Extramammary Paget's disease pathophysiology

|

Extramammary Paget's disease Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Extramammary Paget's disease from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Extramammary Paget's disease pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Extramammary Paget's disease pathophysiology |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Extramammary Paget's disease |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Extramammary Paget's disease pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Simrat Sarai, M.D. [2]

Overview

On gross pathology, a plaque with an irregular border and erythematous or white skin lesion are characteristic findings of extramammary Paget's disease. On microscopic histopathological analysis, Paget's cells (large cells with abundant amphophilic or basophilic, finely granular cytoplasm, large centrally-located nucleus with prominent nucleolus) and signet ring cells are characteristic findings of extramammary Paget's disease. Extramammary Paget's disease arises from keratinocytic stem cells or from apocrine gland ducts. Approximately 25% (range 9-32%) of the cases of extramammary Paget's disease are associated with an underlying in situ or invasive neoplasm. The neoplasm most likely to be associated with extramammary Paget's disease is an adnexal apocrine carcinoma, which usually represents infiltration of the deeper adnexa by epidermal Paget's cells.[1][2]

Pathophysiology

Gross Pathology

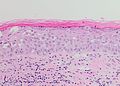

On gross pathology, the following are characteristic findings of extramammary Paget's disease:[2]

- Plaque with an irregular border

- Erythematous or white lesion

- Eczematous appearance

- May have a ring-shaped appearance

Microscopic Pathology

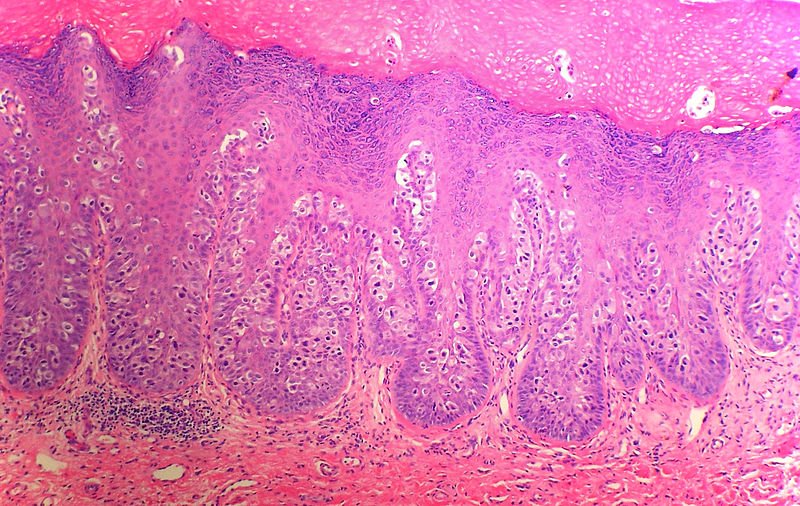

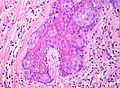

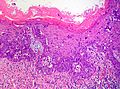

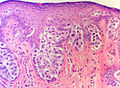

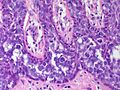

- Paget's cells are large cells with abundant amphophilic or basophilic, finely granular cytoplasm, which tend to stand out in contrast to the surrounding epithelial cells.

- The nucleus is usually large, centrally situated, and sometimes contains a prominent nucleolus. Prominent nuclear atypia and pleomorphism are present.

- Signet ring cells may be present in small numbers and mitotic figures are more frequent.

- The Paget's cells may be dispersed singly or form clusters, solid nests, or glandular structures. The majority of cells are concentrated in the lower strata, but there may be infiltration into upper strata of the epidermis, often being observed in the pilosebaceous apparatus.

- Cells may be present in sweat gland ducts, leading to confusion as to whether the lesion has spread from a local apocrine neoplasm or has arisen within the epidermis. A dense inflammatory infiltrate is often seen associated with the epidermal malignancy.

- In approximately more than 90% of cases of extramammary Paget's disease the tumor cells contain cytoplasmic mucin, stain positively with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and mucicarmine reagent. Only 40% of cases of mammary Paget's disease show any intracellular mucin and staining is generally weaker than in extramammary Paget's disease.

