Pericarditis in malignancy

|

Pericarditis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Surgery |

|

Case Studies |

|

Pericarditis in malignancy On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Pericarditis in malignancy |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Pericarditis in malignancy |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Varun Kumar, M.B.B.S.; Lakshmi Gopalakrishnan, M.B.B.S.

Overview

Many malignant neoplasms such as lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, lymphomas, melanomas, kaposi's sarcoma and leukemias may metastasize to pericardium causing pericarditis, effusion, cardiac tamponade and pericardial constriction. Malignant pericardial effusion is seen in approximately 50-60% of patients presenting with pericardial effusion who have history of malignancy[1][2]. Among patients presenting with pericarditis or pericardial effusion with no history of malignancy, undiagnosed underlying malignancy was detected in 4-7%[3][4][5].

Malignancy related pericardial disease can manifest as pericarditis, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade or pericardial constriction.

Epidemiology and demographics

In developed countries malignancy is the leading cause of cardiac tamponade secondary to pericardial effusion. Malignant pericardial effusion is seen in approximately 50-60% of patients presenting with pericardial effusion who have history of malignancy[1][2]. Among patients presenting with pericarditis or pericardial effusion with no history of malignancy, undiagnosed underlying malignancy was detected in 4-7%[3][4][5].

Carcinoma of the lung is the most common cause for pericardial effusion in malignancy accounting for approximately 40%. Another 40% of cases could be due to breast carcinoma and lymphomas. Carcinoma of GI tract, melanoma, sarcomas, and other neoplastic diseases are less common.

Kaposi sarcoma and lymphomas associated with HIV were other neoplastic causes of pericardial effusion which accounted for 5% and 7% respectively[6] in one study and 15% together[7] in another series. However, with the use of antiretroviral agents, the incidence of Kaposi carcinoma and subsequent pericardial effusion has considerably decreased.

In regions where tuberculosis is not highly prevalent, malignancy may be the most common cause of a hemorrhagic effusion[8][9]

Sex

Higher incidence of the pericardial effusion related to malignancy is observed among males with ratio of 7:3 as reported in a series[10]

Natural history, prognosis and complications

Gaurded prognosis associated with malignancies is worsened by pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Children may have poor prognosis and thus, prompt detection and treatment of cardiac tamponade improves survival[11][12].

Patients rarely present with cardiac tamponade as their first presentation. Superior vena cava syndrome may occur in few secondary to either coexisting tumor or rapid accumulation of pericardial effusion[13].

Prognosis of symptomatic malignant pericardial disease is grave with a short life expectancy of 2-4 months[14][15][16][17]. While the patients with hematologic[18] or breast cancer[19], or those in whom malignant cells are not present in pericardium[20] have better prognosis in comparison to those with solid tumors, lung cancer[21], etc.

Pathophysiology

Pericardium may be involved by direct local spread from neoplasms such as breast and lung carcinomas or by metastatic spread via blood stream and lymphatics as in melanomas, lymphomas and leukemias.

Pericardial effusion in such situations may occur either secondary to pericardial inflammation or obstruction of lymphatic drainage by enlarged mediastinal nodes[22][11][5].

Etiology

- Pericardial mesothelioma

- Fibrosarcoma

- Wilms tumor

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Primary mediastinal (thymic) B-cell lymphoma

- Adenocarcinoma

- Angiosarcoma

- Sarcomas

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Liposarcoma

- Pheochromocytoma

- Lymphoma

- Malignant pericardial teratoma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma with tuberous sclerosis

- Pheochromocytoma

- Neuroblastoma

- Ganglioneuroblastoma

- Leiomyosarcomas

- Liposarcomas

- High-grade sarcomas

- Burkitt lymphoma

- Kaposi sarcoma and primary cardiac lymphoma in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

- Intrapericardial teratoma in the fetus and neonate

Diagnosis

History and symptoms

In addition to malignancy specific presentation, patients may present with the following symptoms due to pericardial involvement:

- Fever

- Chest pain that improves on leaning forward and worsens on inspiration

- Breathlessness

- Orthopnoea

- Dizziness

- Palpitation

- Malaise

- Ankle edema

- Weight loss

Many patients may be asymptomatic and pericardial involvement may be detected incidentally on chest x-ray or on autopsy.

