Autism

For patient information click here

| Autism | |

| |

|---|---|

| Repetitively stacking or lining up objects may indicate autism.[1] | |

| ICD-10 | F84.0 |

| ICD-9 | 299.0 |

| OMIM | 209850 |

| DiseasesDB | 1142 |

| MedlinePlus | 001526 |

| MeSH | D001321 |

|

Autism Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Autism On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Autism |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Mechanism

Despite extensive investigation, how autism occurs is not well understood. Its mechanism can be divided into two areas: the pathophysiology of brain structures and processes associated with autism, and the neuropsychological linkages between brain structures and behaviors.[2] The behaviors appear to have multiple pathophysiologies.[3]

Pathophysiology

Autism appears to result from developmental factors that affect many or all functional brain systems,[4] and to disturb the course of brain development more than the final product.[5] Neuroanatomical studies and the associations with teratogens strongly suggest that autism's mechanism includes alteration of brain development soon after conception.[6] This localized anomaly appears to start a cascade of pathological events in the brain that are significantly influenced by environmental factors.[7] Although many major structures of the human brain have been implicated, almost all postmortem studies have been of individuals who also had mental retardation, making it difficult to draw conclusions.[5] Brain weight and volume and head circumference tend to be greater in autistic children.[8] The cellular and molecular bases of pathological early overgrowth are not known, nor is it known whether the overgrown neural systems cause autism's characteristic signs. Current hypotheses include:

- An excess of neurons that causes local overconnectivity in key brain regions.[9]

- Disturbed neuronal migration during early gestation.[10][11]

- Unbalanced excitatory-inhibitory networks.[11]

- Abnormal formation of synapses and dendritic spines.[11]

Interactions between the immune system and the nervous system begin early during embryogenesis, and successful neurodevelopment depends on a balanced immune response. Several symptoms consistent with a poorly regulated immune response have been reported in autistic children. It is possible that aberrant immune activity during critical periods of neurodevelopment is part of the mechanism of some forms of ASD.[12] As autoantibodies have not been associated with pathology, are found in diseases other than ASD, and are not always present in ASD,[13] the relationship between immune disturbances and autism remains unclear and controversial.[10]

Several neurotransmitter abnormalities have been detected in autism, notably increased blood levels of serotonin. Whether these lead to structural or behavioral abnormalities is unclear.[2] Also, some inborn errors of metabolism are associated with autism but probably account for less than 5% of cases.[14]

The mirror neuron system (MNS) theory of autism hypothesizes that distortion in the development of the MNS interferes with imitation and leads to autism's core features of social impairment and communication difficulties. The MNS operates when an animal performs an action or observes another animal of the same species perform the same action. The MNS may contribute to an individual's understanding of other people by enabling the modeling of their behavior via embodied simulation of their actions, intentions, and emotions.[15] Several studies have tested this hypothesis by demonstrating structural abnormalities in MNS regions of individuals with ASD, delay in the activation in the core circuit for imitation in individuals with Asperger's, and a correlation between reduced MNS activity and severity of the syndrome in children with ASD.[16] However, individuals with autism also have abnormal brain activation in many circuits outside the MNS[17] and the MNS theory does not explain the normal performance of autistic children on imitation tasks that involve a goal or object.[18]

A 2008 study of autistic adults found evidence for altered functional organization of the task-negative network, a large-scale brain network involved in social and emotional processing, with intact organization of the task-positive network, used in sustained attention and goal-directed thinking.[19] A 2008 brain-imaging study found a specific pattern of signals in the cingulate cortex which differs in individuals with ASD.[20]

The underconnectivity theory of autism hypothesizes that autism is marked by underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.[21] Evidence for this theory has been found in functional neuroimaging studies on autistic individuals[22] and by a brain wave study that suggested that adults with ASD have local overconnectivity in the cortex and weak functional connections between the frontal lobe and the rest of the cortex.[23] Other evidence suggests the underconnectivity is mainly within each hemisphere of the cortex and that autism is a disorder of the association cortex.[24]

Neuropsychology

Two major categories of cognitive theories have been proposed about the links between autistic brains and behavior.

