|

|

| (107 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | __NOTOC__ |

| | {| class="infobox" style="float:right;" |

| | |- |

| | | [[File:Siren.gif|30px|link=Infective endocarditis resident survival guide]]|| <br> || <br> |

| | | [[Infective endocarditis resident survival guide|'''Resident'''<br>'''Survival'''<br>'''Guide''']] |

| | |} |

| {{Infobox_Disease | | | {{Infobox_Disease | |

| Name = {{PAGENAME}} | | | Name = {{PAGENAME}} | |

| Image = 1698.jpg | | | Image = 1698.jpg | |

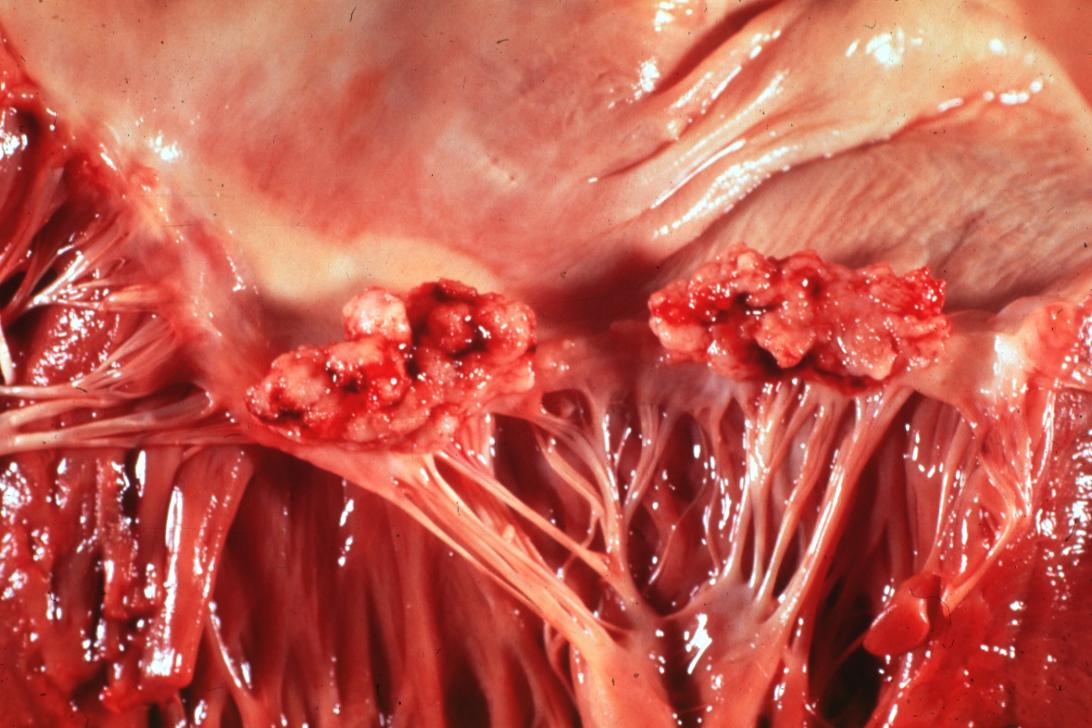

| Caption = Mitral valve vegetations in a patient with bacterial endocarditis. | | | Caption = Mitral valve vegetations in a patient with bacterial endocarditis. | |

| DiseasesDB = 4224 |

| |

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|I|33||i|30}} |

| |

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|421}} |

| |

| ICDO = |

| |

| OMIM = |

| |

| MedlinePlus = 001098 |

| |

| eMedicineSubj = emerg |

| |

| eMedicineTopic = 164 |

| |

| eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|med|671}} {{eMedicine2|ped|2511}} |

| |

| MeshID = D004696 |

| |

| }} | | }} |

| | {{endocarditis}} |

| | {{CMG}}; '''Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief:''' {{Fs}}, {{Maliha}}, {{CZ}}; [[Michael W. Tempelhof]] M.D., {{DN}} |

|

| |

|

| {{SI}} | | {{SK}} Infective Endocarditis (IE); Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE); Acute bacterial endocarditis; Fungal endocarditis; Nosocomial infective endocarditis; Intravenous drug abuse endocarditis; Intravenous drug abuse infective endocarditis; Prosthetic valve endocarditis; Endocardial infection; Native valve endocarditis; HACEK endocarditis; Bloodstream infection |

| {{WikiDoc Cardiology Network Infobox}}

| |

| {{WikiDoc Cardiology News}}

| |

| {{CMG}}

| |

| | |

| '''Associate Editor-In-Chief:''' {{CZ}}

| |

| | |

| {{MWT}}

| |

| | |

| {{Editor Join}}

| |

| | |

| '''''Related Key Words and Synonyms:''''' Infective endocarditis, IE, subacute bacterial endocarditis, acute bacterial endocarditis, fungal endocarditis, nosocomial infective endocarditis, NIE, intravenous drug abuse endocarditis, intravenous drug abuse infective endocarditis, IVDA endocarditis, IVDA IE, prosthetic valve endocarditis, PVE, pacemaker endocarditis, PM infective endocarditis, PM IE, endocardial infection, native valve endocarditis, NVE, HACEK infection, bloodstream infection, marantic endocarditis

| |

| | |

| == Overview ==

| |

| | |

| '''Endocarditis''' is an [[inflammation]] of the inner layer of the [[heart]], the [[endocardium]]. The most common structures involved are the [[heart valve]]s.

| |

| | |

| [[Endocarditis]] can be classified by etiology as either ''non-infective'' or ''infective'', depending on whether a [[microorganism]] is the source of the problem.

| |

| | |

| Traditionally, infective endocarditis has been clinically divided into ''acute'' and ''subacute'' (because the patients tend to live longer in subacute as opposed to acute) endocarditis. This classifies both the rate of progression and severity of disease. Thus subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) is often due to [[streptococci]] of low virulence and mild to moderate illness which progresses slowly over weeks and months, while acute bacterial endocarditis (ABE) is a fulminant illness over days to weeks, and is more likely due to ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'' which has much greater virulence, or disease-producing capacity.

| |

| | |

| This terminology is now discouraged. The terms ''short incubation'' (meaning less than about six weeks), and ''long incubation'' (greater than about six weeks) are preferred.

| |

| | |

| Infective endocarditis may also be classified as ''culture-positive'' or ''culture-negative''. Culture-negative endocarditis is due to micro-organisms that require a longer period of time to be identified in the laboratory. Such organisms are said to be '[[Growth medium|fastidious]]' because they have demanding growth requirements. Some pathogens responsible for culture-negative endocarditis include ''[[Aspergillus]] species'', ''[[Brucella]] species'', ''[[Coxiella burnetii]]'', ''[[Chlamydia]] species'', and [[HACEK organism|HACEK bacteria]].

| |

| | |

| Finally, the distinction between ''native-valve endocarditis'' and ''prosthetic-valve endocarditis'' is clinically important. Prosthetic-valve endocarditis constitutes 10-20% of cases of endocarditis. The greatest risk is during the first 6 months after valve surgery. [[Staphylococcus epidermidis]] is the most common cause. The infection often extends into the anulus and cardiac tissues.

