Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Isolated Atrial Amyloidosis=== | ===Isolated Atrial Amyloidosis=== | ||

* This condition is most commonly from excess production of abnormally folded [[atrial natriuretic peptide]], like in [[congestive cardiac failure]]<ref name="pmid22536133">{{cite journal |author=Millucci L, Ghezzi L, Bernardini G, Braconi D, Tanganelli P, Santucci A |title=Prevalence of isolated atrial amyloidosis in young patients affected by congestive heart failure |journal=[[TheScientificWorldJournal]] |volume=2012 |issue= |pages=293863 |year=2012 |pmid=22536133 |pmc=3317626 |doi=10.1100/2012/293863 |url=}}</ref>. | * This condition is most commonly from excess production of abnormally folded [[atrial natriuretic peptide]], like in [[congestive cardiac failure]]<ref name="pmid22536133">{{cite journal |author=Millucci L, Ghezzi L, Bernardini G, Braconi D, Tanganelli P, Santucci A |title=Prevalence of isolated atrial amyloidosis in young patients affected by congestive heart failure |journal=[[TheScientificWorldJournal]] |volume=2012 |issue= |pages=293863 |year=2012 |pmid=22536133 |pmc=3317626 |doi=10.1100/2012/293863 |url=}}</ref>. | ||

* | * Increased incidence of atrial fibrillation has been noted in patients with isolated atrial amyloidosis<ref name="pmid12379579">{{cite journal |author=Röcken C, Peters B, Juenemann G, ''et al.'' |title=Atrial amyloidosis: an arrhythmogenic substrate for persistent atrial fibrillation |journal=[[Circulation]] |volume=106 |issue=16 |pages=2091–7 |year=2002 |month=October |pmid=12379579 |doi= |url=}}</ref>. | ||

===Gross Pathology=== | ===Gross Pathology=== | ||

Revision as of 23:42, 4 May 2013

|

Cardiac amyloidosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Cardiac amyloidosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor: Aarti Narayan, M.B.B.S [2]; Raviteja Guddeti, M.B.B.S. [3]

Overview

The characteristic feature of cardiac amyloidosis is abnormal deposition of abnormally folded light chains of several serum proteins, making them insoluble and accumulate in various organs. This abnormal folding of proteins is most commonly a result of genetic mutations or excessive formation. Involvement of cardiac muscle can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias and advanced conduction disorder [1].

Pathophysiology

As mentioned above, amyloidosis is characterized by the deposition and extracellular accumulation of fibrillary proteins, leading to the loss of normal tissue architecture[2]. Various proteins are capable of undergoing abnormal beta pleated folding to form amyloid protein. The most common culprit protein responsible for forming amyloid deposits are the light chains of immunoglobulins produced by the plasma cells in bone marrow.

Most frequent types of cardiac amyloidosis are:

- Acquired monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis

- Familial or hereditary transthyretin (TTR)-related form

- Non-mutant TTR-related amyloidosis (systemic senile amyloidosis)

All these forms frequently involve the myocardium, with the light chain amyloidosis (AL) being the most common[3][4].

Acquired monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis (AL)

- Monoclonal gammopathy of benign type is the most common form associated with AL cardiac amyloidosis. The abnormally folded light chains produced by defective plasma cells deposit in tissues resulting in disruption of tissue architecture by causing free radical damage and organ dysfunction.

- More than 5 - 10% of bone marrow content filled with plasma cells is a poor prognostic indicator. The lambda (λ) chains are more likely to be involved in amyloid deposit formation than the kappa (κ) chains.

- AL cardiac amyloidosis is rarely seen with multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia and lymphomas.

Hereditary Transthyretin (TTR)-Related Form (ATTR)

- The hereditary or familial form of cardiac amyloidosis is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Mutations leading to substitution of a single amino acid on the protein chain can cause abnormal spacial configuration of the protein, leading to its abnormal deposition in the inter-cellular space.

- The mutations in the genes producing various proteins like transthyretin, fibrinogen, apolipoprotein A1 and A2 are responsible. However, the transthyretin mutation is by far the commonest cause of hereditary cardiac amyloidosis.

- Transthyretin, a protein tetramer synthesized in the liver, is responsible for transport of the thyroid hormone and vitamin A in the body. The extent of myocardial involvement varies with the gene sequence mutated in the transthyretin gene.

- About 90 to 100% patients with "Thr60Ala" mutation, where alanine is substituted for threonine at the 60th position on the transthyretin protein and the "Val122Ile", in which isoleucine is substituted for valine at the 122nd amino acid position, have severe restrictive cardiomyopathy at presentation.

