X-linked agammaglobulinemia

| X-linked agammaglobulinemia | |

| ICD-10 | D80.0 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 279.04 |

| OMIM | 300300 |

| DiseasesDB | 1728 |

For patient information, click here

|

X-linked agammaglobulinemia Microchapters |

|

Differentiating X-linked agammaglobulinemia from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

X-linked agammaglobulinemia On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of X-linked agammaglobulinemia |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating X-linked agammaglobulinemia |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for X-linked agammaglobulinemia |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

X-linked agammaglobulinemia (also called X-linked hypogammaglobulinemia, XLA, Bruton type agammaglobulinemia) is a rare X-linked genetic disorder that affects the body's ability to fight infection (origin of the name: A=no, gammaglobulin=Antibody). XLA patients do not generate mature B cells. B cells are part of the immune system and normally manufacture antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) which defends the body from infections (the humoral response). Patients with untreated XLA are prone to develop serious and even fatal infections.[1] Patients typically present in early childhood with recurrent infections, particularly with extracellular, encapsulated bacteria.[2] XLA is an X-linked disorder, and therefore is almost always limited to males. It occurs in a frequency of about 1 in 100,000 male newborns, and has no ethnic predisposition. XLA is treated by infusion of human antibody. Treatment with pooled gamma globulin cannot restore a functional population of B cells, but it is sufficient to reduce the severity and number of infections due to the passive immunity granted by the exogenous antibodies.[2]

XLA is caused by a mutation on the X chromosome of a single gene identified in 1993 and known as Bruton's tyrosine kinase, or Btk.[2] XLA was first characterized by Dr. Ogden Bruton in a ground-breaking research paper published in 1952 describing a boy unable to develop immunities to common childhood diseases and infections. Bruton's paper describes the first known immune deficiency. XLA is classified with other inherited (genetic) defects of the immune system, known as primary immunodeficiency disorders.[3]

Genetics

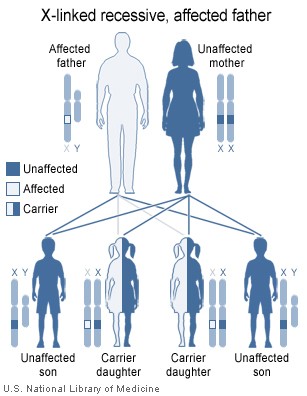

The gene Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) plays an essential role in the maturation B cells in the bone marrow, and when mutated, immature pre-B lymphocytes are unable to develop into mature B cells that leave the bone marrow into the blood stream. The disorder is X-linked (it is on the X chromosome), and is almost entirely limited to the sons of asymptomatic female carriers .[2] This is because males have only one copy of the X chromosome, while females have two copies; one normal copy of an X chromosome can compensate in for mutations in the other X chromosome. Females carriers have a 50% chance of giving birth to a male child with XLA.

An XLA patient will pass on the gene, and all of his daughters will be XLA carriers, meaning that any male grandchildren from an XLA patient's daughters have a 50% chance of inheriting XLA. A female XLA patient can only arise as the child of an XLA patient and a carrier mother. XLA can also rarely result from a spontaneous mutation in the fetus of a non-carrier mother.

|

|

Diagnosis

XLA diagnosis usually begins due to a history of recurrent infections, mostly in the respiratory tract, through childhood. The diagnosis is probable when blood tests show the complete lack of circulating B cells (determined by the B cell marker CD19 and/or CD20), as well as low levels of all antibody classes, including IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE and IgD.[2]

When XLA is suspected, it is possible to do a Western blot test to determine whether the Btk protein is being expressed. Results of a genetic blood test confirm the diagnosis and will identify the specific Btk mutation,[2] however its cost prohibits its use in routine screening for all pregnancies. Women with an XLA patient in their family should seek genetic counseling before pregnancy.

Treatment

The most common treatment for XLA is an intravenous infusion of immunoglobulin (IVIg, human IgG antibodies) every 3-4 weeks, for life. IVIg is a human product extracted and pooled from thousands of blood donations. IVIg does not cure XLA but increases the patient's lifespan and quality of life, by generating passive immunity, and boosting the immune system.[2] With treatment, the number and severity of infections is reduced. With IVIg, XLA patients may a live relatively healthy life. A patient should attempt reaching a state where his IgG blood count exceeds 800 mg/Kg. The dose is based on the patient's weight and IgG blood-count. The dosing rule of thumb is 1g of IVIg for every 2kg of patient's weight.

Muscle injections of immunoglobulin (IMIg) were common before IVIg was prevalent, but are less effective and much more painful, hence, IMIg is now uncommon.

Subcutaneous treatment (SCIg) was recently approved by the FDA, which is recommended in cases of severe adverse reactions to the IVIg treatment.

Antibiotics are another common supplementary treatment. Local antibiotic treatment (drops, lotions) are preferred over systemic treatment (pills) for long term treatment, if possible.

One of the future prospects of XLA treatment is gene therapy, which could potentially cure XLA. Gene therapy technology is still in its infancy and may cause severe complications such as cancer and even death. Moreover, the long term success and complications of this treatment are, as yet, unknown.

Other considerations

Serology (detection on antibodies to a specific pathogen or antigen) is often used to diagnose viral diseases. Because XLA patients lack antibodies, these tests always give a negative result regardless of their real condition. This applies to standard HIV tests. Special blood tests (such as the western blot based test) are required for proper viral diagnosis in XLA patients.

It is not recommended and dangerous for XLA patients to receive live attenuated vaccines such as live polio, or the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR vaccine).[2] Special emphasis is given to avoiding the oral live attenuated SABIN-type polio vaccine that has been reported to cause polio to XLA patients. Furthermore, it is not known if active vaccines in general have any beneficial effect on XLA patients as they lack normal ability to maintain immune memory.

XLA patients are specifically susceptible to viruses of the Enterovirus family, and mostly to: polio virus, coxsackie virus (hand, foot, and mouth disease) and Echoviruses. These may cause severe central nervous system conditions as chronic encephalitis, meningitis and death. An experimental anti-viral agent, pleconaril, is active against picornaviruses. XLA patients, however, are apparently immune to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), as they lack B cells needed for the viral infection.

It is not known if XLA patients are able to generate an allergic reaction, as they lack functional IgE antibodies.

There is no special hazard for XLA patients in dealing with pets or outdoor activities.[2]

Unlike in other primary immunodeficiencies XLA patients are at no greater risk for developing autoimmune illnesses.

Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) is similar to the primary immunodeficiency disorder Hypogammaglobulinemia (CVID), and their clinical conditions and treatment are almost identical. However, while XLA is a congenital disorder, with known genetic causes, CVID may occur in adulthood and its causes are not yet understood.

XLA was also historically mistaken as Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), a much more severe immune deficiency ("Bubble boys").

A strain of laboratory mouse, XID, is used to study XLA. These mice have a mutated version of the mouse Btk gene, and exhibit a similar, yet milder, immune deficiency as in XLA.

See also

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg)

- Hypogammaglobulinemia (CVID)

References

- ↑ XLA information by St. Jude Children's Hospital

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia Patient and Family Handbook for The Primary Immune Diseases. Third Edition. 2001. Published by the Immune Deficiency Foundation

- ↑ Bruton, Ogden C. Agammaglobulinemia

External links

- BTKBASE - Mutation Databse

- XLA patients community

- International Patient Organisation for Primary Immunodeficiencies

- The Immune Deficiency Foundation

- More info

sr:Конгенитална агамаглобулинемија (Брутон) he:XLA de:Agammaglobulinämie