Ovarian cancer

For patient information click here.

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

|

WikiDoc Resources for Ovarian cancer |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Ovarian cancer Most cited articles on Ovarian cancer |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Ovarian cancer |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Ovarian cancer at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Ovarian cancer Clinical Trials on Ovarian cancer at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Ovarian cancer NICE Guidance on Ovarian cancer

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Ovarian cancer Discussion groups on Ovarian cancer Patient Handouts on Ovarian cancer Directions to Hospitals Treating Ovarian cancer Risk calculators and risk factors for Ovarian cancer

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Ovarian cancer |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Ovarian cancer is a malignant tumor, of any histology, on or within an ovary. Because many ovarian tumors are benign but have the potential to become malignant, a broad definition of ovarian cancer includes all ovarian tumors, malignant and benign.

Epidemiology

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women, the leading cause of death from gynecological malignancy, and the second most commonly diagnosed gynecologic malignancy.[1]

The exact cause is usually unknown. The disease is more common in industrialized nations, with the exception of Japan. In the United States, females have a 1.4% to 2.5% (1 out of 40-60 women) lifetime chance of developing ovarian cancer.

Older women are at highest risk. More than half of the deaths from ovarian cancer occur in women between 55 and 74 years of age and approximately one quarter of ovarian cancer deaths occur in women between 35 and 54 years of age.

The risk of developing ovarian cancer appears to be affected by several factors. The more children a woman has, the lower her risk of ovarian cancer. Early age at first pregnancy, older ages of final pregnancy and the use of low dose hormonal contraception have also been shown to have a protective effect. Ovarian cancer is reduced in women after tubal ligation.

The link to the use of fertility medication, such as Clomiphene citrate, has been controversial. An analysis in 1991 raised the possibility that use of drugs may increase the risk of ovarian cancer. Several cohort studies and case-control studies have been conducted since then without providing conclusive evidence for such a link. [2] It will remain a complex topic to study as the infertile population differs in parity from the "normal" population.

There is good evidence that in some women genetic factors are important. Carriers of certain mutations of the BRCA1 or the BRCA2 gene and certain populations (e.g. Ashkenazi Jewish women) are at a higher risk of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer, often at an earlier age than the general population. Patients with a personal history of breast cancer or a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, especially if at a young age, may have an elevated risk. A strong family history of uterine cancer, colon cancer, or other gastrointestinal cancers may indicate the presence of a syndrome known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, also known as Lynch II syndrome), which confers a higher risk for developing ovarian cancer. Patients with strong genetic risk for ovarian cancer may consider the use of prophylactic i.e. preventative oophorectomy after completion of child-bearing.

A Swedish study, which followed more than 61,000 women for 13 years, has found a significant link between milk consumption and ovarian cancer. According to the BBC, "[Researchers] found that milk had the strongest link with ovarian cancer - those women who drank two or more glasses a day were at double the risk of those who did not consume it at all, or only in small amounts." [3] Recent studies have shown that women in sunnier countries have a lower rate of ovarian cancer, which may have some kind of connection with exposure to Vitamin D.

Other factors that have been investigated, such as talc use, asbestos exposure, high dietary fat content, and childhood mumps infection, are controversial and have not been definitively proven.

"Associations were also found between alcohol consumption and cancers of the ovary and prostate, but only for 50 g and 100 g a day."[4]

Classification

Ovarian cancer is classified according to the histology of the tumor, obtained in a pathology report. Histology dictates many aspects of clinical treatment, management, and prognosis.

- Surface epithelial-stromal tumour, including serous and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, is the most common type of ovarian cancer.

- Sex cord-stromal tumor, including estrogen-producing granulosa cell tumor and virilizing Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor or arrhenoblastoma, accounts for 8% of ovarian cancers.

- Germ cell tumor accounts for approximately 5% of ovarian cancers. It tends to occur in young women and girls, and has a better prognosis than other ovarian tumors.

- mixed tumors, containing elements of more than one tumor histology

Ovarian cancer often is primary, but can also be secondary, the result of metastasis from a primary cancer elsewhere in the body. For example, from breast cancer, or from gastrointestinal cancer (in which case the ovarian cancer is a Krukenberg cancer). Surface epithelial-stromal tumor can originate in the lining of the abdominal cavity, in which case the ovarian cancer is secondary to primary peritoneal cancer, but treatment is basically the same as for primary ovarian cancer of this type.

Symptoms

Studies on the accuracy of symptoms

Two case-control studies, both subject to results being inflated by spectrum bias, have been reported. The first found that women with ovarian cancer had symptoms of increased abdominal size, bloating, urge to pass urine and pelvic pain.[5] The smaller, second study found that women with ovarian cancer had pelvic/abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, and difficulty eating/feeling full.[6] The latter study created a symptom index that was considered positive if any of the 6 symptoms "occurred >12 times per month but were present for <1 year".They reported a sensitivity of 57% for early-stage disease and specificity 87% to 90%.

