PCI in the patient in cardiogenic shock

| Myocardial infarction | |

| |

|---|---|

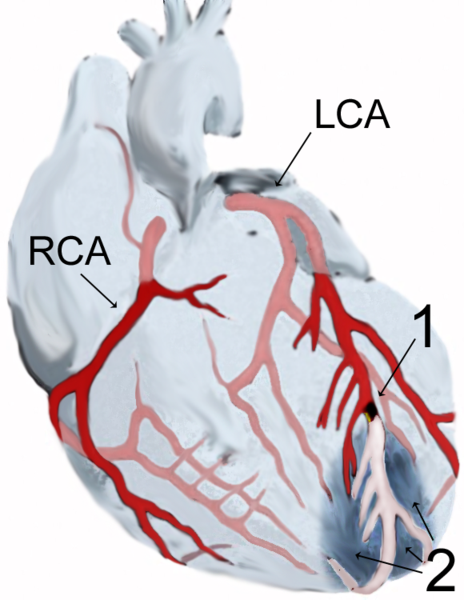

| Diagram of a myocardial infarction (2) of the tip of the anterior wall of the heart (an apical infarct) after occlusion (1) of a branch of the left coronary artery (LCA, right coronary artery = RCA). | |

| ICD-10 | I21-I22 |

| ICD-9 | 410 |

| DiseasesDB | 8664 |

| MedlinePlus | 000195 |

| eMedicine | med/1567 emerg/327 ped/2520 |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss PCI in the patient in cardiogenic shock further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Vijayalakshmi Kunadian MBBS MD MRCP [2];

Definition

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a disorder caused by decreased systemic cardiac output (cardiac index 2.2 L/min/m2 or less) in the presence of adequate intravascular volume, resulting in tissue hypoxia. Shock may be the result of severe left ventricular dysfunction, but it may also occur when left-ventricular function is well preserved. Shock can occur in the setting of mechanical complications such as acute severe mitral regurgitation (8.3%) or ventricular septal rupture (4.6%), right ventricular infarction (3.4%) and prior severe valve disease 1. Other causes of cardiogenic shock include myocarditis, end-stage cardiomyopathy, myocardial contusion, septic shock with severe myocardial depression, myocardial dysfunction after prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

As early as 1912, Herrick described the clinical features of cardiogenic shock in patients with severe coronary artery disease. He noted that patients in CS had a weak, rapid pulse, feeble cardiac tones, pulmonary rales, dyspnea, and cyanosis 2. Systemic hypotension is generally regarded as essential to the diagnosis of the syndrome. There is, however, great variability in the degree of hypotension that defines shock. Commonly, the cut-off point for systolic blood pressure is less than 90 mmHg. Other systemic signs of hypoperfusion such as altered mental state, cold, clammy skin and oliguria are associated with reduction in systolic blood pressure.

Incidence of cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic Shock (CS) is the most common cause of death in the setting of acute myocardial infarction with mortality around 70-80% and this remains almost the same in the last three decades. CS complicates 7-10% of patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and 3% of patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). In the Worcester Heart Attack registry, there was no significant difference in the incidence of CS over a 23 year period. However, the short term survival has increased in recent years since the use of coronary reperfusion strategies 3. In the NRMI (National Registry of Myocardial Infarction) study, the overall in-hospital cardiogenic shock mortality decreased from 60.3% in 1995 to 47.9% in 2004 (p<0.001) 4.

There are differences observed between countries in the management of patients with cardiogenic shock. In the GUSTO I (Global Utilization of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries) trial, Holmes et al demonstrated that aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were used more commonly in the USA than in the other countries: cardiac catheterisation (58% vs. 23%), intra-aortic balloon pump (35% vs. 7%), right heart catheterisation (57% vs. 22%) and ventilatory support (54% vs. 38%). In total, 483 (26%) patients treated in the USA underwent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), compared with 82 (8%) patients in other countries. As a result of these differences in the use of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, there was a significant difference in the 30-day mortality among patients treated in the USA compared to those treated in other countries (50% vs. 66%, p<0.001) 5.

