Cystic fibrosis

For patient information click here

| Cystic fibrosis | |

| |

|---|---|

| Lung: Gross; Cystic fibrosis Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | E84 |

| ICD-9 | 277 |

| OMIM | 219700 |

| DiseasesDB | 3347 |

| MedlinePlus | 000107 |

| MeSH | D003550 |

|

Cystic fibrosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cystic fibrosis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cystic fibrosis |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

Historical Perspective

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology & Demographics

Risk Factors

Screening

Causes

Differentiating Cystic fibrosis

Complications & Prognosis

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms | Physical Examination | Staging | Laboratory tests | Electrocardiogram | X Rays | CT | MRI Echocardiography or Ultrasound | Other images | Alternative diagnostics

Treatment

Medical therapy | Surgical options | Primary prevention | Secondary prevention | Financial costs | Future therapies

Diagnosis and monitoring

Cystic fibrosis may be diagnosed by many different categories of testing including those such as, newborn screening, sweat testing, or genetic testing. As of 2006 in the United States, 10 percent of cases are diagnosed shortly after birth as part of newborn screening programs. The newborn screen initially measures for raised blood concentration of immunoreactive trypsinogen.[1] However, most states and countries do not screen for CF routinely at birth. Therefore, most individuals are diagnosed after symptoms prompt an evaluation for cystic fibrosis. The most commonly-used form of testing is the sweat test. Sweat-testing involves application of a medication that stimulates sweating (pilocarpine) to one electrode of an apparatus and running electric current to a separate electrode on the skin. This process, called iontophoresis, causes sweating; the sweat is then collected on filter paper or in a capillary tube and analyzed for abnormal amounts of sodium and chloride. People with CF have increased amounts of sodium and chloride in their sweat. CF can also be diagnosed by identification of mutations in the CFTR gene.[2]

A multitude of tests is used to identify complications of CF and to monitor disease progression. X-rays and CAT scans are used to examine the lungs for signs of damage or infection. Examination of the sputum under a microscope is used to identify which bacteria are causing infection so that effective antibiotics can be given. Pulmonary function tests measure how well the lungs are functioning, and are used to measure the need for and response to antibiotic therapy. Blood tests can identify liver problems, vitamin deficiencies, and the onset of diabetes. DEXA scans can screen for osteoporosis and testing for fecal elastase can help diagnose insufficient digestive enzymes.

Prenatal diagnosis

Couples who are pregnant or who are planning a pregnancy can themselves be tested for CFTR gene mutations to determine the likelihood that their child will be born with cystic fibrosis. Testing is typically performed first on one or both parents and, if the risk of CF is found to be high, testing on the fetus can then be performed. Cystic fibrosis testing is offered to many couples in the US.[3] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends testing for couples who have a personal or close family history. Additionally, ACOG recommends that carrier testing be offered to all Caucasian couples and be made available to couples of other ethnic backgrounds.[4]

Because development of CF in the fetus requires each parent to pass on a mutated copy of the CFTR gene and because CF testing is expensive, testing is often performed on just one parent initially. If that parent is found to be a carrier of a CFTR gene mutation, the other parent is then tested to calculate the risk that their children will have CF. CF can result from more than a thousand different mutations and, as of 2006, it is not possible to test for each one. Testing analyzes the blood for the most common mutations such as ΔF508 — most commercially available tests look for 32 or fewer different mutations. If a family has a known uncommon mutation, specific screening for that mutation can be performed. Because not all known mutations are found on current tests, a negative screen does not guarantee that a child will not have CF.[5] In addition, because the mutations tested are necessarily those most common in the highest risk groups, testing in lower risk ethnicities is less successful because the mutations commonly seen in these groups are less common in the general population. These couples may therefore consider testing through labs that offer CF screens with a high number of mutations tested.

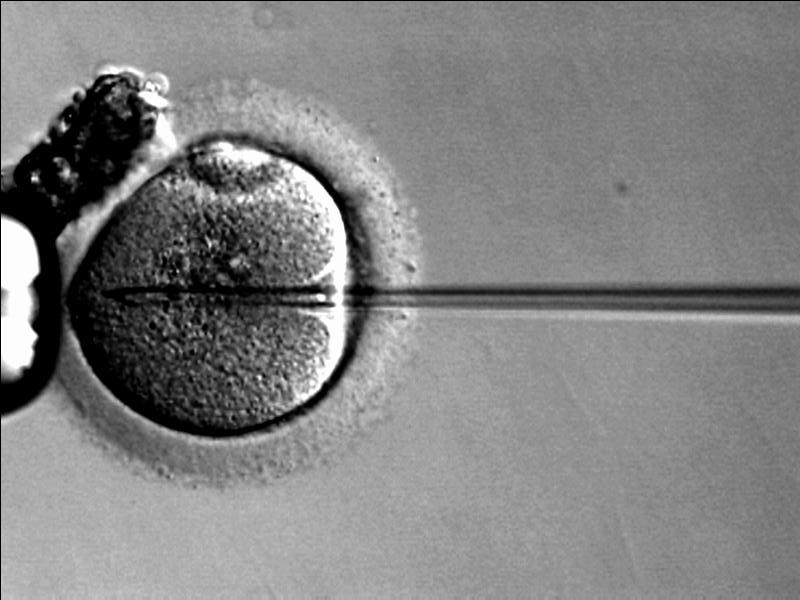

Couples who are at high risk for having a child with CF will often opt to perform further testing before or during pregnancy. In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic diagnosis offers the possibility to examine the embryo prior to its placement into the uterus. The test, performed 3 days after fertilization, looks for the presence of abnormal CF genes. If two mutated CFTR genes are identified, the embryo is not used for embryo transfer and an embryo with at least one normal gene is implanted.

During pregnancy, testing can be performed on the placenta (chorionic villus sampling) or the fluid around the fetus (amniocentesis). However, chorionic villus sampling has a risk of fetal death of 1 in 100 and amniocentesis of 1 in 200,[6] so the benefits must be determined to outweigh these risks prior to going forward with testing. Alternatively, some couples choose to undergo third party reproduction with egg or sperm donors.

