Alcohol withdrawal

For patient information, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aditya Govindavarjhulla, M.B.B.S. [2]

Overview

Alcohol withdrawal refers to symptoms that can occur when a person who has been drinking alcohol every day suddenly stops drinking alcohol.

Pathophysiology

- Prolonged exposure to alcohol results in inhibition of the inhibitory GABA A-type and NMDA-type glutamate receptors located in the CNS. Without the alcohol, greater CNS excitability results, due to lack of inhibition on the CNS inhibitory receptors by alcohol.

- Elevated norepinephrine has been found in the CSF patients in acute alcohol withdrawal. It is postulated that there is a decreased amount of alpha 2-receptors, resulting in less inhibition of presynaptic norepinephrine release.

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Alcohol abuse or dependence afflicts up to 15 million persons in the United States. It accounts for 100,000 deaths and an economic burden of over 100 billion dollars per year. The lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is approximately 14% and of alcohol dependence is 8%. Approximately 500,000 patients/year develop withdrawal that is severe enough to prompt pharmacologic management.

- Between 13% and 71% of persons admitted for alcohol detoxification have evidence of withdrawal.

- Approximately 3% of chronic alcoholics develop withdrawal seizures. Five percent of patients with alcohol withdrawal develop delirium tremens (DTs), which is associated with a mortality of approximately 5%.

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

How well a person does depends on the amount of organ damage and whether the person can stop drinking completely. Alcohol withdrawal may range from a mild and uncomfortable disorder to a serious, life-threatening condition. People who continue to drink a lot may develop health problems such as liver and heart disease. Most people who go through alcohol withdrawal make a full recovery. However, death is possible, especially if delirium tremens occurs.

Diagnosis

Criteria

- History of cessation or reduction in heavy and prolonged alcohol use.

- 2 or more of:

- Autonomic hypereactivity

- Hand tremor

- Insomnia

- Nausea and vomiting

- Visual or auditory hallucinations

- Psychomotor agitation

- Anxiety

- Grand mal seizures

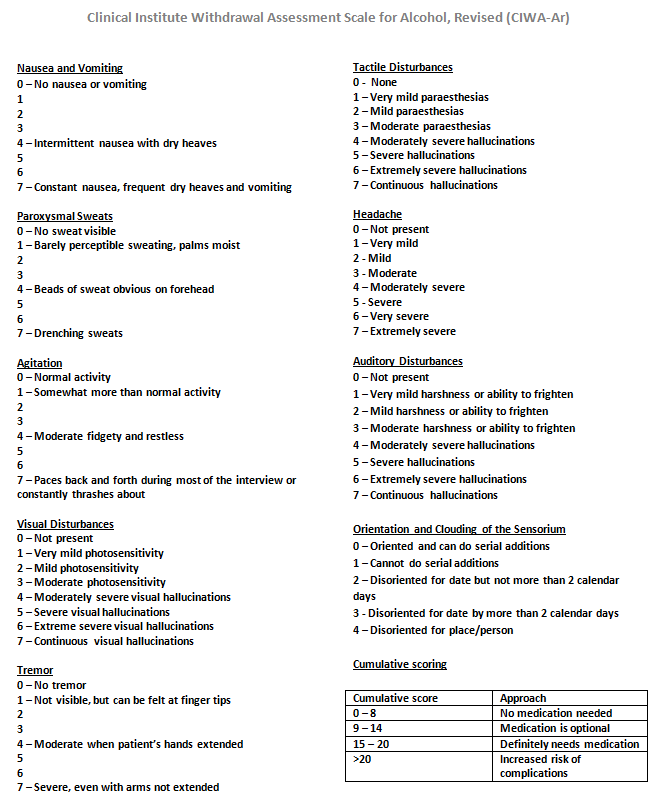

Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol revised (CIWA-Ar)

The CIWA (Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment)[1] is a common measure used in North American hospitals to assess and treat alcohol withdrawal syndrome and for alcohol detoxification. This clinical tool assesses 10 common withdrawal signs.[2] A score of more than 15 points is associated with increased risk of alcohol withdrawal effects such as confusion or seizures.