- Cytological examination of skin scrapings from lesions of Paget's disease reveals eccentric nuclei and single malignant cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, three dimensional cell aggregates, and acinar groups consistent with glandular differentiation. However, the material obtained is variably cellular and often shows a background of keratinous debris, which may lead to confusion with squamous neoplasia or inflammatory skin conditions or squamous neoplasia. Hence, it may be more appropriate to biopsy lesions.[3]

-

Anus Pagets Disease - Notice that the neoplastic cells ride above the normal basal cells (SKB)

-

Anus Pagets Disease

-

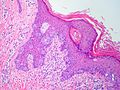

Penis Paget Disease - medium power - (SKB)

-

Vulva Paget Disease - low power - (SKB)

-

Vulva Paget Disease - medium power - (SKB)

-

Vulva Paget Disease - medium power - (SKB)

-

Anus Pagets Disease - (SKB)

-

Penis Paget Disease - high power - (SKB)

Pathogenesis

- In majority of cases extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) arises as a primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma. The epidermis becomes infiltrated with neoplastic cells showing glandular differentiation. Tumor cells may originate from keratinocytic stem cells or from apocrine gland ducts. The cause of primary extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) is unknown. However, a minority of cases do represent a direct extension of an underlying carcinoma along contiguous epithelium.

- Approximately 25% (range, 9-32%) of the cases of EMPD are associated with an underlying in situ or invasive neoplasm. The neoplasm most likely to be associated with EMPD is an adnexal apocrine carcinoma. This associated neoplasm probably represents infiltration of the deeper adnexa by epidermal Paget cells. Other malignancies besides cutaneous adnexal carcinoma that may be associated with EMPD include carcinomas of the urethra, Bartholin's glands, vagina, bladder, cervix, endometrium, and prostate

- The anatomic location of extramammary Pagets's disease (EMPD) plays a role in predicting the risk of associated carcinoma. For example, genital disease is associated with carcinoma in about approximately 4-7% of patients. Perianal disease is associated with underlying colorectal carcinoma in approximately 25-35% of cases.[1]

- Rare cases of EMPD which are associated with tumors arising in distant organs without direct epithelial connection to the affected epidermis have been reported.

Immunohistochemistry

- Immunohistochemistry has been used both to identify the likely cell of origin and to diagnose Paget's disease.[4] [5]

- Paget's cells typically stain for markers of eccrine and apocrine derivation including gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15), low molecular weight cytokeratins (CK), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Staining for S100 is negative.[6][7][8]

- There are antigenic differences between primary intraepidermal Paget's disease (CK7 positive, CK20 negative, GCDFP-15 positive) and Paget's disease that has spread from an associated internal carcinoma (CK7 negative, CK20 positive, GCDFP-15 negative).

- The main histological diagnoses to exclude in the vulva are anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia (S100 negative, PAS negative) and superficial spreading malignant melanoma (S100 positive, PAS negative, CEA negative, cytokeratin negative).

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. 34BE12 the benign keratinocytes are positive (SKB)

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. CEA (SKB)

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. CK7 (SKB)

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. CK20 (SKB)

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. GATA3 (SKB

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. (SKB)

-

Vulva - Primary cutaneous extramammary Paget disease. p63 - the benign keratinocytes are positive (SKB)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roy J, Mirnezami A, Gatt M, Sasapu KK, Scott N, Sagar PM (2010). "A rare case of Paget's disease in a retrorectal dermoid cyst". Colorectal Dis. 12 (9): 946–7. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02102.x. PMID 19888952.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ameloblastoma. Libre pathology(2015) http://librepathology.org/wiki/index.php/Extramammary_Paget_disease#Microscopic Accessed on January 30, 2016

- ↑ Lloyd, J (2000). "Mammary and extramammary Paget's disease". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 53 (10): 742–749. doi:10.1136/jcp.53.10.742. ISSN 0021-9746.

- ↑ Guarner J, Cohen C, DeRose PB (1989). "Histogenesis of extramammary and mammary Paget cells. An immunohistochemical study". Am J Dermatopathol. 11 (4): 313–8. PMID 2549798.

- ↑ Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Haagensen DE (1984). "Extramammary Paget's disease--evidence for an apocrine origin. An immunoperoxidase study of gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and keratin proteins". Am J Surg Pathol. 8 (1): 43–50. PMID 6198933.

- ↑ Lloyd J, Flanagan AM (2000). "Mammary and extramammary Paget's disease". J Clin Pathol. 53 (10): 742–9. PMC 1731095. PMID 11064666.

- ↑ Jones, R. Russell; Spaull, J.; Gusterson, B. (1989). "The histogenesis of mammary and extramammary Paget's disease". Histopathology. 14 (4): 409–416. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb02169.x. ISSN 0309-0167.

- ↑ Goldblum JR, Hart WR (1997). "Vulvar Paget's disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases". Am J Surg Pathol. 21 (10): 1178–87. PMID 9331290.