Ovarian Cancer Symptoms Consensus Statement

In 2007, the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and American Cancer Society originated the following consensus statement regarding the symptoms of ovarian cancer.[7]

Historically ovarian cancer was called the “silent killer” because symptoms were not thought to develop until the chance of cure was poor. However, recent studies have shown this term is untrue and that the following symptoms are much more likely to occur in women with ovarian cancer than women in the general population. These symptoms include:

- Bloating

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

- Urinary symptoms (urgency or frequency)

Women with ovarian cancer report that symptoms are persistent and represent a change from normal for their bodies. The frequency and/or number of such symptoms are key factors in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Several studies show that even early stage ovarian cancer can produce these symptoms. Women who have these symptoms almost daily for more than a few weeks should see their doctor, preferably a gynecologist. Prompt medical evaluation may lead to detection at the earliest possible stage of the disease. Early stage diagnosis is associated with an improved prognosis.

Several other symptoms have been commonly reported by women with ovarian cancer. These symptoms include fatigue, indigestion, back pain, pain with intercourse, constipation and menstrual irregularities. However, these other symptoms are not as useful in identifying ovarian cancer because they are also found in equal frequency in women in the general population who do not have ovarian cancer.

Diagnosis

Ovarian cancer at its early stages(I/II) is difficult to diagnose until it spreads and advances to later stages(III/IV). This is due to the fact that most of the common symptoms are non-specific.

When an ovarian malignancy is included in the list of diagnostic possibilities, a limited number of laboratory tests are indicated. A complete blood count (CBC) and serum electrolyte test should be obtained in all patients.

The serum BHCG level should be measured in any female in whom pregnancy is a possibility. In addition, a serum AFP and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be measured in young girls and adolescents with suspected ovarian tumors because the younger the patient, the greater the likelihood of a malignant germ cell tumor.

The blood test called CA-125 is useful in differential diagnosis and in follow up of the disease, but it has not been shown to be an effective method to screen for early-stage ovarian cancer and is currently not recommended for this use.

Current research is looking at ways to combine tumor markers along with other indicators of disease (i.e. radiology and/or symptoms) to improve accuracy. The challenge in such an approach is that the very low population prevalence of ovarian cancer means that even testing with very high sensitivity and specificity will still lead to unacceptable numbers of false positive results (i.e. performing surgical procedures in which cancer is not found intra-operatively). This is exemplified by the recent discovery of proteomic predictors that showed 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity. [8]

A pelvic examination, including CT scan, trans-vaginal ultrasound, is also of utility. Physical examination may reveal increased abdominal girth and /or ascites (fluid within the abdominal cavity). Pelvic examination may reveal an ovarian or abdominal mass. The pelvic exam can include a rectovaginal component for better palpation of the ovaries. For very young patients, magnetic resonance imaging may be preferred to rectal and vaginal examination.

Staging

Ovarian cancer staging is by the FIGO staging system and uses information obtained after surgery, which can include a total abdominal hysterectomy, removal of (usually) both ovaries and fallopian tubes, (usually) the omentum, and pelvic (peritoneal) washings for cytology. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage is the same as the FIGO stage.

- Stage I - limited to one or both ovaries

- IA - involves one ovary; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

- IB - involves both ovaries; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; negative washings

- IC - tumor limited to ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, positive washings

- Stage II - pelvic extension or implants

- IIA - extension or implants onto uterus or fallopian tube; negative washings

- IIB - extension or implants onto other pelvic structures; negative washings

- IIC - pelvic extension or implants with positive peritoneal washings

- Stage III - microscopic peritoneal implants outside of the pelvis; or limited to the pelvis with extension to the small bowel or omentum

- IIIA - microscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis

- IIIB - macroscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis less than 2 cm in size

- IIIC - peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis > 2 cm or lymph node metastases

- Stage IV - distant metastases--in the liver, or outside the peritoneal cavity

Para-aortic lymph node metastases are considered regional lymph nodes (Stage IIIC).

Treatment

Surgery is the preferred treatment and is frequently necessary to obtain a tissue specimen for differential diagnosis via its histology. Surgery performed by a specialist in gynecologic oncology usually results in an improved result. Improved survival is attributed to more accurate staging of the disease and a higher rate of aggressive surgical excision of tumor in the abdomen by gynecologic oncologists as opposed to general gynecologists and general surgeons.