The role of chronic infection in lung disease

The lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis are colonized and infected by bacteria from an early age. These bacteria, which often spread amongst individuals with CF, thrive in the altered mucus, which collects in the small airways of the lungs. This mucus encourages the development of bacterial microenvironments (biofilms) that are difficult for immune cells (and antibiotics) to penetrate. The lungs respond to repeated damage by thick secretions and chronic infections by gradually remodeling the lower airways (bronchiectasis), making infection even more difficult to eradicate.[7]

Over time, both the types of bacteria and their individual characteristics change in individuals with CF. In the initial stage, common bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Hemophilus influenzae colonize and infect the lungs. Eventually, however, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (and sometimes Burkholderia cepacia) dominates. Once within the lungs, these bacteria adapt to the environment and develop resistance to commonly used antibiotics. Pseudomonas can develop special characteristics that allow the formation of large colonies, known as "mucoid" Pseudomonas and rarely seen in people that do not have CF.[7]

One way in which infection has spread is by passage between different individuals with CF.[8] In the past, people with CF often participated in summer "CF Camps" and other recreational gatherings.[9][10] Hospitals grouped patients with CF into common areas and routine equipment (such as nebulizers)[11] was not sterilized between individual patients.[12] This led to transmission of more dangerous strains of bacteria among groups of patients. As a result, individuals with CF are routinely isolated from one another in the healthcare setting and healthcare providers are encouraged to wear gowns and gloves when examining patients with CF in order to limit the spread of virulent bacterial strains.[13] Often, patients with particularly damaging bacteria will attend clinics on different days and in different buildings than those without these infections.

Molecular biology

The CFTR gene is found at the q31.2 locus of chromosome 7, is 230 000 base pairs long, and creates a protein that is 1,480 amino acids long. The most common mutation, ΔF508 is a deletion (Δ) of three nucleotides that results in a loss of the amino acid phenylalanine (F) at the 508th (508) position on the protein. This mutation accounts for seventy percent of CF worldwide and 90 percent of cases in the United States. There are over 1,400 other mutations that can produce CF, however. In Caucasian populations, the frequency of mutations is as follows:[14]Template:Entête tableau charte alignement

! Mutation

! Frequency

worldwide

|-----

| ΔF508

| 66.0%

|-Template:Ligne grise

| G542X

| 2.4%

|-----

| G551D

| 1.6%

|-Template:Ligne grise

| N1303K

| 1.3%

|-----

| W1282X

| 1.2%

|}

There are several mechanisms by which these mutations cause problems with the CFTR protein. ΔF508, for instance, creates a protein that does not fold normally and is degraded by the cell. Several mutations, which are common in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, result in proteins that are too short because production is ended prematurely. Less common mutations produce proteins that do not use energy normally, do not allow chloride to cross the membrane appropriately, or are degraded at a faster rate than normal. Mutations may also lead to fewer copies of the CFTR protein being produced.[15]

Structurally, CFTR is a type of gene known as an ABC gene.[15] Its protein possesses two ATP-hydrolyzing domains which allows the protein to use energy in the form of ATP. It also contains two domains comprised of 6 alpha helices apiece, which allow the protein to cross the cell membrane. A regulatory binding site on the protein allows activation by phosphorylation, mainly by cAMP-dependent protein kinase.[15] The carboxyl terminal of the protein is anchored to the cytoskeleton by a PDZ domain interaction.[16]

Pathological Findings: A Case Example

Clinical Summary

A female infant was the product of an uncomplicated term delivery, though meconium staining was noted at birth. During the first day post-partum, the infant's abdomen became progressively distended and a meconium ileus was suspected. Surgery confirmed the presence of a meconium ileus and a section of perforated atretic jejunum proximal to the ileus was resected. Eight days later, the patient's condition had deteriorated. A second operation revealed a segment of necrotic bowel, which was removed. Subsequently the infant's pulmonary function deteriorated and she required frequent suctioning. She developed repeated episodes of pneumonia (E. coli and Pseudomonas grew out on cultures) complicated by atelectasis secondary to pneumothorax. The patient died at 25-days-of-age in respiratory failure.

Autopsy Findings

Bilateral, extensive organizing bronchopneumonia was present with evidence of a pneumothorax and atelectasis. There were significant changes in the pancreas consistent with cystic fibrosis as well as involvement of the small intestine and changes related to the surgical procedures.

-

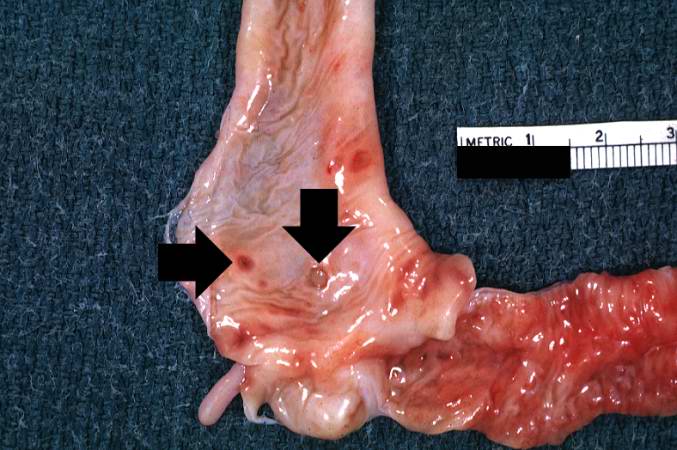

A gross photograph of liver and pancreas from the autopsy. The pancreas is slightly smaller than normal and it has a mucous consistency.

-

This section of duodenum demonstrates dilation, loss of rugae, and areas of ulceration (arrows).

