Endometrial cancer

For patient information click here

| Endometrial cancer | |

| |

|---|---|

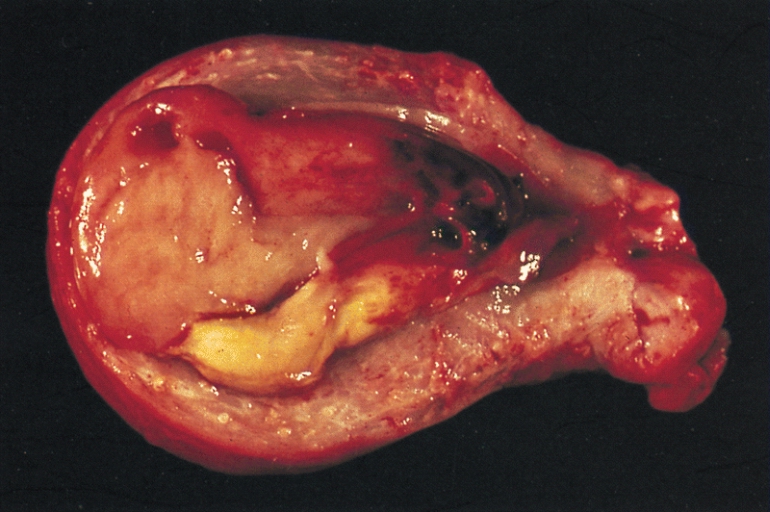

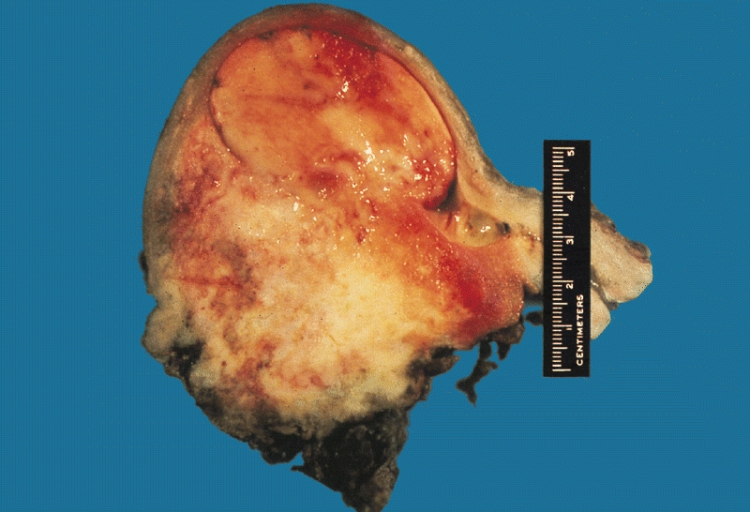

| An endometrial adenocarcinoma invading the uterine muscle | |

| ICD-10 | C54.1 |

| ICD-9 | 182 |

| OMIM | 608089 |

| DiseasesDB | 4252 |

| MedlinePlus | 000910 |

Template:Search infobox Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Endometrial cancer refers to several types of malignancy which arise from the endometrium, or lining of the uterus. Endometrial cancers are the most common gynecologic cancers in the United States, with over 35,000 women diagnosed each year in the U.S. The most common subtype, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, typically occurs within a few decades of menopause, is associated with excessive estrogen exposure, often develops in the setting of endometrial hyperplasia, and presents most often with vaginal bleeding. Because symptoms usually bring the disease to medical attention early in its course, endometrial cancer is only the third most common cause of gynecologic cancer death (behind ovarian and cervical cancer). A hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) is the most common therapeutic approach.

Endometrial cancer may sometimes be referred to as uterine cancer. However, different cancers may develop from other tissues of the uterus, including cervical cancer, sarcoma of the myometrium, and trophoblastic disease.

Epidemiology

Endometrial cancer occurs in both premenopausal (25%) and postmenopausal women (75%). The most commonly affected age group is between 50 and 59 years of age. Most tumors are caught early and thus prognosis is good and morbidity is declining.

