Mifepristone

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Alberto Plate [2]

Disclaimer

WikiDoc MAKES NO GUARANTEE OF VALIDITY. WikiDoc is not a professional health care provider, nor is it a suitable replacement for a licensed healthcare provider. WikiDoc is intended to be an educational tool, not a tool for any form of healthcare delivery. The educational content on WikiDoc drug pages is based upon the FDA package insert, National Library of Medicine content and practice guidelines / consensus statements. WikiDoc does not promote the administration of any medication or device that is not consistent with its labeling. Please read our full disclaimer here.

Black Box Warning

|

TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY

See full prescribing information for complete Boxed Warning.

Mifepristone is a potent antagonist of progesterone and cortisol via the progesterone and glucocorticoid (GR-II) receptors, respectively. The antiprogestational effects will result in the termination of pregnancy. Pregnancy must therefore be excluded before the initiation of treatment with Korlym and prevented during treatment and for one month after stopping treatment by the use of a non-hormonal medically acceptable method of contraception unless the patient has had a surgical sterilization, in which case no additional contraception is needed. Pregnancy must also be excluded if treatment is interrupted for more than 14 days in females of reproductive potential.: (Content)

|

Overview

Mifepristone is an antagonist of progesterone and cortisol receptors that is FDA approved for the treatment of Cushing's syndrome. There is a Black Box Warning for this drug as shown here. Common adverse reactions include hypertension, peripheral edema, hypokalemia, abdominal pain, decreased apetite, diarrhea, nauseas, vomiting, dizziness, headache, abnormal vaginal bleeding, uterine cramps, hypertrophic endometrial disorder and fatigue.

Adult Indications and Dosage

FDA-Labeled Indications and Dosage (Adult)

Hyperglycemia Secondary to Hypercortisolism in Patients with Cushing's Syndrome and Diabetes Mellitus Type-II

- Dosage: 300 mg PO / day taken with meals.

- Maximun dose: 1200 mg/day or 20 mg/kg PO.

- Increases in dose should not occur more frequently than once every 2-4 weeks.

Changes in glucose control, anti-diabetic medication requirements, insulin levels, and psychiatric symptoms may provide an early assessment of response (within 6 weeks) and may help guide early dose titration. Improvements in cushingoid appearance, acne, hirsutism, striae, and body weight occur over a longer period of time and, along with measures of glucose control, may be used to determine dose changes beyond the first 2 months of therapy. Careful and gradual titration of Korlym accompanied by monitoring for recognized adverse reactions may reduce the risk of severe adverse reactions. Dose reduction or even dose discontinuation may be needed in some clinical situations. If Korlym treatment is interrupted, it should be reinitiated at the lowest dose (300 mg). If treatment was interrupted because of adverse reactions, the titration should aim for a dose lower than the one that resulted in treatment interruption.

Off-Label Use and Dosage (Adult)

Guideline-Supported Use

There is limited information regarding Off-Label Guideline-Supported Use of Mifepristone in adult patients.

Non–Guideline-Supported Use

Dilation of Cervical Canal

- Dosage: 600 mg PO[1].

- Administered 48 hours before procedures which need cervical canal dilation.

Emergency Contraception - Postcoital Contraception

- Dosage:

- 10 mg PO: Emergency contraception during the first 120 hours of a single unprotected sexual intercourse.

- 25 mg PO: Emergency contraception during the first 120 hours of a single unprotected sexual intercourse.

- Both doses prove to have the same efficacy[2].

- 600 mg: Emergency contraception during the first 120 hours of a single unprotected sexual intercourse[3]. In two clinical trials, 600 mg Mifepristone demonstrated to be 100% effective in emergency contraception during the first 120 hours of a single unprotected sexual intercourse[4].

Irregular Periods

- Dosage: 50 mg PO once every 4 weeks[5].

Miscarriage

- Dosage

Refractory Ovarian Cancer

- Dosage: 200 mg/day PO[9].

Uterine leiomyoma

- Dosage: 5 mg PO daily[10].

Pediatric Indications and Dosage

FDA-Labeled Indications and Dosage (Pediatric)

Hyperglycemia Secondary to Hypercortisolism in Patients with Cushing's Syndrome and Diabetes Mellitus Type-II

- Dosage: 300 mg PO / day taken with meals.

- Maximun dose: 1200 mg/day or 20 mg/kg PO.

- Increases in dose should not occur more frequently than once every 2-4 weeks.

Changes in glucose control, anti-diabetic medication requirements, insulin levels, and psychiatric symptoms may provide an early assessment of response (within 6 weeks) and may help guide early dose titration. Improvements in cushingoid appearance, acne, hirsutism, striae, and body weight occur over a longer period of time and, along with measures of glucose control, may be used to determine dose changes beyond the first 2 months of therapy. Careful and gradual titration of Korlym accompanied by monitoring for recognized adverse reactions may reduce the risk of severe adverse reactions. Dose reduction or even dose discontinuation may be needed in some clinical situations. If Korlym treatment is interrupted, it should be reinitiated at the lowest dose (300 mg). If treatment was interrupted because of adverse reactions, the titration should aim for a dose lower than the one that resulted in treatment interruption.

Off-Label Use and Dosage (Pediatric)

Guideline-Supported Use

There is limited information regarding Off-Label Guideline-Supported Use of Mifepristone in pediatric patients.

Non–Guideline-Supported Use

There is limited information regarding Off-Label Non–Guideline-Supported Use of Mifepristone in pediatric patients.

Contraindications

Pregnancy

Korlym is contraindicated in women who are pregnant. Pregnancy must be excluded before the initiation of treatment with Korlym or if treatment is interrupted for more than 14 days in females of reproductive potential. Nonhormonal contraceptives should be used during and one month after stopping treatment in all women of reproductive potential. [See Use in Specific Populations 8.8]

Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A

Korlym is contraindicated in patients taking simvastatin, lovastatin, and CYP3A substrates with narrow therapeutic ranges, such as cyclosporine, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, fentanyl, pimozide, quinidine, sirolimus, and tacrolimus, due to an increased risk of adverse events. [See Drug Interactions (7.1) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]

Corticosteroid Therapy Required for Lifesaving Purposes

Korlym is contraindicated in patients who require concomitant treatment with systemic corticosteroids for serious medical conditions or illnesses (e.g., immunosuppression after organ transplantation) because Korlym antagonizes the effect of glucocorticoids.

=====Women with Risk of Vaginal Bleeding or Endometrial Changes Korlym is contraindicated in the following:=====

- Women with a history of unexplained vaginal bleeding

- Women with endometrial hyperplasia with atypia or endometrial carcinoma

Known Hypersensitivity to Mifepristone

Korlym is contraindicated in patients with prior hypersensitivity reactions to mifepristone or to any of the product components.

Warnings

|

TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY

See full prescribing information for complete Boxed Warning.

Mifepristone is a potent antagonist of progesterone and cortisol via the progesterone and glucocorticoid (GR-II) receptors, respectively. The antiprogestational effects will result in the termination of pregnancy. Pregnancy must therefore be excluded before the initiation of treatment with Korlym and prevented during treatment and for one month after stopping treatment by the use of a non-hormonal medically acceptable method of contraception unless the patient has had a surgical sterilization, in which case no additional contraception is needed. Pregnancy must also be excluded if treatment is interrupted for more than 14 days in females of reproductive potential.: (Content)

|

Adrenal Insufficiency

Patients receiving mifepristone may experience adrenal insufficiency. Because serum cortisol levels remain elevated and may even increase during treatment with Korlym, serum cortisol levels do not provide an accurate assessment of hypoadrenalism in patients receiving Korlym. Patients should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, including weakness, nausea, increased fatigue, hypotension, and hypoglycemia. If adrenal insufficiency is suspected, discontinue treatment with Korlym immediately and administer glucocorticoids without delay. High doses of supplemental glucocorticoids may be needed to overcome the glucocorticoid receptor blockade produced by mifepristone. Factors considered in deciding on the duration of glucocorticoid treatment should include the long half-life of mifepristone (85 hours).

Treatment with Korlym at a lower dose can be resumed after resolution of adrenal insufficiency. Patients should also be evaluated for precipitating causes of hypoadrenalism (infection, trauma, etc.).

Hypokalemia

In a study of patients with Cushing's syndrome, hypokalemia was observed in 44% of subjects during treatment with Korlym. Hypokalemia should be corrected prior to initiating Korlym. During Korlym administration, serum potassium should be measured 1 to 2 weeks after starting or increasing the dose of Korlym and periodically thereafter. Hypokalemia can occur at any time during Korlym treatment. Mifepristone-induced hypokalemia should be treated with intravenous or oral potassium supplementation based on event severity. If hypokalemia persists in spite of potassium supplementation, consider adding mineralocorticoid antagonists.