-

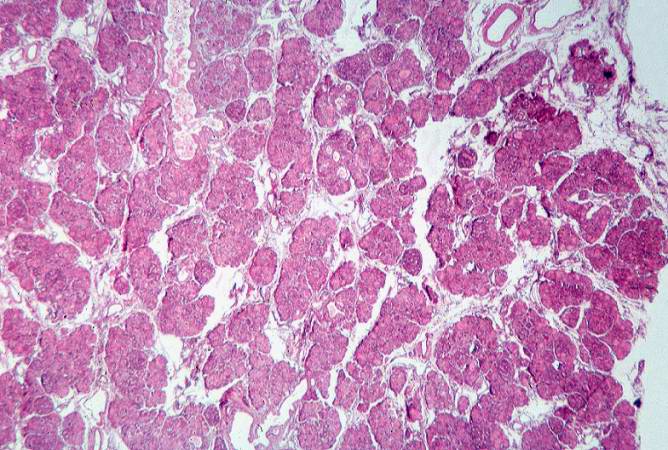

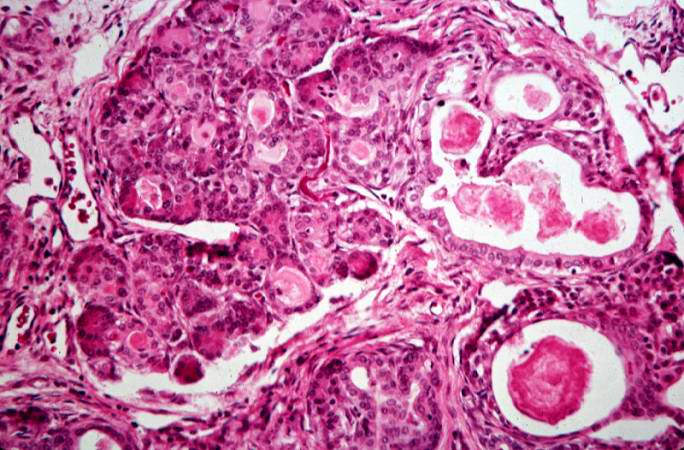

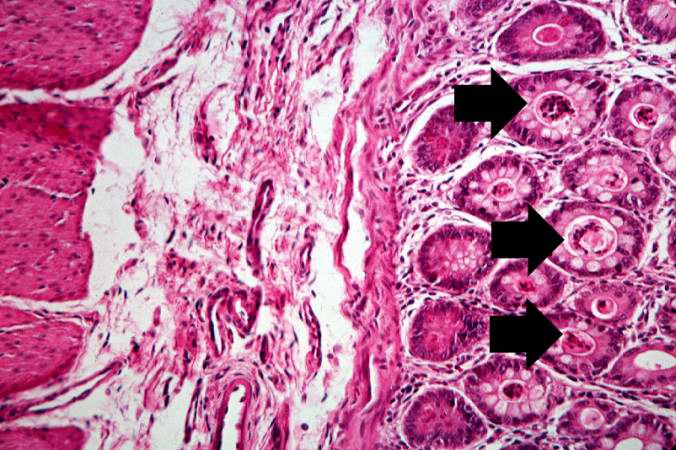

This low-power photomicrograph of pancreas shows increased interstitial connective tissue resulting in accentuation of the lobular pattern.

-

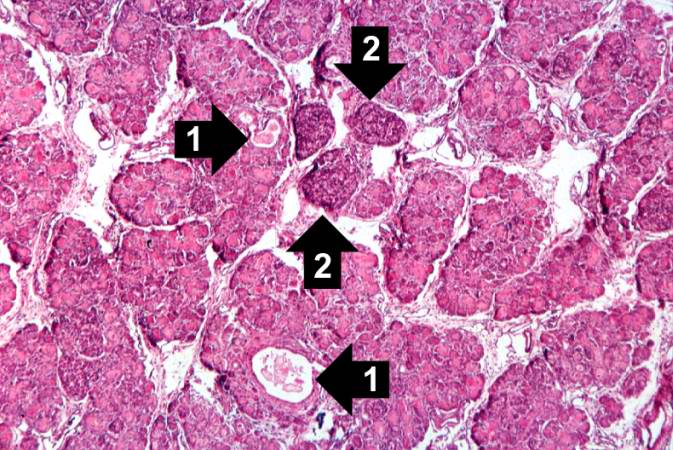

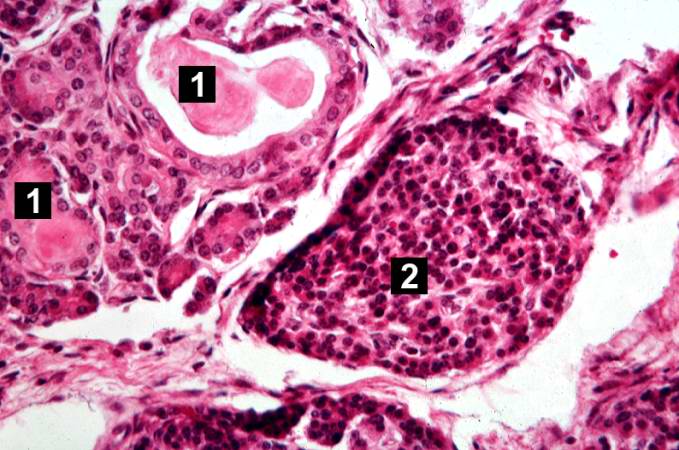

This higher-power photomicrograph of the pancreas shows interstitial tissue and the presence of small cystic spaces (1) within the acinar lobules. These spaces are filled with an eosinophilic proteinaceous material. The islets of Langerhans (2) are unaffected.

