Whipworm infection pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Microscopic Pathology=== | ===Microscopic Pathology=== | ||

*Microscopy of the colonic [[mucosal]] [[biopsy]] from the affected site will demonstrate [[ | *Microscopy of the colonic [[mucosal]] [[biopsy]] from the affected site will demonstrate infiltration by [[eosinophils]] and [[neutrophils]].<ref name="pmid12236416">{{cite journal| author=Kaur G, Raj SM, Naing NN| title=Trichuriasis: localized inflammatory responses in the colon. | journal=Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health | year= 2002 | volume= 33 | issue= 2 | pages= 224-8 | pmid=12236416 | doi= | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=12236416 }} </ref> | ||

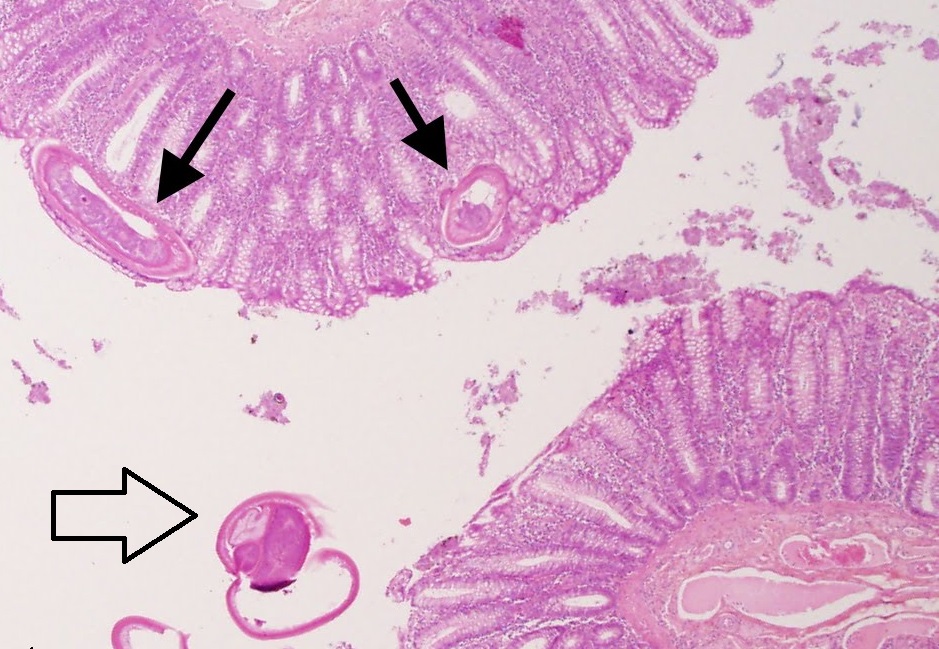

*[[Hematoxylin and eosin stain|Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain]] of an infected [[Colon (anatomy)|colon]] may show one end of the worm embedded in the [[Hyperemic flow|hyperemic]] [[Mucous membrane|mucosa]] and other end freely movable within the [[Lumen (anatomy)|lumen]].<ref name="pmid19724702">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ok KS, Kim YS, Song JH, Lee JH, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Moon JS, Whang DH, Lee HK |title=Trichuris trichiura infection diagnosed by colonoscopy: case reports and review of literature |journal=Korean J. Parasitol. |volume=47 |issue=3 |pages=275–80 |year=2009 |pmid=19724702 |pmc=2735694 |doi=10.3347/kjp.2009.47.3.275 |url=}}</ref> | *[[Hematoxylin and eosin stain|Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain]] of an infected [[Colon (anatomy)|colon]] may show one end of the worm embedded in the [[Hyperemic flow|hyperemic]] [[Mucous membrane|mucosa]] and other end freely movable within the [[Lumen (anatomy)|lumen]].<ref name="pmid19724702">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ok KS, Kim YS, Song JH, Lee JH, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Moon JS, Whang DH, Lee HK |title=Trichuris trichiura infection diagnosed by colonoscopy: case reports and review of literature |journal=Korean J. Parasitol. |volume=47 |issue=3 |pages=275–80 |year=2009 |pmid=19724702 |pmc=2735694 |doi=10.3347/kjp.2009.47.3.275 |url=}}</ref> | ||

