Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology

|

Cardiac amyloidosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor: Aarti Narayan, M.B.B.S [2]; Raviteja Guddeti, M.B.B.S. [3]

Overview

The characteristic feature of cardiac amyloidosis is abnormal deposition of abnormally folded light chains of several serum proteins, making them insoluble and accumulate in various organs. This abnormal folding of proteins is most commonly a result of genetic mutations or excessive formation. Involvement of cardiac muscle can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias and advanced conduction disorder [1].

Pathophysiology

As mentioned above, amyloidosis is characterized by the deposition and extracellular accumulation of fibrillary proteins, leading to the loss of normal tissue architecture[2]. Various proteins are capable of undergoing abnormal beta pleated folding to form amyloid protein. The most common culprit protein responsible for forming amyloid deposits are the light chains of immunoglobulins produced by the plasma cells in bone marrow. More than 5 - 10% of bone marrow content filled with plasma cells is a poor prognostic indicator. The lambda (λ) chains are more likely to be involved in amyloid deposit formation than the kappa (κ) chains.

Most frequent types of cardiac amyloidosis are:

- Acquired monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis

- Hereditary transthyretin (TTR)-related form

- Non-mutant TTR-related amyloidosis

- Senile amyloidosis

All three forms frequently involve the myocardium, with the light chain amyloidosis (AL) being the most common[3][4].

Acquired monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis (AL)

- Monoclonal gammopathy of benign type is the most common form associated with AL cardiac amyloidosis. The abnormally folded light chains produced by defective plasma cells deposit in tissues resulting in disruption of tissue architecture by causing free radical damage and organ dysfunction.

- AL cardiac amyloidosis is rarely seen with multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia and lymphomas.

- Caused by greater than 100 mutations of TTR

- The protein is synthesized by the liver

Familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy

- Defined as presence of TTR mutation that primarily affects the myocardium and without significant neuropathy.[7]

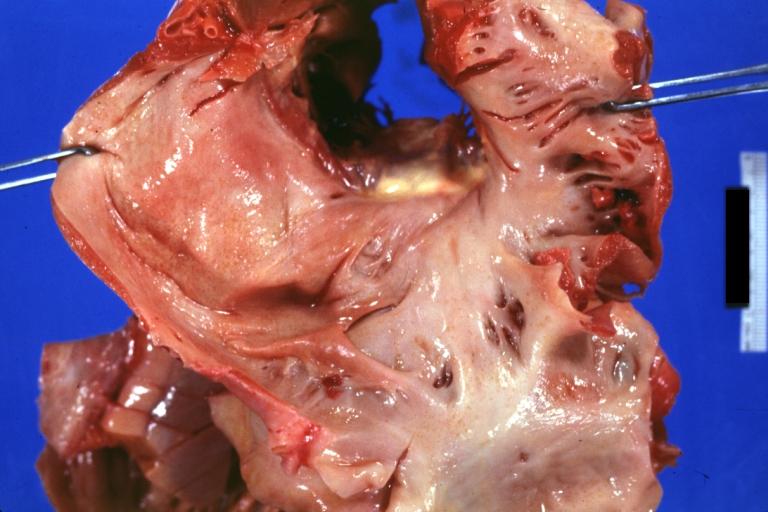

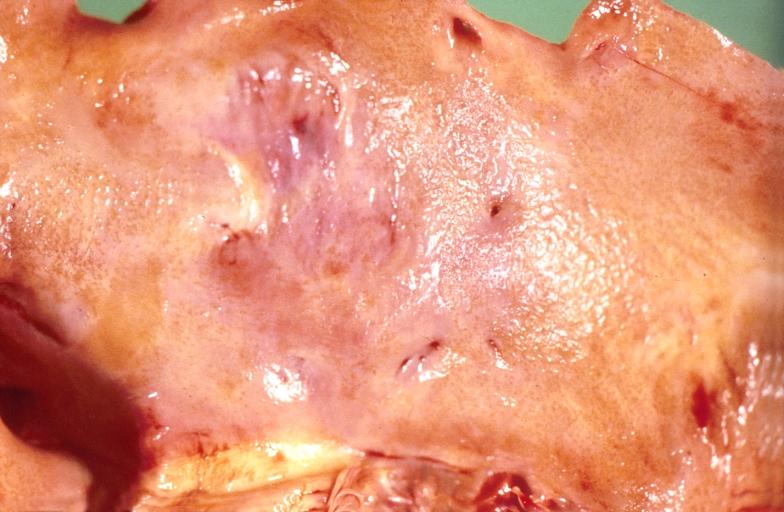

Gross Pathology

The cardiac amyloid deposits are most commonly seen in the myocardium, but can also be seen in atria, pericardium, endocardium and microvasculature.

