Door-to-balloon: Difference between revisions

(/* 2013 Revised and 2009 and 2007 Focused Updates: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (DO NOT EDIT){{cite journal |author=O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. |title=2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the M...) |

(/* 2013 Revised and 2009 and 2007 Focused Updates: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (DO NOT EDIT){{cite journal |author=O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. |title=2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the M...) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

| colspan="1" style="text-align:center; background:LightGreen"|[[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Classification of Recommendations|Class I]] | | colspan="1" style="text-align:center; background:LightGreen"|[[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Classification of Recommendations|Class I]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| bgcolor="LightGreen"|<nowiki>"</nowiki>'''1.''' Reperfusion therapy should be administered to all eligible patients with STEMI with symptom onset within the prior 12 hours. ''([[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Level of Evidence|Level of Evidence: A]])<nowiki>"</nowiki> | | bgcolor="LightGreen"|<nowiki>"</nowiki>'''1.''' Reperfusion therapy should be administered to all eligible patients with STEMI with symptom onset within the prior 12 hours.<ref name="pmid7905143">{{cite journal |author= |title=Indications for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials of more than 1000 patients. Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group |journal=Lancet |volume=343 |issue=8893 |pages=311–22 |year=1994 |month=February |pmid=7905143 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid12517460">{{cite journal |author=Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL |title=Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials |journal=Lancet |volume=361 |issue=9351 |pages=13–20 |year=2003 |month=January |pmid=12517460 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7 |url=}}</ref> ''([[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Level of Evidence|Level of Evidence: A]])<nowiki>"</nowiki> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| bgcolor="LightGreen"|<nowiki>"</nowiki>'''2.''' [[STEMI]] patients presenting to a hospital with [[PCI]] capability should be treated with [[primary PCI]] within 90 minutes of first medical contact as a systems goal. ''([[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Level of Evidence|Level of Evidence: A]])<nowiki>"</nowiki> | | bgcolor="LightGreen"|<nowiki>"</nowiki>'''2.''' [[STEMI]] patients presenting to a hospital with [[PCI]] capability should be treated with [[primary PCI]] within 90 minutes of first medical contact as a systems goal. ''([[ACC AHA guidelines classification scheme#Level of Evidence|Level of Evidence: A]])<nowiki>"</nowiki> | ||

Revision as of 18:50, 19 December 2012

|

WikiDoc Resources for Door-to-balloon |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Door-to-balloon Most cited articles on Door-to-balloon |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Door-to-balloon |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Door-to-balloon at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Door-to-balloon Clinical Trials on Door-to-balloon at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Door-to-balloon NICE Guidance on Door-to-balloon

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Door-to-balloon Discussion groups on Door-to-balloon Patient Handouts on Door-to-balloon Directions to Hospitals Treating Door-to-balloon Risk calculators and risk factors for Door-to-balloon

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Door-to-balloon |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Door-to-balloon is a time measurement in emergency cardiac care (ECC), specifically in the treatment of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (or STEMI). The interval starts with the patient's arrival in the emergency department, and ends when a catheter guidewire crosses the culprit lesion in the cardiac cath lab. Because of the adage that "time is muscle", meaning that delays in treating a myocardial infarction increase the likelihood and amount of cardiac muscle damage due to localised hypoxia,[1][2][3][4] ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a door-to-balloon interval of no more than 90 minutes.[5] Currently fewer than half of STEMI patients receive reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention within the guideline-recommended timeframe.[6][7] It has become a core quality measure for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO).[8][9][10]

Improving door-to-balloon times

Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative

The benefit of prompt, expertly performed primary percutaneous coronary intervention over thrombolytic therapy for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction is now well established.[11] Few hospitals can provide PCI within the 90 minute interval,[12] which prompted the American College of Cardiology (ACC) to launch a national Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative in November of 2006. The D2B Alliance seeks to "take the extraordinary performance of a few hospitals and make it the ordinary performance of every hospital."[13] Over 800 hospitals have joined the D2B Alliance as of March 16, 2007.[14]

The D2B Alliance advocates six key evidence-based strategies and one optional strategy to help reduce door-to-balloon times:[13][15]