Early and prompt recognition of symptoms and signs of cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction is the most important step for their management. Previous studies suggest that PCI in the setting for cardiogenic shock is not associated with improved mortality at 30 days. However, there is a significant survival benefit at 6 months 6. Therefore once properly diagnosed, these patients should be immediately transferred to a PCI capable and experienced catheterization laboratory for primary PCI. Patients with cardiogenic shock who undergo fibrinolysis or rescue PCI for failed fibrinolysis remain at substantial risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. According to current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a Class I indication for patients <75 years with cardiogenic shock and Class IIa for patients >75 years with cardiogenic shock. Current guidelines also recommend direct or expeditious transfer of patients with cardiogenic shock to hospitals with primary PCI capabilities and favor primary PCI over fibrinolytic therapy for this group of patients 7.

Pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock

The pathophysiology of shock involves a downward spiral: Ischemia causes myocardial dysfunction, which in turn worsens ischemia. When a critical mass of left ventricular myocardium is ischemic or necrotic and fails to pump, stroke volume and cardiac output decrease. Myocardial perfusion is compromised by hypotension and tachycardia which in turn exacerbates ischemia. Fluid retention and impaired diastolic filling caused by tachycardia and ischemia may result in pulmonary congestion and hypoxia. Decreased cardiac output also compromises systemic perfusion, which can lead to lactic acidosis and further compromise of systolic performance. Anaerobic glycolysis also causes accumulation of lactic acid and resultant intracellular acidosis. Apoptosis (programmed cell death) may also contribute to myocyte loss in myocardial infarction.

Myocardial stunning represents persistent post ischemic dysfunction after restoration of normal blood flow. In myocardial stunning, the myocardial performance recovers completely eventually. A combination of oxidative stress, perturbation of calcium homeostasis and decreased myofilament responsiveness to calcium seem to be associated with stunning. Hibernating myocardium is in a state of persistently impaired function at rest because of severely reduced coronary blood flow 8. Stunning and hibernation develop as an adaptive response to hypoperfusion. Both conditions may indicate recovery over time as reperfusion occurs.

New pathogenic insights

In the SHOCK (SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded coronaries for Cardiogenic shocK) trial and registry, wide range of ejection fractions and left ventricular sizes were noted. The systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was not elevated on vasopressors with a wide range of SVR measured. A clinically evident systemic inflammatory response syndrome was often present in patients with CS. Most survivors had class I congestive heart failure (CHF) status 9. Cardiac power, the product of cardiac index and mean arterial pressure was strongly associated with mortality. The ability to raise SVR may be an important compensatory mechanism to support blood pressure. Vasodilators (endogenous and exogenous) interfere with the critical compensatory vasoconstriction mechanism in response to a reduction in cardiac output. The classic notion that CS develops when 40% of the left ventricle (LV) is irreversibly damaged is inconsistent with the observations in the SHOCK studies. In the SHOCK studies, 50% of patients survive and there is improved ejection fraction following revascularization. Following shock, 58% of patients are in New York Heart Association CHF class I 10. The range of LVEFs, LV size and SVR in patients with cardiogenic shock would indicate that the pathogenesis is multifactorial.

Treatment strategies

Initial management of patients with CS includes fluid resuscitation unless pulmonary edema is present. In patients with inadequate tissue perfusion and adequate intravascular volume, cardiovascular support with inotropic agent should be initiated. Catecholamine infusions must be carefully titrated to maximize coronary perfusion pressure. The phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as amrinone and milrinone have positive inotropic and vasodilatory actions. Diuretics should be used to treat patients with pulmonary edema and enhance oxygenation.