Physical examination

Cachexia, weight loss and other organ-system specific abnormalities secondary to malignancy.

Vitals: Tachycardia, pulsus paradoxus and hypotension(in cardiac tamponade)

Neck: Jugular venous distension with a prominent Y descent and Kussmaul's sign

Chest: Pericardial knock, pericardial rub and distant heart sounds

Abdomen: Hepatomegaly, ascites

Extremities: Ankle edema

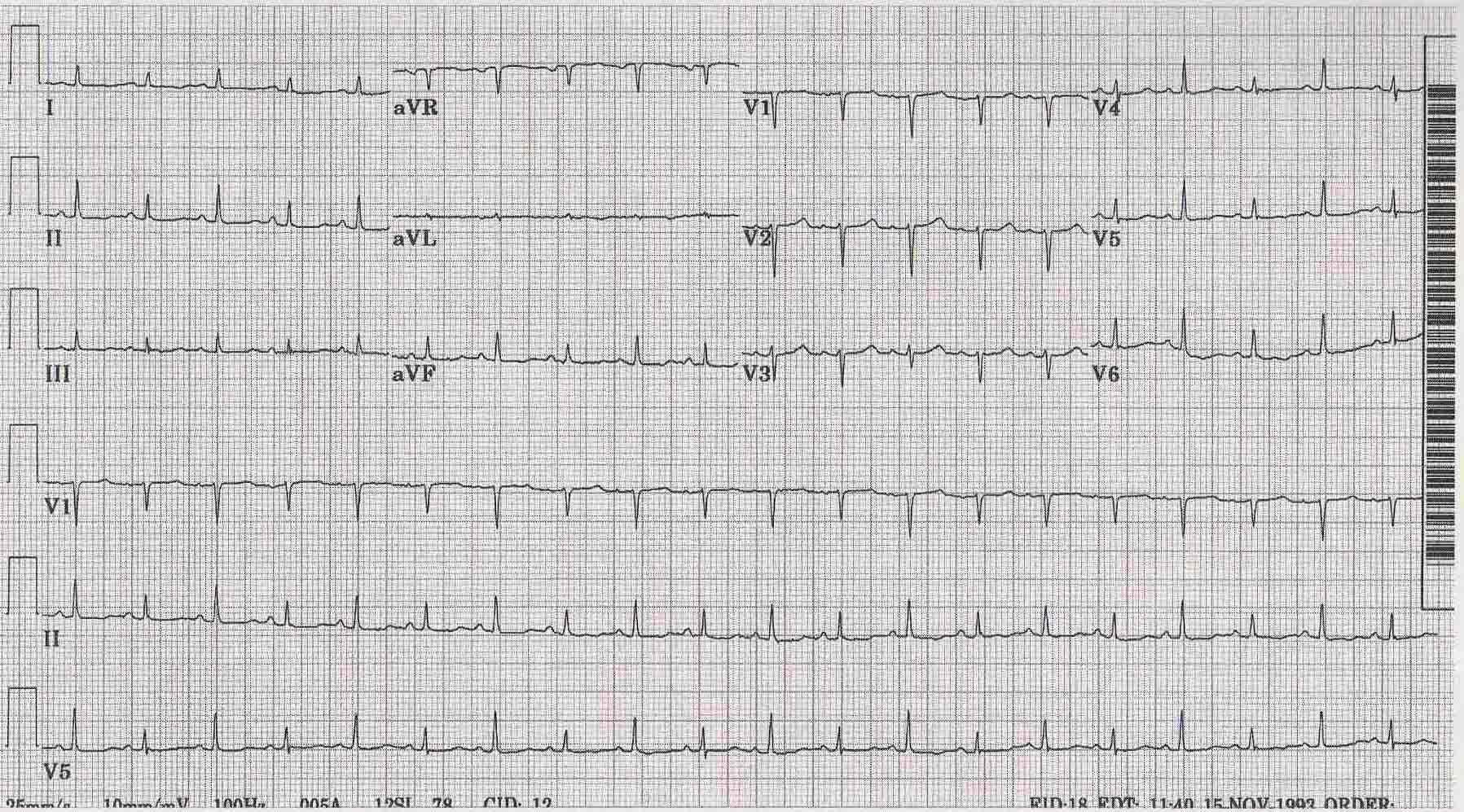

Electrocardiography

- Characteristic ST elevations with PR depression may be noted in all leads in presence of pericarditis.

- In case of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade, micro-voltage with electical alternans may be observed which could be due to swinging motion of heart in pool of pericardial fluid.

- Constrictive pericarditis may present with ECG changes consistent with atrial fibrillation.

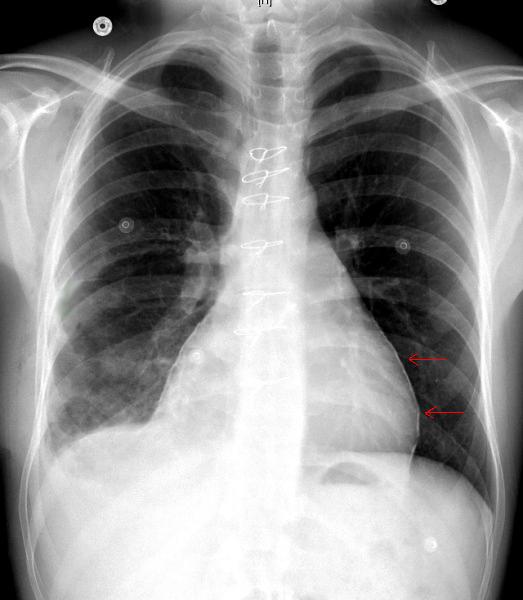

Chest X-ray

Enlarged cardiac silhouette may be noted in pericardial effusion. Pericardial calcifications may be noted in constrictive pericarditis

Echocardiography

Echocardiography facilitates in visualizing the fluid accumulation within the pericardial cavity. Pericardial or myocardial tumors if present can also be noted.

Echocardiogram demonstrating Pericardial effusion and Myocardial tumor <youtube v=sGTttwrx2xw/>

MRI and CT