The first category focuses on deficits in social cognition. Hyper-systemizing hypothesizes that autistic individuals can systematize—that is, they can develop internal rules of operation to handle internal events—but are less effective at empathizing by handling events generated by other agents.[25] It extends the extreme male brain theory, which hypothesizes that autism is an extreme case of the male brain, defined psychometrically as individuals in whom systemizing is better than empathizing.[26] This in turn is related to the earlier theory of mind, which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from an inability to ascribe mental states to oneself and others. The theory of mind is supported by autistic children's atypical responses to the Sally-Anne test for reasoning about others' motivations,[27] and is mapped well from the mirror neuron system theory of autism.[16]

The second category focuses on nonsocial or general processing. Executive dysfunction hypothesizes that autistic behavior results in part from deficits in flexibility, planning, and other forms of executive function. A strength of the theory is predicting stereotyped behavior and narrow interests;[28] a weakness is that executive function deficits are not found in young autistic children.[29] Weak central coherence theory hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in autism. One strength of this theory is predicting special talents and peaks in performance in autistic people.[30] A related theory—enhanced perceptual functioning—focuses more on the superiority of locally oriented and perceptual operations in autistic individuals.[31] These theories map well from the underconnectivity theory of autism.

Neither category is satisfactory on its own; social cognition theories poorly address autism's rigid and repetitive behaviors, while the nonsocial theories have difficulty explaining social impairment and communication difficulties.[32] A combined theory based on multiple deficits may prove to be more useful.[33]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on behavior, not cause or mechanism.[3][34] Autism is defined in the DSM-IV-TR as exhibiting at least six symptoms total, including at least two symptoms of qualitative impairment in social interaction, at least one symptom of qualitative impairment in communication, and at least one symptom of restricted and repetitive behavior. Sample symptoms include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with parts of objects. Onset must be prior to age three years, with delays or abnormal functioning in either social interaction, language as used in social communication, or symbolic or imaginative play. The disturbance must not be better accounted for by Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder.[35] ICD-10 uses essentially the same definition.[36]

Several diagnostic instruments are available. Two are commonly used in autism research: the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) is a semistructured parent interview, and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) uses observation and interaction with the child. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) is used widely in clinical environments to assess severity of autism based on observation of children.[37]

A pediatrician commonly performs a preliminary investigation by taking developmental history and physically examining the child. If warranted, diagnosis and evaluations are conducted with help from ASD specialists, observing and assessing cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions. A differential diagnosis for ASD at this stage might also consider mental retardation, hearing impairment, and a specific language impairment[38] such as Landau-Kleffner syndrome.[39] ASD can sometimes be diagnosed by age 14 months, although diagnosis becomes increasingly stable over the first three years of life: for example, a one-year-old who meets diagnostic criteria for ASD is less likely than a three-year-old to continue to do so a few years later.[40] In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice.[38] A 2006 U.S. study found the average age of first evaluation by a qualified professional was 48 months and of formal ASD diagnosis was 61 months, reflecting an average 13-month delay, all far above recommendations.[41]

Clinical genetics evaluations are often done once ASD is diagnosed, particularly when other symptoms already suggest a genetic cause.[42] Although genetic technology allows clinical geneticists to link an estimated 40% of cases to genetic causes,[43] consensus guidelines in the U.S. and UK are limited to high-resolution chromosome and fragile X testing.[42] As new genetic tests are developed several ethical, legal, and social issues will emerge. Commercial availability of tests may precede adequate understanding of how to use test results, given the complexity of autism's genetics.[44] Metabolic and neuroimaging tests are sometimes helpful, but are not routine.[42]

Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases, and much of the recent increase in the number of reported ASD cases is likely due to changes in diagnostic practices. The increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has given providers incentives to diagnose ASD, resulting in some overdiagnosis of children with uncertain symptoms. Conversely, the cost of screening and diagnosis and the challenge of obtaining payment can inhibit or delay diagnosis.[45] It is particularly hard to diagnose autism among the visually impaired, partly because some of its diagnostic criteria depend on vision, and partly because autistic symptoms overlap with those of common blindness syndromes.[46]