Vaginal Bleeding and Endometrial Changes

Being an antagonist of the progesterone receptor, mifepristone promotes unopposed endometrial proliferation that may result in endometrium thickening, cystic dilatation of endometrial glands, and vaginal bleeding. Korlym should be used with caution in women who have hemorrhagic disorders or are receiving concurrent anticoagulant therapy. Women who experience vaginal bleeding during Korlym treatment should be referred to a gynecologist for further evaluation.

QT Interval Prolongation

Mifepristone and its metabolites block IKr. Korlym prolongs the QTc interval in a dose-related manner. There is little or no experience with high exposure, concomitant dosing with other QT-prolonging drugs, or potassium channel variants resulting in a long QT interval. To minimize risk, the lowest effective dose should always be used.

Exacerbation/Deterioration of Conditions Treated with Corticosteroids

Use of Korlym in patients who receive corticosteroids for other conditions (e.g., autoimmune disorders) may lead to exacerbation or deterioration of such conditions, as Korlym antagonizes the desired effects of glucocorticoid in these clinical settings. For medical conditions in which chronic corticosteroid therapy is lifesaving (e.g., immunosuppression in organ transplantation), Korlym is contraindicated.

Use of Strong CYP3A Inhibitors

Korlym should be used with extreme caution in patients taking ketoconazole and other strong inhibitors of CYP3A, such as itraconazole, nefazodone, ritonavir, nelfinavir, indinavir, atazanavir, amprenavir, fosamprenavir, boceprevir, clarithromycin, conivaptan, lopinavir, posaconazole, saquinavir, telaprevir, telithromycin, or voriconazole, as these could substantially increase the concentration of mifepristone in the blood. The benefit of concomitant use of these agents should be carefully weighed against the potential risks. Mifepristone should be used in combination with strong CYP3A inhibitors only when necessary, and in such cases the dose should be limited to 300 mg per day.

Pneumocystis jiroveci Infection

Patients with endogenous Cushing's syndrome are at risk for opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia during Korlym treatment. Patients may present with respiratory distress shortly after initiation of Korlym. Appropriate diagnostic tests should be undertaken and treatment for Pneumocystis jiroveci should be considered.

Potential Effects of Hypercortisolemia

Korlym does not reduce serum cortisol levels. Elevated cortisol levels may activate mineralocorticoid receptors which are also expressed in cardiac tissues. Caution should be used in patients with underlying heart conditions including heart failure and coronary vascular disease.

Adverse Reactions

Clinical Trials Experience

Gastrointestinal Effects

General Effects

Central Nervous System Effects

Musculoeskeletal Effects

Laboratory Findings

- Hypokalemia

- Abnormal thyroid function test (High TSH levels)

- Reduction of HDL-C serum levels

Infectious and Infestations

Metabolism and Nutritional Effects

- Decreased appetite

- Anorexia

Vascular Disorder

Reproductive system and Breast Disorders

Respiratory Effects

Psychiatric Disorders

Postmarketing Experience

There is limited information regarding Mifepristone Postmarketing Experience in the drug label.

Drug Interactions

Based on the long terminal half-life of mifepristone after reaching steady state, at least 2 weeks should elapse after cessation of Korlym before initiating or increasing the dose of any interacting concomitant medication.

Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A

Because Korlym is an inhibitor of CYP3A, concurrent use of Korlym with a drug whose metabolism is largely or solely mediated by CYP3A is likely to result in increased plasma concentrations of the drug. Discontinuation or dose reduction of such medications may be necessary with Korlym co-administration.

Korlym increased the exposure to simvastatin and simvastatin acid significantly in healthy subjects. Concomitant use of simvastatin or lovastatin is contraindicated because of the increased risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

The exposure of other substrates of CYP3A with narrow therapeutic ranges, such as cyclosporine, dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, fentanyl, pimozide, quinidine, sirolimus, and tacrolimus, may be increased by concomitant administration with Korlym. Therefore, the concomitant use of such CYP3A substrates with Korlym is contraindicated. [See Contraindications (4.2)]

Other drugs with similar high first pass metabolism in which CYP3A is the primary route of metabolism should be used with extreme caution if co-administered with Korlym. The lowest possible dose and/or a decreased frequency of dosing must be used with therapeutic drug monitoring when possible. Use of alternative drugs without these metabolic characteristics is advised when possible with concomitant Korlym.

If drugs that undergo low first pass metabolism by CYP3A or drugs in which CYP3A is not the major metabolic route are co-administered with Korlym, use the lowest dose of concomitant medication necessary, with appropriate monitoring and follow-up.

CYP3A Inhibitors

Medications that inhibit CYP3A could increase plasma mifepristone concentrations and dose reduction of Korlym may be required.

Ketoconazole and other strong inhibitors of CYP3A, such as itraconazole, nefazodone, ritonavir, nelfinavir, indinavir, atazanavir, amprenavir and fosamprenavir, boceprevir, clarithromycin, conivaptan, lopinavir, mibefradil, , posaconazole, , saquinavir, telaprevir, telithromycin, or voriconazole may increase exposure to mifepristone significantly. The clinical impact of this interaction has not been studied. Therefore, extreme caution should be used when these drugs are prescribed in combination with Korlym. The benefit of concomitant use of these agents should be carefully weighed against the potential risks. The dose of Korlym should be limited to 300 mg and used only when necessary.

Moderate inhibitors of CYP3A, such as amprenavir, aprepitant, atazanavir, ciprofloxacin, darunavir/ritonavir, diltiazem, erythromycin, fluconazole, fosamprenavir, grapefruit juice, imatinib, or verapamil, should be used with caution when administered in combination with Korlym.

CYP3A Inducers

No medications that induce CYP3A have been studied when co-administered with Korlym. Avoid co-administration of Korlym and CYP3A inducers such as rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and St. John's wort.

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2C8/2C9

Because Korlym is an inhibitor of CYP2C8/2C9, concurrent use of Korlym with a drug whose metabolism is largely or solely mediated by CYP2C8/2C9 is likely to result in increased plasma concentrations of the drug.

Korlym significantly increased exposure of fluvastatin, a typical CYP2C8/2C9 substrate, in healthy subjects. When given concomitantly with Korlym, drugs that are substrates of CYP2C8/2C9 (including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin, and repaglinide) should be used at the smallest recommended doses, and patients should be closely monitored for adverse effects.

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2B6

Mifepristone is an inhibitor of CYP2B6 and may cause significant increases in exposure of drugs that are metabolized by CYP2B6 such as bupropion and efavirenz. Since no study has been conducted to evaluate the effect of mifepristone on substrates of CYP2B6, the concomitant use of bupropion and efavirenz should be undertaken with caution.

Use of Hormonal Contraceptives

Mifepristone is a progesterone-receptor antagonist and will interfere with the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives. Therefore, non-hormonal contraceptive methods should be used.

Use in Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Pregnancy Category (FDA): X

Contraindicated in pregnancy. Korlym can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman because the use of Korlym results in pregnancy loss. The inhibition of both endogenous and exogenous progesterone by mifepristone at the progesterone receptor results in pregnancy loss. If Korlym is used during pregnancy or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this drug, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to a fetus.

Pregnancy Category (AUS):

There is no Australian Drug Evaluation Committee (ADEC) guidance on usage of Mifepristone in women who are pregnant.

Labor and Delivery

There is no FDA guidance on use of Mifepristone during labor and delivery.

Nursing Mothers

Mifepristone is present in human milk of women taking the drug. Because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants from Korlym, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness of Korlym in pediatric patients have not been established.

Geriatic Use

Clinical studies with Korlym did not include sufficient numbers of patients aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently than younger people.

Gender

There is no FDA guidance on the use of Mifepristone with respect to specific gender populations.

Race

There is no FDA guidance on the use of Mifepristone with respect to specific racial populations.

Renal Impairment

The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in subjects with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance [CrCL] < 30 mL/min, but not on dialysis) was evaluated following multiple doses of 1200 mg Korlym for 7 days. Mean exposure to mifepristone increased 31%, with similar or smaller increases in metabolite exposure as compared to subjects with normal renal function (CrCL ≥ 90 mL/min). There was large variability in the exposure of mifepristone and its metabolites in subjects with severe renal impairment as compared to subjects with normal renal function (geometric least square mean ratio [CI] for AUC of mifepristone: 1.21 [0.71-2.06]; metabolite 1: 1.43 [0.84-2.44]; metabolite 2: 1.18 [0.64-2.17] and metabolite 3: 1.19 [0.71-1.99]). No change in the initial dose of Korlym is needed for renal impairment; the maximum dose should not exceed 600 mg per day.