MRI and CT of chest and abdomen helps us in visualizing the presence of tumor/malignancy and the degree of metastasis to other parts of the body in addition to pericardial involvement. They are superior to echocardiography[23] in terms of providing information about whether an effusion is hemorrhagic or loculated and also in differentiating hematoma from tumor.

Pericardiocentesis

Pericardial fluid should be aspirated and tested for presence of malignant cells and tumor markers particularly in patients with hemorrhagic effusion without preceding trauma[9]. However, hemorrhagic pericarditis in developing countries could be due to tuberculosis. Sensitivity of cytological analysis of pericardial fluid for malignant cells were 67%[24], 75%[2] and 92%[25] in different studies with specificity of 100%. Immunohistochemistry can be used to distinguish between the malignant cells and their possible origin[26][27].

Pericardial biopsy

Negative cytology should be followed with by pericardial biopsy performed via a subxiphoid or transthoracic pericardiostomy or by pericardioscopy. The pericardioscopy which helps in direct visualization of pericardium and collecting biopsy sample, has a good sensitivity of 97%[2][28] when compared to blind biopsy which has a low sensitivity of 55-65%.

Cardiac catheterization

- Cardiac tamponade: There is equalization of pressures in all four chambers of heart. The right atrial pressure equals the right ventricular end diastolic pressure equals the pulmonary artery diastolic pressure.