The symptoms of autism and ASD begin early in childhood but are occasionally missed. Adults may seek retrospective diagnoses to help them or their friends and family understand themselves, to help their employers make adjustments, or in some locations to claim disability living allowances or other benefits.[47]

Management

The main goals of treatment are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. No single treatment is best and treatment is typically tailored to the child's needs. Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills,[48] and often improve functioning and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors;[49] claims that intervention by age two to three years is crucial[50] are not substantiated.[51] Available approaches include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy.[48] Educational interventions have some effectiveness in children: intensive ABA treatment has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing global functioning in preschool children[52] and is well-established for improving intellectual performance of young children.[49] The limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.[53]

Many medications are used to treat problems associated with ASD.[54] More than half of U.S. children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics.[55] Aside from antipsychotics,[56] there is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD.[57] A person with ASD may respond atypically to medications, the medications can have adverse effects, and no known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.[58][59]

Although many alternative therapies and interventions are available, few are supported by scientific studies.[29][60][61] Treatment approaches have little empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance.[62] Scientific evidence appears to matter less to service providers than program marketing, training availability, and parent requests.[63] Although most alternative treatments, such as melatonin, have only mild adverse effects,[64] a 2008 study found that autistic boys on casein-free diets have significantly thinner bones,[65] and botched chelation therapy killed a five-year-old autistic boy in 2005.[66]

Treatment is expensive; indirect costs are more so. A U.S. study estimated an average cost of $3.2 million in 2003 U.S. dollars for someone born in 2000, with about 10% medical care, 30% extra education and other care, and 60% lost economic productivity.[67] Publicly supported programs are often inadequate or inappropriate for a given child, and unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical or therapy expenses are associated with likelihood of family financial problems;[68] a 2008 U.S. study found a 14% average loss of annual income in families of children with ASD.[69] After childhood, key treatment issues include residential care, job training and placement, sexuality, social skills, and estate planning.[61]

Prognosis

There is no cure.[48] Children recover occasionally, sometimes after intensive treatment and sometimes not; it is not known how often this happens.[49] Most children with autism lack social support, meaningful relationships, future employment opportunities or self-determination.[62] Although core difficulties remain, symptoms often become less severe in later childhood.[51] Few high-quality studies address long-term prognosis. Some adults show modest improvement in communication skills, but a few decline; no study has focused on autism after midlife.[70] Acquiring language before age six, having IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely with severe autism.[71] A 2004 British study of 68 adults who were diagnosed before 1980 as autistic children with IQ above 50 found that 12% achieved a high level of independence as adults, 10% had some friends and were generally in work but required some support, 19% had some independence but were generally living at home and needed considerable support and supervision in daily living, 46% needed specialist residential provision from facilities specializing in ASD with a high level of support and very limited autonomy, and 12% needed high-level hospital care.[72] A 2005 Swedish study of 78 adults that did not exclude low IQ found worse prognosis; for example, only 4% achieved independence.[73] A 2008 Canadian study of 48 young adults diagnosed with ASD as preschoolers found outcomes ranging through poor (46%), fair (32%), good (17%), and very good (4%); only 56% had ever been employed, most in volunteer, sheltered or part time work.[74] Changes in diagnostic practice and increased availability of effective early intervention make it unclear whether these findings can be generalized to recently diagnosed children.[75]