| |

| | |

| Patients who inject [[narcotics]] intravenously may introduce infection which will travel to the right side of the heart. In other patients without a history of intravenous exposure, [[endocarditis]] is more frequently left-sided.

| |

| | |

| === Non-infective endocarditis ===

| |

| Non-infective or marantic endocarditis is [[rare disease|rare]]. A form of sterile [[endocarditis]] is termed [[Libman-Sacks endocarditis]]; this form occurs more often in patients with [[lupus erythematosus]] and the [[antiphospholipid syndrome]]. Non-infective endocarditis may also occur in patients with [[cancer]], particularly mucinous [[adenocarcinoma]].

| |

| | |

| === Infective endocarditis ===

| |

| Given the poor vascular supply of the heart valves, entrance of infection fighting components of the bloodstream (such as [[white blood cell]]s) are reduced. So if an organism (such as [[bacterium|bacteria]]) establishes a foothold in the valves, the bodies ability to fight the infection inside the valve structures is reduced.

| |

|

| |

|

| Normally, blood flows smoothly through these valves. If they have been damaged (for instance in [[rheumatic fever]]) the trauma of non-laminar flow can increase the risk of infection.

| | ==[[Endocarditis overview|Overview]]== |

|

| |

|

| ==Historical Background of Endocarditis== | | ==[[Endocarditis historical background|Historical Perspective]]== |

|

| |

|

| *1554: Earliest report of endocarditis in medical books

| | ==[[Endocarditis classification|Classification]]== |

| *1669: Accurately described [[tricuspid valve]] [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1646: Described unusual "outgrowths" from autopsy of patient with endocarditis; detected murmurs by placing hand on patient's chest

| |

| *1708: Described unusual structures in entrance of aorta

| |

| *1715: Described abnormality in [[aortic|aortic valve]] and [[mitral valve]]

| |

| *1749: Described valvular lesions

| |

| *1769: Linked infectious disease and [[endocarditis]]; observed association with the spleen

| |

| *1784: Accurately drew intracardiac abnormalities

| |

| *1797: Showed relationship between rheumatism and heart disease

| |

| *1799: Described inflammatory process associated with [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1806: Described unusual structures in heart as "vegetations," syphilitic virus as causative agent of [[endocarditis]], and theory of antiviral treatment of [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1809: Indicated vegetations were not "outgrowths" or "buds" but particles adhering to heart wall

| |

| *1815: Elucidated inflammatory processes associated with [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1816: Invented cylindrical stethoscope to listen to heart murmurs; dismissed link between venereal disease and [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1832: Confirmed Laennec's observations

| |

| *1835-40: Named [[endocardium]] and [[endocarditis]]; described symptoms; prescribed herbal tea and bloodletting as treatment regimen; described link between acute [[rheumatoid arthritis]] and [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1852: Described consequences of embolization of vegetations throughout body. Described cutaneous nodules (named "[[Osler's nodes]]" by Libman)

| |

| *1858-71: Examined fibrin vegetation associated with [[endocarditis]] by microscope; coined term "embolism;" discussed role of bacteria, vibrios, and micrococci in [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1861: Confirmed Virchow's theory on emboli

| |

| *1862: Described granulations or foreign elements in blood and valves, which were motile and resistant to alkalis

| |

| *1868-70: Described infected arterial blood as originating from heart; proposed scarlet fever as cause of [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1869: Established "parasites" on skin transported to heart and attached to [[endocardium]]; named "mycosis endocardii"

| |

| *1872: Detected microorganisms in vegetations of [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1878: All cases of [[endocarditis]] were infectious in origin

| |

| *1878: Combined experimental physiology and infection to produce animal model of [[endocarditis]] in rabbit; noted valve had to be damaged before bacteria grafted onto valve

| |

| *1878: Micrococci enter vessels that valves were fitted into; valves exposed to abnormal mechanical attacks over long period created favorable niche for bacterial colonization

| |

| *1879: Virchow's student; employed early animal model of [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1879: Proposed etiology of [[endocarditis]] was based on infectious model and treatment should focus on eliminating "parasitic infection"

| |

| *1880: Working with Pasteur, proposed use of routine blood cultures

| |

| *1881-86: Believed [[endocarditis]] could appear during various infections; noted translocation of respiratory pathogen from pulmonary lesion to valve through blood

| |

| *1883: Believed microorganisms were result, not cause, of endocarditis

| |

| *1884: Named disease "[[infective endocarditis]]"

| |

| *1886: Demonstrated various bacteria introduced to bloodstream could cause [[endocarditis]] on valve that had previous lesion

| |

| *1885: Synthesized work of others relating to [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1899: Described streptococcal, staphylococcal, pneumococcal, and gonococcal endocarditis

| |

| *1903: First described "endocarditis lenta"

| |

| *1909: Credited by Osler as first to observe cutaneous nodes (named "Osler's nodes" by Libman) in patients with [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1909: Analyzed 150 cases of [[endocarditis]] and published diagnostic criteria relating to signs and symptoms

| |

| *1910: Described initial classification scheme to include "subacute endocarditis," with clinical signs/symptoms; absolute diagnosis required blood cultures

| |

| *1981: Described Beth Israel criteria based on strict case definitions

| |

| *1994: New criteria utilizing specific echocardiographic findings

| |

| *1995: Antibiotic treatment of adults with [[infective endocarditis]] caused by streptococci, enterococci, staphylococci, and HACEK (a) microorganisms

| |

| *1996: Modified [http://www.medcalc.com/endocarditis.html Duke Criteria] to allow serologic diagnosis of [[Coxiella burnetii]]

| |

| *1997: Guidelines for preventing bacterial [[endocarditis]]

| |

| *1997: Suggested modifications to Duke criteria for clinical diagnosis of native valve and prosthetic valve endocarditis: analysis of 118 pathologically proven cases

| |

| *1998: Guidelines for antibiotic treatment of streptococcal, enterococcal, and staphylococcal endocarditis

| |

| *1998: Antibiotic treatment of infective endocarditis due to viridans streptococci, enterococci, and other streptococci; recommendations for surgical treatment of endocarditis

| |

| *2000: Updated and modified [http://www.medcalc.com/endocarditis.html Duke Criteria]

| |

| *2002: [http://www.medcalc.com/endocarditis.html Duke Criteria] to include a molecular diagnosis of causal agents

| |

| *2001-3: Described etiology of Bartonella spp., [[Tropheryma whipplei]], and [[Coxiella burnetii]] in [[endocarditis]]

| |

|

| |

|

| == Epidemiology and Demographics == | | ==[[Endocarditis pathophysiology|Pathophysiology]]== |

|

| |

|

| The incidence of IE is approximately 2-4 cases per 100,000 persons per year worldwide. This rate has not changed in the past 5-6 decades.

| | ==[[Endocarditis causes|Causes]]== |

|

| |

|

| IE may occur in a person of any age. The frequency is increasing in elderly individuals, with 25-50% of cases occurring in those older than 60 years of age. The occurrence of IE is 3 times more common in males than in females.