No trials have demonstrated that thrombolytic therapy reduces mortality rates in patients with established CS. In the GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico) trial, 30-day moratlity was 69.9% and 70.1% among those who received streptokinase and placebo respectively 11. In the GUSTO trial, mortality was 56% and 59% among those who received Streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator respectively in the setting of CS 12.

Impact of angioplasty, stenting and abciximab on survival

A number of retrospective studies have demonstrated that PCI in the setting of CS is associated with improved outcomes. In the SHOCK trial registry, not only was the mortality rate lower in patients selected for cardiac catheterization (51%) than in those not selected (85%), but the mortality rate was also lower in catheterized patients who did not undergo revascularization (58%). In the SHOCK randomized trial, the 30-day mortality rate was 46.7% in the early intervention group and 56% in the initial medical therapy group. At 6 months there was 12% absolute risk reduction using the intervention strategy. Subgroup analysis demonstrated substantial improvement in mortality rates in patients younger than 75 years of age at 30 days (41% intervention vs. 57% medical therapy) and at 6 months (48% vs. 69% respectively).

Stenting and the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been studied in the setting of cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. A previous study by Chan et al demonstrated that the use of stent and abciximab in patients with cardiogenic shock was associated with greater achievement of TIMI 3 flow and significant improvement in mortality compared to stent only, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) plus abciximab, and PTCA alone [33%, 43%, 61%, and 68%, respectively (log-rank p<0.028)]. TIMI grade 3 flow was higher with stent plus abciximab than with the other interventions (85% vs. 65%, p<0.048) 13. This was confirmed in another study where patients who underwent stenting plus abciximab did significantly better in the short and long term 14.

PCI in specific subsets

Gender differences

In the SHOCK trial after adjusting for patient demographics and treatment strategies, there was no difference in in-hospital mortality between men and women (odds ratio = 1.03, 95% confidence interval of 0.73 to 1.43, p = 0.88). Mortality was also similar for women and men who were selected for revascularization (44% vs. 38%, p=0.244). But women encountered more mechanical complications such as mechanical ventricular rupture and acute severe mitral regurgitation. Women also had higher incidence of hypertension, diabetes and lower cardiac index 15.

Diabetic patients

Cardiogenic shock develops approximately twice as often among diabetics (10.6%) as among non diabetic patients (6.2%) with acute MI. The prognosis of diabetics with cardiogenic shock is similar to the prognosis of non diabetic patients with cardiogenic shock 16. Among patients with STEMI and CS and without a prior diagnosis of diabetes undergoing primary PCI, admission glucose concentration is a very strong independent predictor for 1-year mortality. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the odds for mortality increased by 16% for every 1 mmol/L increase in plasma glucose concentration (OR 1.155, 95% CI 1.070-1.247), after adjustment for left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, age older than 75 years, male sex and TIMI 3 flow after PCI 17.

Elderly patients

Patients in cardiogenic shock aged ≥75 years are associated with increased 30-day mortality (75%) compared to those aged <75 years (41.4%) in the PCI group in a sub analysis from the SHOCK trial. In the medical therapy group, 30-day mortality was 53.1% for those aged ≥75 years and 56.8% for patients aged <75 years 18. Another study demonstrated that 56% of patients survived to be discharged from the hospital and of the hospital survivors, 75% were alive at 1 year 19. A registry study from northern New England demonstrated that mortality rate for patients over 75 years of age was 46% which is significantly less than that reported in the randomized trials 20.

Among patients with multivessel disease, CS is especially frequent in those with anterior STEMI, female gender, proximal culprit lesion, and chronic occlusion of other vessels 21.

PCI for failed fibrinolysis

PCI for failed fibrinolysis in the setting of CS has been studied. Rescue PCI in patients with CS is associated with poor outcome compared to those who undergo primary PCI particularly in those patients aged > 70 years of age. A previous study demonstrated that rescue PCI, anterior myocardial infarction, multivessel disease and lower final TIMI 3 flow in patients with cardiogenic shock were an independent predictor of 30-day mortality in patients undergoing rescue PCI. In patients aged >70 years, the one year mortality was 100% in those who underwent rescue PCI compared to 70% in those who underwent primary PCI 22. Hence rescue PCI in patients aged >70 years may be a futile treatment.