Epidemiology

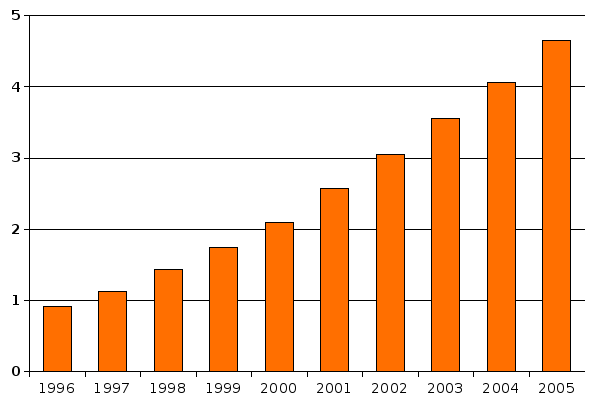

Most recent reviews tend to estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for autism and close to 6 per 1,000 for ASD;[75] because of inadequate data, these numbers may underestimate ASD's true prevalence.[42] PDD-NOS is the vast majority of ASD, Asperger's is about 0.3 per 1,000 and the remaining ASD forms are much rarer.[76] The number of reported cases of autism increased dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s. This increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness,[77] though as-yet-unidentified contributing environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[78] It is unknown whether autism's prevalence increased during the same period. An increase in prevalence would suggest directing more attention and funding toward changing environmental factors instead of continuing to focus on genetics.[79]

The risk of autism is associated with several prenatal and perinatal risk factors. A 2007 review of risk factors found associated parental characteristics that included advanced maternal age, advanced paternal age, and maternal place of birth outside Europe or North America, and also found associated obstetric conditions that included low birth weight and gestation duration, and hypoxia during childbirth.[80]

Autism is associated with several other conditions:

- Genetic disorders. About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[81] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[82]

- Mental retardation. A 2001 British study of 26 autistic children found about 30% with intelligence in the normal range (IQ above 70), 50% with mild to moderate retardation, and about 20% with severe to profound retardation (IQ below 35). For ASD other than autism the association is much weaker: the same study reported about 94% of 65 children with PDD-NOS or Asperger's had normal intelligence.[83]

- Maleness. Boys are at higher risk for autism than girls. The ASD sex ratio averages 4.3:1 and is greatly modified by cognitive impairment: it may be close to 2:1 with mental retardation and more than 5.5:1 without.[75]

- Epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[84]

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.[14]

History

A few examples of autistic symptoms and treatments were described long before autism was named. The Table Talk of Martin Luther contains a story of a 12-year-old boy who may have been severely autistic.[85] According to Luther's notetaker Mathesius, Luther thought the boy was a soulless mass of flesh possessed by the devil, and suggested that he be suffocated.[86] Victor of Aveyron, a feral child caught in 1798, showed several signs of autism; the medical student Jean Itard treated him with a behavioral program designed to help him form social attachments and to induce speech via imitation.[87]

The New Latin word autismus (English translation autism) was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1910 as he was defining symptoms of schizophrenia. He derived it from the Greek word autos (αὐτός, meaning self), and used it to mean morbid self-admiration, referring to "autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance."[88]

The word autism first took its modern sense in 1938 when Hans Asperger of the Vienna University Hospital adopted Bleuler's terminology "autistic psychopaths" in a lecture in German about child psychology.[89] Asperger was investigating a form of ASD now known as Asperger syndrome, though for various reasons it was not widely recognized as a separate diagnosis until 1981.[87] Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital first used autism in its modern sense in English when he introduced the label early infantile autism in a 1943 report of 11 children with striking behavioral similarities.[90] Almost all the characteristics described in Kanner's first paper on the subject, notably "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness", are still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders.[32] It is not known whether Kanner derived the term independently of Asperger.[91]

Kanner's reuse of autism led to decades of confused terminology like "infantile schizophrenia", and child psychiatry's focus on maternal deprivation during the mid-1900s led to misconceptions of autism as an infant's response to "refrigerator mothers". Starting in the late 1960s autism was established as a separate syndrome by demonstrating that it is lifelong, distinguishing it from mental retardation and schizophrenia and from other developmental disorders, and demonstrating the benefits of involving parents in active programs of therapy.[92] As late as the mid-1970s there was little evidence of a genetic role in autism; now it is thought to be one of the most heritable of all psychiatric conditions.[93] The rise of parent organizations and the destigmatization of childhood ASD have deeply affected how we view ASD, its boundaries, and its treatments.[87] The Internet has helped autistic individuals bypass nonverbal cues and emotional sharing that they find so hard to deal with, and has given them a way to form online communities and work remotely.[94] Sociological and cultural aspects of autism have developed: some in the community seek a cure, while others believe that autism is simply another way of being.[33][95]

References

- ↑

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Penn HE (2006). "Neurobiological correlates of autism: a review of recent research". Child Neuropsychol. 12 (1): 57–79. doi:10.1080/09297040500253546. PMID 16484102.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 London E (2007). "The role of the neurobiologist in redefining the diagnosis of autism". Brain Pathol. 17 (4): 408–11. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00103.x. PMID 17919126.