- On gross examination, the myocardium is thicker and rubbery in consistency. More than half of myocardium involvement is common in the AL type of cardiac amyloidosis.

- The size of ventricular cavity remains unchanged, however filling of the ventricles is restricted (causing restrictive cardiomyopathy) because of the stiffening of ventricular wall as a result of deposition of amyloid material.

- Pericardial effusion and valvular dysfunction is common from pericardial and endocardial involvement. Intracardiac thrombus formation is seen in [8][9][10]

-

Amyloidosis Lesion In Left Atrium: Gross natural color view of a diagnostic lesion

-

Amyloidosis Lesion In Left Atrium: Gross natural color close-up

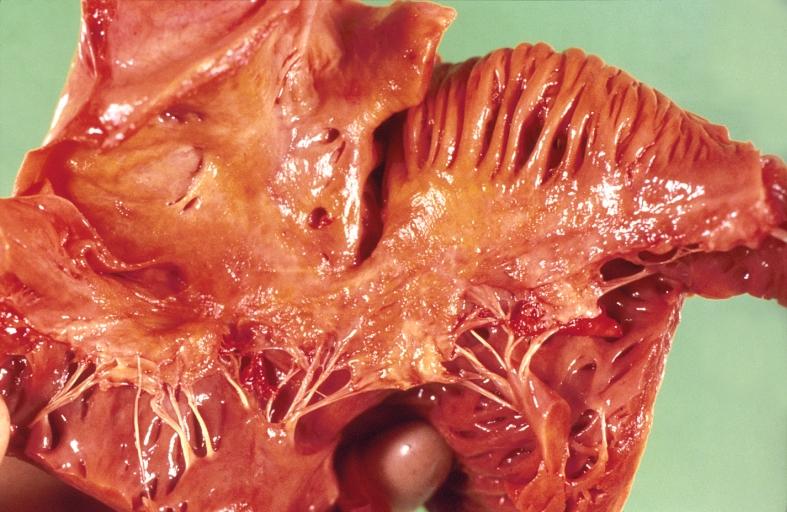

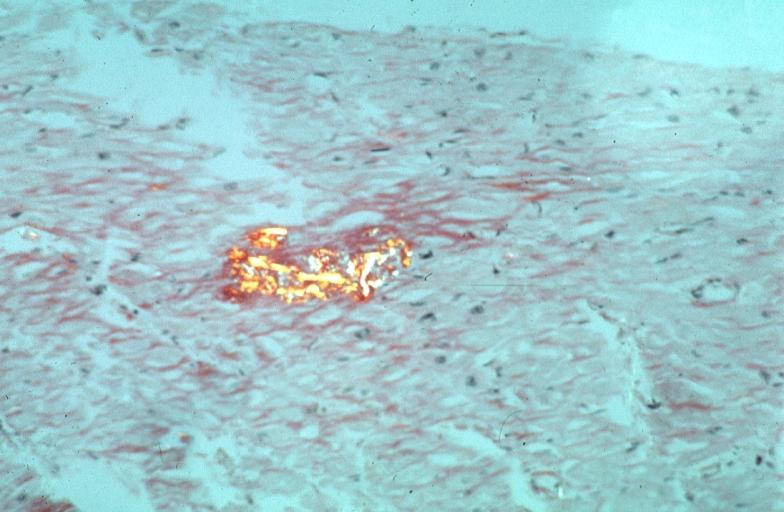

Microscopic Pathology

-

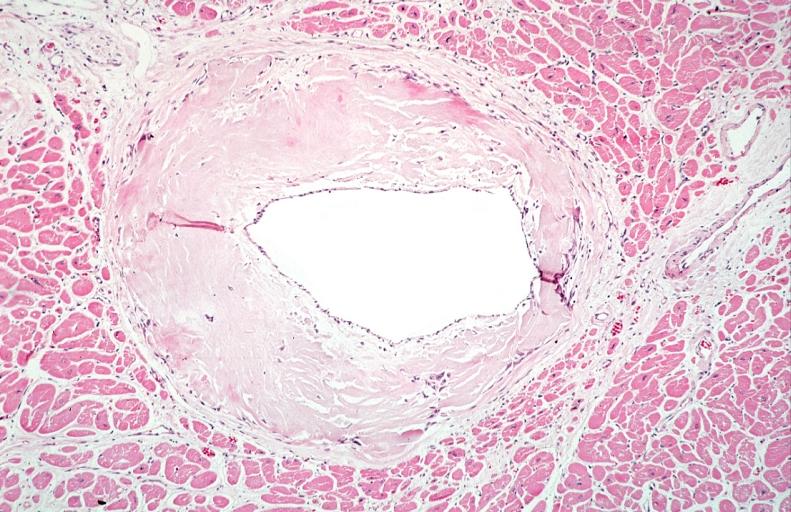

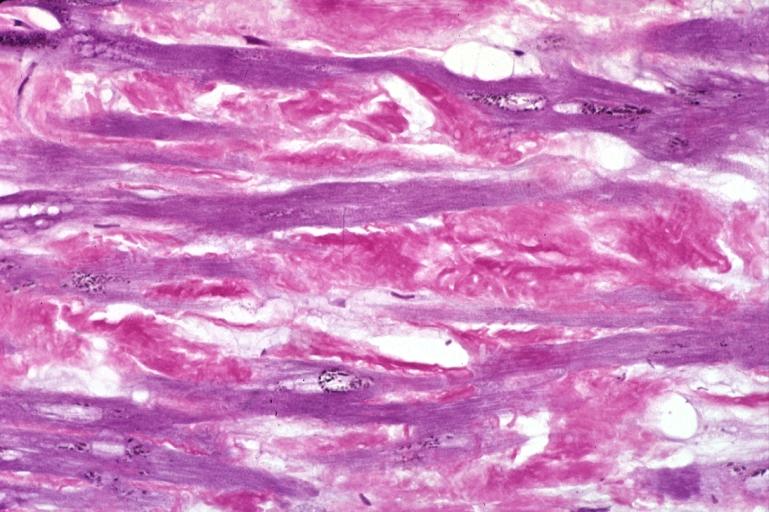

Heart: Perivascular amyloid, amyloidosis, congo red showing birefringence

-

Heart: Perivascular amyloid, amyloidosis (Hematoxylin and eosin staining)

References

- ↑ Dharmarajan K, Maurer MS (2012). "Transthyretin cardiac amyloidoses in older North Americans". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 765–74. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03868.x. PMC 3325376. PMID 22329529. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Merlini G, Bellotti V (2003). "Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (6): 583–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMra023144. PMID 12904524. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Falk RH, Comenzo RL, Skinner M (1997). "The systemic amyloidoses". The New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (13): 898–909. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709253371306. PMID 9302305. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A (1999). "Amyloidosis: recognition, confirmation, prognosis, and therapy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 74 (5): 490–4. doi:10.4065/74.5.490. PMID 10319082. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hodkinson HM, Pomerance A (1977). "The clinical significance of senile cardiac amyloidosis: a prospective clinico-pathological study". The Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 46 (183): 381–7. PMID 918253. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Lie JT, Hammond PI (1988). "Pathology of the senescent heart: anatomic observations on 237 autopsy studies of patients 90 to 105 years old". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 63 (6): 552–64. PMID 3374172. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Buxbaum JN, Tagoe CE (2000). "The genetics of the amyloidoses". Annual Review of Medicine. 51: 543–69. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.543. PMID 10774481. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ Nakagawa M, Tojo K, Sekijima Y, Yamazaki KH, Ikeda S (2012). "Arterial thromboembolism in senile systemic amyloidosis: report of two cases". Amyloid : the International Journal of Experimental and Clinical Investigation : the Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis. 19 (2): 118–21. doi:10.3109/13506129.2012.685131. PMID 22583098. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Van de Veire NR, Dierick J, De Sutter J (2012). "Intracardiac emboli as first presentation of cardiac AL amyloidosis". European Heart Journal. 33 (7): 818. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr330. PMC 3345559. PMID 21893485. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Feng D, Edwards WD, Oh JK; et al. (2007). "Intracardiac thrombosis and embolism in patients with cardiac amyloidosis". Circulation. 116 (21): 2420–6. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.697763. PMID 17984380. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)