Hepatic Impairment

The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh Class B) was evaluated in a single- and multiple-dose study (600 mg for 7 days). The pharmacokinetics in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment was similar to those with normal hepatic function. There was large variability in the exposure of mifepristone and its metabolites in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment as compared to subjects with normal hepatic function (geometric least square mean ratio [CI] for AUC of mifepristone: 1.02 [0.59-1.76]; metabolite 1: 0.95 [0.52-1.71]; metabolite 2: 1.37 [0.71-2.62] and metabolite 3: 0.62 [0.33-1.16]). Due to limited information on safety in patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment, the maximum dose should not exceed 600 mg per day. The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in patients with severe hepatic disease has not been studied. Korlym is not recommended in patients with severe hepatic disease.

Females of Reproductive Potential and Males

Due to its anti-progestational activity, Korlym causes pregnancy loss. Exclude pregnancy before the initiation of treatment with Korlym or if treatment is interrupted for more than 14 days in females of reproductive potential. Recommend contraception for the duration of treatment and for one month after stopping treatment using a non-hormonal medically acceptable method of contraception. If the patient has had surgical sterilization, no additional contraception is needed.

Immunocompromised Patients

There is no FDA guidance one the use of Mifepristone in patients who are immunocompromised.

Administration and Monitoring

Administration

Oral

Monitoring

- Adrenal insufficiency: Patients should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency.

- Hypokalemia: Hypokalemia should be corrected prior to treatment and monitored for during treatment.

IV Compatibility

There is limited information regarding the compatibility of Mifepristone and IV administrations.

Overdosage

There is no experience with overdosage

Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

Mifepristone is a selective antagonist of the progesterone receptor at low doses and blocks the glucocorticoid receptor (GR-II) at higher doses. Mifepristone has high affinity for the GR-II receptor but little affinity for the GR-I (MR, mineralocorticoid) receptor. In addition, mifepristone appears to have little or no affinity for estrogen, muscarinic, histaminic, or monoamine receptors.

Structure

There is limited information regarding Mifepristone Structure in the drug label.

Pharmacodynamics

Because mifepristone acts at the receptor level to block the effects of cortisol, its antagonistic actions affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in such a way as to further increase circulating cortisol levels while, at the same time, blocking their effects.

Mifepristone and the three active metabolites have greater affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor (100%, 61%, 48%, and 45%, respectively) than either dexamethasone (23%) or cortisol (9%).

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Following oral administration, time to peak plasma concentrations of mifepristone occurred between 1 and 2 hours following single dose, and between 1 and 4 hours following multiple doses of 600 mg of Korlym in healthy volunteers. Mean plasma concentrations of three active metabolites of mifepristone peak between 2 and 8 hours after multiple doses of 600 mg/day, and the combined concentrations of the metabolites exceed that of the parent mifepristone. Exposure to mifepristone is substantially less than dose proportional. Time to steady state is within 2 weeks, and the mean (SD) half-life of the parent mifepristone was 85 (61) hours following multiple doses of 600 mg/day of Korlym. Studies evaluating the effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of Korlym demonstrate a significant increase in plasma levels of mifepristone when dosed with food. To achieve consistent plasma drug concentrations, patients should be instructed to always take their medication with meals.

Distribution

Mifepristone is highly bound to alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG) and approaches saturation at doses of 100 mg (2.5 μM) or more. Mifepristone and its metabolites also bind to albumin and are distributed to other tissues, including the central nervous system (CNS). As determined in vitro by equilibrium dialysis, binding of mifepristone and its three active metabolites to human plasma proteins was concentration-dependent. Binding was approximately 99.2% for mifepristone, and ranged from 96.1 to 98.9% for the three active metabolites at clinically relevant concentrations.

Metabolism

Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) has been shown to be involved in mifepristone metabolism in human liver microsomes. Two of the known active metabolites are the product of demethylation (one monodemethylated and one di-demethylated), while a third active metabolite results from hydroxylation (monohydroxylated).

Elimination and Excretion

Excretion is primarily (approximately 90%) via the fecal route.

Nonclinical Toxicology

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Mifepristone was evaluated for carcinogenicity potential in rats and mice. Rats were dosed for up to two years at doses of 5, 25, and 125 mg/kg of mifepristone. The high dose was the maximum tolerated dose, but exposure at all doses was below exposure at the maximum clinical dose based on AUC comparison. Female rats had a statistically significant increase in follicular cell adenomas/carcinomas and liver adenomas. It is plausible that these tumors are due to drug-induced enzyme metabolism, a mechanism not considered clinically relevant, but studies confirming this mechanism were not conducted with mifepristone. Mice were also tested for up to 2 years at mifepristone doses up to the maximum tolerated dose of 125 mg/kg, which provided exposure below the maximum clinical dose based on AUC. No drug-related tumors were seen in mice. Mifepristone was not genotoxic in a battery of bacterial, yeast, and mammalian in vitro assays, and an in vivo micronucleus study in mice.

The pharmacological activity of mifepristone disrupts the estrus cycle of adult rats at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg (less than human exposure at the maximum clinical dose, based on body surface area). However, following withdrawal of treatment and subsequent resumption of the estrus cycle, there was no effect on reproductive function when mated. A single subcutaneous dose of mifepristone (up to 100 mg/kg) to rats on the first day after birth did not adversely affect future reproductive function in males or females, although the onset of puberty was slightly premature in dosed females. Repeated doses of mifepristone (1 mg every other day) to neonatal rats resulted in potentially adverse fertility effects, including oviduct and ovary malformations in females, delayed male puberty, deficient male sexual behavior, reduced testicular size, and lowered ejaculation frequency. Mifepristone was not genotoxic in a battery of bacterial, yeast, and mammalian in vitro assays, and an in vivo micronucleus study in mice.

The pharmacological activity of mifepristone disrupts the estrus cycle of adult rats at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg (less than human exposure at the maximum clinical dose, based on body surface area). However, following withdrawal of treatment and subsequent resumption of the estrus cycle, there was no effect on reproductive function when mated.

A single subcutaneous dose of mifepristone (up to 100 mg/kg) to rats on the first day after birth did not adversely affect future reproductive function in males or females, although the onset of puberty was slightly premature in dosed females. Repeated doses of mifepristone (1 mg every other day) to neonatal rats resulted in potentially adverse fertility effects, including oviduct and ovary malformations in females, delayed male puberty, deficient male sexual behavior, reduced testicular size, and lowered ejaculation frequency.

Clinical Studies

Cushing's Syndrome

Results in the Diabetes Cohort

Patients in the diabetes cohort underwent standard oral glucose tolerance tests at baseline and periodically during the clinical study. Anti-diabetic medications were allowed but had to be kept stable during the trial and patients had to be on stable anti-diabetic regimens prior to enrollment. The primary efficacy analysis for the diabetes cohort was an analysis of responders. A responder was defined as a patient who had a ≥ 25% reduction from baseline in glucose AUC. The primary efficacy analysis was conducted in the modified intent-to-treat population (n=25) defined as all patients who received a minimum of 30 days on Korlym. Fifteen of 25 patients (60%) were treatment responders (95% CI: 39%,78%).

Mean HbA1c was 7.4% in the 24 patients with HbA1c values at baseline and Week 24. For these 24 patients mean reduction in HbA1c was 1.1% (95% CI -1.6, -0.7) from baseline to the end of the trial. Fourteen of 24 patients had above normal HbA1c levels at baseline, ranging between 6.7% and 10.4%; all of these patients had reductions in HbA1c by the end of the study (range -0.4 to -4.4%) and eight of 14 patients (57%) normalized HbA1c levels at trial end. Antidiabetic medications were reduced in 7 of the 15 DM subjects taking antidiabetic medication and remained constant in the others.

Results in the Hypertension Cohort

There were no changes in mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures at the end of the trial relative to baseline in the modified intent-to-treat population (n=21).

Signs and symptoms of Cushing's syndrome in both cohorts

Individual patients showed varying degrees of improvement in Cushing's syndrome manifestations such as cushingoid appearance, acne, hirsutism, striae, psychiatric symptoms, and excess total body weight. Because of the variability in clinical presentation and variability of response in this open label trial, it is uncertain whether these changes could be ascribed to the effects of Korlym.