The type of surgery depends upon how widespread the cancer is when diagnosed (the cancer stage), as well as the presumed type and grade of cancer. The surgeon may remove one (unilateral oophorectomy) or both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy), the fallopian tubes (salpingectomy), and the uterus (hysterectomy). For some very early tumors (stage 1, low grade or low-risk disease), only the involved ovary and fallopian tube will be removed (called a "unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy," USO), especially in young females who wish to preserve their fertility. In advanced malignancy, where complete resection is not feasible, as much tumor as possible is removed (debulking surgery). In cases where this type of surgery is successful (i.e. < 1 cm in diameter of tumor is left behind ["optimal debulking"]), the prognosis is improved compared to patients where large tumor masses (> 1 cm in diameter) are left behind. Minimally invasive surgical techniques may facilitate the safe removal of very large (greater than 10 cm) tumors with fewer complications of surgery.[9]

Chemotherapy is used after surgery to treat any residual disease, if appropriate. This depends on the histology of the tumor; some kinds of tumor (particularly teratoma) are not sensitive to chemotherapy. In some cases, there may be reason to perform chemotherapy first, followed by surgery.

Many oncologists recommend intravenous (IV) chemotherapy including a platinum drug with a taxane as a preferred method of treating advanced ovarian cancer. However, three recent randomized studies clinical trials suggest that chemotherapy that is partly IV and partly via direct infusion into the abdominal cavity (intraperitoneal or IP) may improve median survival time. IP chemotherapy generally has higher toxicity and its advantages are still debated among specialists. Currently for Stage IIIC ovarian adenocarcinomas after optimal debulking, median time for survival is statistically significantly longer for patient receiving intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Patients in this clincial trial did report less compliance with IP chemotherapy, and fewer than half of the patients received all six cycles of IP chemotherapy. Despite this high "drop-out" rate, the group as a whole (including the patients that didn't complete IP chemotherpy treatment) survived longer on average than patients who received intravenous chemotherapy alone. These results can be interpreted in couple of ways. One could argue if the IP chemotherapy treatment group had completed the six cycles of chemotherapy their lives would have been prolonged even longer. Or the advantages of receiving IP chemotherapy are significant in the early phases of chemotherapy. Some specialists believe the IP chemotherapy toxicities will be unnecessary with improved IV chemotherapy drugs currently being developed.

Radiation therapy is not effective for advanced stages because when vital organs are in the radiation field, a high dose cannot be safely delivered.

Prognosis

Ovarian cancer has a poor prognosis. It is disproportionately deadly because symptoms are vague and non-specific, hence diagnosis is late. More than 60% of patients presenting with this cancer already have stage III or stage IV cancer, when it has already spread beyond the ovaries.

Ovarian cancers that are malignant shed cells into the naturally occurring fluid within the abdominal cavity. These cells can implant on other abdominal (peritoneal) structures included the uterus, urinary bladder, bowel, lining of the bowel wall (omentum) and can even spread to the lungs. These cells can begin forming new tumor growths before cancer is even suspected.

More than 50% of women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed in the advanced stages of the disease because no cost-effective screening test for ovarian cancer exists. The five year survival rate for all stages is only 35% to 38%. If, however, diagnosis is made early in the disease, five-year survival rates can reach 90% to 98%.

Germ cell tumors of the ovary have a much better prognosis than other ovarian cancers, in part because they tend to grow rapidly to a very large size, hence they are detected sooner.

Complications

- spread of the cancer to other organs

- progressive function loss of various organs

- ascites (fluid in the abdomen)

- Intestinal obstruction

Pathological Findings

-

In this TAH-BSO specimen, the right ovary (on the left of the image) has been replaced by a solid serous carcinoma. The contralateral ovarian tumor is grossly cystic and could be termed a "cystadenocarcinoma." The patient had omental metastases and positive peritoneal fluid cytology. This cancer, which was discovered at exploratory laparotomy, apparently developed very rapidly; the patient had a normal pelvic ultrasound exam only 2 months before. (Courtesy of Ed Uthman, MD)

-

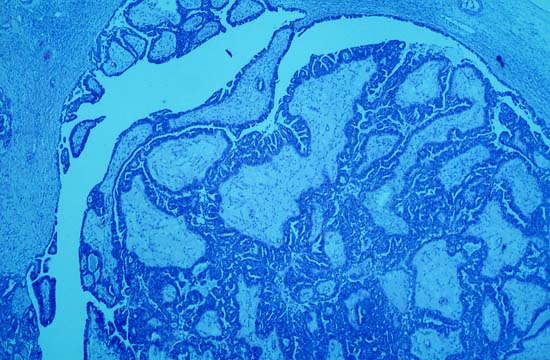

Photomicrograph is from the solid / papillary right ovarian tumor. As shown in this photo, much of the tumor had a papillary pattern with exuberant epithelial proliferation but no obvious stromal invasion. Other areas, such as the one depicted in the second photo, show extensive stromal invasion, the criterion upon which rests the diagnosis of frank malignancy.

