Hospital-acquired pneumonia: Difference between revisions

Kashish Goel (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Kashish Goel (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

'''Hospital-acquired pneumonia''' (HAP) or ''' | '''Hospital-acquired pneumonia''' (HAP) or '''Health-Care associate pneumonia''' (HCAP) refers to any [[pneumonia]] contracted within 48-72 hours of being admitted in hospital. It is usually caused by a bacterial infection.<ref name="Mandell"> | ||

[http://www.ppidonline.com/ Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases] 6th Edition (2004) by Gerald L. Mandell MD, MACP, John E. Bennett MD, Raphael Dolin MD, ISBN 0-443-06643-4 · Hardback · 4016 Pages Churchill Livingstone</ref><ref name="Oxford">[http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Medicine/PrimaryCare/?ci=0192629220&view=usa The Oxford Textbook of Medicine] Edited by David A. Warrell, Timothy M. Cox and John D. Firth with Edward J. Benz, Fourth Edition (2003), [[Oxford University Press]], ISBN 0-19-262922-0</ref> | [http://www.ppidonline.com/ Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases] 6th Edition (2004) by Gerald L. Mandell MD, MACP, John E. Bennett MD, Raphael Dolin MD, ISBN 0-443-06643-4 · Hardback · 4016 Pages Churchill Livingstone</ref><ref name="Oxford">[http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Medicine/PrimaryCare/?ci=0192629220&view=usa The Oxford Textbook of Medicine] Edited by David A. Warrell, Timothy M. Cox and John D. Firth with Edward J. Benz, Fourth Edition (2003), [[Oxford University Press]], ISBN 0-19-262922-0</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:20, 20 September 2011

|

Pneumonia Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Hospital-acquired pneumonia On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Hospital-acquired pneumonia |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Hospital-acquired pneumonia |

Editor(s)-in-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Phone:617-632-7753; Philip Marcus, M.D., M.P.H.[2]

Overview

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or Health-Care associate pneumonia (HCAP) refers to any pneumonia contracted within 48-72 hours of being admitted in hospital. It is usually caused by a bacterial infection.[1][2]

Following urinary tract infections, this is the second common cause of nosocomial infections, and its prevalence is 15-20% of the total number.[1][2][3] It is the most common cause of death among nosocomial infections, while in the intensive care unit it is the primary cause of death.[1][3]

Hospital stay is generally 1 to 2 weeks longer than for other patients.[1][3]

Pathogenesis

Most nosocomial respiratory infections are caused by so-called skorvatch microaspiration of upper airway secretions, through inapparent aspiration, into the lower respiratory tract. Also, "macroaspirations" of esophageal or gastric material is known to result in HAP. Since it results from aspiration either type is called aspiration pneumonia.[1][2][3]

Although gram-negative bacilli are a common cause they are rarely found in the respiratory tract of people without pneumonia, which has led to speculation of the mouth and throat as origin of the infection.[1][2]

Etiology

The majority of cases related to various gram-negative bacilli(52%) and S. aureus (19%). Others are Haemophilus spp. (5%). In the ICU results were S. aureus(17.4%), P. aeruginosa (17.4%), Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp. (18.1%), and Haemophilus influenzae (4.9%).[1] Viruses -influenza and respiratory syncytial virus and, in the immunocompromised host, cytomegalovirus- cause 10-20% of infections.[2]

Risk factors

Among the factors contributing to contracting HAP are mechanical ventilation (ventilator-associated pneumonia), old age, decreased filtration of inspired air, intrinsic respiratory, neurologic, or other disease states that result in respiratory tract obstruction, trauma, (abdominal) surgery, medications, diminished lung volumes, or decreased clearance of secretions may diminish the defenses of the lung. Also poor hand-washing and inaqeuate disinfection of respiratory devicescauses cross-infection and is an important factor.[1][3]

Clinical Features

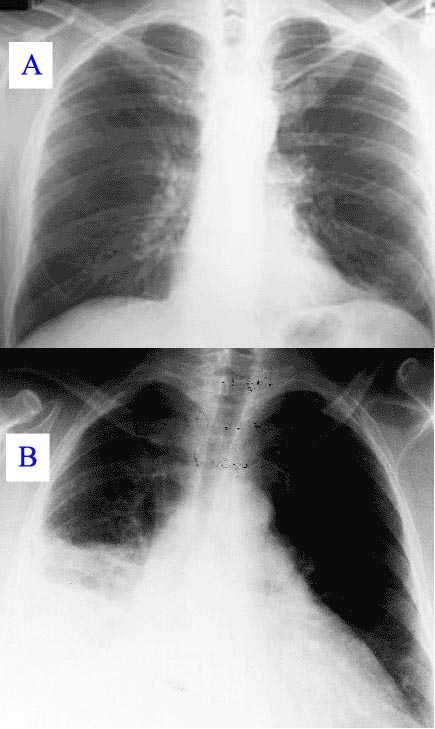

New or progressive infiltrate on the chest X-Ray with one of the following:[3]

- Fever > 37.8 °C (100 °F)

- Purulent sputum

- Leucocytosis > 10.000 cells/μl

Diagnosis

In hospitalised patient who develop respiratory symptoms and fever one should consider the diagnosis. The likelyhood increases when upon investigation symptoms are found of respiratory insufficiency, purulent secretions, newly developed infiltrate on the chest X-Ray, and increasing leucocyte count. If pneumonia is suspected material from sputum or tracheal aspirates are sent to the microbiology department for cultures. In case of pleural effusion thoracentesis is performed for examination of pleural fluid. In suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia it has been suggested that bronchoscopy(BAL) is necessary because of the known risks surrounding clinical diagnoses.[1][3]

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Usually initial therapy is empirical.[3] If sufficient reason to suspect influenza one might consider amantadine or rimantadine. In case of legionellosis erythromicin or fluoroquinolone.[1]

A third generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime) + carbapenems (imipenem) + beta lactam & beta lactamase inhibitors (piperacillin/tazobactum)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases 6th Edition (2004) by Gerald L. Mandell MD, MACP, John E. Bennett MD, Raphael Dolin MD, ISBN 0-443-06643-4 · Hardback · 4016 Pages Churchill Livingstone

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 The Oxford Textbook of Medicine Edited by David A. Warrell, Timothy M. Cox and John D. Firth with Edward J. Benz, Fourth Edition (2003), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-262922-0

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7