How Supplied

Korlym is supplied as a light yellow to yellow, film-coated, oval-shaped tablet debossed with “Corcept” on one side and “300” on the other. Each tablet contains 300 mg of mifepristone. Korlym tablets are available in bottles of 28 tablets (NDC 76346-073-01) and bottles of 280 tablets (NDC 76346-073-02).

Storage

Store at controlled room temperature, 25 °C (77 °F); excursions permitted to 15 to 30 ° C (59 – 86 °F).

Images

Drug Images

{{#ask: Page Name::Mifepristone |?Pill Name |?Drug Name |?Pill Ingred |?Pill Imprint |?Pill Dosage |?Pill Color |?Pill Shape |?Pill Size (mm) |?Pill Scoring |?NDC |?Drug Author |format=template |template=DrugPageImages |mainlabel=- |sort=Pill Name }}

Package and Label Display Panel

{{#ask: Label Page::Mifepristone |?Label Name |format=template |template=DrugLabelImages |mainlabel=- |sort=Label Page }}

Patient Counseling Information

As a part of patient counseling, doctors must review the Korlym Medication Guide with every patient.

Importance of Preventing Pregnancy

Advise patients that Korlym will cause termination of pregnancy. Korlym is contraindicated in pregnant patients. Counsel females of reproductive potential regarding pregnancy prevention and planning with a non-hormonal contraceptive prior to use of Korlym and up to one month after the end of treatment. Instruct patients to contact their physician immediately if they suspect or confirm they are pregnant.

Precautions with Alcohol

Alcohol-Mifepristone interaction has not been established. Talk to your doctor about the effects of taking alcohol with this medication.

Brand Names

Look-Alike Drug Names

There is limited information regarding Mifepristone Look-Alike Drug Names in the drug label.

Drug Shortage Status

Price

References

The contents of this FDA label are provided by the National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Urquhart DR, Templeton AA (1990). "Mifepristone (RU 486) for cervical priming prior to surgically induced abortion in the late first trimester". Contraception. 42 (2): 191–9. PMID 2085969.

- ↑ Xiao BL, Von Hertzen H, Zhao H, Piaggio G (2002). "A randomized double-blind comparison of two single doses of mifepristone for emergency contraception". Hum Reprod. 17 (12): 3084–9. PMID 12456607.

- ↑ "Comparison of three single doses of mifepristone as emergency contraception: a randomised trial. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation". Lancet. 353 (9154): 697–702. 1999. PMID 10073511.

- ↑ Glasier A (1997). "Emergency postcoital contraception". N Engl J Med. 337 (15): 1058–64. doi:10.1056/NEJM199710093371507. PMID 9321535.

- ↑ Cheng L, Zhu H, Wang A, Ren F, Chen J, Glasier A (2000). "Once a month administration of mifepristone improves bleeding patterns in women using subdermal contraceptive implants releasing levonorgestrel". Hum Reprod. 15 (9): 1969–72. PMID 10966997.

- ↑ Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Harwood BJ (2006). "Mifepristone and misoprostol for the treatment of early pregnancy failure: a pilot clinical trial". Contraception. 74 (6): 458–62. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.007. PMID 17157102.

- ↑ Cabrol D, Dubois C, Cronje H, Gonnet JM, Guillot M, Maria B; et al. (1990). "Induction of labor with mifepristone (RU 486) in intrauterine fetal death". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 163 (2): 540–2. PMID 2201190.

- ↑ Padayachi T, Moodley J, Norman RJ, Heyns A (1989). "Termination of pregnancy with mifepristone after intra-uterine death. Clinical and hormonal effects". S Afr Med J. 75 (11): 540–2. PMID 2658142.

- ↑ Rocereto TF, Saul HM, Aikins JA, Paulson J (2000). "Phase II study of mifepristone (RU486) in refractory ovarian cancer". Gynecol Oncol. 77 (3): 429–32. doi:10.1006/gyno.2000.5789. PMID 10831354.

- ↑ Eisinger SH, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, le Roux HD, Guzick DS (2003). "Low-dose mifepristone for uterine leiomyomata". Obstet Gynecol. 101 (2): 243–50. PMID 12576246.

{{#subobject:

|Label Page=Mifepristone |Label Name=28.png

}}

{{#subobject:

|Label Page=Mifepristone |Label Name=280.png

}}

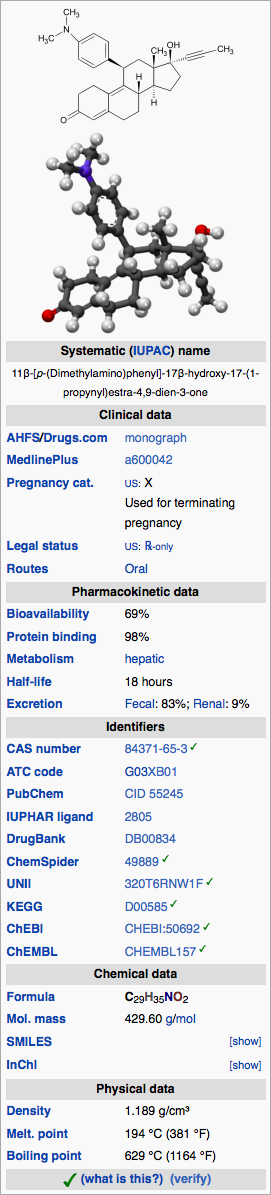

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 69% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 18 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal: 83%; Renal: 9% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H35NO2 |

| Molar mass | 429.60 g/mol |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Mifepristone |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Mifepristone Most cited articles on Mifepristone |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Mifepristone |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Mifepristone at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Mifepristone at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Mifepristone

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Mifepristone Discussion groups on Mifepristone Patient Handouts on Mifepristone Directions to Hospitals Treating Mifepristone Risk calculators and risk factors for Mifepristone

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Mifepristone |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [3]

Mifepristone is a synthetic steroid compound used as a pharmaceutical. It is used as an abortifacient in the first two months of pregnancy, and in smaller doses as an emergency contraceptive. It can also be used as a treatment for obstetric bleeding.[4] During early trials, it was known as RU-486, its designation at the Roussel Uclaf company, which designed the drug. The drug was initially made available in France, and other countries then followed—often amid controversy. In France and countries other than the United States it is marketed and distributed by Exelgyn Laboratories under the tradename Mifegyne. In the United States it is sold by Danco Laboratories under the tradename Mifeprex. (The drug is still commonly referred to as "RU-486".)

Pharmacology

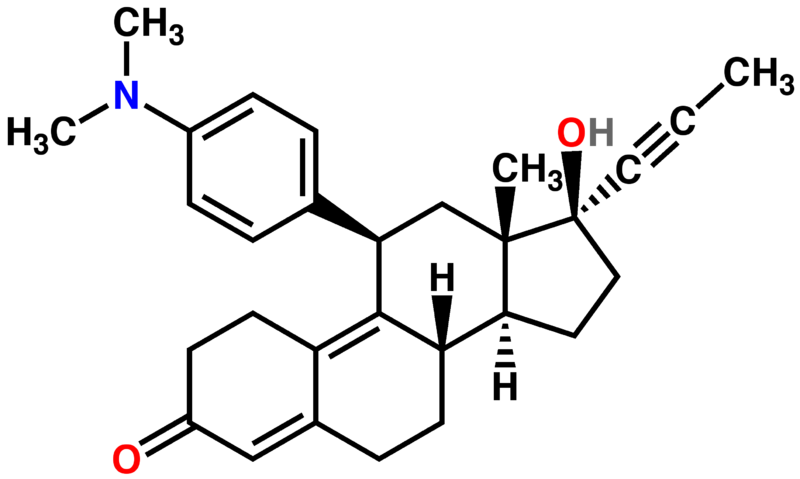

Mifepristone is a 19-nor steroid with a bulky p-(dimethylamino)phenyl substituent above the plane of the molecule at the 11β-position responsible for inducing or stabilizing an inactive receptor conformation and a hydrophobic 1-propynyl substituent above the plane of the molecule at the 17α-position that increases its progesterone receptor binding affinity. In the presence of progesterone, mifepristone acts as a competitive receptor antagonist at the progesterone receptor (in the absence of progesterone, mifepristone acts as a partial agonist).[1][2][3]