-

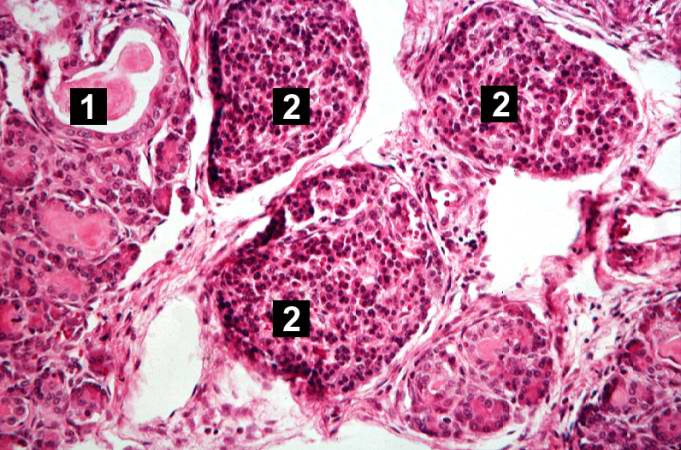

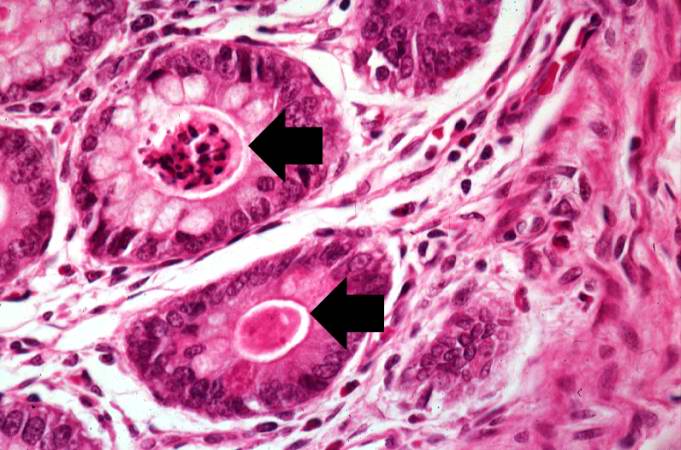

This higher-power photomicrograph shows a cystic space (1) within an acinar lobule. Islets of Langerhans (2) are also visible.

-

This high-power photomicrograph shows more clearly these variably-sized cystic spaces within the acinar pancreas.

-

This is another high-power photomicrograph showing cystic spaces (1) within the acinar pancreas and a normal islet of Langerhans (2).

-

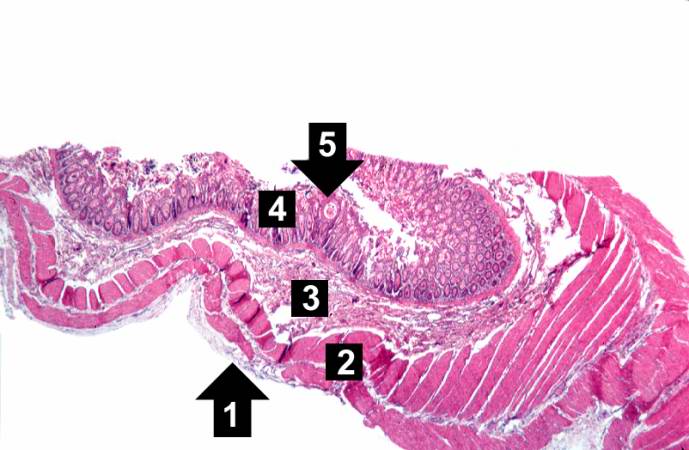

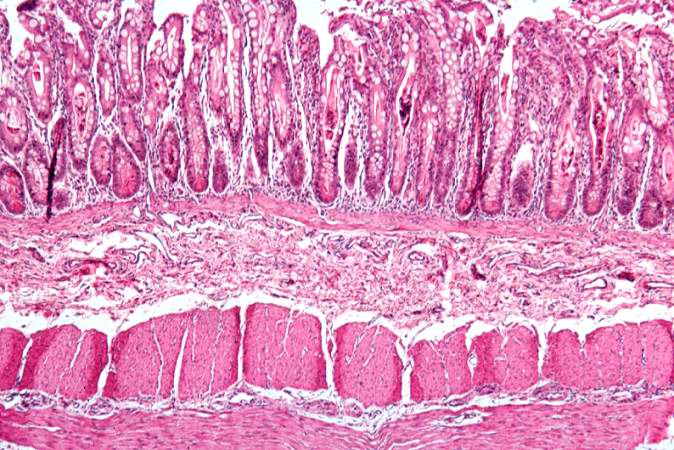

This low-power photomicrograph of intestine shows the normal layers of the intestine, including the serosa (1), the muscularis (2), the submucosa (3), and the mucosal layer (4) with its deep mucosal crypts. There is yet another cystic space within the mucosa (5).