- ↑ Müller RA (2007). "The study of autism as a distributed disorder". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 13 (1): 85–95. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20141. PMID 17326118.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW (2008). "Neuroanatomy of autism". Trends Neurosci. 31 (3): 137–45. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. PMID 18258309.

- ↑

- ↑ Casanova MF (2007). "The neuropathology of autism". Brain Pathol. 17 (4): 422–33. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00100.x. PMID 17919128.

- ↑ DiCicco-Bloom E, Lord C, Zwaigenbaum L; et al. (2006). "The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder". J Neurosci. 26 (26): 6897–906. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-06.2006. PMID 16807320.

- ↑ Courchesne E, Pierce K, Schumann CM; et al. (2007). "Mapping early brain development in autism". Neuron. 56 (2): 399–413. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016. PMID 17964254.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Schmitz C, Rezaie P (2008). "The neuropathology of autism: where do we stand?". Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 34 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00872.x. PMID 17971078.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Persico AM, Bourgeron T (2006). "Searching for ways out of the autism maze: genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues". Trends Neurosci. 29 (7): 349–58. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.010. PMID 16808981.

- ↑ Ashwood P, Wills S, Van de Water J (2006). "The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research". J Leukoc Biol. 80 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1189/jlb.1205707. PMID 16698940.

- ↑ Wills S, Cabanlit M, Bennett J, Ashwood P, Amaral D, Van de Water J (2007). "Autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1107: 79–91. doi:10.1196/annals.1381.009. PMID 17804535.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P (2008). "Autism and metabolic diseases". J Child Neurol. 23 (3): 307–14. doi:10.1177/0883073807308698. PMID 18079313.

- ↑ MNS and autism:

- Ramachandran VS, Oberman LM (2006). "Broken mirrors: a theory of autism" (PDF). Sci Am. 295 (5): 62–9. PMID 17076085. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- Dinstein I, Thomas C, Behrmann M, Heeger DJ (2008). "A mirror up to nature". Curr Biol. 18 (1): R13–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.004. PMID 18177704.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Iacoboni M, Dapretto M (2006). "The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction". Nat Rev Neurosci. 7 (12): 942–51. doi:10.1038/nrn2024. PMID 17115076.

- ↑ Frith U, Frith CD (2003). "Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing" (PDF). Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 358 (1431): 459–73. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1218. PMID 12689373.

- ↑ Hamilton AFdC (2008). "Emulation and mimicry for social interaction: a theoretical approach to imitation in autism". Q J Exp Psychol. 61 (1): 101–15. doi:10.1080/17470210701508798. PMID 18038342.

- ↑ Kennedy DP, Courchesne E (2008). "The intrinsic functional organization of the brain is altered in autism". Neuroimage. 38 (4): 1877–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.052. PMID 18083565.

- ↑ Chiu PH, Kayali MA, Kishida KT; et al. (2008). "Self responses along cingulate cortex reveal quantitative neural phenotype for high-functioning autism". Neuron. 57 (3): 463–73. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.020. PMID 18255038. Lay summary – Technol Rev (2007-02-07).

- ↑ Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ (2007). "Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry". Cereb Cortex. 17 (4): 951–61. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl006. PMID 16772313.

- ↑ Williams DL, Goldstein G, Minshew NJ (2006). "Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing". Child Neuropsychol. 12 (4–5): 279–98. doi:10.1080/09297040600681190. PMC 1803025. PMID 16911973.

- ↑ Murias M, Webb SJ, Greenson J, Dawson G (2007). "Resting state cortical connectivity reflected in EEG coherence in individuals with autism". Biol Psychiatry. 62 (3): 270–3. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.012. PMID 17336944.