| | ==[[Endocarditis differential diagnosis|Differentiating Endocarditis for other Disorders]]== |

|

| |

|

| == Risk Factors == | | ==[[Endocarditis risk factors|Risk Factors]]== |

|

| |

|

| '''Adults and children with underlying cardiac conditions placing them at ''highest risk'' for adverse outcomes of infective endocarditis (IE) including those with:'''

| | ==[[Endocarditis epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== |

| *Prosthetic cardiac valve or prosthetic cardiac valve repair

| |

| *Previous infective endocarditis

| |

| *Congenital heart disease (CHD) associated with

| |

| **Unrepaired cyanotic CHD, including palliative shunts and conduits

| |

| **Completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery or by catheter intervention, during the first 6 months after the procedure

| |

| **Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device (which inhibit endothelialization)

| |

| *Cardiac transplantation patients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

| |

|

| |

|

| == Screening == | | ==[[Endocarditis complications|Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis]]== |

|

| |

|

| Among those patients at high risk, careful monitoring should be undertaken to detect the early development of complications such as:

| | ==Diagnosis== |

| | [[Endocarditis diagnostic criteria|Diagnostic Criteria]] | [[Endocarditis history and symptoms|History and Symptoms]] | [[Endocarditis physical examination|Physical Examination and Signs]] | [[Endocarditis laboratory findings|Laboratory Findings]] | [[Endocarditis chest x ray|Chest X Ray]] | [[Endocarditis electrocardiogram|Electrocardiogram]] | [[Endocarditis cardiac MRI|Cardiac MRI]] | [[Endocarditis ct|CT]] | [[Endocarditis echocardiography and ultrasound|Echocardiography]] |

|

| |

|

| #Valvular dysfunction, usually insufficiency of the mitral or aortic valves;

| | ==Treatment== |

| #Myocardial or septal [[abscess]]es

| | [[Endocarditis medical therapy|Medical Therapy]] | | [[Endocarditis surgery|Surgery]] | [[Endocarditis antithrombotic therapy|Antithrombotic Therapy]] | [[Endocarditis primary prevention|Primary Prevention]] | [[Endocarditis secondary prevention|Secondary Prevention]] |

| #[[Congestive heart failure]]

| |

| #Metastatic infection

| |

| #Embolic phenomenon

| |

|

| |

|

| == Pathophysiology & Etiology== | | ==2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease== |

| | [[AHA Guidelines on Endocarditis Diagnosis and Follow-up|Diagnosis and Follow-up]] | [[AHA Guidelines on Endocarditis Medical Therapy|Endocarditis Medical Therapy Guidelines]] | [[AHA Guidelines on Endocarditis Intervention|Endocarditis Intervention Guidelines]] |

|

| |

|

| As previously mentioned, altered blood flow around the valves is a risk factor for the development of endocarditis. The valves may be damaged congenitally, from [[surgery]], by [[auto-immune]] mechanisms, or simply as a consequence of old age. The damaged part of a heart valve becomes covered with a blood clot, a condition known as non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE).

| | ==Case Studies== |

| | [[Endocarditis case study one|Case #1]] |

|

| |

|

| In a healthy individual, a [[bacteremia]] (where bacteria get into the blood stream through a minor cut or wound) would normally be cleared quickly with no adverse consequences. If a heart valve is damaged and covered with [[thrombus]], these structures can provide a nidus for bacteria to attach themselves and an infection can be established.

| | ==Related Chapters== |

| | | * [[Pacemaker endocarditis]] |

| The bacteremia is often caused by [[dentistry|dental]] procedures, such as a cleaning or [[Extraction (dental)|extraction]] of a [[tooth]]. It is important that a [[dentist]] or a [[dental hygienist]] therefore be told of any heart problems before beginning the procedure. Prophylactic [[antibiotics]] are administered to patients with certain heart conditions as a precaution.

| |

| | |

| Another cause of [[infective endocarditis]] is a scenario in which an excess number of bacteria enter the bloodstream. [[Colorectal cancer]], serious [[urinary tract infection]]s, and [[IV drug]] use can all introduce large numbers of such bacteria. When a large burden of bacteria are introduced, a normal heart valve may be infected. A more virulent organism (such as ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'', but see [[#Micro-organisms_responsible|below]] for others) is often responsible for infecting a normal valve.

| |

| | |

| Infections of the [[tricuspid valve]] and less frequently the [[pulmonic valve]] tend to occur in intravenous drug users given the high pathogen burden from their introduction in the [[vein]]. The diseased valve is most commonly affected when there is a pre-existing disease. In rheumatic heart disease this is the [[aortic valve]] and the [[mitral valve]]s, on the left side of the heart.

| |

| | |

| Complications of endocarditis can occur as a result of the locally destructive effects of the infection. These complications include perforation of valve leaflets, perforation of fistula between blood vessels or cardiac chambers, abscesses and disruption of conduction system.

| |

| | |

| == Natural History and Complications==

| |

| | |

| Complications of infective endocarditis include the following:

| |

| | |

| *'''Cardiac'''

| |

| #[[Murmur]]

| |

| #New aortic diastolic murmur suggests dilatation of the aortic annulus or eversion, rupture, or fenestration of an aortic leaflet

| |

| #Sudden onset of loud mitral pansystolic murmur suggests rupture of chorda tendineae or fenestration of a [[mitral valve]] leaflet

| |

| #[[Congestive heart failure]]

| |

| #[[Arrhythmias|Cardiac rhythm disturbances]]

| |

| #Occasionally, [[pericarditis]]

| |

| | |

| *'''Cutaneous'''

| |

| #[[Petechiae]] of the [[conjunctiva]], [[oropharynx]], [[skin]], and legs

| |

| #Linear subungual [[splinter haemorrhage]]s of the lower or middle nail bed

| |

| #[[Oslers nodes]]

| |

| #[[Janeway lesion]]s

| |

| | |

| *'''Musculoskeletal'''

| |

| #[[Myalgias]]

| |

| #[[Arthralgias]]

| |

| #[[Arthritis]]

| |

| #[[Low back pain]]

| |

| #[[Rheumatoid factor]] in up to 50% of patients with [[endocarditis]] for > 6 wk

| |

| #[[Clubbing|Clubbing of fingers]] in < 15% of patients

| |

| | |

| *'''Ocular'''

| |

| #[[hemorrhages|Petechial hemorrhages]],

| |

| #[[hemorrhages|Flame-shaped hemorrhages]],

| |

| #[[Roth's spot]]s,

| |

| #[[exudate|Cotton-wool exudates]] in the retina

| |

| | |

| *'''Embolic'''

| |

| #Significant [[emboli|arterial emboli]] occur in 30%–50% of patients, causing the following:

| |

| #:[[Stroke]]

| |

| #:[[blindness|Monocular blindness]]

| |

| #:[[abdominal pain|Acute abdominal pain]], [[ileus]], and [[melena]]

| |

| #:[[Pain]] and [[gangrene]] in the extremities

| |

| #[[emboli|CNS emboli]] are common

| |

| #[[emboli|Coronary emboli]], often asymptomatic, can cause [[myocardial infarction]]

| |

| #[[Pulmonary emboli]] common in right-sided [[endocarditis]], causing pulmonary infarcts or focal [[pneumonitis]]

| |

| | |

| *'''Splenic'''