- Constrictive pericarditis: Equalization of elevated right atrial and pulmonary artery wedge pressures may be noted with a diastolic dip and plateau in the right ventricular tracing.

- Effusive constrictive pericarditis: Cardiac tamponade findings are noted initially. Findings of constrictive pericarditis are unmasked following pericardiocentesis.

Treatment

It is important to assess the life expectancy of the patients before proceeding with the treatment. Patients with advanced malignancy should be treated palliatively with pericardiocentesis to improve their symptoms. While those with better prognosis should be treated more aggressively.

Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients should be treated conservatively with avoidance of volume depletion, antineoplastic therapy and regular followup.

Symptomatic patients should undergo prompt drainage of effusion which could be done either by pericardiocentesis or surgical creation of pericardial window.

Recurrence of pericardial effusion is frequently observed following simple pericardiocentesis[14][29]. Following approaches are adapted in prevention of reaccumulation:

- Prolonged pericardiocentesis:[14][30] Catheter should not be removed until the drainage is <20-30 ml/24 hours. Intermittent catheterization is recommended to maintain catheter patency.

- Pericardial sclerosis: Obliteration of pericardial cavity using tetracycline, doxycycline[31], minocycline[32], bleomycin[33], or talc.

- Pericardiotomy: Surgical creation of pericardial window which drains fluid into pleural or peritoneal cavity as fluid accumulates in pericardial sac.In presence of hemodynamic instability, pericardial fluid must be removed first by pericardiocentesis and then proceed with with surgery. To a large extent this avoids further instability or cardiovascular collapse during induction of general anesthesia[34].

Patients with constrictive pericarditis should be treated with pericardial stripping also known as pericardiectomy provided that the prognosis from the malignancy justifies surgery. It is not recommended in patients with mild constriction and in advanced stages of malignancy due to operative risk of 6-12%[35][36].

Intrapericardial chemotherapy is another approach in treatment of recurrent effusion. Cisplatin has shown to reduce the incidence of recurrence by up to 93% at 3months and 83% at 6 months followup[8][37].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gornik HL, Gerhard-Herman M, Beckman JA (2005). "Abnormal cytology predicts poor prognosis in cancer patients with pericardial effusion". J Clin Oncol. 23 (22): 5211–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.00.745. PMID 16051963.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Porte HL, Janecki-Delebecq TJ, Finzi L, Métois DG, Millaire A, Wurtz AJ (1999). "Pericardoscopy for primary management of pericardial effusion in cancer patients". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 16 (3): 287–91. PMID 10554845.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Permanyer-Miralda G, Sagristá-Sauleda J, Soler-Soler J (1985). "Primary acute pericardial disease: a prospective series of 231 consecutive patients". Am J Cardiol. 56 (10): 623–30. PMID 4050698.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, Ierna S, Demarie D, Ghisio A; et al. (2007). "Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis". Circulation. 115 (21): 2739–44. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662114. PMID 17502574.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, Favro E, Beqaraj F, Cecchi E; et al. (2005). "Relation of acute pericardial disease to malignancy". Am J Cardiol. 95 (11): 1393–4. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.094. PMID 15904655.

- ↑ Chen Y, Brennessel D, Walters J, Johnson M, Rosner F, Raza M (1999). "Human immunodeficiency virus-associated pericardial effusion: report of 40 cases and review of the literature". Am Heart J. 137 (3): 516–21. PMID 10047635.

- ↑ Gowda RM, Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Gowda MR, Sacchi TJ, Vasavada BC (2003). "Cardiac tamponade in patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease". Angiology. 54 (4): 469–74. PMID 12934767.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Maisch B, Ristic A, Pankuweit S (2010). "Evaluation and management of pericardial effusion in patients with neoplastic disease". Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 53 (2): 157–63. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2010.06.003. PMID 20728703.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Atar S, Chiu J, Forrester JS, Siegel RJ (1999). "Bloody pericardial effusion in patients with cardiac tamponade: is the cause cancerous, tuberculous, or iatrogenic in the 1990s?". Chest. 116 (6): 1564–9. PMID 10593777.