Adjunct therapies

L-NG monomethyl-arginine

CS complicating acute myocardial infarction is often simply not only due to extensive infarction and ischemia with reduced ventricular function but also involves inflammatory mediators. These mediators increase nitric oxide and peroxynitrite levels, resulting in further myocardial dysfunction and failure of an appropriate peripheral circulatory response. Cotter et al assessed the safety and efficacy of L-NMMA (L-NG monomethyl-arginine), a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, in the treatment of cardiogenic shock 23. In 11 consecutive patients, within 10 minutes of L-NMMA administration, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) increased from 76±9 to 109±22 mmHg (+43%). Urine output increased within 5 hours from 63±25 to 156±63 cc/h (+148%). Cardiac index decreased during the steep increase in MAP from 2.0±0.5 to 1.7±0.4 L/(min.m2) (-15%); however, it gradually increased to 1.85±0.4 L/(min.m2) after 5 hours. The heart rate and the wedge pressure remained stable. Twenty-four hours after L-NMMA discontinuation, MAP (+36%) and urine output (+189%) remained increased; however, cardiac index returned to pretreatment level. No adverse events were detected. Ten out of eleven patients were weaned off mechanical ventilation and IABP. Eight patients were discharged from the coronary intensive care unit, and seven (64%) were alive at 1-month follow-up.

Levosimendan

The effect of levosimendan (a positive inotropic agent) on long-term survival was compared to dobutamine treatment in patients with STEMI revascularized by primary coronary angioplasty who subsequently developed CS. This demonstrated that levosimendan compared to dobutamine did not improve long-term survival in this group of patients 24. However, levosimendan seems to be effective in improving the Doppler echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular diastolic function in patients with STEMI revascularized by primary PCI who developed cardiogenic shock 25.

Intra-aortic balloon pump

The intra aortic balloon pump (IABP) is the most commonly used temporary cardiac assist device. It has immediate beneficial haemodynamic effects, augmenting coronary perfusion, increasing myocardial oxygen supply and decreasing myocardial oxygen demand. In the setting of acute myocardial infarction, left ventricular unloading by an IABP could prevent early infarct expansion, ventricular remodeling, or both 26.

Although used widely in the setting of cardiogenic shock 27-31, the use of aortic counter pulsation in non-shocked but high risk patients remains uncertain. Prolonged use of intra aortic balloon pump (IABP) can be beneficial in patients with CS in terms of improvement in left ventricular function and exercise capacity. In the SHOCK trial registry, patients who received a fibrinolytic and had intra aortic balloon pump support had reduced mortality compared to those who had IABP alone, fibrinolytic alone, and no fibrinolytic and IABP groups (47%, 52%, 63%, 77% respectively) 30.

Several studies in critically ill patients suggest that an IABP may be beneficial in those with impaired coronary arterial auto-regulation 32. However, in the setting of a fixed, severe coronary arterial stenosis (>90% luminal diameter narrowing), the IABP-induced increase in aortic diastolic pressure is not transmitted to the vessel’s post stenotic segment; as a result, post stenotic coronary blood flow is unchanged 32, but can increase flow once the stenosis has been treated by angioplasty. In hospitals without primary PCI capability, stabilization with IABP and thrombolysis followed by transfer to a tertiary care facility may be the best management option.

Left ventricular assist devices

Left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) can be used more effectively to reverse the haemodynamic and metabolic parameters than by the use of IABP. The use of LVAD is however associated with more complications including major bleeding. A previous study demonstrated no difference in 30-day mortality with the use of LVAD and IABP 33.