- ↑ Minshew NJ, Williams DL (2007). "The new neurobiology of autism: cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization". Arch Neurol. 64 (7): 945–50. PMID 17620483.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S (2006). "The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 30 (5): 865–72. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010. PMID 16519981.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S (2002). "The extreme male brain theory of autism". Trends Cogn Sci. 6 (6): 248–54. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01904-6. PMID 12039606.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U (1985). "Does the autistic child have a 'theory of mind'?" (PDF). Cognition. 21 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8. PMID 2934210. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ↑ Hill EL (2004). "Executive dysfunction in autism". Trends Cogn Sci. 8 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2004.01.001. PMID 14697400.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1

- ↑ Happé F, Frith U (2006). "The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders". J Autism Dev Disord. 36 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0. PMID 16450045.

- ↑ Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J (2006). "Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception". J Autism Dev Disord. 36 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7. PMID 16453071.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R (2006). "Time to give up on a single explanation for autism". Nat Neurosci. 9 (10): 1218–20. doi:10.1038/nn1770. PMID 17001340.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Rajendran G, Mitchell P (2007). "Cognitive theories of autism". Dev Rev. 27 (2): 224–60. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2007.02.001.

- ↑ Baird G, Cass H, Slonims V (2003). "Diagnosis of autism". BMJ. 327 (7413): 488–93. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. PMID 12946972.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Diagnostic criteria for 299.00 Autistic Disorder". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR) ed.). ISBN 0890420254. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2006). "F84. Pervasive developmental disorders". International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th ed. (ICD-10) ed.). Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Dover CJ, Le Couteur A (2007). "How to diagnose autism". Arch Dis Child. 92 (6): 540–5. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.086280. PMID 17515625.

- ↑ Mantovani JF (2000). "Autistic regression and Landau-Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion?". Dev Med Child Neurol. 42 (5): 349–53. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2000.tb00104.x. PMID 10855658.

- ↑ Landa RJ (2008). "Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in the first 3 years of life". Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 4 (3): 138–47. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0731. PMID 18253102.

- ↑ Wiggins LD, Baio J, Rice C (2006). "Examination of the time between first evaluation and first autism spectrum diagnosis in a population-based sample". J Dev Behav Pediatr. 27 (2 Suppl): S79–87. PMID 16685189.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Caronna EB, Milunsky JM, Tager-Flusberg H (2008). "Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers". Arch Dis Child. 93 (6): 518–23. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076.

- ↑ Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ (2008). "Genetics evaluation for the etiologic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders". Genet Med. 10 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815efdd7. PMID 18197051. Lay summary – Medical News Today (2008-02-07).

- ↑ McMahon WM, Baty BJ, Botkin J (2006). "Genetic counseling and ethical issues for autism". Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 142C (1): 52–7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30082. PMID 16419100.

- ↑ Shattuck PT, Grosse SD (2007). "Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 13 (2): 129–35. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20143. PMID 17563895.

- ↑ Cass H (1998). "Visual impairment and autism: current questions and future research". Autism. 2 (2): 117–38. doi:10.1177/1362361398022002.

- ↑ "Diagnosis: how can it benefit me as an adult?". National Autistic Society. 2005. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Myers SM, Johnson CP, Council on Children with Disabilities (2007). "Management of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics. 120 (5): 1162–82. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2362. PMID 17967921. Lay summary – AAP (2007-10-29).

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Rogers SJ, Vismara LA (2008). "Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism". J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 37 (1): 8–38. doi:10.1080/15374410701817808. PMID 18444052.

- ↑ Pettus A (2008). "A spectrum of disorders". Harv Mag. 110 (3): 27–31, 89–91.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Howlin P (2006). "Autism spectrum disorders". Psychiatry. 5 (9): 320–4. doi:10.1053/j.mppsy.2006.06.007.

- ↑ Eikeseth S (2008). "Outcome of comprehensive psycho-educational interventions for young children with autism". Res Dev Disabil. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.003. PMID 18385012.

- ↑ Van Bourgondien ME, Reichle NC, Schopler E (2003). "Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism". J Autism Dev Disord. 33 (2): 131–40. doi:10.1023/A:1022931224934. PMID 12757352.