- ↑ Medary I, Steinherz LJ, Aronson DC, La Quaglia MP (1996). "Cardiac tamponade in the pediatric oncology population: treatment by percutaneous catheter drainage". J Pediatr Surg. 31 (1): 197–9, discussion 199-200. PMID 8632279.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ben-Horin S, Bank I, Guetta V, Livneh A (2006). "Large symptomatic pericardial effusion as the presentation of unrecognized cancer: a study in 173 consecutive patients undergoing pericardiocentesis". Medicine (Baltimore). 85 (1): 49–53. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000199556.69588.8e. PMID 16523053.

- ↑ Bień E, Stefanowicz J, Aleszewicz-Baranowska J, Połczyńska K, Szołkiewicz A, Stachowicz-Stencel T; et al. (2005). "[Cardio-vascular disorders at the time of diagnosis of malignant solid tumours in children--own experiences]". Med Wieku Rozwoj. 9 (3 Pt 2): 551–9. PMID 16719168.

- ↑ Tsai MH, Yang CP, Chung HT, Shih LY (2009). "Acute myeloid leukemia in a young girl presenting with mediastinal granulocytic sarcoma invading pericardium and causing superior vena cava syndrome". J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 31 (12): 980–2. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181b86ff3. PMID 19956024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Tsang TS, Seward JB, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Sinak LJ, Urban LH; et al. (2000). "Outcomes of primary and secondary treatment of pericardial effusion in patients with malignancy". Mayo Clin Proc. 75 (3): 248–53. PMID 10725950.

- ↑ Gross JL, Younes RN, Deheinzelin D, Diniz AL, Silva RA, Haddad FJ (2006). "Surgical management of symptomatic pericardial effusion in patients with solid malignancies". Ann Surg Oncol. 13 (12): 1732–8. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9073-1. PMID 17028771.

- ↑ Cullinane CA, Paz IB, Smith D, Carter N, Grannis FW (2004). "Prognostic factors in the surgical management of pericardial effusion in the patient with concurrent malignancy". Chest. 125 (4): 1328–34. PMID 15078742.

- ↑ Dequanter D, Lothaire P, Berghmans T, Sculier JP (2008). "Severe pericardial effusion in patients with concurrent malignancy: a retrospective analysis of prognostic factors influencing survival". Ann Surg Oncol. 15 (11): 3268–71. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0059-z. PMID 18648881.

- ↑ Dosios T, Theakos N, Angouras D, Asimacopoulos P (2003). "Risk factors affecting the survival of patients with pericardial effusion submitted to subxiphoid pericardiostomy". Chest. 124 (1): 242–6. PMID 12853529.

- ↑ Girardi LN, Ginsberg RJ, Burt ME (1997). "Pericardiocentesis and intrapericardial sclerosis: effective therapy for malignant pericardial effusions". Ann Thorac Surg. 64 (5): 1422–7, discussion 1427-8. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00992-2. PMID 9386714.

- ↑ Neragi-Miandoab S, Linden PA, Ducko CT, Bueno R, Richards WG, Sugarbaker DJ; et al. (2008). "VATS pericardiotomy for patients with known malignancy and pericardial effusion: survival and prognosis of positive cytology and metastatic involvement of the pericardium: a case control study". Int J Surg. 6 (2): 110–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.12.005. PMID 18329349.

- ↑ García-Riego A, Cuiñas C, Vilanova JJ (2001). "Malignant pericardial effusion". Acta Cytol. 45 (4): 561–6. PMID 11480719.

- ↑ Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y; et al. (2004). "Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology". Eur Heart J. 25 (7): 587–610. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002. PMID 15120056.