In addition to being an antiprogestogen, mifepristone is also an antiglucocorticoid and a weak antiandrogen. Mifepristone's relative binding affinity at the progesterone receptor is more than twice that of progesterone, its relative binding affinity at the glucocorticoid receptor is more than three times that of dexamethasone and more than ten times that of cortisol, its relative binding affinity at the androgen receptor is less than one third that of testosterone. It does not bind to the estrogen receptor or the mineralocorticoid receptor.[4]

Mifepristone as a regular contraceptive at 2 mg daily prevents ovulation (1 mg daily does not). A single preovulatory 10 mg dose of mifepristone delays ovulation by 3 to 4 days and is as effective an emergency contraceptive as a single 1.5 mg dose of the progestin levonorgestrel.[5]

In women, mifepristone at doses greater or equal to 1 mg/kg antagonizes the endometrial and myometrial effects of progesterone. In humans, an antiglucocorticoid effect of mifepristone is manifested at doses greater or equal to 4.5 mg/kg by a compensatory increase in ACTH and cortisol. In animals, a weak antiandrogenic effect is seen with prolonged administration of very high doses of 10 to 100 mg/kg.[6][7]

In medical abortion regimens, mifepristone blockade of progesterone receptors directly causes endometrial decidual degeneration, cervical softening and dilatation, release of endogenous prostaglandins and an increase in the sensitivity of the myometrium to the contractile effects of prostaglandins. Mifepristone induced decidual breakdown indirectly leads to trophoblast detachment, resulting in decreased syncytiotrophoblast production of hCG, which in turn causes decreased production of progesterone by the corpus luteum (pregnancy is dependent on progesterone production by the corpus luteum through the first 9 weeks of gestation--until placental progesterone production has increased enough to take the place of corpus luteum progesterone production). When followed sequentially by a prostaglandin, mifepristone 200 mg is (100 mg may be, but 50 mg is not) as effective as 600 mg in producing a medical abortion.[1][3]

Approved uses

Template:Infobox abortion method

Mifegyne is sold outside the U.S. by Exelgyn Laboratories, made in France, and is approved for:

- Medical termination of intrauterine pregnancies of up to 49 days gestation (up to 63 days gestation in Britain and Sweden)

- Softening and dilatation of the cervix prior to mechanical cervical dilatation for pregnancy termination

- Use in combination with gemeprost for termination of pregnancies between 13 and 24 weeks gestation

- Labor induction in fetal death in utero.[6]

Mifeprex is sold in the U.S. by Danco Laboratories, made in China,[8] and is FDA-approved in the U.S. to terminate intrauterine pregnancies of up to 49 days gestation. Under the FDA-approved regimen, a 600 mg dose is administered by a clinician following a counseling session. Two days later, a clinician administers 400 µg of another medicine, misoprostol, to induce contractions. In European studies, this method terminated 96 to 99% of pregnancies of up to 49 days gestation, but in one large multicenter trial in the U.S. conducted from September 1994 to September 1995, the efficacy was lower (92%), which the authors of the study suggested may have been due to lack of experience with this method in the U.S. and/or the design of their study.[9] In Europe and China, an observation period of several hours is required after administration of misoprostol. If expulsion of fetal tissue does not occur during the observation period, surgical abortion is offered. There is no required observation period in the U.S., but it is strongly recommended.[10]

According to the current Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists abortion clinical guideline:[11]

- Medical abortion using mifepristone plus prostaglandin is the most effective method of abortion at gestations of less than 7 weeks.

- Conventional vacuum aspiration should be avoided at gestations below 7 weeks.

- Early vacuum aspiration using a rigorous protocol (which includes magnification of aspirated material and indications for serum βhCG follow-up) may be used at gestations below 7 weeks, although data suggest that the failure rate is higher than for medical abortion.

- Medical abortion using mifepristone plus prostaglandin continues to be an appropriate method for women in the 7–9 week gestation band.

Mifepristone can also be used in smaller doses as an emergency contraceptive; if taken after sex but before ovulation, it can prevent ovulation and so prevent pregnancy. In this role, a 10 mg dose is not as effective as the 600 mg dose, but has fewer side-effects.[12] Mifeprex and Mifegyne are only available in 200 mg tablets.[13] A review of studies in humans found that the contraceptive effects of the 10 mg dose were probably due mainly to its effects on ovulation, and not inhibition of implantation, but "the knowledge of the mechanism of action remains incomplete." Treatment with 200 mg of mifepristone changes steroid receptor expression in the fallopian tube, inhibits endometrial development, and effectively prevents implantation.[14]

Other uses

Other medical applications of mifepristone that have been studied in Phase II clinical trials include regular long-term use as an oral contraceptive, and treatment of: uterine fibroids, endometriosis, major depression with psychotic features, glaucoma, meningiomas, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, and some types of Cushing's syndrome. [2][5][15] Mifepristone has not been approved by the FDA for any of these uses.

Side effects and contraindications

In clinical trials, nearly all women using mifepristone experienced abdominal pain, uterine cramping, and vaginal bleeding or spotting for an average of 9–16 days. Up to 8% of women experienced some type of bleeding for 30 days or more. Other less common side effects included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, fatigue, and fever.[16] Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is a very rare but serious complication.[17] Excessive bleeding and incomplete termination of a pregnancy require further intervention by a doctor (such as vacuum aspiration). Between 4.5 and 7.9% of women required surgical intervention in clinical trials.[16] Mifepristone is contraindicated in the presence of an intrauterine device (IUD), as well as with ectopic pregnancy, adrenal failure, hemorrhagic disorders, inherited porphyria, and anticoagulant or long-term corticosteroid therapy.[16]

The FDA prescribing information states that there are no data on the safety and efficacy of mifepristone in women with chronic medical conditions, and that "women who are more than 35 years of age and who also smoke 10 or more cigarettes per day should be treated with caution because such patients were generally excluded from clinical trials of mifepristone."[16]

Carcinogenicity and teratogenicity

No long-term studies to evaluate the carcinogenic potential of mifepristone have been performed. Results from studies conducted in vitro and in animals have revealed no genotoxic potential for mifepristone. A preliminary study in mice indicates that a single dose of mifepristone inhibited apoptosis of liver cells in the treated rats, which the authors hypothesized might increase susceptibility to hepatic cancer.[18]

Neonatal exposure to a single large dose of mifepristone in rats was not associated with any reproductive problems, although chronic low-dose exposure of newborn rats to mifepristone was associated with structural and functional reproductive abnormalities.[16]

Teratology studies in mice, rats and rabbits revealed teratogenicty for rabbits, but not rats or mice.[16] The rate of birth defects in human infants exposed in utero to mifepristone and misoprostol is very low,[19] and may be due to misoprostol alone.[20]

History

The compound was discovered by researchers at Roussel Uclaf of France in 1980 (the "RU" in RU-486) while they were studying glucocorticoid receptor antagonists. Clinical testing began in 1982. The drug was first licensed in France in 1988, for use in combination with a prostaglandin, under the name Mifegyne. After license approval but before market release, Roussel Uclaf announced it would abandon distribution of the drug, bowing to pressure from pro-life groups and the threat of a boycott. However, two days later, the French government, part owner of Roussel Uclaf, intervened, leading to the resumption of production and distribution of RU-486. The French Health Minister, explaining the government's intervention, stated, "I could not permit the abortion debate to deprive women of a product that represents medical progress. From the moment Government approval for the drug was granted, RU-486 became the moral property of women."[21]

In early 1990, an international group of scientists and doctors based at the Necker Hospital in Paris reviewed the data of 30,000 women who had used RU 486 and issued a stern warning against it. They urged the Ministry of Health ‘to enforce what was inevitable: the immediate suppression of the distribution and use of RU 486.' The French government did not ban it, but did issue stricter guidelines for its use. (Klein et al)

Roussel Uclaf did not seek U.S. approval, so US availability was not an initial possibility.[22] The first Bush administration banned importation of Mifepristone for personal use in 1989, a decision supported by Roussel Uclaf. This ban was not reversed until 1993, by President Clinton. In 1994, Roussel Uclaf gave the U.S. drug rights to the Population Council in exchange for immunity from any product liability claims.[23][24] The Population Council sponsored US clinical trials[25] The drug went on approvable status from 1996. Production was intended to begin through the Danco Group in 1996 but they withdrew briefly in 1997 due to a corrupt business partner, delaying availability again.[26][27] Mifepristone was approved by the FDA in September 2000.[28] It is legal and available in all 50 states, Washington DC, Guam and Puerto Rico.[29] Medical abortions as a percentage of total abortions in the United States have increased every year since the approval of mifepristone: 1.0% in 2000, 2.9% in 2001, 5.2% in 2002, 7.9% in 2003; although data is limited by seven states not reporting statistics to the CDC (including California where an estimated >23% of total U.S. abortions were performed in 1997).[30]

Subsection H

Some drugs are approved by the FDA under sub-section H, which has two sub-parts. The first sets forth ways to rush experimental drugs, such as aggressive HIV and cancer treatments, to market when speedy approval is deemed vital to the health of potential patients. The second part of sub-section H applies to drugs that not only must meet restrictions for use due to safety requirements, but also are required to meet postmarketing surveillance to establish that the safety results shown in clinical trials are seconded by use in a much wider population. Mifepristone was approved under the second part of sub-section H. The result is that women cannot pick the drug up at a pharmacy but must now receive it directly from a doctor. Due to the possibility of adverse reactions such as excessive bleeding which may require a blood transfusion and incomplete abortion which may require surgical intervention, the drug is only considered safe if a physician who is capable of administering a blood transfusion or a surgical abortion is available to the patient in the event of such emergencies.[31] The approval of mifepristone under Subsection H included a black box warning.