- ED physician activates the cath lab

- Single-call activation system activates the cath lab

- Cath lab team is available within 20-30 minutes

- Prompt data feedback

- Senior management commitment

- Team based approach

- (Optional) Prehospital 12 lead ECG activates the cath lab

Practical strategies at your site to reduce Door-to-Balloon times

The following strategies can be utilized to reduce door to balloon times:

- Have emergency medical service (EMS) personnel activate the cardiac catheterization laboratory directly

- Require that nurses, technicians and physicians remain within 30 minutes of the hospital while on call

- Require that nurses, technicians and physicians sleep in the hospital while on call

- Optimize door to EKG and EKG to decision times

- Activate the cardiac catheterization laboratory team with a single phone call using batch paging

- Have a "sterile table" prepared in the cardiac catheterization laboratory so that no time is wasted gathering equipment and supplies.

- Ask the CCU nurse and or ER nurse to assist the cath lab nurse in transporting and readying the patient for cardiac catheterization.

- Do not perform right heart catheterization or left heart catheterization before the intervention

- Only obtain venous access if the patient is hemodynamically unstable or if there is likely going to be the need to a temporary pacemaker

- Perform angiography of the culprit lesion first. There is a lack of consensus on this point. Some operators prefer to perform angiography of the non-culprit lesion first to assess the extent of disease. The Editor-In-Chief, CM Gibson prefers to assess the non-culprit lesion first. The non-culprit lesion may in fact turn out to be the culprit lesion.

Mission: Lifeline

On May 30, 2007, the American Heart Association launched 'Mission: Lifeline', a "community-based initiative aimed at quickly activating the appropriate chain of events critical to opening a blocked artery to the heart that is causing a heart attack."[16] It is seen as complementary to the ACC's D2B Initiative.[17] The program will concentrate on patient education to make the public more aware of the signs of a heart attack and the importance of calling 9-1-1 for emergency medical services (EMS) for transport to the hospital.[16] In addition, the program will attempt to improve the diagnosis of STEMI patients by EMS personnel.[16] According to Alice Jacobs, MD, who led the work group that addressed STEMI systems,[18] when patients arrive at non-PCI hospitals they will stay on the EMS stretcher with paramedics in attendance while a determination is made as to whether or not the patient will be transferred.[18] For walk-in STEMI patients at non-PCI hospitals, EMS calls to transfer the patient to a PCI hospital should be handled with the same urgency as a 9-1-1 call.[18]

EMS-to-balloon (E2B)

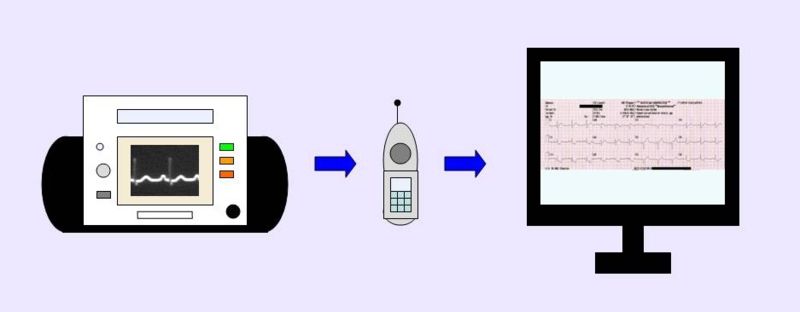

Although incorporating a prehospital 12 lead ECG into critical pathways for STEMI patients is listed as an optional strategy by the D2B Alliance, the fastest median door-to-balloon times have been achieved by hospitals with paramedics who perform 12 lead ECGs in the field.[19] EMS can play a key role in reducing the first-medical-contact-to-balloon time, sometimes referred to as EMS-to-balloon (E2B) time,[20] by performing a 12 lead ECG in the field and using this information to triage the patient to the most appropriate medical facility.[21][22][23]