[[Image:Tri_worm.jpg|200px|align right|Black arrows showing worm embeded in mucosa of colon and white arrow showing one end of worm in lumen]] | [[Image:Tri_worm.jpg|200px|align right|Black arrows showing worm embeded in mucosa of colon and white arrow showing one end of worm in lumen]] | ||

Revision as of 19:49, 26 July 2017

|

Whipworm infection Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Whipworm infection pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Whipworm infection pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Whipworm infection pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Usama Talib, BSc, MD [2], Syed Hassan A. Kazmi BSc, MD [3]

Overview

Infection is acquired by the ingestion of embryonated eggs from contaminated drinking water and food. Once the eggs are ingested, they hatch in the small intestine then, larvae enter the intestinal crypts. The larvae migrate to the proximal colon and mature into adult worms. The females begin to oviposit 60 to 70 days after infection and shed between 3,000 and 20,000 eggs per day. Whipworm causes disease by colonic mucosal invasion by the adult worms and resulting in inflammation of the colonic mucosa.

Pathophysiology

Life Cycle

1. The eggs develop into a 2-cell stage.

2. The two cell stage then leads to an advanced cleavage stage.

3. The eggs embryonate.

4. Eggs become infective in 15 to 30 days.

5. Mature adult worms travel in the colon.

6. The adult worms (approximately 4 cm in length) live in the cecum and ascending colon. The life span of the adult worm is approximately 1 year.

Transmission

- Whipworm infection is acquired by the ingestion of embryonated eggs from contaminated drinking water and food.

Pathogenesis

- The eggs once ingested hatch in the small intestine, and the larvae enter the intestinal crypts.[1][2]

- The larve migrate to the proximal colon and mature into adult worms.

- The adult worms live in the cecum and ascending colon and attach themselves to the colonic mucosa with the anterior portions threaded into the mucosa.

- The females begin to oviposit 60 to 70 days after infection and shed between 3,000 and 20,000 eggs per day.

- Whipworm causes disease by colonic mucosal invasion of the adult worms and resulting in inflammation of the colonic mucosa.[3]

Associated Conditions

- Whipworm infection is frequently present in combination with Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworm and Entamoeba histolytica infections.

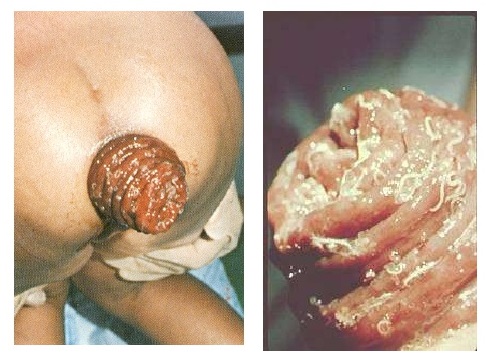

Gross Pathology

- Whipworm infection in humans can lead to rectal prolapse which may be visible grossly.[4]

Microscopic Pathology

- Microscopy of the colonic mucosal biopsy from the affected site will demonstrate infiltration by eosinophils and neutrophils.[5]

- Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of an infected colon may show one end of the worm embedded in the hyperemic mucosa and other end freely movable within the lumen.[6]

References

- ↑ Elston DM (2006). "What's eating you? Trichuris trichiura (human whipworm)". Cutis. 77 (2): 75–6. PMID 16570666.

- ↑ Elsayed S, Yilmaz A, Hershfield N (2004). "Trichuris trichiura worm infection". Gastrointest Endosc. 60 (6): 990–1. PMID 15605023.

- ↑ Tilney LG, Connelly PS, Guild GM, Vranich KA, Artis D (2005). "Adaptation of a nematode parasite to living within the mammalian epithelium". J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 303 (11): 927–45. doi:10.1002/jez.a.214. PMID 16217807.

- ↑ "CDC - Trichuriasis".

- ↑ Kaur G, Raj SM, Naing NN (2002). "Trichuriasis: localized inflammatory responses in the colon". Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 33 (2): 224–8. PMID 12236416.

- ↑ Ok KS, Kim YS, Song JH, Lee JH, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Moon JS, Whang DH, Lee HK (2009). "Trichuris trichiura infection diagnosed by colonoscopy: case reports and review of literature". Korean J. Parasitol. 47 (3): 275–80. doi:10.3347/kjp.2009.47.3.275. PMC 2735694. PMID 19724702.