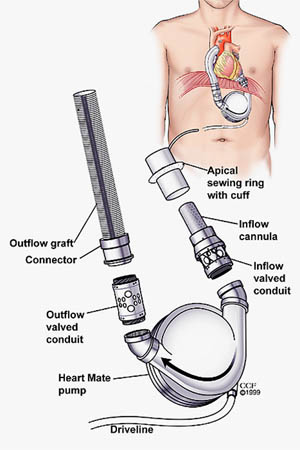

The LVADS are commonly used as a bridge to cardiac transplantation and bridge to recovery in patients with chronic heart failure. It has also been used in high risk PCI. A study by Giombolini et al demonstrated that left ventricular assist device can be easily and rapidly deployed either in emergency or in elective high-risk PCI to achieve complete cardiac assistance 34. There are three generations of LVADs currently available based on the order they were developed and the type of pumping mechanisms used. The HeartMate® I (Thermo Cardiosystems Inc., Woburn, MA) is the first generation device that uses pusher plates and has inflow and outflow valves. These devices are efficacious at unloading the left ventricle and maintaining the circulation, with the capacity to pump up to 10 litres/min. The disadvantages of these pulsatile devices include their large size. The complexity of their insertion can result in infection and compression of neighboring organs. Because these devices contain valves, they are not long lasting.

The second-generation LVADs are continuous-flow impeller pumps. These are considerably smaller and safer to insert. They have only one moving part (the rotor) and are expected to have greater durability than first-generation devices. Furthermore, the use of these pumps requires full anticoagulant therapy to maintain an international normalized ratio of 2.0–2.5, coupled with antiplatelet medication, such as aspirin or clopidogrel. Experience with these devices is increasing and data from the first series of patients to receive the HeartMate II® (Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA) have now been published 35. In a prospective, multicenter study without a concurrent control group, 133 patients with end-stage heart failure who were on a waiting list for heart transplantation underwent implantation of HeartMate II. The principal outcomes occurred in 100 patients (75%). The median duration of support was 126 days (range, 1 to 600). The survival rate during support was 75% at 6 months and 68% at 12 months. At 3 months, therapy was associated with significant improvement in functional status (according to the New York Heart Association class and results of a 6-minute walk test) and in quality of life (according to the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaires). Major adverse events included postoperative bleeding, stroke, right heart failure, and percutaneous lead infection. Pump thrombosis occurred in two patients. In October 2008 Thoratec Corp. recalled "small batches" of HeartMate II pumps following the deaths of five patients who had the implant. The five deaths occurred when physicians were unable to replace devices with worn electrical wire. Thoratec Corp. has confirmed 27 total instances where HeartMate II implants have needed replacement due to the wiring issue.[1]

Several third generation devices are now being studied in phase I studies such as involving the Ventrassist® (Ventracor Ltd, Chatswood, Australia) and HVAD® (HeartWare, Miramar, FL) devices, and more recently the DuraHeart® (Terumo Kabushiki Kaisha [Terumo Corporation] Shibuya-ku, Japan) system. The current third generation pumps are thought to last approximately 5 years.

Predictors of outcome following PCI

Various baseline and angiographic factors determine the outcome of patients in cardiogenic shock undergoing PCI. In the SHOCK trial, the independent correlates of mortality were as follows: increasing age (p<0.001), lower systolic blood pressure (p<0.009), increasing time from randomization to PCI (p<0.019), lower post-PCI TIMI flow (0/1 vs. 2/3) (p<0.001), and multivessel PCI (p<0.040) 36. Other studies confirm these observations 37. Another study demonstrated that elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) on admission was associated with increased 1-year mortality (p=0.002) 38. Patients with myocardial blush grade 0/1 following PCI were associated with significantly elevated in-hospital (81% vs. 14%) and long term (81% vs. 29%) mortality compared to those with MBG 2/3 respectively 39.