Controversy

Many pro-life groups in the US actively campaigned against the approval of mifepristone,[32][33][34] and continue to actively campaign for its withdrawal.[35] They cite either ethical issues with abortion or safety concerns regarding the drug and the adverse reactions associated with it, including death.[36] The proposed "RU-486 Suspension and Review Act," also known as Holly's Law, was initiated by a citizen's petition to the FDA from namesake Holly Patterson's father,[37] and the May 17, 2006 House Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources hearing entitled "RU-486 - Demonstrating a Low Standard for Women’s Health?”[38]—called by its pro-life chairman Rep. Mark Souder—are the principal results of this effort. Religious and pro-life groups outside the US have also protested mifepristone, especially in Germany[39] and Australia.[40][41]

A small but vocal group of female scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Institute on Women and Technology issued a report under the name of "Feminist International Network of Resistance to Reproductive and Genetic Engineering" in the early 90s to express their opposition to mifepristone, because "We felt what was being lost in the political debate was how the drug affects women. In contrast with the groups who are anti-feminist and anti-abortion, the Institute on Women and Technology advocates women's rights to abortion and self determination," said Dr. Janice Raymond of FINRRAGE. Additional feminist critics exist, such as Pauline Connor (LI.B.) of Feminists Against Eugenics in England who stated, "What has been presented as a simple, pill-popping exercise is, in fact, an intensely medicalized and painful procedure which can involve up to four clinic visits and last 12 days."[42]

That mifepristone can be used as an abortifacient has also been a barrier to its adoption as a treatment for obsetric bleeding of particular value in the developing world (as it is low cost and heat stable).[5]

Fatalities

Since FDA approval in 2000, eight women in the US, two women in the UK,[43] one woman in Sweden, and one in Canada have died following use of mifepristone. As a result of these deaths, two US Senators introduced legislation calling for an immediate ban on the sale of Mifeprex, pending FDA review.[44] According to a United States House of Representatives Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources document, the number of patient fatalities in the US related to mifepristone abortions is estimated at 1.39 in 100,000, almost fourteen times the rate for suction-aspiration abortions of comparable terms (8 weeks gestation).[45] According to The New York Times, the risk is "a bit more than 1 in 100,000," and "some deaths may have gone unreported, meaning the real risk may be even higher."[46]

Recently, the FDA has released information about the deaths of five American women who had mifepristone abortions. The deaths all occurred after intravaginal administration of the second medication, misoprostol, which is only FDA approved for oral use. Some medical abortion providers in the US have since stopped prescribing intravaginal placement of misoprostol.[47] Off-label intra-vaginal use of misoprostol has been shown to be effective in published studies, but not in clinical trials. The FDA has not reviewed the safety of off-label intravaginal misoprostol, and cannot do so unless the manufacturer submits data from clinical trials and requests a review. One of the reported deaths occurred due to the rupturing of an undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy. Termination of ectopic pregnancies using mifepristone is contraindicated but can sometimes be difficult to detect, even by ultrasound.[48] There have been 27 reported cases of accidental use of mifepristone during ectopic pregnancy.[45] The FDA has concluded that there is no established causal link between the deaths and mifepristone,[49] but also states that they "do not know whether using Mifeprex or misoprostol caused these deaths."[50] An American microbiologist who first linked tampons to fatal toxic shock syndrome said vaginal administration of misoprostol should be prohibited because it can increase infection risk. "That may, in and of itself, eliminate the problem," said Philip M. Tierno, director of clinical microbiology and immunology at New York University Medical Center.[51]

On May 11, 2006, experts from the FDA, the CDC, and the NIH gathered in Atlanta, Georgia for a meeting regarding cloistridal disease, partly in response to the five confirmed deaths resulting from bacterial infection.[52] While the five deaths were verified as being linked to Clostridium sordellii infection, the cause of the infection is still unknown. While clostridium is a normal flora inhabitant of the vagina in 5-10% of women (a percentage which increases with pregnancy) clostridium infections are extremely rare, and have occurred not just with Mifeprex, but also after normal postpartum delivery, although in a fewer relative number of cases.[53]

Dr. Ralph Miech, associate professor emeritus of molecular pharmacology, physiology and biotechnology at Brown University, has asserted that mifepristone is immunosuppressive, and that impairment of the body's natural immunity allows the endometrial spread of C. sordellii infection.[54] Dr. Lisa Rarick, obstetrician/gynecologist and former FDA official, testifying at the House subcommittee hearing, contradicted this theory by observing that "immune suppression-associated infection would not appear as reports of infections of only one organism."[55] But Dr. Renate Klein, biologist, associate professor of women's studies at Deakin University, member of FINRRAGE, and author of several books on reproductive technology, and Dr. Lynette Dumble, a medical scientist who spent 27 years in the surgery department of Royal Melbourne Hospital, affirm the immunosuppressive capability of the medical abortion regimen: "We are unaware of any studies which assure healthy women that RU 486 and PG, taken together, does not weaken immune defence against malignancy and infection. Synthetic PG (prostaglandin) analogues, in microgram amounts, induce sufficient immune suppression in animals to delay the rejection of experimental, heart and kidney transplants. Until proven otherwise, women's exposure to synthetic PG during abortion procedures can be regarded as an immune insult."[56] They also note, "Proponents of PGs in pregnancy-related procedures claim that a single exposure to a 'small dose of prostaglandin' has no effect on the immune system, but Di Francesco et al, (1990)[57] have reported that isolated immune insults are more harmful than those of a chronic nature (as practised in transplantation)."[56] Dr. Miech has also stated, as a panel expert at the "Emerging Cloistridal Disease Workshop," that "the hypothesis that mifepristone could facilitate infection and lead to lethal septic shock is supported by animal experimentation," and Dr. Esther Sternberg of the NIH, fellow panel expert, has reported both that even endotoxin-nonresponsive mice can be made endotoxin sensitive by mifepristone, and that mifepristone enhances the severity and lethality of bacterial and viral infections, by suppressing the immune response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.[58] In addition to the studies cited by Sternberg, a 1992 study of female rats treated with mifepristone found that some developed lethal bacterial infections.[59]

Dr. Marc Fischer, CDC medical epidemiologist, states that because vaginal flora constantly vary according to many factors, "the apparent association between C. sordellii toxic shock syndrome and gynecologic infections may be attributed to a rare confluence of events." They also note that pregnancy, childbirth, or abortion "may predispose a small number of women to acquire C. sordellii in the vaginal tract, with dilation of the cervix allowing for ascending infection of necrotic decidual tissue."[60]

Misoprostol not only dilates the cervix, but also softens it. It can also cause uterine ruptures.[61][62] It is not approved by the FDA for uses other than the prevention and treatment of ulcers, and the FDA has sent out a warning letter regarding the dangers of off-label use of misoprostol to induce labor.[63] Drug combinations, in which one drug is approved and the other is not (such as mifespristone + misoprostol), are sometimes allowed by the FDA.[64]

On July 20, 2005, the FDA updated the black box warning for Mifeprex, to inform patients of the sepsis cases, and to be alert to signs and symptoms, although the symptoms match those caused by mifepristone.[65]