-

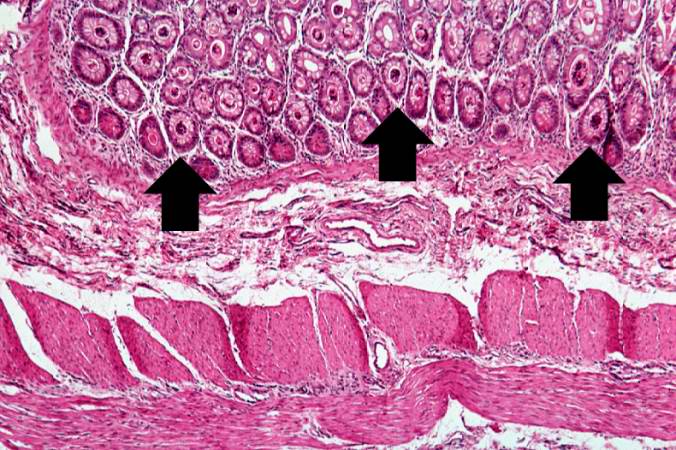

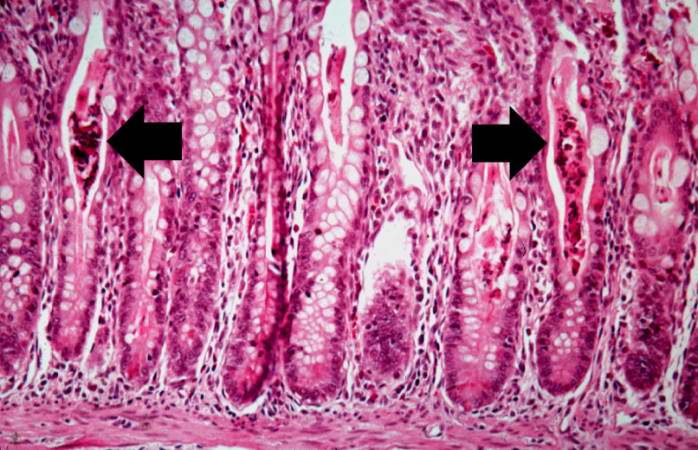

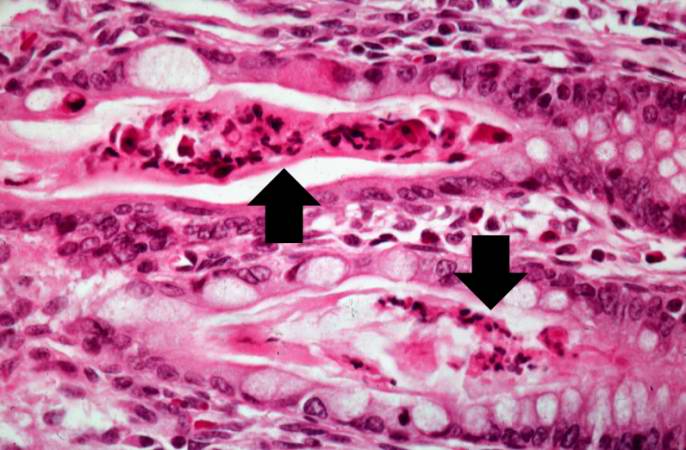

A higher-power photomicrograph shows the bottom of the intestinal crypts and the other normal layers of the intestine. Even at this magnification, accumulations of eosinophilic debris can be seen in many of the intestinal crypts (arrows).

-

This is a higher-power photomicrograph showing the eosinophilic debris in many of the intestinal crypts (arrows).

-

This higher-power photomicrograph shows more clearly the eosinophilic debris (arrows) in the intestinal crypts.

-

This is a low-power photomicrograph from another section of the intestine. Saggital sections of the intestinal crypts show the crypts along their full length, extending to the mucosal surface.

-

A higher-power photomicrograph of intestine shows the vacuolated intestinal epithelial cells lining the crypts and necrotic debris and inspissated secretions within the crypts (arrows).

-

Another high-power photomicrograph of intestine shows the vacuolated intestinal epithelial cells lining the crypts and necrotic debris and inspissated secretions within the crypts (arrows).

Treatment

The cornerstones of management are proactive treatment of airway infection, and encouragement of good nutrition and an active lifestyle. The treatment for cystic fibrosis continues throughout a patient's life, and is aimed at maximizing organ function, and therefore quality of life. At best, current treatments delay the decline in organ function. Treatment typically occurs at specialist multidisciplinary centres, and is tailored to the individual, because of the wide variation in disease symptoms. Targets for therapy are the lungs, gastrointestinal tract (including insulin treatment), the reproductive organs (including Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART)) and psychological support.[17] In addition, therapies such as transplantation and gene therapy aim to cure some of the effects of cystic fibrosis.

The most consistent aspect of therapy in cystic fibrosis is limiting and treating the lung damage caused by thick mucus and infection with the goal of maintaining quality of life. Intravenous, inhaled, and oral antibiotics are used to treat chronic and acute infections. Mechanical devices and inhalation medications are used to alter and clear the thickened mucus.

Antibiotics to treat lung disease

Antibiotics are given whenever pneumonia is suspected or there has been a decline in lung function. Antibiotics are often chosen based on information about prior infections. Many bacteria common in cystic fibrosis are resistant to multiple antibiotics and require weeks of treatment with intravenous antibiotics such as vancomycin, tobramycin, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, and piperacillin. This prolonged therapy often necessitates hospitalization and insertion of a more permanent IV such as a PICC line or Port-a-Cath. Inhaled therapy with antibiotics such as tobramycin and colistin is often given for months at a time in order to improve lung function by impeding the growth of colonized bacteria.[18][19] Oral antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin or azithromycin are sometimes given to help prevent infection or to control ongoing infection.[20] Some individuals spend years between hospitalizations for antibiotics, whereas others require several antibiotic treatments each year.

Several common antibiotics such as tobramycin and vancomycin can cause hearing loss or kidney problems with long-term use. In order to prevent these side-effects, the amount of antibiotics in the blood are routinely measured and adjusted accordingly.

Other methods to treat lung disease

Several mechanical techniques are used to dislodge sputum and encourage its expectoration. In the hospital setting, physical therapy is utilized; a therapist pounds an individual's chest with his or her hands several times a day. Devices that recreate this percussive therapy include the ThAIRapy Vest and the intrapulmonary percussive ventilator (IPV). Newer methods such as Biphasic Cuirass Ventilation, and associated clearance mode available in such devices, now integrate a cough assistance phase, as well as a vibration phase for dislodging secretions. Biphasic Cuirass Ventilation is also shown to provide a bridge to transplantation. These are portable and adapted for home use.[21] Aerobic exercise is of great benefit to people with cystic fibrosis. Not only does exercise increase sputum clearance but it also improves cardiovascular and overall health.

Aerosolized medications that help loosen secretions include dornase alfa and hypertonic saline.[22] Dornase is a recombinant human deoxyribonuclease, which breaks down DNA in the sputum, thus decreasing its viscosity.[23] N-Acetylcysteine may also decrease sputum viscosity, but research and experience have shown its benefits to be minimal. Albuterol and ipratropium bromide are inhaled to increase the size of the small airways by relaxing the surrounding muscles.

As lung disease worsens, breathing support from machines may become necessary. Individuals with CF may need to wear special masks at night that help push air into their lungs. These machines, known as bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) ventilators, help prevent low blood oxygen levels during sleep. BiPAP may also be used during physical therapy to improve sputum clearance.[24] During severe illness, people with CF may need to have a tube placed in their throats and their breathing supported by a ventilator.

Treatment of other aspects of CF

Newborns with meconium ileus typically require surgery, whereas adults with distal intestinal obstruction syndrome typically do not. Treatment of pancreatic insufficiency by replacement of missing digestive enzymes allows the duodenum to properly absorb nutrients and vitamins that would otherwise be lost in the faeces. Even so, most individuals with CF take additional amounts of vitamins A, D, E, and K and eat high-calorie meals. It should be noted, however, that nutritional advice given to patients is, at best, mixed: Often, literature encourages the eating of high-fat foods without differentiating between saturated and unsaturated fats/trans-fats; this lack of clear information runs counter to health advice given to the general population, and creates the risk of further serious health problems for people with cystic fibrosis as they grow older. So far, no large-scale research involving the incidence of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease in adults with cystic fibrosis has been conducted. This is likely due to the fact that the vast majority of people with cystic fibrosis do not live long enough to develop clinically significant atherosclerosis or coronary heart disease.