| |

| #[[Splenomegaly]] in 15%–30% of patients

| |

| #[[Splenic |Splenic infarcts]] in up to 40% of patients

| |

| #[[Splenic |Splenic abscess]]es in ~ 5% of patients

| |

| | |

| *'''Renal'''

| |

| #[[hematuria|Microscopic hematuria]] in ~ 50% of patients

| |

| #Embolic renal infarction

| |

| #[[membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis|Diffuse membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis]]

| |

| | |

| *'''Mycotic aneurysms'''

| |

| Occur in any artery in 2%–8% of patients, causing the following:

| |

| #[[Pain]] or [[headache]]

| |

| #Pulsatile mass

| |

| #[[Fever]]

| |

| #[[hematoma|Sudden expanding hematoma]]

| |

| #Signs of major blood loss

| |

| | |

| *'''Neurologic'''

| |

| #Neurologic complications occur in 25%–40% of cases

| |

| #[[Stroke]]s caused by cerebral embolisms in ~ 15% of cases, causing the following:

| |

| #:[[consciousness|Altered level of consciousness]]

| |

| #:[[Seizures]]

| |

| #:Fluctuating focal neurologic signs

| |

| #Cerebral aneurysms occur in 1%–5% of cases, causing the following:

| |

| #:[[Headache]]

| |

| #:Focal signs

| |

| #:Acute [[intracerebral hemorrhage|intracerebral]] or [[subarachnoid hemorrhage]] caused by rupture

| |

| #:Mild meningeal irritation resulting from slow leakage

| |

| #[[Brain abscess]]es may occur in acute [[endocarditis]] caused by [[Staphylococcus aureus]]

| |

| #[[Seizure]]s

| |

| | |

| == Diagnosis ==

| |

| | |

| In general, a patient should fulfill the [http://www.medcalc.com/endocarditis.html Duke Criteria]<ref name=Durack>{{cite journal | author = Durack D, Lukes A, Bright D | title = New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. | journal = Am J Med | volume = 96 | issue = 3 | pages = 200-9 | year = 1994 | id = PMID 8154507}}</ref> in order to establish the diagnosis of [[endocarditis]].

| |

| | |

| As the [http://www.medcalc.com/endocarditis.html Duke Criteria] relies heavily on the results of [[echocardiography]], research has addressed when to order an [[echocardiogram]] by using signs and symptoms to predict occult endocarditis among patients with intravenous drug abuse<ref name=Weisse>{{cite journal | author = Weisse A, Heller D, Schimenti R, Montgomery R, Kapila R | title = The febrile parenteral drug user: a prospective study in 121 patients. | journal = Am J Med | volume = 94 | issue = 3 | pages = 274-80 | year = 1993 | id = PMID 8452151}}</ref><ref name=Samet>{{cite journal | author = Samet J, Shevitz A, Fowle J, Singer D | title = Hospitalization decision in febrile intravenous drug users. | journal = Am J Med | volume = 89 | issue = 1 | pages = 53-7 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 2368794}}</ref><ref name=Marantz>{{cite journal | author = Marantz P, Linzer M, Feiner C, Feinstein S, Kozin A, Friedland G | title = Inability to predict diagnosis in febrile intravenous drug abusers. | journal = Ann Intern Med | volume = 106 | issue = 6 | pages = 823-8 | year = 1987 | id = PMID 3579068}}</ref> and among non drug abusing patients <ref name=Leibovici>{{cite journal | author = Leibovici L, Cohen O, Wysenbeek A | title = Occult bacterial infection in adults with unexplained fever. Validation of a diagnostic index. | journal = Arch Intern Med | volume = 150 | issue = 6 | pages = 1270-2 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 2353860}}</ref><ref name=Mellors>{{cite journal | author = Mellors J, Horwitz R, Harvey M, Horwitz S | title = A simple index to identify occult bacterial infection in adults with acute unexplained fever. | journal = Arch Intern Med | volume = 147 | issue = 4 | pages = 666-71 | year = 1987 | id = PMID 3827454}}</ref>. ''Unfortunately, this research is over 20 years old and it is possible that changes in the epidemiology of [[endocarditis]] and bacteria such as [[staphylococcus]] make the following estimates incorrectly low.''

| |

| | |

| '''Among patients who do not use illicit drugs and have a [[fever]] in the emergency room''', there is a less than 5% chance of occult endocarditis. Mellors <ref name=Mellors>.</ref> in 1987 found no cases of endocarditis nor of [[staphylococcal]] bacteremia among 135 febrile patients ''in the emergency room''. The upper [http://medinformatics.uthscsa.edu/calculator/calc.shtml confidence interval] for 0% of 135 is 5%, so for statistical reasons alone, there is up to a 5% chance of endocarditis among these patients. In contrast, Leibovici <ref name=Leibovici>.</ref> found that among 113 non-selected adults ''admitted to the hospital'' because of fever there were two cases (1.8% with 95%CI: 0% to 7%) of [[endocarditis]].

| |

| | |

| '''Among patients who do use illicit drugs and have a fever in the emergency room''', there is about a 10% to 15% prevalence of [[endocarditis]]. This estimate is not substantially changed by whether the doctor believes the patient has a trivial explanation for their fever<ref name=Marantz>.</ref>. Weisse<ref name=Weisse>.</ref> found that 13% of 121 patients had endocarditis. Marantz <ref name=Marantz>.</ref> also found a prevalence of endocarditis of 13% among such patients in the emergency room with fever. Samet <ref name=Samet>.</ref> found a 6% incidence among 283 such patients, but after excluding patients with initially apparent major illness to explain the fever (including 11 cases of manifest endocarditis), there was a 7% prevalence of endocarditis.

| |

| | |

| '''Among patients with staphylococcal bacteremia (SAB)''', one study found a 29% prevalence of [[endocarditis]] in community-acquired SAB versus 5% in nosocomial SAB<ref name=Kaech>{{cite journal | author = Kaech C, Elzi L, Sendi P, Frei R, Laifer G, Bassetti S, Fluckiger U | title = Course and outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a retrospective analysis of 308 episodes in a Swiss tertiary-care centre. | journal = Clin Microbiol Infect | volume = 12 | issue = 4 | pages = 345-52 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16524411 | doi=10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01359.x}}</ref>. However, only 2% of strains were resistant to [[methicillin]] and so these numbers may be low in areas of higher resistance.

| |

| | |

| ===Common Causes===

| |

| | |

| Many types of organism can cause infective endocarditis. These are generally isolated by [[blood culture]], where the patient's blood is removed, and any growth is noted and identified.

| |

| | |

| Alpha-haemolytic [[Streptococcus|streptococci]], that are present in the mouth will often be the organism isolated if a dental procedure caused the bacteraemia.

| |

| | |

| If the bacteraemia was introduced through the skin, such as contamination in surgery, during catheterisation, or in an IV drug user, ''Staphylococcus aureus'' is common.

| |

| | |

| A third important cause of endocarditis is ''[[Enterococcus|Enterococci]]''. These bacteria enter the bloodstream as a consequence of abnormalities in the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts. ''[[Enterococcus|Enterococci]]'' are increasingly recognized as causes of nosocomial or hospital-acquired endocarditis. This contrasts with alpha-haemolytic streptococci and ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'' which are causes of community-acquired endocarditis.