-

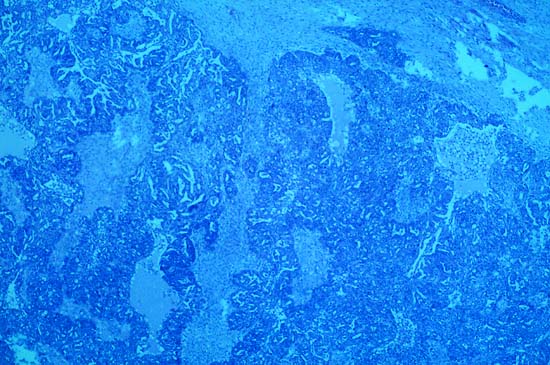

Extensive stromal invasion, the criterion upon which rests the diagnosis of frank malignancy

References

- ↑ The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Section 18. Gynecology And Obstetrics Chapter 241. Gynecologic Neoplasms

- ↑ Brinton LA, Moghissi KS, Scoccia B, Westhoff CL, Lamb EJ (2005). "Ovulation induction and cancer risk". Fertil. Steril. 83 (2): 261–74, quiz 525-6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.09.016. PMID 15705362.

- ↑ BBC News Milk link to ovarian cancer risk 29 November 2004

- ↑ Alcohol consumption and cancer risk

- ↑ Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG (2004). "Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics". JAMA. 291 (22): 2705–12. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2705. PMID 15187051.

- ↑ Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW; et al. (2007). "Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection". Cancer. 109 (2): 221–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.22371. PMID 17154394.

- ↑ "Ovarian Cancer Symptoms Consensus Statement" (pdf). Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ↑ Petricoin EF, Ardekani AM, Hitt BA; et al. (2002). "Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer". Lancet. 359 (9306): 572–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07746-2. PMID 11867112.

- ↑ Ehrlich PF, Teitelbaum DH, Hirschl RB, Rescorla F (2007). "Excision of large cystic ovarian tumors: combining minimal invasive surgery techniques and cancer surgery--the best of both worlds". J. Pediatr. Surg. 42 (5): 890–3. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.069. PMID 17502206.

See also

- List of notable women who have battled ovarian cancer

- Germ cell tumor

- Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

- Ovarian cyst

External links

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: Ovarian cancer

- OVARIAN CANCER RESEARCH FOUNDATION www.ocrf.com.au

- "How to tell if an Ovarian Mass is Malignant?"

- Schrecengost A. "Ovarian mass--benign or malignant?" AORN J. 2002 Nov;76(5):792-802, 805-6; quiz 807-10. PMID 12463079 Article

- Information about ovarian cancer,treatment and cure

- Ovarian cancer forum - a fellowship among survivors, caregivers, supporters to promote OVCA awareness and fund for research

- Historical account of 24-year-old girl's battle with ovarian cancer

- Ovarian Cancer Action site, which funds awareness and research into early detection

- Ovarian Cancer Institute, a research-based organization dedicated to finding an early detection test for ovarian cancer

- Wyllie O Hagan site for artists who use their work to raise international awareness of ovarian cancer missions

- The Johns Hopkins Ovarian Cancer Web Site

- The Ovarian Cancer National Alliance, a National organization uniting ovarian cancer activists, advocates and health care professionals working towards increasing public and professional understanding of ovarian cancer

- US National Institutes of Health - High quality, peer-reviewed medical information. The source of the PDQs, a must read for all cancer patients interested in technical literature

- Template:MedlinePlusOverview

- Template:MerckManual

- Ovarian mailing list - A very active and helpful mailing list for 1200+ ovarian cancer patients

- Ovarian Cancer Canada

- MOCA - Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance

- Ovarian Cancer blog by a woman with Stage 3c ovarian cancer

- NOCA - National Ovarian Cancer Association (Canada)

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Ovacome - ovarian cancer support and information network (UK)

- Ovarian Register - UK register of families affected by ovarian cancer (Cambridge, UK)

- The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund

- Diary of a woman's fight against ovarian cancer including links to many helpful resources

- Teal Talk - online ovarian cancer community providing a message board and chat room for sharing information, inspiration, and support

- Chicago Ovarian Cancer Alliance - a Chicago-based resource and advocacy group

- Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

- MedHelp Ovarian Cancer Forum - an online health forum where questions are fielded by Mass General Hospital and other members

- The Official Patient's Sourcebook on Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Template:Tumors Template:Epithelial neoplasms Template:SIB

ar:سرطان المبيض de:Ovarialkarzinom fy:Aaistokkanker nl:Ovariumcarcinoom no:Eggstokkreft fi:Munasarjasyöpä