The diabetes common to many CF patients is typically treated with insulin injections or an insulin pump.[25] Development of osteoporosis can be prevented by increased intake of vitamin D and calcium, and can be treated by bisphosphonates.[26] Poor growth may be avoided by insertion of a feeding tube for increasing calories through supplemental feeds or by administration of injected growth hormone.[27]

Sinus infections are treated by prolonged courses of antibiotics. The development of nasal polyps or other chronic changes within the nasal passages may severely limit airflow through the nose. Sinus surgery is often used to alleviate nasal obstruction and to limit further infections. Nasal steroids such as fluticasone are used to decrease nasal inflammation.[28] Female infertility may be overcome by assisted reproduction technology, particularly embryo transfer techniques. Male infertility may be overcome with intracytoplasmic sperm injection.[29] Third party reproduction is also a possibility for women with CF.

Transplantation and gene therapy

Lung transplantation often becomes necessary for individuals with cystic fibrosis as lung function and exercise tolerance declines. Although single lung transplantation is possible in other diseases, individuals with CF must have both lungs replaced because the remaining lung would contain bacteria that could infect the transplanted lung. A pancreatic or liver transplant may be performed at the same time in order to alleviate liver disease and/or diabetes.[30] Lung transplantation is considered when lung function approaches a point where it threatens survival or requires assistance from mechanical devices.[31]

Gene therapy holds promise as a potential avenue to cure cystic fibrosis. Gene therapy attempts to place a normal copy of the CFTR gene into affected cells. Studies have shown that to prevent the lung manifestations of cystic fibrosis, only 5–10% the normal amount of CFTR gene expression is needed.[32] Many approaches have been theorized and several clinical trials have been initiated but, as of 2006, many hurdles still exist before gene therapy can be successful.[33]

Prognosis

In most cases, CF causes an early death. Average life expectancy is around 36.8 years, although improvements in treatments mean a baby born today could expect to live longer.[34]

Epidemiology

Cystic fibrosis is the most common life-limiting autosomal recessive disease among people of European heritage. In the United States, approximately 30,000 individuals have CF; most are diagnosed by six months of age. Canada has approximately 3,000 citizens with CF. Approximately 1 in 25 people of European descent and 1 in 22 people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent is a carrier of a cystic fibrosis mutation. Although CF is less common in these groups, approximately 1 in 46 Hispanics, 1 in 65 Africans and 1 in 90 Asians carry at least one abnormal CFTR gene.[35][36][37]

Cystic fibrosis is diagnosed in males and females equally. For unclear reasons, males tend to have a longer life expectancy than females.[38] Life expectancy for people with CF depends largely upon access to health care. In 1959, the median age of survival of children with cystic fibrosis was six months. In the United States, the life expectancy for infants born in 2006 with CF is 36.8 years, based upon data compiled by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.[34]

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation also compiles lifestyle information about American adults with CF. In 2004, the foundation reported that 91% had graduated high school and 54% had at least some college education. Employment data revealed 12.6% of adults were disabled and 9.9% were unemployed. Marital information showed that 59% of adults were single and 36% were married or living with a partner. In 2004, 191 American women with CF were pregnant.

Theories about the prevalence of CF

The ΔF508 mutation is estimated to be up to 52,000 years old.[39] Numerous hypotheses have been advanced as to why such a lethal mutation has persisted and spread in the human population. Other common autosomal recessive diseases such as sickle-cell anemia have been found to protect carriers from other diseases, a concept known as heterozygote advantage. Resistance to the following have all been proposed as possible sources of heterozygote advantage:

- Cholera: With the discovery that cholera toxin requires normal host CFTR proteins to function properly, it was hypothesized that carriers of mutant CFTR genes benefited from resistance to cholera and other causes of diarrhea.[40] Further studies have not confirmed this hypothesis.[41][42]

- Typhoid: Normal CFTR proteins are also essential for the entry of Salmonella typhi into cells,[43] suggesting that carriers of mutant CFTR genes might be resistant to typhoid fever. No in vivo study has yet confirmed this. In both cases, the low level of cystic fibrosis outside of Europe, in places where both cholera and typhoid fever are endemic, is not immediately explicable.

- Diarrhoea: It has also been hypothesized that the prevalence of CF in Europe might be connected with the development of cattle domestication. In this hypothesis, carriers of a single mutant CFTR chromosome had some protection from diarrhoea caused by lactose intolerance, prior to the appearance of the mutations that created lactose tolerance.[44]

- Tuberculosis: Poolman and Galvani from Yale University have added another possible explanation - that carriers of the gene have some resistance to TB.[45][46]

History

The name cystic fibrosis refers to the characteristic 'fibrosis' (tissue scarring) of the biliary tract ("cystic" being a generic term for all that is related to the biliary vesicle and/or the bladder), first recognized in the 1930s.[47] Formerly known as cystic fibrosis of the pancreas, this entity has increasingly been labeled simply cystic fibrosis.[48] Although the entire clinical spectrum of CF was not recognized until the 1930s, certain aspects of CF were identified much earlier. Indeed, literature from Germany and Switzerland in the 1700s warned "Wehe dem Kind, das beim Kuß auf die Stirn salzig schmekt, es ist verhext und muss bald sterben," which translates to "Woe is the child kissed on the brow who tastes salty, for he is cursed and soon must die," recognizing the association between the salt loss in CF and illness. Carl von Rokitansky described a case of fetal death with meconium peritonitis, complication of meconium ileus associated with cystic fibrosis. Meconium ileus was first described in 1905 by Karl Landsteiner.[49] In 1936, Guido Fanconi published a paper describing a connection between celiac disease, cystic fibrosis of the pancreas, and bronchiectasis.[50]