| |

| | |

| Some organisms, when isolated, give valuable clues to the cause, as they tend to be specific.

| |

| *''[[Candida albicans]]'', a [[yeast]], is associated with IV drug users and the [[immunocompromised]]. Fungal endocarditis accounts for 5% of cases of native endocarditis and 10% of cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis. A diagnosis of fungal endocarditis is difficult, because many patients are afebrile with a normal white blood cell count (WBC). The fungus is often difficult to culture, and blood cultures typically negative. Fungal infections often result in large vegetations, systemic embolization, myocardial invasion, and are extremely resistant to medical therapy. Early surgical intervention is warranted because medical mortality approaches 100% Anti-fungal therapy for life is required. | |

| *''[[Pseudomonas]]'' species, which are very resilient organisms that thrive in water, may contaminate street drugs that have been contaminated with drinking water. [[Pseudomonas aeruginosa|P. aeruginosa]] can infect a child through foot punctures, and can cause both endocarditis and [[septic arthritis]].<ref>http://wordnet.com.au/Products/topics_in_infectious_diseases_Aug01.htm Topics in Infectious Diseases Newsletter, August 2001, Pseudomonas aeruginosa.</ref>

| |

| *''[[Streptococcus bovis]]'' and ''Clostridium septicum'', which are part of the natural flora of the bowel, are associated with [[colon cancer|colonic malignancies]]. When they present as the causative agent in endocarditis, it usually call for a concomitant [[colonoscopy]] due to worries regarding hematogenous spread of bacteria from the colon due to the neoplasm breaking down the barrier between the gut lumen and the blood vessels which drain the bowel.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1445-1433.2001.02231.x?cookieSet=1&journalCode=ans|title=Clostridium septicum and malignancy |author=Simon S. B. Chew, David Z. Lubowski|date=2001|source=ANZ Journal of Surgery 71 (11), 647–649}}</ref>

| |

| *''[[HACEK organisms]]'' are a group of bacteria that live on the dental gums, and can be seen with IV drug abusers who contaminate their needles with saliva. Patients may also have a history of poor dental hygiene, or pre-existing valvular disease.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic935.htm|title=HACEK Group Infections|author=Mirabelle Kelly, MD|date= June 7, 2005}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Differential Diagnosis of Risk Factors for or Causes of {{PAGENAME}}==

| |

| | |

| {|style="width:90%; height:100px" border="1"

| |

| |style="height:100px"; style="width:25%" border="1" bgcolor="LightSteelBlue" | '''Cardiovascular'''

| |

| |style="height:100px"; style="width:75%" border="1" bgcolor="Beige" | • [[Asymmetric septal hypertrophy]] • [[aortic stenosis | Calcific aortic stenosis]] • [[Cardiac catheterization]] • [[Cardiac surgery]] • [[Congenital Heart Disease]] • [[Mitral valve prolapse]] • [[Prosthetic heart valve]] • [[atrial septal defect|Septal defects]] • [[valvular heart disease|Valve disease]] • [[bacterial endocarditis|Previous bacterial endocarditis]] • [[Rheumatic Heart Disease]] • [[Sclerotherapy]] • [[Myxoma|Cardiac myxoma]]

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Chemical / poisoning'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Dental'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Dental extractions]] • [[Dental implants]] • [[Root canals]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Dermatologic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Skin infection]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Drug Side Effect'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[IV drug|IV drug use]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Ear Nose Throat'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Adenoidectomy]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Endocrine'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Environmental'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Gastroenterologic & Genito-Uriner'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Biliary tract|Biliary tract surgery]] • [[Cystoscopy]] • [[Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography]] • Urethral dilation • [[Prostatic|Prostatic surgery]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Genetic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Marfan's syndrome|Marfan's Syndrome]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Hematologic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Iatrogenic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Infectious Disease'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Diphtheria]] • [[Staphylococcus epidermidis]] • [[Staphylococcus aureus]] • [[Streptococcus bovis]] • [[Viridans streptococci]] • [[Group A streptococcus]] • [[Gram negative|Gram negative rods]] • [[Enterococuss]] • [[Candida]] • [[Tuberculosis]] • [[Salmonellosis]]

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Musculoskeletal / Ortho'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Neurologic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Nutritional / Metabolic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Obstetrics & Gynecology'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Childbirth]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Oncologic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Opthalmologic'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Overdose / Toxicity'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Psychiatric'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Pulmonary'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Respiratory infection]] • Respiratory tract procedures •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Renal / Electrolyte'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Rheum / Immune / Allergy'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • [[Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis]] • [[Polymyalgia rheumatica]] • [[Acute rheumatic fever]] • [[Polyarteritis nodosa]] • [[Systemic lupus erythematosus]] • [[Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome]] •

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Trauma'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| No underlying causes

| |

| |-

| |

| |-bgcolor="LightSteelBlue"

| |

| | '''Miscellaneous'''

| |

| |bgcolor="Beige"| • Surgical systemic-pulmonary shunts and conduits •

| |

| |-

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| === History and Symptoms ===

| |

| | |

| ====A. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis (SBE)====

| |

| *Insidious onset

| |

| *[[Fever]]

| |

| *[[Sweat]]s

| |

| *[[Weakness]]

| |

| *[[Myalgia]]s

| |

| *[[Arthralgia]]s

| |

| *[[Malaise]]

| |

| *[[Anorexia]]

| |

| *[[Fatigue]]

| |

| *[[Splenomegaly]], [[clubbing]], and [[Oslers nodes]] in long-standing SBE

| |

| | |

| ====B. Acute Bacterial Endocarditis====

| |

| | |

| *Abrupt onset

| |

| *[[Rigors]]

| |

| *[[Fever]]s as high as 102.9° to 105.1° F (39.4° to 40.6° C), often remittent

| |

| | |

| ====C. Endocarditis Associated with Parenteral Drug Use====

| |

| #[[fever|High fever]]s, [[chills]], [[rigors]], [[malaise]], [[cough]], and [[chest pain|pleuritic chest pain]]

| |

| #[[pulmonary emboli|Septic pulmonary emboli]] causing [[sputum]] production, [[hemoptysis]], and signs suggesting [[pneumonia]]

| |

| #[[murmur|Cardiac murmurs]]

| |

| #[[Tricuspid insufficiency]]

| |

| #Metastatic infections

| |

| #Neurologic manifestations

| |

| #Peripheral emboli

| |

| | |

| ====D. Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis====

| |

| #Occurs in 1%–2% of cases at 1 yr and in 4%–5% of cases at 4 yr after implantation

| |

| #Infection of perivalvular tissues

| |

| #Valvular dysfunction

| |

| #[[abscess|Myocardial abscesses]]

| |

| #[[Fever]]

| |

| #[[Petechiae]], [[Roth's spot]]s, [[Osler's nodes]], [[Janeway lesion]]s

| |

| #[[Emboli]]

| |

| | |

| === Physical Examination ===

| |

| | |

| ====Vital Signs====

| |

| | |

| A [[fever]] will likely be present. Rigors may be present.