Functional state and quality of life post PCI

Although the one year mortality following PCI in the setting of cardiogenic shock is still high at 54%, patients who survive have good functional status. Follow-up of patients in the SHOCK trial demonstrated that patients who underwent PCI had lower rate of functional deterioration than those who underwent medical therapy for cardiogenic shock. At one year, 83% of patients discharged alive after an initial hospitalization for cardiogenic shock were in NYHA functional class I or II. In particular, patients who underwent early revascularization had better mental health immediately after discharge and were protected against deterioration in their functional status over time. Moreover, survivors of early revascularization after shock can have recovery of physical function similar to that of patients with elective revascularization 40.

PCI vs. CABG in cardiogenic shock

In the SHOCK (SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded coronaries for Cardiogenic shocK) trial 63.3% of patients underwent PCI and 36.7% underwent coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). There were more diabetics (48.9% vs. 26.9%; p=0.02), 3-vessel disease (80.4% vs. 60.3%; p=0.03), and left main coronary disease (41.3% vs. 13.0%; p=0.001) in the CABG group compared to the PCI group. In the PCI group, 12.3% had 2-vessel and 2.5% had 3-vessel interventions. The survival rates were 55.6% in the PCI group compared with 57.4% in the CABG group at 30 days (p=0.86) and 51.9% compared with 46.8% respectively at 1 year (p=0.71) 41. Although there was no significant difference in the mortality in the two groups, patients with extensive coronary artery disease complicated by cardiogenic shock should be considered for CABG.

Conclusion

Cardiogenic shock following an acute myocardial infarction is associated with high mortality rates (50-80%). The key to a good outcome is an organized approach with rapid diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapy to maintain blood pressure and improve cardiac output. Expeditious coronary revascularization is crucial. Although there was a general increase in the rate of primary PCI for CS over time that was associated with an improved survival, there was no temporal impact of the ACC guidelines for the management of CS in clinical practice. PCI and CABG were still underused in the NRMI registry, potentially due to the higher mortality rates that are seen in patients with CS. PCI may be more liberally used in the elderly.

Reference List

- Hochman JS, Boland J, Sleeper LA, Porway M, Brinker J, Col J, Jacobs A, Slater J, Miller D, Wasserman H, . Current spectrum of cardiogenic shock and effect of early revascularization on mortality. Results of an International Registry. SHOCK Registry Investigators. Circulation 1995 February 1;91(3):873-881.

- Herricks B. Clinical features of sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries. JAMA 1912;39:2015-2020.

- Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, Gurwitz J, Bigelow C, Gore JM. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1999 April 15;340(15):1162-1168.

- Babaev A, Frederick PD, Pasta DJ, Every N, Sichrovsky T, Hochman JS. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA 2005 July 27;294(4):448-454.

- Holmes DR, Jr., Califf RM, Van de WF, Berger PB, Bates ER, Simoons ML, White HD, Thompson TD, Topol EJ. Difference in countries' use of resources and clinical outcome for patients with cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO trial. Lancet 1997 January 11;349(9045):75-78.

- Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, Buller CE, Jacobs AK, Slater JN, Col J, McKinlay SM, LeJemtel TH. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med 1999 August 26;341(9):625-634.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC, Jr., Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004 August 3;110(5):588-636.

- Hollenberg SM, Kavinsky CJ, Parrillo JE. Cardiogenic shock. Ann Intern Med 1999 July 6;131(1):47-59.

- Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: expanding the paradigm. Circulation 2003 June 24;107(24):2998-3002.

- Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: expanding the paradigm. Circulation 2003 June 24;107(24):2998-3002.

- Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI). Lancet 1986 February 22;1(8478):397-402.

- The effects of tissue plasminogen activator, streptokinase, or both on coronary-artery patency, ventricular function, and survival after acute myocardial infarction. The GUSTO Angiographic Investigators. N Engl J Med 1993 November 25;329(22):1615-1622.