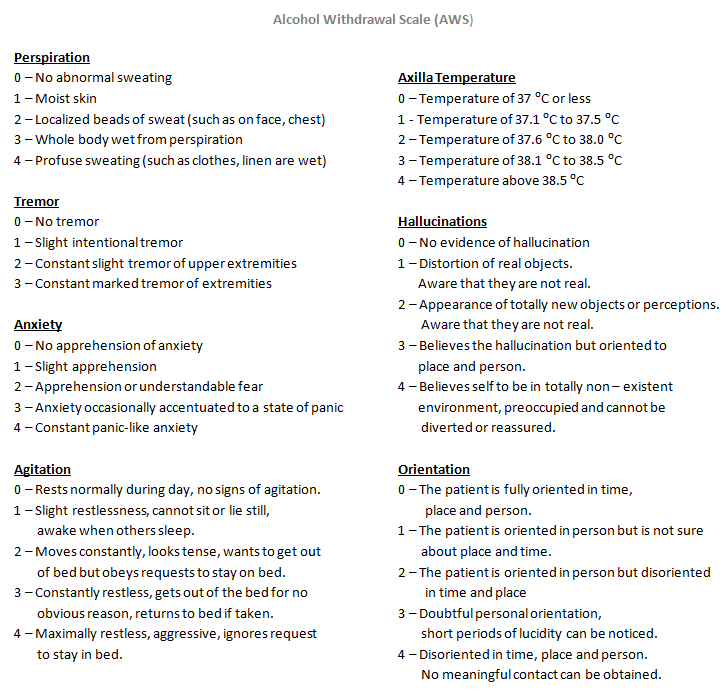

Other Assessment Scales

- Alcohol Assessment Scale

Level of Evidence

| Assessment Scale | Level of Evidence |

| The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) | I |

| Alcohol Assessment Scale (AWS) | IV |

Symptoms

- Common symptoms include:

- Anxiety or nervousness

- Depression

- Not thinking clearly

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Jumpiness or shakiness

- Mood swings

- Nightmares

- Other symptoms may include:

- Clammy skin

- Enlarged (dilated) pupils

- Headache

- Insomnia (sleeping difficulty)

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pallor

- Rapid heart rate

- Sweating

- Tremor of the hands or other body parts

- A severe form of alcohol withdrawal called Delirium tremens can cause:

- Agitation

- Confusion

- Seeing or feeling things that aren't there (Hallucination)

- Fever

- Seizures

Physical examination

- Abnormal eye movements

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Not enough fluids in the body (dehydration)

- Rapid breathing

- Rapid heart rate

- Shaky hands

- Blood and urine tests, including a toxicology screen

Treatment

- No clinical findings can reliably predict who will or will not develop withdrawal. Risk factors for DTs: Previous DTs or detoxifications, Age >30, high degree of alcohol dependence, duration of abuse, the presence of moderate symptoms (CIWA >14) left untreated and concurrent medical illness are all strongly predictive. These findings should prompt intervention. Time abstinent may be a helpful negative predictor. In one large study, patients who were asymptomatic 36 hours after their last drink did not develop symptoms.

- All patients with alcohol abuse should receive 1mg folate QD, magnesium/ phosphate/potassium/fluid volume repletion and thiamine 100 mg IV/IM x1 then 100 mg QD.

- Treatment of alcohol related seizures is on an as needed basis with benzodiazepines. They tend to be transient phenomenon. phenytoin is ineffective in the management of withdrawal seizures, but may be indicated if another seizure disorder or status epilepticus is present. Long term medical suppression or prophylaxis is not indicated for withdrawal seizures. Neuroleptics lower the seizure threshold and should not be used in these patients; however, haloperidol has been used safely in conjunction with benzodiazepines (BDZs).