| |

| | |

| ====Skin====

| |

| | |

| *[[Petechiae]] 10 - 40%

| |

| *[[Splinter haemorrhage]] 5 - 15%

| |

| *[[Oslers nodes]] 7 - 10% (tender subcutaneous nodules in pulp of digits)

| |

| *[[Janeway lesion]] 6 - 10% (erythematous, nontender lesions on palm or sole)

| |

| | |

| ==== Eyes ====

| |

| | |

| *[[Conjunctival hemorrhage]]

| |

| *[[Roth's spot]]s in the [[retina]]

| |

| [[Image:Roth-spot (white-centered hemorrhage - endocarditis).jpg|[[Roth's spot]]s (white centered hemorrhage)|right|thumb]]

| |

| {{clr}}

| |

| | |

| ==== Ear Nose and Throat ====

| |

| | |

| In patients in whom there is new acute onset of [[aortic regurgitation]], bobbing of the [[uvula]] may be present.

| |

| | |

| ==== Heart ====

| |

| *[[Murmur|Heart Murmur]]s: 80 - 85%

| |

| | |

| ==== Lungs ====

| |

| | |

| Signs of [[heart failure]] may present

| |

| | |

| ==== Abdomen ====

| |

| | |

| *[[Abdominal pain]] may be present due to mesenteric embolization or [[ileus]]

| |

| *[[Splenomegaly]] may be found in 15-30% patients. Left upper quadrant (LUQ) pain may be present as a result of a splenic infarct from embolization

| |

| *[[Flank pain]] may be present as a result of an embolus to the kidney

| |

| | |

| ==== Extremities ====

| |

| [[Image:Osler's Lesions (Endocarditis).jpg|Osler's nodes|right|thumb]]

| |

| *[[Janeway lesion]]s (painless hemorrhagic cutaneous lesions on the palms and soles)

| |

| *[[Gangrene]] of fingers may occur

| |

| *The fingers may show [[splinter haemorrhage]]s

| |

| *[[Osler's node]]s ([[lesions|painful subcutaneous lesions in the distal fingers]])

| |

| | |

| ==== Neurologic ====

| |

| | |

| [[Septic emboli]] may result in [[stroke]] and focal neurologic findings

| |

| | |

| [[Intracranial hemorrhage]] may occur

| |

| | |

| ==== Symptoms Frequency ====

| |

| | |

| *[[Fever]] 80 - 85%, often spiking

| |

| *[[Chills]] 42 - 75%

| |

| *[[Anorexia]] 25 - 55%

| |

| *[[Malaise]] 25 - 40%

| |

| *[[Weight loss]] 25 - 35%

| |

| *[[Back pain]]

| |

| *[[Stroke]] may be present in 10 - 15% of patients as a result of cerebral embolization

| |

| *[[Chest pain]] may be present as a result of embolzation in the coronary artery. The infarcts are usually not transmural. Pulmonary emboli, often septic, occur in 75% of patients with tricuspid endocarditis

| |

| * [[Abdominal pain]] may be present due to mesenteric embolization or [[ileus]]

| |

| * [[Blindness]] may be present due to retinal embolization in 3% of patients

| |

| | |

| === Laboratory Findings ===

| |

| | |

| An elevated [[erythrocyte sedimentation rate]] is present

| |

| | |

| A marked [[leukocytosis]] is present

| |

| | |

| A positive serum [[rheumatoid factor]] may be present (in approximately 50% of patients with subacute disease). It becomes negative after successful treatment.

| |

| | |

| The serum [[BUN]] and [[Cr]] may be elevated if [[glomerulonephritis]] is present

| |

| | |

| ====Urinalysis====

| |

| [[Glomerulonephritis]] may be present

| |

| | |

| ==== Electrocardiogram ====

| |

| | |

| There is no spesific [[EKG]] changes for diagnosis of [[Infective Endocarditis]]. [[EKG]] may help to detect the 10% of patients who develop a conduction delay during [[Infective Endocarditis]] by documenting an increased [[PR interval]].

| |

| | |

| ==== Chest X Ray ====

| |

| | |

| There are no specific [[chest x-ray]] findings specific for the diagnosis of endocarditis. Non specific findings would include findings of [[congestive heart failure]].

| |

| | |

| ==== MRI and CT ====

| |

| | |

| *A CT scan of the head should be obtained in patients who exhibit CNS symptoms or findings consistent with a mass effect (eg, macroabscess of the brain).

| |

| | |

| === Echocardiography===

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Vegetation on aortic valve in endocarditis.jpg|right|200px|thumb]]

| |

| Echocardiography is useful for risk stratification. Although the data are inconsistent, evidence suggests that vegetation size can predict embolic complications. In general, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is adequate for diagnosis of infective endocarditis in cases where cardiac structures-of-interest are well visualized.

| |

| | |

| Specific situations where transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is preferred over TTE include the presence of a prosthetic valvular device, suspected periannular complications, children with complex congenital cardiac lesions, patients with S. Aureus caused bacteremia and pre-existing valvular abnormalities that make TTE interpretation more difficult (e.g. calcific aortic stenosis).

| |

| | |

| The transthoracic echocardiogram has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 65% and 95% if the echocardiographer believes there is 'probabable' or 'almost certain' evidence of endocarditis<ref name=Shively>{{cite journal | author = Shively B, Gurule F, Roldan C, Leggett J, Schiller N | title = Diagnostic value of transesophageal compared with transthoracic echocardiography in infective endocarditis. | journal = J Am Coll Cardiol | volume = 18 | issue = 2 | pages = 391-7 | year = 1991 | id = PMID 1856406}}</ref><ref name=Erbel>{{cite journal | author = Erbel R, Rohmann S, Drexler M, Mohr-Kahaly S, Gerharz C, Iversen S, Oelert H, Meyer J | title = Improved diagnostic value of echocardiography in patients with infective endocarditis by transoesophageal approach. A prospective study. | journal = Eur Heart J | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 43-53 | year = 1988 | id = PMID 3345769}}</ref>.

| |

| | |

| === Aims of echocardiography ===

| |

| # Determine the presence, location and size of vegetations

| |

| # Assess the damage to the valve apparatus and determine the haemodynamic effects.

| |

| # The dimensions and function of the ventricles.

| |

| # Identify any abscess formation

| |

| # Need for surgical intervention.

| |

| | |

| === Echocardiographic features ===

| |

| * Irregular [[echogenic mass]] attached to valve leaflet

| |

| * attachment of the vegetation is on the upstream side of the valve leaflet

| |

| * independent movement of the mass (chaotic)

| |

| * minimum size of the vegetation identifiable on trans thoracic echocardiography is 3mm and by transoesophageal route is 2mm.

| |

| * With treatment and time, the vegetation shrinks and can get fibrosed or calcified - may not disappear completely.

| |

| * Large vegetations occur with fungal endocarditis or staph. aureus endocarditis.

| |

| * the haemodynamical effect is mostly due to regurgitation as a result of valve destruction.

| |

| | |

| === Local complications ===

| |

| * Abscess

| |

| * Fistula

| |

| * Perforation

| |

| * Prosthetic dehiscence

| |

| | |

| === When to do trans esophageal echocardiogram? ===

| |

| * Prosthetic valve endocarditis

| |

| * Poor trans thoracic views

| |

| * continuing sepsis in spite of adequate antibiotic therapy

| |

| * new PR prolongation

| |

| * No signs of endocarditis on trans thoracic echocardiography, but high clinical suspicion.