- Whereas the "Val30Met" mutation of transthyretin have cardiac involvement only in the elderly patients, with peripheral and autonomic nervous system being the primary target. The Val30Met mutation is normally present in 3.9% of all African Americans and in about 23% of African Americans with cardiac amyloidosis [5].

- Cardiac involvement in rare in other variant ATTR like mutations in apolipoprotein A1 and secondary amyloidosis. These more often involve the liver and kidneys.

- Amyloid deposits are found in the hearts of approximately 25% of elderly patients at autopsy[5]. The clinical significance of these amyloid deposits have not yet been elucidated, although excess deposition leading to symptoms has been shown to be associated with increased mortality, with a median survical of 7 years[6][7][8].

- This type of amyloidosis predominantly involves the heart, with the exception of carpel tunnel syndrome, which presents about 3 to 4 years before cardiac failure.

- This disorder shows male preponderance and commonly presents after 60 years of age. This condition is often misdiagnosed as chronic hypertension, but recent diagnostic techniques like cardiac MRI have made possible the diagnosis of this condition. It is probably the most common form of amyloidosis in the United States.

- Senile systemic amyloidosis has been associated with increased incidence of myocardial infarctions[9] and atrial fibrillation[10] in various studies. The association of tau protein with occurrence of this condition has raised the question of correlation of senile systemic amyloidosis with Alzheimer's disease.

Isolated Atrial Amyloidosis

- This condition is most commonly from excess production of abnormally folded atrial natriuretic peptide, like in congestive cardiac failure[11].

- Increased incidence of atrial fibrillation has been noted in patients with isolated atrial amyloidosis[10].