Depending on how the prehospital 12 lead ECG program is structured, the 12 lead ECG can be transmitted to the receiving hospital for physician interpretation, interpreted on-site by appropriately trained paramedics, or interpreted on-site by paramedics with the help of computerized interpretive algorithms.[24] Some EMS systems utilize a combination of all three methods.[20] Prior notification of an in-bound STEMI patient enables time saving decisions to be made prior to the patient's arrival. This may include a "cardiac alert" or "STEMI alert" that calls in off duty personnel in areas where the cardiac cath lab is not staffed 24 hours a day.[20] The 30-30-30 rule takes the goal of achieving a 90 minute door-to-balloon time and divides it into three equal time segments. Each STEMI care provider (EMS, the emergency department, and the cardiac cath lab) has 30 minutes to complete its assigned tasks and seamlessly "hand off" the STEMI patient to the next provider.[20] In some locations, the emergency department may be bypassed altogether.[25]

Common themes in hospitals achieving rapid door-to-balloon times

Bradley et al. (Circulation 2006) performed a qualitative analysis of 11 hospitals in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction that had median door-to-ballon times = or < 90 minutes. They identified 8 themes that were present in all 11 hospitals:[7]

- An explicit goal of reducing door-to-balloon times

- Visible support of senior management

- Innovative, standardized protocols

- Flexibility in implementing standardized protocols

- Uncompromising individual clinical leaders

- Collaborative interdisciplinary teams

- Data feedback to monitor progress and identify problems or successes

- Organizational culture that fostered persistence despite challenges and setbacks

Criteria for an ideal primary PCI center

Granger et al. (Circulation 2007) identified the following criteria of an ideal primary PCI center.[24]

Institutional resources

- Primary PCI is the routine treatment for eligible STEMI patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

- Primary PCI is performed as soon as possible

- Institution is capable of providing supportive care to STEMI patients and handling complications

- Written commitment by hospital administration to support the program

- Identifies physician director for PCI program

- Creates multidisciplinary group that includes input from all relevant stakeholders, including cardiology, emergency medicine, nursing, and EMS

- Institution designs and implements a continuing education program

- For institution without on-site surgical backup, there is a written agreement with tertiary institution and EMS to provide for rapid transfer of STEMI patients when needed

Physician resources

- Interventional cardiologists meet ACC/AHA criteria for competence

- Interventional cardiologists participate in, and are responsive to formal on-call schedule

Program requirements

- Minimum of 36 primary PCI procedures and 400 total PCI procedures annually

- Program is described in a "manual of operations" that is compliant with ACC/AHA guidelines

- Mechanisms for monitoring program performance and ongoing quality improvement activities

Other features of ideal system

- Robust data collection and feedback including door-to-balloon time, first door-to-balloon time (for transferred patients), and the proportion of eligible patients receiving some form of reperfusion therapy

- Earliest possible activation of the cardiac cath lab, based on prehospital ECG whenever possible, and direct referral to PCI-hospital based on field diagnosis of STEMI

- Standardized ED protocols for STEMI management

- Single phone call activation of cath lab that does not depend on cardiologist interpretation of ECG

Gaps and barriers to timely access to primary PCI

Granger et al. (Circulation 2007) identified the following barriers to timely access to primary PCI.[24]

- Busy PCI hospitals may have to divert patients

- Significant delays in ED diagnosis of STEMI may occur, particularly when patient does not arrive by EMS

- Manpower and financial considerations may prevent smaller PCI programs from providing primary PCI for STEMI 24 hours a day

- Reimbursement for optimal coordination of STEMI patients needs to be realigned to reflect performance

- In most PCI centers, cath lab staff is off-site during off hours, requiring a mandate that staff report with 20-30 minutes of cath lab activation

2013 Revised and 2009 and 2007 Focused Updates: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (DO NOT EDIT)[26][27][5]

Regional Systems of STEMI Care, Reperfusion Therapy, and Time-to-Treatment Goals (DO NOT EDIT)[26]

| Class I |

| "1. All communities should create and maintain a regional system of STEMI care that includes assessment and continuous quality improvement of emergency medical services and hospital-based activities. Performance can be facilitated by participating in programs such as Mission: Lifeline and the Door-to-Balloon Alliance.[28][29][30][31] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

