Gingivitis

| Gingivitis | |

| |

|---|---|

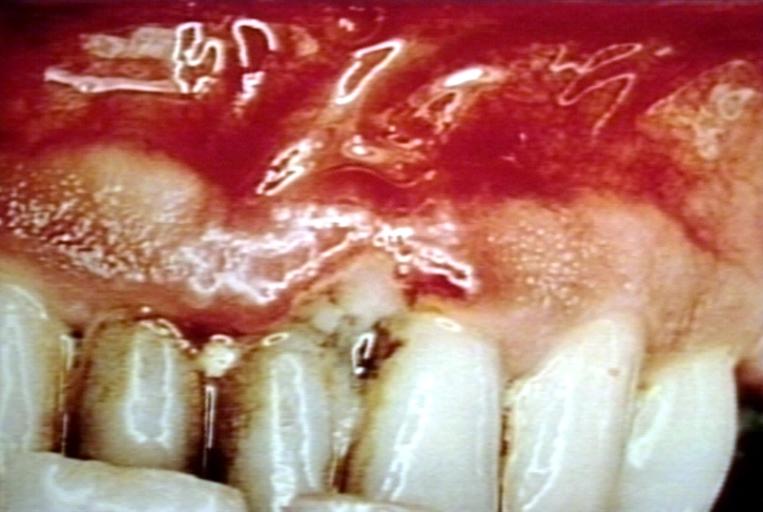

| Trench mouth. Necrotizing gingivitis Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | K05.0-K05.1 |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Gingivitis |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Gingivitis |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Gingivitis at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Gingivitis at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Gingivitis

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Gingivitis Discussion groups on Gingivitis Patient Handouts on Gingivitis Directions to Hospitals Treating Gingivitis Risk calculators and risk factors for Gingivitis

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Gingivitis |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ogheneochuko Ajari, MB.BS, MS [2] Jaspinder Kaur, MBBS[3]

Synonyms and keywords:

Overview

Gingivitis ("inflammation of the gums") (gingiva) around the teeth is a general term for gingival diseases affecting the gingiva (gums)[1]. As generally used, the term gingivitis refers to gingival inflammation induced by bacterial biofilms (also called plaque) adherent to tooth surfaces.

Classification

Pathophysiology

Gingivitis is usually caused by bacterial plaque that accumulates in the spaces between the gums and the teeth and in calculus (tartar) that forms on the teeth. These accumulations may be tiny, even microscopic, but the bacteria in them produce foreign chemicals and toxins that cause inflammation of the gums around the teeth. This inflammation can, over the years, cause deep pockets between the teeth and gums and loss of bone around teeth otherwise known as periodontitis.

Since the bone in the jaws holds the teeth into the jaws, the loss of bone can cause teeth over the years to become loose and eventually to fall out or need to be extracted because of acute infection. Regular cleanings (correctly termed periodontal debridement, scaling or root planing) below the gum line, best accomplished professionally by a dental hygienist or dentist, disrupt this plaque biofilm and remove plaque retentive calculus (tartar) to help prevent inflammation. Once cleaned, plaque will begin to grow on the teeth within hours. However, it takes approximately 3 months for the pathogenic type of bacteria (typically gram negative anaerobes and spirochetes) to grow back into the deep pockets and restart the inflammatory process. Calculus (tartar) may start to reform within 24 hours. Ideally, scientific studies show that all people with deep periodontal pockets (greater than 5mm) should have the pockets between their teeth and gums cleaned by a dental hygienist or dentist every 3-4 months.

People with a healthy periodontium (gums, bone and ligament) or people with gingivitis only require periodontal debridement every 6 months. However, many dental professionals only recommend periodontal debridement (cleanings) every 6 months, because this has been the standard advice for decades, and because the benefits of regular periodontal debridement (cleanings) are too subtle for many patients to notice without regular education from the dental hygienist or dentist. If the inflammation in the gums becomes especially well-developed, it can invade the gums and allow tiny amounts of bacteria and bacterial toxins to enter the bloodstream. The patient may not be able to notice this, but studies suggest this can result in a generalized increase in inflammation in the body cause possible long term heart problems. Periodontitis has also been linked to diabetes, arteriosclerosis, osteoporosis, pancreatic cancer and pre-term low birth weight babies.

Sometimes, the inflammation of the gingiva can suddenly amplify, such as to cause a disease called Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingitivitis (ANUG), otherwise known as "trench mouth." The aetiology of ANUG is the overgrowth of a particular type of pathogenic bacteria (fusiform-spirochete variety) but risk factors such as stress, poor nutrition and a compromised immune system can exacerbate the infection. This results in the breath being extremely bad-smelling, and the gums feeling considerable pain and degeration of the periodontium rapidly occurs. Fortunately, this can be cured with a 1-week course of Metronidazole antibiotic, followed by a deep cleaning of the gums by a dental hygienist or dentist and reduction of risk factors such as stress.