- ↑ Bellon RJ, Wright WH, Unger EC (1995). "CT-guided pericardial drainage catheter placement with subsequent pericardial sclerosis". J Comput Assist Tomogr. 19 (4): 672–3. PMID 7622713.

- ↑ Wiener HG, Kristensen IB, Haubek A, Kristensen B, Baandrup U (1991). "The diagnostic value of pericardial cytology. An analysis of 95 cases". Acta Cytol. 35 (2): 149–53. PMID 2028688.

- ↑ Meyers DG, Meyers RE, Prendergast TW (1997). "The usefulness of diagnostic tests on pericardial fluid". Chest. 111 (5): 1213–21. PMID 9149572.

- ↑ Gong Y, Sun X, Michael CW, Attal S, Williamson BA, Bedrossian CW (2003). "Immunocytochemistry of serous effusion specimens: a comparison of ThinPrep vs cell block". Diagn Cytopathol. 28 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1002/dc.10219. PMID 12508174.

- ↑ Mayall F, Heryet A, Manga D, Kriegeskotten A (1997). "p53 immunostaining is a highly specific and moderately sensitive marker of malignancy in serous fluid cytology". Cytopathology. 8 (1): 9–12. PMID 9068950.

- ↑ Nugue O, Millaire A, Porte H, de Groote P, Guimier P, Wurtz A; et al. (1996). "Pericardioscopy in the etiologic diagnosis of pericardial effusion in 141 consecutive patients". Circulation. 94 (7): 1635–41. PMID 8840855.

- ↑ Laham RJ, Cohen DJ, Kuntz RE, Baim DS, Lorell BH, Simons M (1996). "Pericardial effusion in patients with cancer: outcome with contemporary management strategies". Heart. 75 (1): 67–71. PMC 484225. PMID 8624876.

- ↑ Allen KB, Faber LP, Warren WH, Shaar CJ (1999). "Pericardial effusion: subxiphoid pericardiostomy versus percutaneous catheter drainage". Ann Thorac Surg. 67 (2): 437–40. PMID 10197666.

- ↑ Liu G, Crump M, Goss PE, Dancey J, Shepherd FA (1996). "Prospective comparison of the sclerosing agents doxycycline and bleomycin for the primary management of malignant pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade". J Clin Oncol. 14 (12): 3141–7. PMID 8955660.

- ↑ Davis S, Rambotti P, Grignani F (1984). "Intrapericardial tetracycline sclerosis in the treatment of malignant pericardial effusion: an analysis of thirty-three cases". J Clin Oncol. 2 (6): 631–6. PMID 6726303.

- ↑ Kunitoh H, Tamura T, Shibata T, Imai M, Nishiwaki Y, Nishio M; et al. (2009). "A randomised trial of intrapericardial bleomycin for malignant pericardial effusion with lung cancer (JCOG9811)". Br J Cancer. 100 (3): 464–9. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604866. PMC 2658533. PMID 19156149.

- ↑ DeCamp MM, Mentzer SJ, Swanson SJ, Sugarbaker DJ (1997). "Malignant effusive disease of the pleura and pericardium". Chest. 112 (4 Suppl): 291S–295S. PMID 9337306.

- ↑ Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, Danielson GK, Mahoney DW, Seward JB; et al. (1999). "Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy". Circulation. 100 (13): 1380–6. PMID 10500037.

- ↑ DeValeria PA, Baumgartner WA, Casale AS, Greene PS, Cameron DE, Gardner TJ; et al. (1991). "Current indications, risks, and outcome after pericardiectomy". Ann Thorac Surg. 52 (2): 219–24. PMID 1863142.

- ↑ Maisch B, Ristić AD, Pankuweit S, Neubauer A, Moll R (2002). "Neoplastic pericardial effusion. Efficacy and safety of intrapericardial treatment with cisplatin". Eur Heart J. 23 (20): 1625–31. PMID 12323163.