Triage and Transfer for PCI (DO NOT EDIT)[27]

| Class IIa |

| "1. It is reasonable for high-risk patients who receive fibrinolytic therapy as primary reperfusion therapy at a non–PCI-capable facility to be transferred as soon as possible to a PCI-capable facility where PCI can be performed either when needed or as a pharmacoinvasive strategy. Consideration should be given to initiating a preparatory antithrombotic (anticoagulant plus antiplatelet) regimen before and during patient transfer to the catheterization laboratory. [32][33](Level of Evidence: B) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1. Patients who are not at high risk who receive fibrinolytic therapy as primary reperfusion therapy at a non–PCI-capable facility may be considered for transfer as soon as possible to a PCI-capable facility where PCI can be performed either when needed or as a pharmacoinvasive strategy. Consideration should be given to initiating a preparatory antithrombotic (anticoagulant plus antiplatelet) regimen before and during patient transfer to the catheterization laboratory. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

Reperfusion (DO NOT EDIT) [26][5]

| Class I |

| "1. Reperfusion therapy should be administered to all eligible patients with STEMI with symptom onset within the prior 12 hours.[34][35] (Level of Evidence: A)" |

| "2. STEMI patients presenting to a hospital with PCI capability should be treated with primary PCI within 90 minutes of first medical contact as a systems goal. (Level of Evidence: A)" |

| "3. STEMI patients presenting to a hospital without PCI capability and who cannot be transferred to a PCI center and undergo PCI within 90 minutes of first medical contact should be treated with fibrinolytic therapy within 30 minutes of hospital presentation as a systems goal unless fibrinolytic therapy is contraindicated. (Level of Evidence: B)" |

References

- ↑ Soon CY, Chan WX, Tan HC (2007). "The impact of time-to-balloon on outcomes in patients undergoing modern primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction". Singapore medical journal. 48 (2): 131–6. PMID 17304392.

- ↑ Arntz HR, Bossaert L, Filippatos GS (2005). "European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 5. Initial management of acute coronary syndromes". Resuscitation. 67 Suppl 1: S87–96. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.003. PMID 16321718.

- ↑ De Luca G, van't Hof AW, de Boer MJ; et al. (2004). "Time-to-treatment significantly affects the extent of ST-segment resolution and myocardial blush in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty". Eur. Heart J. 25 (12): 1009–13. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.021. PMID 15191770.

- ↑ Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT; et al. (2000). "Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction". JAMA. 283 (22): 2941–7. PMID 10865271.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW; et al. (2008). "2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration With the Canadian Cardiovascular Society endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Writing on Behalf of the 2004 Writing Committee". Circulation. 117 (2): 296–329. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188209. PMID 18071078. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gibson CM, Pride YB, Frederick PD; et al. (2008). "Trends in reperfusion strategies, door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times, and in-hospital mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction enrolled in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006". Am. Heart J. 156 (6): 1035–44. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.029. PMID 19032997. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bradley EH, Curry LA, Webster TR; et al. (2006). "Achieving rapid door-to-balloon times: how top hospitals improve complex clinical systems". Circulation. 113 (8): 1079–85. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590133. PMID 16490818.

- ↑ National Hospital Quality Measures/The Joint Commission Core Measures Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Retrieved on June 30, 2007.

- ↑ Larson DM, Sharkey SW, Unger BT, Henry TD (2005). "Implementation of acute myocardial infarction guidelines in community hospitals". Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 12 (6): 522–7. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.008. PMID 15930403.

- ↑ Williams SC, Schmaltz SP, Morton DJ, Koss RG, Loeb JM (2005). "Quality of care in U.S. hospitals as reflected by standardized measures, 2002-2004". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (3): 255–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa043778. PMID 16034011.

- ↑ Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. (2003). "Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials". Lancet. 361 (9351): 13–20. PMID 12517460.

- ↑ Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y; et al. (2006). "Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (22): 2308–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa063117. PMID 17101617. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 John Brush, MD, "The D2B Alliance for Quality," STEMI Systems Issue Two, May 2007. Accessed July 2, 2007.