- BDZs are the cornerstone of therapy for minor withdrawal, seizures and DTs. Fixed schedule therapy, front loading therapy and symptom-triggered therapy have all been evaluated with similar efficacy. Symptoms triggered therapy was associated with less total administration of drug and shorter length of stay but has only been evaluated in patients without acute comorbid illness or seizures and should be restricted to only this limited group of patients.

- In the medically stable patient with no liver dysfunction 10 mg PO/IV is administered every hour till CIWA <10 or sedated. If the patient is stable but has liver disease, give 2 mg lorazepam IV/PO Q 1H till CIWA <10 or sedated. Calculate the total dose used and give this Q6H for 24 hrs. Use that latter regimen for the unstable patient.

- If CIWA is stable x24 hours then decrease the dose by 20%/day. If there is a history of DTs or seizures or the patient is unstable decrease the dose by 10%/day. Give parentral doses of lorazepam recurrence of withdrawal (CIWA >10).

Supportive Care

Goal - Correction of associated disorders, their treatment, providing support for early recovery and prevention of complications.

- Vital signs have to be corrected first.

- Heart rate should be controlled.

- Blood pressure should be maintained using fluids and anti hypertensive medication.

- Identification of comorbid conditions and their treatment.

- A few patients may be dehydrated and they may require intravenous fluid replacement.

- Care has to be taken to avoid fluid overload which can lead to heart failure or exacerbate underlying heart conditions.

- Chronic alcoholics are depleted in reserves of certain electrolytes like magnesium, phosphate. Care has to be provided in correcting them as they play an important role in body metabolism.[3] Administration of magnesium may improve the overall outcome of the patient.

- Alcoholics are vitamin deficient owing to poor dietary habits. Thiamine and folic acid are of major concern.[4]

Inpatient v/s Outpatient

Treatment to alcohol withdrawal patients can be provided in outpatient and inpatient setup.

- Outpatient

- Criteria

- If there are no signs of severe alcohol withdrawal.

- If there is no previous history of alcohol withdrawal.

- If there is a supportive family for the patient.

- If there is no associated comorbid conditions.

- Potential considerations

- Patients may be non-complaint to medication.

- May resolve back to his drinking habits.

- Inpatient

- Criteria

- Severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

- History of alcohol withdrawal symptoms on treatment with outpatient basis.

- Presence of any other comorbid condition or psychiatric condition.

- Non supportive family

- Potential considerations

- Cost of inpatient facilities

Nonpharmacological Treatment

- Providing patient a quiet environment.

- Providing reassurance.

- Motivation for alcohol abstinence.

Pharmacological Treatment

- Benzodiazeipines

- Anticonvulsants

- Anticonvulsants like carbamazepine are of low significance in case of seizures due to alcohol withdrawal.

- They can be used if seizures are not controlled by benzodiazepines(diazepam).

- If a patient suffers two or more alcohol withdrawal seizures or develops status epilepticus, it should be assumed that the seizures are not a result of alcohol withdrawal and should be investigated.

- Anti psychotics

- Anti-psychotic medication should only be made available to patients experiencing hallucinations where benzodiazepines are not effective.

- The patient should also be monitored carefully for hypotension.

- Baclofen

- With the use of baclofen whcih acts upon the GABA-B receptors , doses of diazepam can be reduced.[7]

- It can be used in alcohol addicts.

- Clonidine

- It acts upon the alpha 2 receptors is useful in controlling the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal by reducing the adrenergic surge.

- Clonidine and dexmedetomidine can be used as adjunctive treatment to benzodiazepines.[8]

Withdrawal Regimes

- Symptom triggered therapy

- In this regime patients CIWA-Ar score is evaluated hourly or bi-hourly and depending upon the score the treatment is administered.

- Benzodiazepines are used in the treatment

- It limits the use of excessive medication.

- This approach is cost effective and prevent complications.