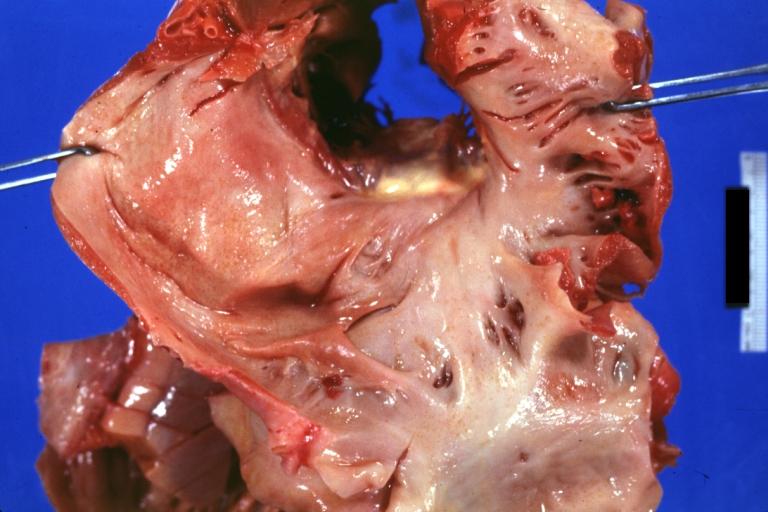

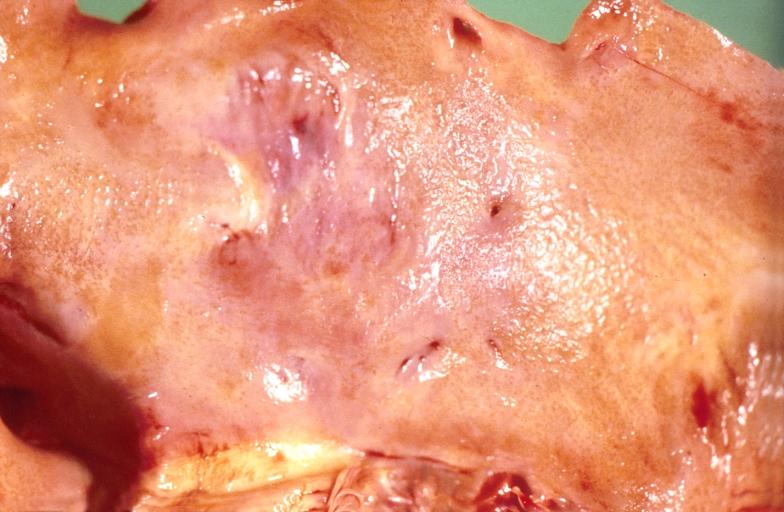

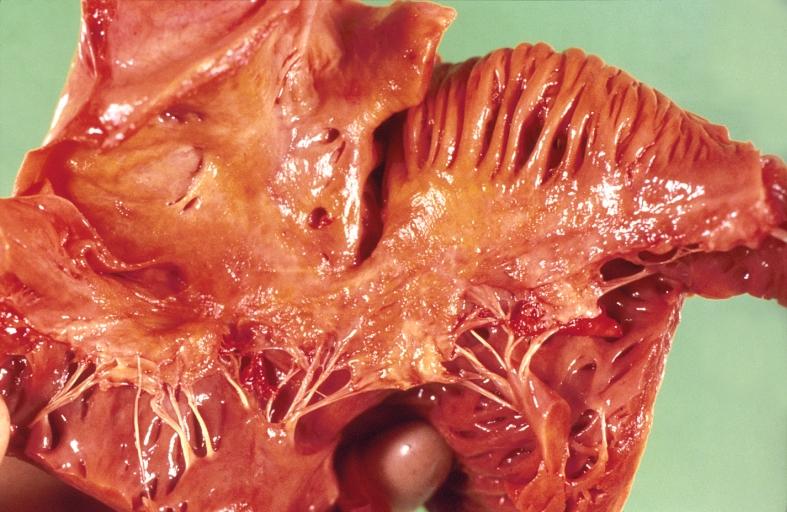

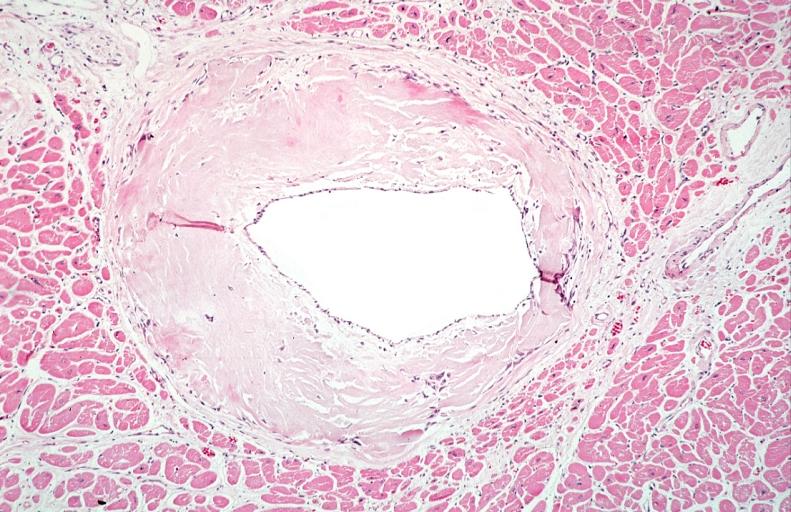

Gross Pathology

The cardiac amyloid deposits are most commonly seen in the myocardium, but can also be seen in atria, pericardium, endocardium and microvasculature.

- On gross examination, the myocardium is thicker, firm and rubbery in consistency. More than half of myocardium involvement is common in the AL type of cardiac amyloidosis.

- The size of ventricular cavity remains unchanged, however filling of the ventricles is restricted (causing restrictive cardiomyopathy) because of the stiffening of ventricular wall as a result of deposition of amyloid material.

- Pericardial effusion and valvular dysfunction is common from pericardial and endocardial involvement. Intracardiac thrombus formation is frequently seen and may result in fatal thromboembolism [12][13][14]