Classification

Most endometrial cancers are carcinomas (usually adenocarcinomas), meaning that they originate from the single layer of epithelial cells which line the endometrium and form the endometrial glands. There are many microscopic subtypes of endometrial carcinoma, including the common endometrioid type, in which the cancer cells grow in patterns reminiscent of normal endometrium, and the far more aggressive papillary serous and clear cell endometrial carcinomas. Some authorities have proposed that endometrial carcinomas be classified into two pathogenetic groups:[1]

- Type I: These cancers occur most commonly in pre- and peri-menopausal women, often with a history of unopposed estrogen exposure and/or endometrial hyperplasia. They are often minimally invasive into the underlying uterine wall, are of the low-grade endometrioid type, and carry a good prognosis.

- Type II: These cancers occur in older, post-menopausal women, are more common in African-Americans, and are not associated with increased exposure to estrogen. They are typically of the high-grade endometrioid, papillary serous or clear cell types, and carry a generally poor prognosis

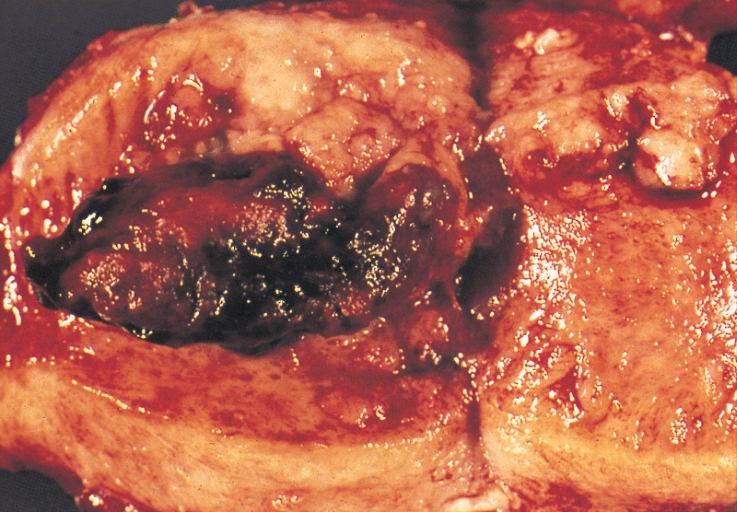

In contrast to endometrial carcinomas, the uncommon endometrial stromal sarcomas are cancers which originate in the non-glandular connective tissue of the endometrium. Malignant mixed müllerian tumor is a rare endometrial cancer which contains cancerous cells of both glandular and connective tissue appearance - in this case, the cell of origin is unknown.[2]

-

Endometrial stromal sarcoma

-

Malignant mixed müllerian tumor

Signs and Symptoms

- Abnormal uterine bleeding, abnormal menstrual periods

- Bleeding between normal periods in premenopausal women

- Vaginal bleeding and/or spotting in postmenopausal women

in women older than 40: extremely long, heavy, or frequent episodes of bleeding (may indicate premalignant changes)

- Anemia, caused by chronic loss of blood. (This may occur if the woman has ignored symptoms of prolonged or frequent abnormal menstrual bleeding.)

- Lower abdominal pain or pelvic cramping

- Thin white or clear vaginal discharge in postmenopausal women.

Causes

Most women with endometrial cancer have a history of unopposed and increased levels of estrogen. One of estrogen's normal functions is to stimulate the buildup of the endometrial lining of the uterus. Excess estrogen activity, especially in the setting of insufficient progesterone, may produce endometrial hyperplasia, which can be a precursor for cancer.

Increased estrogen may be due to:

- obesity (> 30 lb or 14 kg overweight)

- exogenous (medication)

The incidence of endometrial cancer in women in the U.S. is 1 % to 2 %. The incidence peaks between the ages of 60 and 70 years, but 2 % to 5 % of cases may occur before the age of 40 years. Increased risk of developing endometrial cancer has been noted in women with increased levels of natural estrogen.