- ↑ "D2B: An Alliance for Quality". American College of Cardiology. 2006. Unknown parameter

|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) - ↑ "D2B Strategies Checklist". American College of Cardiology. 2006. Unknown parameter

|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Mission: Lifeline - a new plan to decrease deaths from major heart blockages," American Heart Association, May 31, 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- ↑ ACC Targets STEMI Times with Emergency CV Care 2007, Accessed July 3, 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Michael O'Riordan, "AHA Announces Mission: Lifeline, a New Initiative to Improve Systems of Care for STEMI Patients," Heartwire (a professional news service of WebMD), May 31, 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- ↑ Bradley EH, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ; et al. (2005). "Achieving door-to-balloon times that meet quality guidelines: how do successful hospitals do it?". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46 (7): 1236–41. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.009. PMID 16198837.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Rokos I. and Bouthillet T., "The emergency medical systems-to-balloon (E2B) challenge: building on the foundations of the D2B Alliance," STEMI Systems, Issue Two, May 2007. Accessed June 16, 2007.

- ↑ Rokos IC, Larson DM, Henry TD; et al. (2006). "Rationale for establishing regional ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks". Am. Heart J. 152 (4): 661–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.001. PMID 16996830.

- ↑ Moyer P, Feldman J, Levine J; et al. (2004). "Implications of the Mechanical (PCI) vs Thrombolytic Controversy for ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction on the Organization of Emergency Medical Services: The Boston EMS Experience". Crit Pathw Cardiol. 3 (2): 53–61. doi:10.1097/01.hpc.0000128714.35330.6d. PMID 18340140. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Henry TD, Atkins JM, Cunningham MS; et al. (2006). "ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: recommendations on triage of patients to heart attack centers: is it time for a national policy for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction?". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47 (7): 1339–45. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.101. PMID 16580518. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Granger CB, Henry TD, Bates WE, Cercek B, Weaver WD, Williams DO (2007). "Development of Systems of Care for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients. The Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction-Receiving) Hospital Perspective". doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.184049. PMID 17538039.

- ↑ David Jaslow, MD, "Out-of-Hospital STEMI Alert - If Time is Muscle, What's Taking So Long? EMS Responder, March 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD; et al. (2012). "2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84. PMID 23247303. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, King SB, Anderson JL, Antman EM; et al. (2009). "2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 120 (22): 2271–306. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192663. PMID 19923169.

- ↑ Aguirre FV, Varghese JJ, Kelley MP; et al. (2008). "Rural interhospital transfer of ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients for percutaneous coronary revascularization: the Stat Heart Program". Circulation. 117 (9): 1145–52. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728519. PMID 18268151. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Henry TD, Sharkey SW, Burke MN; et al. (2007). "A regional system to provide timely access to percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction". Circulation. 116 (7): 721–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694141. PMID 17673457. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Jollis JG, Roettig ML, Aluko AO; et al. (2007). "Implementation of a statewide system for coronary reperfusion for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction". JAMA. 298 (20): 2371–80. doi:10.1001/jama.298.20.joc70124. PMID 17982184. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Le May MR, So DY, Dionne R; et al. (2008). "A citywide protocol for primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (3): 231–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073102. PMID 18199862. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, et al. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 2705–18.

- ↑ Di Mario C, Dudek D, Piscione F, et al. Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the Combined Abciximab REteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI): an open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008; 371: 559–68.

- ↑ "Indications for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials of more than 1000 patients. Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group". Lancet. 343 (8893): 311–22. 1994. PMID 7905143. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL (2003). "Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials". Lancet. 361 (9351): 13–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. PMID 12517460. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

External links

- The MD TV: Comments on Hot Topics, State of the Art Presentations in Cardiovascular Medicine, Expert Reviews on Cardiovascular Research

- Clinical Trial Results: An up to dated resource of Cardiovascular Research

- American College of Cardiology (ACC) Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative

- Q&A: Improving door-to-balloon time for acute MI - American College of Physicians

- Reducing Door to Balloon Time for Acute Myocardial Infarction in a Tertiary Emergency Department - A report by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement

- Regional PCI for STEMI resource center - Evidence based resource center for the development of regional PCI networks for acute STEMI

- STEMI Systems Quarterly newsletter for STEMI care professionals

Media coverage

- "Hospitals too slow on heart attacks," USA Today, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals Join to Speed Care After Heart Attacks," The New York Times, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Saving Time, Saving Lives," ABC News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Heart Attack Care In Critical Condition," CBS News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals Seek to Speed Up Emergency Heart Attack Care," Fox News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals race to improve heart attack care," MSNBC.com, November 14, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.