- Chan AW, Chew DP, Bhatt DL, Moliterno DJ, Topol EJ, Ellis SG. Long-term mortality benefit with the combination of stents and abciximab for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2002 January 15;89(2):132-136.

- Huang R, Sacks J, Thai H, Goldman S, Morrison DA, Barbiere C, Ohm J. Impact of stents and abciximab on survival from cardiogenic shock treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005 May;65(1):25-33.

- Wong SC, Sleeper LA, Monrad ES, Menegus MA, Palazzo A, Dzavik V, Jacobs A, Jiang X, Hochman JS. Absence of gender differences in clinical outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. A report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001 November 1;38(5):1395-1401.

- Lindholm MG, Boesgaard S, Torp-Pedersen C, Kober L. Diabetes mellitus and cardiogenic shock in acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail 2005 August;7(5):834-839.

- Vis MM, Sjauw KD, van der Schaaf RJ, Baan J, Jr., Koch KT, DeVries JH, Tijssen JG, de Winter RJ, Piek JJ, Henriques JP. In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock treated with percutaneous coronary intervention, admission glucose level is a strong independent predictor for 1-year mortality in patients without a prior diagnosis of diabetes. Am Heart J 2007 December;154(6):1184-1190.

- Dzavik V, Sleeper LA, Picard MH, Sanborn TA, Lowe AM, Gin K, Saucedo J, Webb JG, Menon V, Slater JN, Hochman JS. Outcome of patients aged >or=75 years in the SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK (SHOCK) trial: do elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock respond differently to emergent revascularization? Am Heart J 2005 June;149(6):1128-1134.

- Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Rihal CS, Berger PB, Holmes DR, Jr. Outcomes of elderly patients with cardiogenic shock treated with early percutaneous revascularization. Am Heart J 2004 June;147(6):1066-1070.

- Dauerman HL, Ryan TJ, Jr., Piper WD, Kellett MA, Shubrooks SJ, Robb JF, Hearne MJ, Watkins MW, Hettleman BD, Silver MT, Niles NW, Malenka DJ. Outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention among elderly patients in cardiogenic shock: a multicenter, decade-long experience. J Invasive Cardiol 2003 July;15(7):380-384.

- Conde-Vela C, Moreno R, Hernandez R, Perez-Vizcayno MJ, Alfonso F, Escaned J, Sabate M, Banuelos C, Macaya C. Cardiogenic shock at admission in patients with multivessel disease and acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: Related factors. Int J Cardiol 2007 December 15;123(1):29-33.

- Kunadian B, Vijayalakshmi K, Dunning J, Thornley AR, Sutton AG, Muir DF, Wright RA, Hall JA, de Belder MA. Should patients in cardiogenic shock undergo rescue angioplasty after failed fibrinolysis: comparison of primary versus rescue angioplasty in cardiogenic shock patients. J Invasive Cardiol 2007 May;19(5):217-223.

- Cotter G, Kaluski E, Blatt A, Milovanov O, Moshkovitz Y, Zaidenstein R, Salah A, Alon D, Michovitz Y, Metzger M, Vered Z, Golik A. L-NMMA (a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor) is effective in the treatment of cardiogenic shock. Circulation 2000 March 28;101(12):1358-1361.

- Samimi-Fard S, Garcia-Gonzalez MJ, Dominguez-Rodriguez A, breu-Gonzalez P. Effects of levosimendan versus dobutamine on long-term survival of patients with cardiogenic shock after primary coronary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 2007 July 20.

- Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Samimi-Fard S, Garcia-Gonzalez MJ, breu-Gonzalez P. Effects of levosimendan versus dobutamine on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with cardiogenic shock after primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 2007 July 20.

- Trost JC, Hillis LD. Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation. The American Journal of Cardiology 2006 May 1;97(9):1391-1398.