Associated conditions include the following:

Increased risk is also associated with the following:

- nulliparity (never having carried a pregnancy)

- infertility (inability to become pregnant)

- early menarche (onset of menstruation)

- late menopause (cessation of menstruation)

Women who have a history of endometrial polyps or other benign growths of the uterine lining, postmenopausal women who use estrogen-replacement therapy (specifically if not given in conjunction with periodic progestin) and those with diabetes are also at increased risk.

Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat breast cancer, can also increase the risk of developing endometrial cancer.

The same risk factors predisposes women to endometrial hyperplasia, which is a precursor lesion for endometrial carcinoma. An atypical complex hyperplasia carries a 30% risk of developing endometrial carcinoma, while a typical simple hyperplasia only carries a 2-3% risk.

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation

Routine screening of asymptomatic women is not indicated, since the disease is highly curable in its early stages. Results from a pelvic examination are frequently normal, especially in the early stages of disease. Changes in the size, shape or consistency of the uterus and/or its surrounding, supporting structures may exist when the disease is more advanced.

- A Pap smear may be either normal or show abnormal cellular changes.

- Endometrial curettage is the traditional diagnostic method. Both endometrial and endocervical material should be sampled.

- If endometrial curettage does not yield sufficient diagnostic material, a dilation and curettage (D&C) is necessary for diagnosing the cancer.

- Endometrial biopsy or aspiration may assist the diagnosis.

- Transvaginal ultrasound to evaluate the endometrial thickness in women with postmenopausal bleeding is increasingly being used to evaluate for endometrial cancer.

- Recently, a new method of testing has been introduced called the TruTest, offered through Gynecor. It uses the small flexible Tao Brush to brush the entire lining of the uterus. This method is less painful than a pipelle biopsy and has a larger likelihood of procuring enough tissue for testing. Since it is simpler and less invasive, the TruTest can be performed as often, and at the same time as, a routine Pap smear, thus allowing for early detection and treatment.

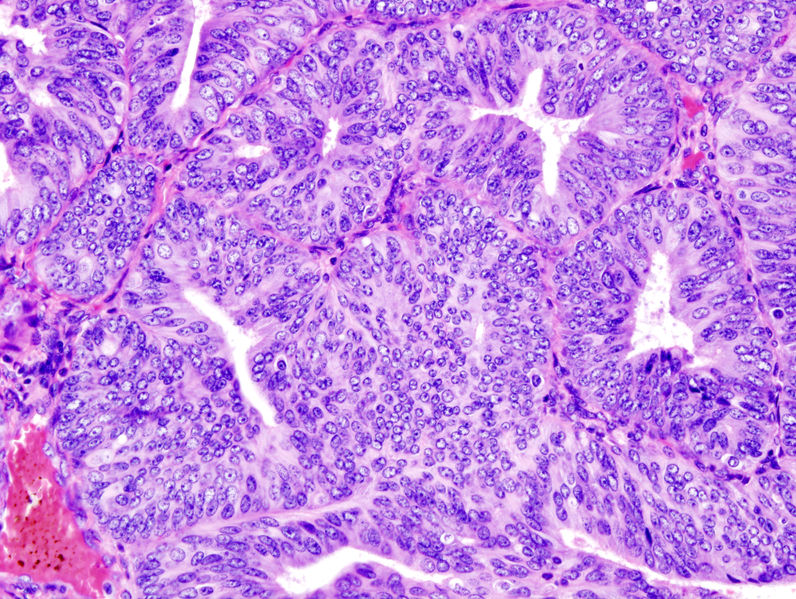

Pathology

The histopathology of endometrial cancers is highly diverse. The most common finding is a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is composed of numerous, small, crowded glands with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and stratification. This often appears on a background of endometrial hyperplasia. Frank adenocarcinoma may be distinguished from atypical hyperplasia by the finding of clear stromal invasion, or "back-to-back" glands which represent nondestructive replacement of the endometrial stroma by the cancer. With progression of the disease, the myometrium is infiltrated.[2]