- ↑ Leskovec TJ, Rowles BM, Findling RL (2008). "Pharmacological treatment options for autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents". Harv Rev Psychiatry. 16 (2): 97–112. doi:10.1080/10673220802075852. PMID 18415882.

- ↑ Oswald DP, Sonenklar NA (2007). "Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 17 (3): 348–55. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.17303. PMID 17630868.

- ↑ Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ (2008). "Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism". J Clin Invest. 118 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1172/JCI32483. PMID 18172517.

- ↑ Lack of research on drug treatments:

- Angley M, Young R, Ellis D, Chan W, McKinnon R (2007). "Children and autism—part 1—recognition and pharmacological management" (PDF). Aust Fam Physician. 36 (9): 741–4. PMID 17915375.

- Broadstock M, Doughty C, Eggleston M (2007). "Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder". Autism. 11 (4): 335–48. doi:10.1177/1362361307078132. PMID 17656398.

- ↑ Template:Cite paper

- ↑ Buitelaar JK (2003). "Why have drug treatments been so disappointing?". Novartis Found Symp. 251: 235–44, discussion 245–9, 281–97. doi:10.1002/0470869380.ch14. PMID 14521196.

- ↑ Lack of support for interventions:

- Francis K (2005). "Autism interventions: a critical update" (PDF). Dev Med Child Neurol. 47 (7): 493–9. doi:10.1017/S0012162205000952. PMID 15991872.

- Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ (2008). "Social skills interventions for children with Asperger's syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations". J Autism Dev Disord. 38 (2): 353–61. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4. PMID 17641962.

- Schechtman MA (2007). "Scientifically unsupported therapies in the treatment of young children with autism spectrum disorders" (PDF). Pediatr Ann. 36 (8): 497–8, 500–2, 504–5. PMID 17849608.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Aman MG (2005). "Treatment planning for patients with autism spectrum disorders". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 10): 38–45. PMID 16401149.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Burgess AF, Gutstein SE (2007). "Quality of life for people with autism: raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes". Child Adolesc Ment Health. 12 (2): 80–6. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00432.x.

- ↑ Stahmer AC, Collings NM, Palinkas LA (2005). "Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers". Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 20 (2): 66–79. PMC 1350798. PMID 16467905.

- ↑ Angley M, Semple S, Hewton C, Paterson F, McKinnon R (2007). "Children and autism—part 2—management with complementary medicines and dietary interventions" (PDF). Aust Fam Physician. 36 (10): 827–30. PMID 17925903.

- ↑ Hediger ML, England LJ, Molloy CA, Yu KF, Manning-Courtney P, Mills JL (2008). "Reduced bone cortical thickness in boys with autism or autism spectrum disorder". J Autism Dev Disord. 38 (5): 848–56. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0453-6. PMID 17879151. Lay summary – NIH News (2008-01-29).

- ↑ Brown MJ, Willis T, Omalu B, Leiker R (2006). "Deaths resulting from hypocalcemia after administration of edetate disodium: 2003–2005". Pediatrics. 118 (2): e534–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0858. PMID 16882789.

- ↑ Ganz ML (2007). "The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (4): 343–9. PMID 17404130. Lay summary – Harvard School of Public Health (2006-04-25).

- ↑ Sharpe DL, Baker DL (2007). "Financial issues associated with having a child with autism". J Fam Econ Iss. 28 (2): 247–64. doi:10.1007/s10834-007-9059-6.

- ↑ Montes G, Halterman JS (2008). "Association of childhood autism spectrum disorders and loss of family income". Pediatrics. 121 (4): e821–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1594. PMID 18381511.

- ↑ Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Abbeduto L, Greenberg JS (2004). "Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism" (PDF). Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 10 (4): 234–47. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20038. PMID 15666341. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ Tidmarsh L, Volkmar FR (2003). "Diagnosis and epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Can J Psychiatry. 48 (8): 517–25. PMID 14574827.

- ↑ Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M (2004). "Adult outcome for children with autism". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 45 (2): 212–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. PMID 14982237.