- Cohen M, Urban P, Christenson JT, Joseph DL, Freedman RJ, Jr., Miller MF, Ohman EM, Reddy RC, Stone GW, Ferguson JJ, III. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in US and non-US centres: results of the Benchmark Registry. Eur Heart J 2003 October;24(19):1763-1770.

- Stone GW, Ohman EM, Miller MF, Joseph DL, Christenson JT, Cohen M, Urban PM, Reddy RC, Freedman RJ, Staman KL, Ferguson JJ, III. Contemporary utilization and outcomes of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction: the benchmark registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003 June 4;41(11):1940-1945.

- Weiss AT, Engel S, Gotsman CJ, Shefer A, Hasin Y, Bitran D, Gotsman MS. Regional and global left ventricular function during intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in patients with acute myocardial infarction shock. American Heart Journal 1984 August;108(2):249-254.

- Sanborn TA, Sleeper LA, Bates ER, Jacobs AK, Boland J, French JK, Dens J, Dzavik V, Palmeri ST, Webb JG, Goldberger M, Hochman JS. Impact of thrombolysis, intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation, and their combination in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol 2000 September;36(3 Suppl A):1123-1129.

- Barron HV, Every NR, Parsons LS, Angeja B, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Chou TM. The use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: Data from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. American Heart Journal 2001 June;141(6):933-939.

- Kern M, Aguirre F, Tatineni S, Penick D, Serota H, Donohue T, Walter K. Enhanced coronary blood flow velocity during intraaortic balloon counterpulsation in critically ill patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1993;21:359-68.

- Thiele H, Sick P, Boudriot E, Diederich KW, Hambrecht R, Niebauer J, Schuler G. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J 2005 July;26(13):1276-1283.

- Giombolini C, Notaristefano S, Santucci S, Fortunati F, Savino K, Sindaco FD, Ragni T, Allegri M, Ambrosio G. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device, TandemHeart, for high-risk percutaneous coronary revascularization. A single centre experience. Acute Card Care 2006;8(1):35-40.

- Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Boyle AJ, Aaronson KD, Conte JV, Naka Y, Mancini D, Delgado RM, MacGillivray TE, Farrar DJ, Frazier OH. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med 2007 August 30;357(9):885-896.

- Webb JG, Lowe AM, Sanborn TA, White HD, Sleeper LA, Carere RG, Buller CE, Wong SC, Boland J, Dzavik V, Porway M, Pate G, Bergman G, Hochman JS. Percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock in the SHOCK trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003 October 15;42(8):1380-1386.

- Zeymer U, Vogt A, Zahn R, Weber MA, Tebbe U, Gottwik M, Bonzel T, Senges J, Neuhaus KL. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in 1333 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); Results of the primary PCI registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Eur Heart J 2004 February;25(4):322-328.

- Lim SY, Jeong MH, Bae EH, Kim W, Kim JH, Hong YJ, Park HW, Kang DG, Lee YS, Kim KH, Lee SH, Yun KH, Hong SN, Cho JG, Ahn YK, Park JC, Ahn BH, Kim SH, Kang JC. Predictive factors of major adverse cardiac events in acute myocardial infarction patients complicated by cardiogenic shock undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ J 2005 February;69(2):154-158.

- Tarantini G, Ramondo A, Napodano M, Bilato C, Isabella G, Razzolini R, Iliceto S. Myocardial perfusion grade and survival after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in patients with cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol 2004 May 1;93(9):1081-1085.

- Sleeper LA, Ramanathan K, Picard MH, Lejemtel TH, White HD, Dzavik V, Tormey D, Avis NE, Hochman JS. Functional status and quality of life after emergency revascularization for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005 July 19;46(2):266-273.

- White HD, Assmann SF, Sanborn TA, Jacobs AK, Webb JG, Sleeper LA, Wong CK, Stewart JT, Aylward PE, Wong SC, Hochman JS. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) trial. Circulation 2005 September 27;112(13):1992-2001.