| |

| | |

| *Video 1: 2 D Echo shows Mitral Valve Vegetation,

| |

| <youtube v=5LogTcWG_u4/>

| |

| *Video 2: 2 D Echo shows Aortic and Mitral Valve Vegetations

| |

| <youtube v=fyrI9RR5DZY/>

| |

| *Video 3: 2D Echo Tricuspid Valve Vegetation

| |

| <googlevideo>-5198562295572873918&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| *Fungal Endocarditis 1

| |

| <googlevideo>7982129228294522803&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| *Fungal Endocarditis 2

| |

| <googlevideo>365208208714072490&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| *Fungal Endocarditis 3

| |

| <googlevideo>-4564538766847216719&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| *Fungal Endocarditis 4

| |

| <googlevideo>-6464177311760516420&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| *Fungal Endocarditis 5

| |

| <googlevideo>-6146773792630914635&hl=en</googlevideo>

| |

| | |

| ==== Other Imaging Findings ====

| |

| *Various radionuclide scans using, for example, gallium Ga 67–tagged white cells and indium In 111–tagged white cells, have proven to be of little use in diagnosing IE.

| |

| | |

| Radionuclide scans of the spleen are useful to help rule out a splenic abscess, which is a cause of bacteremia that is refractory to antibiotic therapy.

| |

| | |

| ===Pathology===

| |

| | |

| ====In acute phase====

| |

| | |

| * Aneurysms

| |

| * Infected thrombi or vegetations

| |

| * Valve ulcers or erosions

| |

| * Rupture of chordaes

| |

| * Endocardial jet lesions

| |

| * Flail leaflets or cusps

| |

| * Abcess formation (annular and ring)

| |

| | |

| ====In chronic phase====

| |

| | |

| * Perforations

| |

| * Nodular calcifications

| |

| * Tissue defects of valves

| |

| * Fibrosis of valves

| |

| | |

| ====Gross Pathology====

| |

| Images shown in this section are courtesy of Professor Peter G. Anderson D.V.M. PhD, and published with permission.

| |

| | |

| [http://peir.net © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology]

| |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:765.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent example of thrombi on [[aortic valve]].

| |

| Image:767.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Mitral valve]] lesion appears that have been present for at least several days.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:776.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) Perforated [[aortic valve]] cusp is shown.

| |

| Image:869.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Aortic valve]] with two small vegetations.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:872.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Mitral valve]] thrombi in chorda.

| |

| Image:1423.jpg|(Gross) A very good example of focal necrotizing lesions in distal portion of digit associated with bacterial endocarditis

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:1438.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) A lesion on non-coronary cusp of [[aortic valve]].

| |

| Image:1648.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent view of [[mitral valve|mitral]] scarring due to [[rheumatic fever]] healing infectious lesion.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:1662.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Aortic valve]] prosthesis ring infection extending into left atrium.

| |

| Image:1698.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent close-up view of [[mitral valve]] vegetations

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:1701.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) vegetations on [[mitral valve]] and left atrial endocardium due to [[actinomycosis]]

| |

| Image:1702.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent image of vegetation on [[aortic valve]]

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:1706.jpg|Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent image of vegetations on [[mitral valve]] evidence of rheumatic scarring

| |

| Image:1845.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Mitral valve]], an excellent example

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:1911.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) [[Mitral valve]]: an excellent image, identical to acute rheumatic lesion

| |

| Image:2030.jpg|Verrucous Nonbacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) An excellent example of an infant heart

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:2225.jpg|Purpura of cerebrum, cerebellum and brain stem in 36 years old female with [[Cushing syndrome]] and bacterial endocarditis caused by [[Staphylococcus aureus]]

| |

| Image:3181.jpg|Spleen infarct: (Gross) A typical small infarct with necrotic central portion (originated from infected marantic endocarditis on [[aortic valve|aortic]] and [[mitral valve]]s)

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:3183.jpg|Kidney infarct: (Gross) A natural color close-up and excellent image of yellow infarct marantic endocarditis on [[aortic valve|aortic]] and [[mitral valve]]s

| |

| Image:3802.jpg|Thrombotic Nonbacterial Endocarditis Infected: (Gross) Natural color of [[pulmonary valve]]. An excellent example of patient with [[multiple myeloma]]

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:9960.jpg|Thrombotic Non Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) Natural color of [[pulmonary valve]].

| |

| Image:9961.jpg|Thrombotic Non Bacterial Endocarditis: (Gross) Natural color and good example of [[tricuspid valve]] lesions

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:203196.jpg|[[Disseminated intravascular coagulation]] in endocarditis; [[tricuspid valve]] showing NBTE in [[DIC]]

| |

| Image:249017.jpg|Eye: Bacterial Endocarditis complicated as [[petechiae]]. Septic emboli to [[conjunctiva]]

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| ===Bacterial Endocarditis===

| |

| | |

| <youtube v=fH5DggA3q1w/>

| |

| | |

| ==Differential Diagnosis==

| |

| | |

| | |

| == Treatment ==

| |

| | |

| High dose [[antibiotic]]s are administered by the intravenous route to maximize diffusion of antibiotic molecules into vegetation(s) from the blood filling the chambers of the heart. This is necessary because neither the heart valves nor the vegetations adherent to them are supplied by blood vessels. Antibiotics are continued for a long time, typically two to six weeks. Specific drug regimens differ depending on the classification of the endocarditis as acute or subacute (acute necessitating treating for [[Staphylococcus aureus]] with [[oxacillin]] or [[vancomycin]] in addition to [[gram-negative]] coverage). [[Fungal]] [[endocarditis]] requires specific anti-fungal treatment, such as [[amphotericin B]].<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Surgical removal of the valve is necessary in patients who fail to clear micro-organisms from their blood in response to antibiotic therapy, or in patients who develop cardiac failure resulting from destruction of a valve by infection. A removed valve is usually replaced with an artificial valve which may either be mechanical (metallic) or obtained from an animal such as a pig; the latter are termed bioprosthetic valves.<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| [[Infective endocarditis]] is associated with a 10-25% mortality.

| |

| | |

| === Pharmacotherapy ===

| |

| | |

| Effective treatment requires identification of the etiologic agent and determination of its antimicrobial susceptibility.

| |

| | |

| Antibiotic therapy for subacute or indolent disease can be delayed until results of blood cultures are known; in fulminant infection or valvular dysfunction requiring urgent surgical intervention, begin empirical antibiotic therapy promptly after blood cultures have been obtained.

| |

| | |

| For prosthetic valve [[endocarditis]], treatment should be continued for 6–8 weeks.

| |

| | |

| ==== Acute Pharmacotherapies ====

| |

| | |

| =====Penicillin-Susceptible Viridans and Other Nonenterococcal Streptococci<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| The minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] <0.2 µg/ml

| |

| | |

| *[[Penicillin]] G: preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 12–18 million units I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4 weeks

| |

| | |

| *[[Penicillin]] G + [[gentamicin]] or [[ceftriaxone]]: preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[penicillin]] G, 12–18 million units I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4 weeks; [[gentamicin]], 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hour for 2 weeks (peak serum concentration should be ~ 3 µg/ml and trough concentrations < 1 µg/ml); [[ceftriaxone]], 2 g I.V. daily as a single dose for 2 weeks