- ↑ Billstedt E, Gillberg C, Gillberg C (2005). "Autism after adolescence: population-based 13- to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood". J Autism Dev Disord. 35 (3): 351–60. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-3302-5. PMID 16119476.

- ↑ Eaves LC, Ho HH (2008). "Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders". J Autism Dev Disord. 38 (4): 739–47. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x. PMID 17764027.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Newschaffer CJ, Croen LA, Daniels J; et al. (2007). "The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Annu Rev Public Health. 28: 235–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287.

- ↑ Fombonne E (2005). "Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 10): 3–8. PMID 16401144.

- ↑ Changes in diagnostic practices:

- ↑ Rutter M (2005). "Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning". Acta Paediatr. 94 (1): 2–15. PMID 15858952.

- ↑

- ↑ Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A (2007). "Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (4): 326–33. PMID 17404128.

- ↑ Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B (2001). "Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder". Nat Rev Genet. 2 (12): 943–55. doi:10.1038/35103559. PMID 11733747.

- ↑ Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E (2007). "Childhood autism and associated comorbidities". Brain Dev. 29 (5): 257–72. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.003. PMID 17084999.

- ↑ Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E (2001). "Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children". JAMA. 285 (24): 3093–9. PMID 11427137.

- ↑ Levisohn PM (2007). "The autism-epilepsy connection". Epilepsia. 48 (Suppl 9): 33–5. PMID 18047599.

- ↑ Wing L (1997). "The history of ideas on autism: legends, myths and reality". Autism. 1 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1177/1362361397011004.

- ↑ Miles M (2005). "Martin Luther and childhood disability in 16th century Germany: what did he write? what did he say?". Independent Living Institute. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Wolff S (2004). "The history of autism". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 13 (4): 201–8. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0363-5. PMID 15365889.

- ↑ Kuhn R; tr. Cahn CH (2004). "Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology". Hist Psychiatry. 15 (3): 361–6. doi:10.1177/0957154X04044603. PMID 15386868. The quote is a translation of Bleuler's 1910 original.

- ↑ Asperger H (1938). "Das psychisch abnormale Kind". Wien Klin Wochenschr (in German). 51: 1314–7.

- ↑ Kanner L (1943). "Autistic disturbances of affective contact". Nerv Child. 2: 217–50. "Reprint". Acta Paedopsychiatr. 35 (4): 100–36. 1968. PMID 4880460. Unknown parameter

|quotes=ignored (help) - ↑ Lyons V, Fitzgerald M (2007). "Asperger (1906–1980) and Kanner (1894–1981), the two pioneers of autism". J Autism Dev Disord. 37 (10): 2022–3. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0383-3. PMID 17922179.

- ↑ Fombonne E (2003). "Modern views of autism". Can J Psychiatry. 48 (8): 503–5. PMID 14574825.

- ↑ Szatmari P, Jones MB (2007). "Genetic epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". In Volkmar FR. Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (2nd ed ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 157–78. ISBN 0521549574.

- ↑ Biever C (2007-06-30). "Web removes social barriers for those with autism". New Scientist (2610).

- ↑ Harmon A (2004-12-20). "How about not 'curing' us, some autistics are pleading". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

Template:Pervasive developmental disorders

ar:توحد bn:আত্মসংবৃতি bs:Autizam bg:Аутизъм ca:Autisme cs:Autismus cy:Awtistiaeth da:Autisme de:Autismus el:Αυτισμός eo:Aŭtismo eu:Autismo fa:اوتیسم ga:Uathachas ko:자폐증 hy:Աուտիզմ hr:Autizam io:Autismo id:Autisme ia:Autismo it:Autismo he:אוטיזם ka:აუტიზმი ku:Otîstîzm la:Autismus lt:Autizmas jbo:ka sezga'o hu:Autizmus ml:ഓട്ടിസം ms:Autisme nl:Autisme no:Autisme sq:Autizmi simple:Autism sk:Autizmus (uzavretosť) fi:Autismi sv:Autism ta:மதியிறுக்கம் uk:Аутизм wa:Otisse