Further evaluation

Patients with newly-diagnosed endometrial cancer do not routinely undergo imaging studies, such as CT scans to evaluate for extent of disease, since this is of low yield. Preoperative evaluation should include a complete medical history and physical examination, pelvic examination and rectal examination with stool guaiac test, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and blood chemistry tests, including liver function tests. Colonoscopy is recommended if the stool is guaiac positive or the woman has symptoms, due to the etiologic factors common to both endometrial cancer and colon cancer. The tumor marker CA-125 is sometimes checked, since this can predict advanced stage disease.[3]

Staging

Endometrial carcinoma is surgically staged using the FIGO cancer staging system.

- Stage IA: tumor is limited to the endometrium

- Stage IB: invasion of less than half the myometrium

- Stage IC: invasion of more than half the myometrium

- Stage IIA: endocervical glandular involvement only

- Stage IIB: cervical stromal invasion

- Stage IIIA: tumor invades serosa or adnexa, or malignant peritoneal cytology

- Stage IIIB: vaginal metastasis

- Stage IIIC: metastasis to pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes

- Stage IVA: invasion of the bladder or bowel

- Stage IVB: distant metastasis, including intraabdominal or inguinal lymph nodes

Treatment

The primary treatment is surgical. Surgical treatment should consist of, at least, cytologic sampling of the peritoneal fluid, abdominal exploration, palpation and biopsy of suspicious lymph nodes, abdominal hysterectomy, and removal of both ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Lymphadenectomy, or removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, is sometimes performed for tumors that have high risk features, such as pathologic grade 3 serous or clear-cell tumors, invasion of more than 1/2 the myometrium, or extension to the cervix or adnexa. Sometimes, removal of the omentum is also performed.

Abdominal hysterectomy is recommended over vaginal hysterectomy because it affords the opportunity to examine and obtain washings of the abdominal cavity to detect any further evidence of cancer.

Women with stage 1 disease who are at increased risk for recurrence and those with stage 2 disease are often offered surgery in combination with radiation therapy. Chemotherapy may be considered in some cases, especially for those with stage 3 and 4 disease. hormonal therapy with progestins and antiestrogens has been used for the treatment of endometrial stromal sarcomas.[4]

Complications of treatment

- A perforation (hole) of the uterus may occur during a D&C or an endometrial biopsy.

Support Groups

The stress of illness can often be helped by joining a support group where members share common experiences and problems.

Prognosis

Because endometrial cancer is usually diagnosed in the early stages (70 % to 75 % of cases are in stage 1 at diagnosis; 10 % to 15 % of cases are in stage 2; 10 % to 15 % of cases are in stage 3 or 4), there is a better probable outcome associated with it than with other types of gynecological cancers such as cervical or ovarian cancer. While endometrial cancers are 40% more common in Caucasian women, an African American woman who is diagnosed with uterine cancer is twice as likely to die, possibly due to the higher frequency of aggressive subtypes in that population.

Survival rates

The 5-year survival rate for endometrial cancer following appropriate treatment is:

- 75% to 95% for stage 1

- 50% for stage 2

- 30% for stage 3

- less than 5% for stage 4

References

- ↑ Bokhman JV (1983). "Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma". Gynecol. Oncol. 15 (1): 10–7. PMID 6822361.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Richard Cote, Saul Suster, Lawrence Weiss, Noel Weidner (Editor). Modern Surgical Pathology (2 Volume Set). London: W B Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-7253-1.

- ↑ Dotters DJ. Preoperative CA 125 in endometrial cancer: is it useful? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:1328-34. PMID 10871446.

- ↑ [1] American Cancer Society - Uterine Sarcomas - Hormonal Therapy (accessed 5-25-07)

External links

de:Korpuskarzinom no:Livmorkreft