Kim DH, Kang DH, Song JK (2010) A Case of Loeffler's Endocarditis Associated with Churg-Strauss Syndrome. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 18 (1):21-4. DOI:10.4250/jcu.2010.18.1.21 PMID: 20661332

- ↑ Gastl M, Behm P, Jacoby C, Kelm M, Bönner F (2017) Multiparametric cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) for the diagnosis of Loeffler's endocarditis: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17 (1):74. DOI:10.1186/s12872-017-0492-7 PMID: 28284183

- ↑ Rotoli B, Catalano L, Galderisi M, Luciano L, Pollio G, Guerriero A et al. (2004) Rapid reversion of Loeffler's endocarditis by imatinib in early stage clonal hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 45 (12):2503-7. DOI:10.1080/10428190400002293 PMID: 15621768

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Simonnet B, Jacquier A, Salaun E, Hubert S, Habib G (2015) Cardiac involvement in hypereosinophilic syndrome: role of multimodality imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16 (2):228. DOI:10.1093/ehjci/jeu196 PMID: 25300524