Politics and use outside the United States

Europe

Mifepristone was approved for use in France in 1988 (initial marketing in 1989), the United Kingdom in 1991, Sweden in 1992, then Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland in 1999.[66] In 2000, it was approved in Norway. Serbia and Montenegro approved it in 2001,[67] Latvia in 2002, Estonia in 2003, Albania and Hungary in 2005.[68] In Sweden and the UK, mifepristone is licensed for use with vaginal gemeprost instead of oral misoprostol. As of seven years ago, more than 620,000 women in Europe had had medical abortions using a mifepristone regimen.[69] In France, the percentage of medical abortions continues to increase, from 38% of all abortions in 2003 to 42% of all abortions in 2004.[70] In England and Wales, 42% of early abortions (less than 9 weeks gestation) in 2006 were medical; the percentage of all abortions that are medical has increased every year for the past 11 years (from 5% in 1995 to 30% in 2006).[71] In Scotland, 77.8% of early abortions (less than 10 weeks gestation) in 2006 were medical; the percentage of all abortions that are medical has increased every year for the past 14 years (from 16.4% in 1992 to 59.1% in 2006).[72] In Sweden, 60.6% of early abortions (before the end of the 12th week of gestation) in 2006 were medical; 56.3% of all abortions in 2006 were medical.[73] In Denmark, mifepristone was used in between 3,000 and 4,000 of just over 15,000 abortions in 2005.[74] Mifepristone is not approved in Ireland, where abortion is illegal, or Poland, where abortion is highly restricted.[75] Clinical trials in Italy have been constrained by protocols requiring women be hospitalized for three days.[76] It was approved in Hungary in 2005, but as of 2005 had not been released on the market yet, and was the target of protests.[77]

Australia and New Zealand

Mifepristone was banned in Australia in 1996. In late 2005, a Private Member's bill was introduced to the Australian Senate to lift the ban and transfer the power of approval to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). The move caused much debate in the Australian media and amongst politicians. The Bill passed the Senate on 10 February 2006, and whilst mifepristone is now legal for use in Australia, as of yet, no drug company has applied to import and distribute it. Currently there are only a couple known instances where a doctor has applied to the TGA for dispensing mifepristone in specific cases.

In New Zealand, pro-choice doctors established an import company, Istar, and submitted a request for approval to MedSafe, the New Zealand pharmaceutical regulatory agency. After a court case brought by Right to Life New Zealand failed, use of mifepristone was permitted.[78]

Israel

Mifepristone was approved in Israel in 1999.[79]

Asia

Clinical trials of mifepristone in China began in 1985. In October 1988, China became the first country in the world to approve mifepristone. Chinese organizations tried to purchase mifepristone from Roussel Uclaf, but they refused to sell it to them, so in 1992 China began its own domestic production of mifepristone. In 2000, the cost of medical abortion with mifepristone was higher than surgical abortion and the percentage of medical abortions varied greatly, ranging from 30% to 70% in cities to being almost nonexistent in rural areas.[80][81] A report from the United States Embassy in Beijing in 2000 said mifepristone had been widely used in Chinese cites for about two years, and that according to press reports a black market had developed with many women starting to it illegally (without a prescription) from private clinics and drugstores for about $15, causing Chinese authorities to worry about medical complications from use without physician supervision.[82]

In 2001, mifepristone was approved in Taiwan.[83] Vietnam included mifepristone in the National Reproductive Health program in 2002.[84]

Africa

Mifepristone is approved in only one subsaharan African country--South Africa, where it was approved in 2001.[85] It is also approved in one north African country--Tunisia, also in 2001.[86]

India

Mifepristone was approved for use in India in 2002, where medical abortion is referred to as "Medical Termination of Pregnancy" (MTP). It is only available under medical supervision, not by prescription, due to adverse reactions such as excessive bleeding, and there are criminal penalties for buying or selling it on the black market or over-the-counter at pharmacies.[87]

Canada

Mifepristone is not available in Canada. Clinical trials were suspended in 2001 after the death of a woman from septic shock caused by clostridium sordelli.[88]

The former Soviet Union

Mifepristone was registered for use in Russia and Ukraine in 2000, and in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, and Uzbekistan in 2002, Moldova in 2004, and Armenia in 2007.[89][68]

South America, Central America, and Mexico

Mifepristone is not approved in any South American or Central American countries, or in Mexico.

Cuba

Mifepristone is legal in Cuba.

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Loose, Davis S.; Stancel, George M. (2006). "Estrogens and Progestins". In in Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith L. (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. pp. 1541-1571. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Schimmer, Bernard P.; Parker, Keith L. (2006). "Adrenocorticotropic Hormone; Adrenocortical Steroids and Their Synthetic Analogs; Inhibitors of the Synthesis and Actions of Adrenocortical Hormones". In in Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith L. (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. pp. 1587-1612. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fiala C, Gemzel-Danielsson K (2006). "Review of medical abortion using mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analogue". Contraception. 74 (1): 66–86. PMID 16781264.

- ↑ Heikinheimo O, Kekkonen R, Lahteenmaki P (2003). "The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in humans reveal insights into differential mechanisms of antiprogestin action". Contraception. 68 (6): 421–6. PMID 14698071.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chabbert-Buffet N, Meduri G, Bouchard P, Spitz IM (2005). "Selective progesterone receptor modulators and progesterone antagonists: mechanisms of action and clinical applications". Hum Reprod Update. 11 (3): 293–307. PMID 15790602.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Exelgyn Laboratories (2006). "Mifegyne UK Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". Retrieved 2007-03-09. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Danco Laboratories (2005). "Mifeprex US prescribing information" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-03-09. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Chinese to Make RU-486 for U.S." Washingtonpost.com. 2000. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Spitz IM, Bardin CW, Benton L, Robbins A (1998). "Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States". N Engl J Med. 338 (18): 1241–7. PMID 9562577.

- ↑ Suzanne Daley (October 5, 2000). "Europe Finds Abortion Pill is No Magic Cure-All". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ RCOG (2004). The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion (PDF). London: RCOG Press. ISBN 1-904752-06-3.

- ↑ Piaggio G; et al. (2003). "Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing different doses of mifepristone in emergency contraception". Contraception. 68 (6). PMID 14698075.

- ↑ Wertheimer, Randy E. (2000-11-15). "Emergency Postcoital Contraception" (HTML). American Family Physician. American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved 2006-07-23. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Gemzell-Danielsson, K. (2004-06-10). "Mechanisms of action of mifepristone and levonorgestrel when used for emergency contraception" (HTML). Human Reproduction Update. Oxford University Press. 10 (4): 341–348. Retrieved 2006-07-23. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Tang OS, Ho PC (2006). "Clinical applications of mifepristone". Gynecol Endocrinol. 22 (12): 655–9. PMID 17162706.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 "Mifeprex label" (PDF). FDA. 2005-07-19. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Lawton, BA; et al. (2006). "Atypical presentation of serious pelvic inflammatory disease following mifepristone-induced abortion". Contraception. 73 (4): 431-2. PMID 16531180.

- ↑ Youssef, Jihan and Badr, Mostafa (2003). "Hepatocarcinogenic potential of the glucocorticoid antagonist RU486 in B6C351 mice". Molecular Cancer. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ↑ Margaret M. Gary and Donna J. Harrison (December 2005). "Analysis of Severe Adverse Events Related to the Use of Mifepristone as an Abortifacient". The Annals of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ↑ Orioli, IM and Castilla, EE (2000). "Epidemiological assessment of misoprostol teratogenicity". BJOG. 107 (4): 519-23. PMID 10759272.

- ↑ Julie A. Hogan (2000). "The Life of the Abortion Pill in the United States". Legal Electronic Document Archive, Harvard Law School. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ↑ Klitsch M (Nov-December 1991). "Antiprogestins and the abortion controversy: a progress report". Fam Plann Perspect. 23 (6): 275-82. PMID 1786809. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Katharine Q. Seelye (1997-1-05-17). "Accord Opens Way for Abortion Pill in US in 2 Years". Retrieved 2006-08-26. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Nancy Gibbs (October 2, 2000). "The Pill Arrives". Cnn.com. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Tamar Lewin (January 30, 1995). "Clinical Trials Giving Glimpse of Abortion Pill". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Tamar Lewin (November 13, 1997). "Lawsuits' Settlement Brings New Hope for Abortion Pill". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ Sharon Lerner (August 2000). "RU Pissed Off Yet?". Village Voice. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ "FDA approval letter for Mifepristone". U.S. Gov. September 28, 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ "Medication Abortion in the United States: Mifepristone Fact Sheet". Gynuity Health Projects. 2005.