- Fixed schedule therapy

- Fixed dosage of drug is given at scheduled intervals

- Can be used if patient is not in severe withdrawal

- Loading dose therapy

- It is used in patients who have experienced seizures during past alcohol withdrawal.

- In this regime doses are tailored for the patient's condition.

Treatment of Complications

- Delirium tremens - benzodiazepines, antipsychotics are used for the treatment.

- Wernicke-Korsakoff’s syndrome - thiamine adminstration

- Covulsions- benzodiazepines are useful, if they are repetitive or status epilepticus develops other causes have to be investigated.

- Failure to manage the alcohol withdrawal syndrome appropriately can lead to permanent brain damage or death.

- It can be prevented by the administration of NMDA antagonists. The NMDA antagonist acamprosate reduces excessive glutamate causing the symptoms. [10]

Treatment in Special Groups

- Pregnancy doesn't increase the risk of alcohol withdrawal.

- Medications used to treat alcohol withdrawal may cause some effect on the fetus.

- Benzodiazepines cause less effects on the fetus and are efficient.

- Hospitalized patients

- Patients hospitalized for some other illness may undergo alcohol withdrawal.

- Early recognition of symptoms of withdrawal is important.

- Early diagnosis and treatment helps in prevention of complications.[11]

Cost Effectiveness

- In all possible cases outpatient detoxification and treatment is most cost effective. [12]

- Outpatient treatment costs $175 to $388 per patientt.

- Inpatient treatment cost $3,319 to $3,665 per patient.

References

- ↑ Puz CA, Stokes SJ (2005). "Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: assessment and treatment with the use of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-revised". Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 17 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2005.04.001. PMID 16115538. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ McKay A, Koranda A, Axen D (2004). "Using a symptom-triggered approach to manage patients in acute alcohol withdrawal". Medsurg Nurs. 13 (1): 15–20, 31, quiz 21. PMID 15029927. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Nutt DJ, Glue P (1990). "Neuropharmacological and clinical aspects of alcohol withdrawal". Annals of Medicine. 22 (4): 275–81. PMID 1979005.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Damsgaard L, Ulrichsen J, Nielsen MK (2010). "[Wernicke's encephalopathy in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms]". Ugeskrift for Laeger (in Danish). 172 (28): 2054–8. PMID 20615374. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Talbot PA (2011). "Timing of efficacy of thiamine in Wernicke's disease in alcoholics at risk". Journal of Correctional Health Care : the Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. 17 (1): 46–50. doi:10.1177/1078345810385913. PMID 21278319. Retrieved 2012-08-16. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Peppers MP (1996). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal in the elderly and in patients with liver disease". Pharmacotherapy. 16 (1): 49–57. PMID 8700792. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ↑ Lyon JE, Khan RA, Gessert CE, Larson PM, Renier CM (2011). "Treating alcohol withdrawal with oral baclofen: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Journal of Hospital Medicine : an Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 6 (8): 469–74. doi:10.1002/jhm.928. PMID 21990176. Retrieved 2012-08-16. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Muzyk AJ, Fowler JA, Norwood DK, Chilipko A (2011). "Role of α2-agonists in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (5): 649–57. doi:10.1345/aph.1P575. PMID 21521867. Retrieved 2012-08-16. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "www.alcohol.gov.au" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ↑ Hinton DJ, Lee MR, Jacobson TL, Mishra PK, Frye MA, Mrazek DA, Macura SI, Choi DS (2012). "Ethanol withdrawal-induced brain metabolites and the pharmacological effects of acamprosate in mice lacking ENT1". Neuropharmacology. 62 (8): 2480–8. PMID 22616110. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Lohr RH (1995). "Treatment of alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 70 (8): 777–82. PMID 7630218. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Hayashida M, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, O'Brien CP, Purtill JJ, Volpicelli JR, Raphaelson AH, Hall CP (1989). "Comparative effectiveness and costs of inpatient and outpatient detoxification of patients with mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 320 (6): 358–65. doi:10.1056/NEJM198902093200605. PMID 2913493. Retrieved 2012-08-16. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)