When the teeth are not cleaned properly by regular brushing and flossing, bacterial plaque accumulates, and becomes mineralized by calcium and other minerals in the saliva transforming it into a hard material called calculus (tartar) which harbors bacteria and irritates the gingiva (gums). Also, as the bacterial plaque biofilm becomes thicker this creates an anoxygenic environment which allows more pathogenic bacteria to flourish and release toxins and cause gingival inflammation. Alternatively, excessive injury to the gums caused by very vigorous brushing may lead to recession, inflammation and infection. Pregnancy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and the onset of puberty increase the risk of gingivitis, due to hormonal changes that may increase the susceptibility of the gums or alter the composition of the dentogingival microflora. The risk of gingivitis is increased by misaligned teeth, the rough edges of fillings, and ill fitting or unclean dentures, bridges, and crowns. This is due to their plaque retentive properties. The drug phenytoin, birth control pills, and ingestion of heavy metals such as lead and bismuth may also cause gingivitis.

The sudden onset of gingivitis in a normal, healthy person should be considered an alert to the possibility of an underlying viral aetiology, although most systemically healthy individuals have gingivitis in some area of their mouth, usually due to inadequate brushing and flossing.

Causes

Life Threatening Causes

Life-threatening causes include conditions which may result in death or permanent disability within 24 hours if left untreated.

Common Causes

Causes by Organ System

Causes in Alphabetical Order

| A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | G | H | I | K |

| L | M | N | O | P |

| R | S | T | V | Z |

Differentiating Gingivitis from other Diseases

| Differentiating condition | Differentiating sign and symptoms | Differentiating features |

|---|---|---|

| Oral lichen planus |

|

|

| Pemphigoid |

|

|

| Pemphigus |

|

|

| Lupus erythematosus |

|

|

| Desquamative gingivitis |

|

|

| Drug-influenced gingival enlargement |

|

|

| Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis |

|

|

| Allergic reactions |

|

|

| Leukemia |

|

|

| Gingival candidosis |

|

|

| Primary and metastatic carcinoma | *Most gingival carcinomas, both primary and metastatic, present with localized exophytic masses rather than diffuse pseudoinflammatory changes generally associated with gingivitis. |

|

| Foreign body gingivitis |

|

|

| Orofacial granulomatosis |

|

|

| Pyostomatitis vegetans |

| |

| Linear IgA disease |

|

|

| Wegener granulomatosis |

|

|

| Erythema multiforme |

|

|

| Agranulocytosis |

|

|

| Histoplasmosis |

|

|

| Cyclic neutropenia |

|

|

| Differential diagnosis |

|---|

|

Epidemiology and Demographics

Risk Factors

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- Recurrence of gingivitis

- Periodontitis

- Infection or abscess of the gingiva or the jaw bones

- Trench mouth (bacterial infection and ulceration of the gums)

Clinical presentation

Symptoms

The symptoms of gingivitis are as follows:

- Swollen gums

- Mouth sores

- Bright-red, or purple gums

- Shiny gums

- Gums that are painless, except when pressure is applied

- Gums that bleed easily, even with gentle brushing,and especially when you floss

- Gums that itch with varying degrees of severity

- Receding gumline

Diagnosis

It is recommended that a dental hygienist or dentist be seen after the signs of gingivitis appear. A dental hygienist or dentist will check for the symptoms of gingivitis, and may also examine the amount of plaque in the oral cavity. A dental hygienist or dentist should also test for periodontitis using X-rays or gingival probing as well as other methods.

Treatment

A dentist or dental hygienist will perform a thorough cleaning of the teeth and gums; following this, persistent oral hygiene is necessary. The removal of plaque is usually not painful, and the inflammation of the gums should be gone between one and two weeks. A gargling of Brine Water also helps. Oral hygiene including proper brushing and flossing is required to prevent the recurrence of gingivitis. Anti-bacterial rinses or mouthwash, in particular Chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2% solution, may reduce the swelling and local mouth gels which are usually antiseptic and anaesthetic can also help.

Prevention

Gingivitis can be prevented through regular oral hygiene that includes daily brushing and flossing.

Researchers analyzed government data on calcium consumption and periodontal disease indicators in nearly 13,000 people representing U.S. adults. They found that men and women who had calcium intakes of fewer than 500 milligrams, or about half the recommended dietary allowance, were almost twice as likely to have gum disease, as measured by the loss of attachment of the gums from the teeth. The association was particularly evident for people in their 20s and 30s.

Research says the relationship between calcium and gum disease is likely due to calcium’s role in building density in the alveolar bone that supports the teeth.

References

- ↑ The American Academy of Periodontology. Proceedings of the World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics. Chicago:The American Academy of Periodontology; 1989:I/23-I/24.

External links

- Gingivitis - Medline plus

Template:Periodontology

Template:Oral pathology

zh-min-nan:Khí-hoāⁿ-iām

de:Gingivitis

el:Ουλίτιδα

it:Gengivite

nl:Tandvleesontsteking

simple:Gingivitis

fi:Ientulehdus

sv:Gingivit