In 1938, Dorothy Hansine Andersen published an article titled "Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathological study" in the American Journal of Diseases of Children. In her paper, she described the characteristic cystic fibrosis of the pancreas correlated it with the lung and intestinal disease prominent in CF.[47] She also first hypothesized that CF is a recessive disease and first used pancreatic enzyme replacement to treat affected children. In 1952, Paul di Sant' Agnese discovered abnormalities in sweat electrolytes; the sweat test was developed and improved over the next decade.[51]

In 1988, the first mutation for CF, ΔF508, was discovered by Francis Collins, Lap-Chee Tsui and John R. Riordan on the seventh chromosome. Research has subsequently found over 1000 different mutations that cause CF. Lap-Chee Tsui led a team of researchers at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto that discovered the gene responsible for CF in 1989. Cystic fibrosis represents the first genetic disorder elucidated strictly by the process of reverse genetics. Because mutations in the CFTR gene are typically small, classical genetics techniques were not able to accurately pinpoint the mutated gene.[52] Using protein markers, gene linkage studies were able to map the mutation to chromosome 7. Chromosome walking and jumping techniques were then used to identify and sequence the gene.[53]

Public Awareness

Some children with cystic fibrosis in the United States call their disease 65 Roses because the words are easier to pronounce. This trademarked phrase has been popularized by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. The phrase came into being when it was used by a young boy who had overheard his mother, a volunteer for the Foundation, speaking of his illness. He later informed her that he knew she was working to help with "sixty-five roses"[54] The term has since been used as a symbol by organizations and families of cystic fibrosis victims.

See also

References

- ↑ Davies J et al. Cystic Fibrosis. BMJ. 2007 Dec 15;335(7632):1255–59.

- ↑ Stern, RC. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:487. PMID 9017943

- ↑ ACOG Committee Opinion #325: Update on Carrier Screening for Cystic Fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106:1465.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American College of Medical Genetics. Preconception and prenatal carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Clinical and laboratory guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Washington, DC, October 2001.

- ↑ Elias, S, Annas, GJ, Simpson, JL. Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: Implications for obstetric and gynecologic practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 164:1077. PMID 2014829

- ↑ Tabor A, Philip J, Madsen M, Bang J, Obel EB, Norgaard-Pedersen B. Randomised controlled trial of genetic amniocentesis in 4606 low-risk women. Lancet. 1986 Jun 7;1(8493):1287–93. PMID 2423826

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Saiman L. Microbiology of early CF lung disease. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5 Suppl A:S367-9. PMID 14980298

- ↑ Tummler B, Koopmann U, Grothues D, Weissbrodt H, Steinkamp G, von der Hardt H. Nosocomial acquisition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1991 Jun;29(6):1265–7. PMID 1907611

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pseudomonas cepacia at summer camps for persons with cystic fibrosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993 Jun 18;42(23):456-9. PMID 7684813

- ↑ Pegues DA, Carson LA, Tablan OC, FitzSimmons SC, Roman SB, Miller JM, Jarvis WR.Acquisition of Pseudomonas cepacia at summer camps for patients with cystic fibrosis. Summer Camp Study Group. J Pediatr. 1994 May;124(5 Pt 1):694–702. PMID 7513755

- ↑ Pankhurst CL, Philpott-Howard J. The environmental risk factors associated with medical and dental equipment in the transmission of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia in cystic fibrosis patients. J Hosp Infect. 1996 Apr;32(4):249-55. PMID 8744509

- ↑ Jones AM, Govan JR, Doherty CJ, Dodd ME, Isalska BJ, Stanbridge TN, Webb AK. Identification of airborne dissemination of epidemic multiresistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa at a CF centre during a cross infection outbreak. Thorax. 2003 Jun;58(6):525-7. PMID 12775867

- ↑ Hoiby N. Isolation and treatment of cystic fibrosis patients with lung infections caused by Pseudomonas (Burkholderia) cepacia and multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Neth J Med. 1995 Jun;46(6):280-7. PMID 7643943

- ↑ Prevalence of ΔF508, G551D, G542X, R553X mutations among cystic fibrosis patients in the North of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2005; 38:11–15. PMID 15665983

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2

- ↑ Short DB, Trotter KW, Reczek D, Kreda SM, Bretscher A, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ, Milgram SL. An apical PDZ protein anchors the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1998 Jul 31;273(31):19797-801. PMID 9677412

- ↑ Davies J et al. Cystic Fibrosis. BMJ. 2007 Dec 15;335(7632):1255–59.

- ↑ Pai VB, Nahata MC. Efficacy and safety of aerosolized tobramycin in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001 Oct;32(4):314-27. Review. PMID 11568993

- ↑ Westerman EM, Le Brun PP, Touw DJ, Frijlink HW, Heijerman HG. Effect of nebulized colistin sulphate and colistin sulphomethate on lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. J Cyst Fibros. 2004 Mar;3(1):23-8. PMID 15463883

- ↑ Hansen CR, Pressler T, Koch C, Hoiby N.Long-term azithromycin treatment of cystic fibrosis patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection; an observational cohort study. J Cyst Fibros. 2005 Mar;4(1):35–40. PMID 15752679

- ↑ van der Schans C, Prasad A, Main E. Chest physiotherapy compared to no chest physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001401. Review. PMID 10796781

- ↑ Kuver R, Lee SP. Hypertonic saline for cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 27;354(17):1848–51; author reply 1848–51. PMID 16642591

- ↑ Lieberman J. Dornase aerosol effect on sputum viscosity in cases of cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 1968 Jul 29;205(5):312-3. PMID 5694947

- ↑ Moran F, Bradley J. Non-invasive ventilation for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD002769. Review. PMID 12804435

- ↑ Onady GM, Stolfi A. Insulin and oral agents for managing cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jul 20;(3):CD004730. Review. PMID 16034943

- ↑ Conway SP, Oldroyd B, Morton A, Truscott JG, Peckham DG. Effect of oral bisphosphonates on bone mineral density and body composition in adult patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. Thorax. 2004 Aug;59(8):699–703. PMID 15282392