- ↑ Strauss LT, Gamble SB, Parker WY, Cook DA, Zane SB, Hamdan S (2006). "Abortion surveillance--United States, 2003" (PDF). MMWR Surveill Summ. 55 (11): 1–32. PMID 17119534.(no abortion statistics from CA, NH, WV; no medical abortion statistics from AL, GA, HI, LA)

- ↑ Woodcock, Janet (2006-05-12). "Testimony on RU-486". Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives. FDA. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Paige Comstock Cunningham, Leanne McCoy, Clarke D. Ferguson (February 28, 1995). "Citizen Petition to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration". Americans United for Life. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Margaret Talbot (July 11, 1999). "The Little White Bombshell". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ "Abortion Foes To Boycott Drugs (Altace) Made By RU-486 Manufacturer". The Virginia Pilot. July 8, 1994. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ↑ Stan Guthrie (June 11, 2001). "Counteroffensive Launched on RU-486". Christianity Today. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Gina Kolata (September 24, 2003). "Death at 18 Spurs Debate Over a Pill For Abortion". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Karen Tumulty (October 14, 2002). "Jesus and the FDA". Time. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ "RU-486 - Demonstrating a Low Standard for Women's Health?". House Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources. 2006-05-17. Retrieved 2006-08-25. Unknown parameter

|D=ignored (help) - ↑ John L. Allen (Feb. 12, 1999). "Abortion debates rock Germany: introduction of abortion pill exacerbates controversy". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 2006-09-14. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Catholic and Evangelical students join Muslims in RU-486 fight". Catholic News. February 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ↑ "Death Toll Rises to 11 Women". Australians Against RU-486. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Annette MacDonald (1992). "RU-486: A Dangerous Drug". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Michael Day and Susan Bisset (January 18, 2004). "Revealed: two British women die after taking controversial new abortion pill". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". FDA.gov. Unknown parameter

|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help)

"Two more women die after taking 'abortion pill'". CNN.com. Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help) - ↑ 45.0 45.1 "FDA Questions for the Record Following the Subcommittee Hearing, "RU-486: Demonstrating a Low Standard for Women's Health?"". Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources. Retrieved 2006-08-24. Unknown parameter

|D=ignored (help) - ↑ Gardiner Harris (April 1, 2006). "Some Doctors Voice Worry Over Abortion Pills' Safety". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-01-09.

- ↑ Gardiner Harris (March 18, 2006). "After 2 More Deaths, Planned Parenthood Alters Method for Abortion Pill". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ Timothy F. Kern (December 15, 2004). "Three deaths prompt new warnings for mifepristone". OB/GYN News. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ↑ "Mifepristone Questions and Answers". FDA.gov. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ "Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information". FDA.gov. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ Henderson, Diedtra (2006-12-01). "Article to kindle abortion pill fight". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ "Emerging Clostridial Disease Public Workshop". FDA. 2006-05-11. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ↑ Rorbye, C; et al. (2000). "Postpartum clostridium sordellii infection associated with fatal toxic shock syndrome". Acta obstetrica et gynecologica Scandinavica. 79 (12): 1134–5. PMID 1130102.

- ↑ Miech RP (2005). "Pathophysiology of mifepristone-induced septic shock due to Clostridium sordellii". Ann Pharmacother. 39 (9): 1483–8. PMID 16046483. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Written Testimony/Prepared Statement" (PDF). RU-486 - Demonstrating a Low Standard for Women’s Health?. House Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources. 2006-05-17. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Klein, Renate; Raymond, Janice G.; Dumble, Lynette J. (1991). RU 486 : misconceptions, myths, and morals. North Melbourne: Spinifex. ISBN 1-875559-01-9.

- ↑ Di Francesco P, Pica F, Tubaro E, Favalli C, Garaci E (1990). "Inhibitory effects of cocaine on the cellular immune response in normal mice (abstract)". In Samuelsson, Bengt (ed.) (1991). 7th International Conference on Prostaglandins and Related Compounds (Advances in Prostaglandin, Thromboxane, and Leukotriene Research). Florence, Italy. May 28-June 1, 1990. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. p. 336. ISBN 0-88167-742-6.

- ↑ Sternberg, Esther. "Role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, glucocorticoids, and glucocorticoid receptors in toxic sequelae of exposure to bacterial and viral products". 181 (2): 207–21. Unknown parameter

|years=ignored (help) - ↑ van der Schoot, P (1992). "Treatment with mifepristone (RU-486) and oestradiol facilitates the development of genital septic disease after copulation in female rats". 7 (5): 601–5. PMID 1639975.

- ↑ Fischer M, Bhatnagar J, Guarner J, Reagan S, Hacker JK, Van Meter SH, Poukens V, Whiteman DB, Iton A, Cheung M, Dassey DE, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR (2005). "Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion". N Engl J Med. 353 (22): 2352–60. PMID 16319384. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Kim, JO; et al. (November–December 2005). "Oral misoprostol and uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy: a case report". 20 (4): 575–77. PMID 15982851.

- ↑ Lialos, G; et al. (2006). "Uterine perforation as a rare complication of attempted pregnancy termination with misoprostol: a case report". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 51 (7): 599–600. PMID 16913556.

- ↑ "FDA Alert-Risks of Use in Labor and Delivery". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA. May, 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-21. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Some Hospitals Shun Drug Used with RU-486, Obstetricians Say Move is Harmful to Women". National Public Radio. October 12, 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ↑ "Patient Information Sheet: Mifepristone". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA. 2006-07. Retrieved 2006-08-19. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Christin-Maitre S, Bouchard P, Spitz IM (2000). "Medical termination of pregnancy". N Engl J Med. 342 (13): 946–56. PMID 10738054.

- ↑ Stojnic J; et al. (2006). "Medicamentous abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol in Serbia and Montenegro". 63 (6): 558-63. PMID 16796021.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Mifepristone approval" (PDF). Gynuity.org accessdate=2007-07-27. 2007.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Mifepristone for the Termination of Early Pregnancy". FDA press release/US Gov. 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Vilain, Annick (2006). "Voluntary terminations of pregnancies in 2004" (PDF). DREES, Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Department of Health (2007). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006". Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ ISD Scotland (2007). "Abortion Statistics 2006". Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden (2007). "Induced Abortions 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ "The abortion pill Mifegyne tested for adverse reactions". Danish Medicines Agency. July 27, 2005. Retrieved 2006-09-20. Unknown parameter

|D=ignored (help) - ↑ Peter S. Green (June 24, 2003). "A Rocky Landfall for a Dutch Abortion Boat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ Rey, Anne-Marie Rey (2006). "Abortion in Italy". SVSS-USPDA. Retrieved 2007-03-01. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Abortion pill sparks bitter protest". The Budapest Times. September 19, 2005. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ Sparrow MJ (2004). "A woman's choice". Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 44 (2): 88-92. PMID 15089829.

- ↑ Etienne-Emile Baulieu, Daniel S. Seidman, Selma Hajri (October 2001). "Mifepristone(RU-486) and voluntary termination of prgnancy: enigmatic variations or anecdotal religion-based attitudes?". Human Reproduction. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ Ulmann A (2000). "The development of mifepristone: a pharmaceutical drama in three acts". J Am Med Women's Assoc. 55 (3 Suppl): 117–20. PMID 10846319.

- ↑ Wu S (2000). "Medical abortion in China". J Am Med Women's Assoc. 55 (3 Suppl): 197–9, 204. PMID 10846339.

- ↑ "Family planning in China: RU-486, abortion, and population trends". U.S. Embassy Beijing. 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ↑ Tsai EM, Yang CH, Lee JN (2002). "Medical abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol: a clinical trial in Taiwanese women". J Formos Med Assoc. 101 (4): 277-82. PMID 12101864.

- ↑ Ganatra B, Bygdeman M, Nguyen DV, Vu ML, Phan BT (2004). "From research to reality: the challenges of introducing medical abortion into service delivery in Vietnam". Reprod Health Matters. 12 (24): 105-13. PMID 15938163.

- ↑ "Medical Abortion-Implications for Africa". Ipas. 2003. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ Hajri S (2004). "Medication abortion: the Tunisian experience". Afr J Reprod Health. 8 (1): 63-9. PMID 15487615.

- ↑ "Mifepristone can be sold only to approved MTP Centres: Rajasthan State HRC". Indian Express Health Care Management. 2000.

- ↑ Jennifer Laliberte (September 30, 2005). "Still no mifepristone for Canada: is it safe?". National Review of Medicine. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ "Medication Abortion". Ibis. 2002. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

See also

External links

- US Food and Drug Administration Mifeprex (mifepristone) Information

- Commonly asked questions about RU-486 from the education arm of the National Coalition of Abortion Providers

- A comprehensive listing of offices offering The Abortion Pill; all members of NCAP or NAF, the two main organizations advocating for abortion providers

- Danco prescribing information