|

|

|

|

|

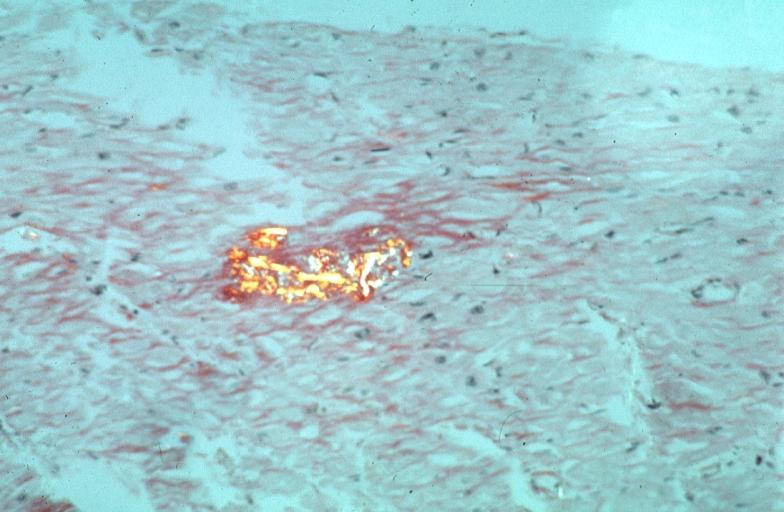

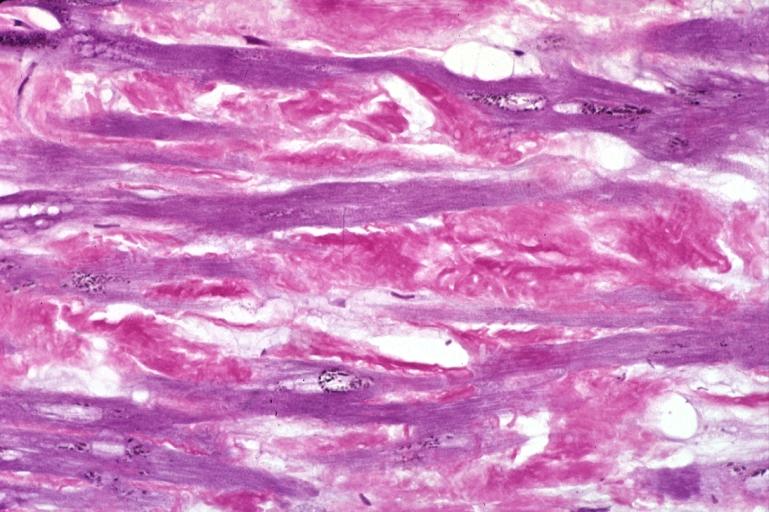

Microscopic Pathology

- On microscope, the intercellular deposits of hyaline like amyloid material is evident. Resultant myocardial fibrosis restricts the movement of the ventricle, compromising complete filling of the ventricle during diastole.

- Amyloid deposits are also seen in the vasculature, particularly the microvasculature thereby sparing the large epicardial vessels. This leads to myocardial ischemia and tissue infarction.

|

|

|

References

- ↑ Dharmarajan K, Maurer MS (2012). "Transthyretin cardiac amyloidoses in older North Americans". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 765–74. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03868.x. PMC 3325376. PMID 22329529. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Merlini G, Bellotti V (2003). "Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (6): 583–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMra023144. PMID 12904524. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Falk RH, Comenzo RL, Skinner M (1997). "The systemic amyloidoses". The New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (13): 898–909. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709253371306. PMID 9302305. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A (1999). "Amyloidosis: recognition, confirmation, prognosis, and therapy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 74 (5): 490–4. doi:10.4065/74.5.490. PMID 10319082. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Banypersad SM, Moon JC, Whelan C, Hawkins PN, Wechalekar AD (2012). "Updates in cardiac amyloidosis: a review". Journal of the American Heart Association. 1 (2): e000364. doi:10.1161/JAHA.111.000364. PMC 3487372. PMID 23130126. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Ng B, Connors LH, Davidoff R, Skinner M, Falk RH (2005). "Senile systemic amyloidosis presenting with heart failure: a comparison with light chain-associated amyloidosis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (12): 1425–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.12.1425. PMID 15983293. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hodkinson HM, Pomerance A (1977). "The clinical significance of senile cardiac amyloidosis: a prospective clinico-pathological study". The Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 46 (183): 381–7. PMID 918253. Retrieved 2012-02-13. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Lie JT, Hammond PI (1988). "Pathology of the senescent heart: anatomic observations on 237 autopsy studies of patients 90 to 105 years old". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 63 (6): 552–64. PMID 3374172. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Tanskanen M, Peuralinna T, Polvikoski T; et al. (2008). "Senile systemic amyloidosis affects 25% of the very aged and associates with genetic variation in alpha2-macroglobulin and tau: a population-based autopsy study". Annals of Medicine. 40 (3): 232–9. doi:10.1080/07853890701842988. PMID 18382889.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Röcken C, Peters B, Juenemann G; et al. (2002). "Atrial amyloidosis: an arrhythmogenic substrate for persistent atrial fibrillation". Circulation. 106 (16): 2091–7. PMID 12379579. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Millucci L, Ghezzi L, Bernardini G, Braconi D, Tanganelli P, Santucci A (2012). "Prevalence of isolated atrial amyloidosis in young patients affected by congestive heart failure". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012: 293863. doi:10.1100/2012/293863. PMC 3317626. PMID 22536133.

- ↑ Nakagawa M, Tojo K, Sekijima Y, Yamazaki KH, Ikeda S (2012). "Arterial thromboembolism in senile systemic amyloidosis: report of two cases". Amyloid : the International Journal of Experimental and Clinical Investigation : the Official Journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis. 19 (2): 118–21. doi:10.3109/13506129.2012.685131. PMID 22583098. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Van de Veire NR, Dierick J, De Sutter J (2012). "Intracardiac emboli as first presentation of cardiac AL amyloidosis". European Heart Journal. 33 (7): 818. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr330. PMC 3345559. PMID 21893485. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Feng D, Edwards WD, Oh JK; et al. (2007). "Intracardiac thrombosis and embolism in patients with cardiac amyloidosis". Circulation. 116 (21): 2420–6. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.697763. PMID 17984380. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)