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]]: for patients with history of [[penicillin]] [[hypersensitivity]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hour for 4 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====Relatively Penicillin-Resistant Streptococci<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| A- MIC 0.2–0.5 µg/ml

| |

| | |

| *[[Penicillin]] G + gentamicin: preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[penicillin]] G, 20–30 million units I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4 weeks; [[gentamicin]], 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hr for 2 wk (peak serum concentration should be ~ 3 µg/ml and trough concentrations < 1 µg/ml)

| |

| | |

| B- MIC > 0.5 µg/ml

| |

| | |

| *[[Penicillin]] G + [[gentamicin]]: preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[penicillin]] G, 20–30 million units I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4 week; [[gentamicin]], 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hour for 4 week (peak serum concentration should be ~ 3 µg/ml and trough concentrations < 1 µg/ml)

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]]: regimen for patients with history of [[penicillin]] [[hypersensitivity]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hour for 4 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====Enterococci<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Penicillin]] G + [[gentamicin]]: preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[penicillin]] G, 20–30 million units I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hr for 4–6 weeks; [[gentamicin]], 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hour for 4–6 weeks (peak serum concentration should be ~ 3 µg/ml and trough concentrations < 1 µg/ml)

| |

| | |

| *[[Ampicillin]] + [[gentamicin]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': ampicillin, 12 g I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4–6 weeks; [[gentamicin]], dose as above

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]] + [[gentamicin]]: regimen for patients with history of [[penicillin]] [[hypersensitivity]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[vancomycin]], 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hour for 4–6 weeks; [[gentamicin]], dose as above

| |

| | |

| =====Staphylococci (Methicillin Susceptible) in the Absence of Prosthetic Material<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Nafcillin]] or [[oxacillin]] + [[gentamicin]] (optional): preferred regimen

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[nafcillin]] or [[oxacillin]], 12 g I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4–6 weeks; [[gentamicin]], 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hr for 3–5 days (peak serum concentration should be ~ 3 µg/ml and trough concentrations <1 µg/ml)

| |

| | |

| *[[Cefazolin]] + [[gentamicin]] (optional): alternative regimen for patients with history of [[penicillin]] [[hypersensitivity]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[cefazolin]], 12 g I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 4–6 weeks; [[gentamicin]], dose as above

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]]: alternative regimen for patients with history of [[penicillin]] [[hypersensitivity]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hr for 4–6 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====Staphylococci (Methicillin Resistant) in the Absence of Prosthetic Material<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hour for 4–6 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====Staphylococci (Methicillin Susceptible) in the Presence of Prosthetic Material<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Nafcillin]] or [[oxacillin]] + [[rifampin]] + [[gentamicin]]

| |

|

| |

| '''Dose''': [[nafcillin]] or [[oxacillin]], 12 g I.V. daily in divided doses q. 4 hour for 6–8 weeks; rifampin, 300 mg p.o., q. 8 hour for 6–8 weeks; [[gentamicin]] (administer during the initial 2 weeks), 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hour for 2 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====Staphylococci (Methicillin Resistant) in the Presence of Prosthetic Material<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Vancomycin]] + [[rifampin]] + [[gentamicin]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': [[vancomycin]], 30 mg/kg I.V. daily in divided doses q. 12 hour for 6–8 weeks; [[rifampin]], 300 mg p.o., q. 8 hour for 6–8 weeks; [[gentamicin]] (administer during the initial 2 weeks), 3 mg/kg I.M. or I.V. daily in divided doses q. 8 hour for 2 weeks

| |

| | |

| =====[[HACEK organism|HACEK Organisms]]<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>=====

| |

| | |

| *[[Ceftriaxone]] or another [[cephalosporin|third-generation cephalosporin]]

| |

| | |

| '''Dose''': 2 g I.V. daily as a single dose for 4 weeks

| |

| | |

| ==== Antithrombotic Therapy<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>====

| |

| | |

| * [[Anticoagulant]]s can cause or worsen hemorrhage in patients with [[endocarditis]] but may be carefully administered when needed

| |

| * [[Prothrombin time]] should be carefully maintained at INR of 2.0–3.0

| |

| * Anticoagulation should be reversed immediately in the event of CNS complications and interrupted for 1–2 wk after acute embolic stroke

| |

| * Avoid [[heparin]] administration during active [[endocarditis]] if possible

| |

| | |

| ==== Chronic Pharmacotherapies <ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>====

| |

| | |

| === Surgery and Device Based Therapy ===

| |

| | |

| ==== Indications for Surgery ====

| |

| | |

| Indications for surgical debridement of vegetations and infected perivalvular tissue, with valve replacement or repair as needed are listed below:<ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| #Moderate to severe [[congestive heart failure]] due to valve dysfunction

| |

| #Unstable valve prosthesis

| |

| #Uncontrolled infection for > 1–3 week despite maximal antimicrobial therapy

| |

| #Persistent bacteremia

| |

| #[[endocarditis|Fungal endocarditis]]

| |

| #Relapse after optimal therapy (prosthesis)

| |

| #Vegetation in Situ

| |

| #Prosthetic valve [[endocarditis]] with perivalvular invasion

| |

| #[[Endocarditis]] caused by [[Pseudomonas aeruginosa]] or other gram-negative bacilli that has not responded after 7–10 days of maximal antimicrobial therapy

| |

| #Perivalvular extension of infection and abscess formation

| |

| #Staphylococcal infection of prosthesis

| |

| #Persistent fever (culture negative)

| |

| #Large vegetation (>10 mm = increased embolism)

| |

| #Relapse after optimal therapy (native valve)

| |

| #Vegetations that obstruct the valve orifice

| |

| | |

| ====Principles of Surgical Management====

| |

| #Excise all infected valve tissue

| |

| #Drain and debride abscess cavities

| |

| #Repair or replace damaged valves

| |

| #Repair associated pathology such as septal defect, fistulas <ref name= Baddour>{{cite journal | author = Baddour Larry M., Wilson Walter R., Bayer Arnold S., Fowler Vance G. Jr, Bolger Ann F., Levison Matthew E., Ferrieri Patricia, Gerber Michael A., Tani Lloyd Y., Gewitz Michael H., Tong David C., Steckelberg James M., Baltimore Robert S., Shulman Stanford T., Burns Jane C., Falace Donald A., Newburger Jane W., Pallasch Thomas J., Takahashi Masato, Taubert Kathryn A.| title = Infective Endocarditis: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association-Executive Summary: Endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. | journal = Circulation | volume = 111 | issue = 23 | pages = 3167-84 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15956145 }}</ref>

| |

| | |

| =====Aortic Valve - Surgical Options=====

| |

| If the infection limited is limited to the leaflets, then replace the aortic valve.

| |

| | |

| If the infection extends to anulus or beyond, then debride the infected tissues, drain any abscesses to the pericardial sac and replace the aortic root.

| |

| | |

| =====Atrioventricular Valve - Surgical Options=====

| |