- ↑ Hardin DS, Rice J, Ahn C, Ferkol T, Howenstine M, Spears S, Prestidge C, Seilheimer DK, Shepherd R. Growth hormone treatment enhances nutrition and growth in children with cystic fibrosis receiving enteral nutrition.J Pediatr. 2005 Mar;146(3):324-8. PMID 15756212

- ↑ Marks SC, Kissner DG. Management of sinusitis in adult cystic fibrosis. Am J Rhinol. 1997 Jan-Feb;11(1):11-4. PMID 9065342

- ↑ Phillipson GT, Petrucco OM, Matthews CD. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens, cystic fibrosis mutation analysis and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 2000 Feb;15(2):431-5. PMID 10655317

- ↑ Simultaneous liver and pancreas transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Transplant Proc. 2005 Oct;37(8):3567–9. PMID 16298663

- ↑ Belkin RA, Henig NR, Singer LG, Chaparro C, Rubenstein RC, Xie SX, Yee JY, Kotloff RM, Lipson DA, Bunin GR. Risk factors for death of patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Mar 15;173(6):659-66. Epub 2005 Dec 30. PMID 16387803

- ↑ Ramalho AS, Beck S, Meyer M, Penque D, Cutting GR, Amaral MD. Five percent of normal cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mRNA ameliorates the severity of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002 27(5):619-27. PMID 12397022

- ↑ Tate S, Elborn S. Progress towards gene therapy for cystic fibrosis.Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2005 Mar;2(2):269-80. Review. PMID 16296753

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "New Statistics Show CF Patients Living Longer". Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. April 26, 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-09. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Rosenstein BJ and Cutting GR. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: a consensus statement. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Panel. J Pediatr. 1998 Apr;132(4):589-95. Review. PMID 9580754

- ↑ Hamosh A, Fitz-Simmons SC, Macek M Jr, Knowles MR, Rosenstein BJ, Cutting GR. Comparison of the clinical manifestations of cystic fibrosis in black and white patients. J Pediatr. 1998 Feb;132(2):255-9. PMID 9506637

- ↑ Kerem B, Chiba-Falek O, Kerem E. Cystic fibrosis in Jews: frequency and mutation distribution. Genet Test. 1997;1(1):35-9. Review. PMID 10464623

- ↑ Rosenfeld, M, Davis, R, FitzSimmons, S, et al Gender gap in cystic fibrosis mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1997 145,794–803

- ↑ Wiuf C. Do delta F508 heterozygotes have a selective advantage? Genet Res. 2001 Aug;78(1):41-7. PMID 11556136

- ↑ Gabriel SE, Brigman KN, Koller BH, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote resistance to cholera toxin in the cystic fibrosis mouse model. Science. 1994 Oct 7;266(5182):107-9. PMID 7524148

- ↑ Cuthbert AW, Halstead J, Ratcliff R, Colledge WH, Evans MJ. The genetic advantage hypothesis in cystic fibrosis heterozygotes: a murine study. J Physiol. 1995 Jan 15;482 (Pt 2):449-54. PMID 7714835

- ↑ Hogenauer C, Santa Ana CA, Porter JL, Millard M, Gelfand A, Rosenblatt RL, Prestidge CB, Fordtran JS. Active intestinal chloride secretion in human carriers of cystic fibrosis mutations: an evaluation of the hypothesis that heterozygotes have subnormal active intestinal chloride secretion. Am J Hum Genet. 2000 Dec;67(6):1422–7. Epub 2000 Oct 30. PMID 11055897.

- ↑ Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi T, Meluleni G, Mueschenborn SS, Banting G, Ratcliff R, Evans MJ, Colledge WH. Salmonella typhi uses CFTR to enter intestinal epithelial cells. Nature. 1998 May 7;393(6680):79–82. PMID 9590693

- ↑ Modiano G, Ciminelli BM, Pignatti PF. Cystic Fibrosis: Cystic fibrosis and lactase persistence: a possible correlation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007 Mar;15(3):255-9. PMID: 17180122.

- ↑ Cystic fibrosis gene protects against tuberculosis

- ↑ Footprint fears for new TB threat

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Andersen DH. Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathological study. Am J Dis Child 1938; 56:344–399

- ↑ "Cystic Fibrosis; CF - Mucoviscidosis". Entrez. April 26, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-28. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Busch R. On the history of cystic fibrosis. Acta Univ Carol [Med] (Praha). 1990;36(1-4):13-5. PMID 2130674

- ↑ Fanconi G, Uehlinger E, Knauer.C. Das coeliakiesyndrom bei angeborener zysticher pankreasfibromatose und bronchiektasien. Wien Med Wschr 1936; 86:753–756.

- ↑ Di Sant' Agnese PA, Darling RC, Perera GA, et al. Abnormal electrolyte composition of sweat in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas: clinical implications and relationship to the disease. Pediatrics 1953; 12:549–563.

- ↑ Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989 Sep 8;245(4922):1066–73. Erratum in: Science 1989 Sep 29;245(4925):1437. PMID 2475911

- ↑ Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping.Science. 1989 Sep 8;245(4922):1059–65. PMID 2772657

- ↑ "The Story of 65 Roses". Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Cystic Fibrosis Worldwide

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

- Cystic fibrosis pictures (Univ Geneva, Switzerland)

- cf at NIH/UW GeneTests

- Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network

- Search GeneCards for genes envolved in Cystic Fibrosis

Template:SIB

Template:Other metabolic pathology

Template:Link FA

ar:تليف كيسي ca:Fibrosi quística cs:Cystická fibróza cy:Ffibrosis systig da:Cystisk fibrose de:Mukoviszidose et:Tsüstiline fibroos eu:Fibrosi kistiko fa:فیبروز کیستیک it:Fibrosi cistica he:סיסטיק פיברוזיס hu:Cisztás fibrózis nl:Taaislijmziekte no:Cystisk fibrose nn:Cystisk fibrose sq:Fibroza kistike simple:Cystic fibrosis sk:Cystická fibróza sr:Цистична фиброза fi:Kystinen fibroosi sv:Cystisk fibros uk:Кістозний фіброз