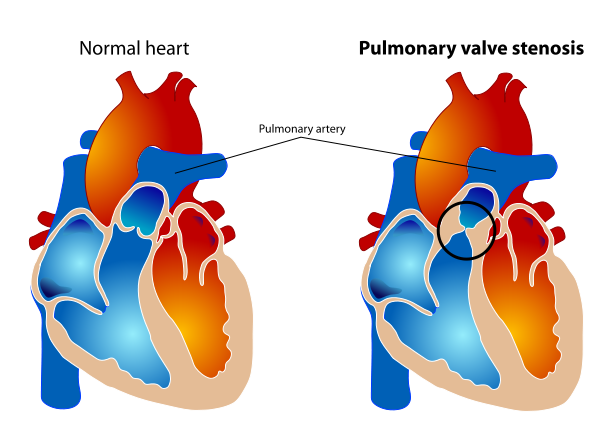

Pulmonary valve stenosis

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | |

| |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | |

| ICD-10 | I37.0, I37.2, Q22.1 |

| ICD-9 | 424.3, 746.02 |

| OMIM | 265500 |

| DiseasesDB | 11025 |

| MedlinePlus | 001096 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aravind Kuchkuntla, M.B.B.S[2]

Synonyms and keywords: Valvular Pulmonary Stenosis, Pulmonic Stenosis, Right Ventricular Outlet Obstruction, supravalvular pulmonic stenosis, infundibular pulmonic stenosis, RVOT, congenital pulmonary valve stenosis, Congenital stenosis of pulmonary valve, Narrowing of pulmonary valve

Overview

Pulmonary stenosis accounts for 8% of all congenital heart disease and worldwide the prevalence of pulmonic stenosis is 1 per 2000 births.[1] The pulmonic valve stenosis is classified into 3 different subtypes based on the location of the stenosis. Isolated valvular stenosis is the most common sub-type, with dome shaped morphology and dysplastic valves. Patients with mild stenosis usually have a beningn course and do not progress, patients with moderate to severe stenosis manifest symptoms of dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue and syncope. If left untreated patients progress to right heart failure. 2D Echo is the standard diagnostic test to identify the location and to assess the severity of the stenosis. Symptomatic patients undergo valvulotomy or balloon valvuloplasty based on the morphology of the affected valves. Timely intervention in patients with valvular stenosis has good outcomes and excellent prognosis. Guidelines for evaluation, approach and treatment are well-defined.

Historical Perspective

- The pulmonary valve and its function of allowing blood to the lungs for nourishment was first described by Hippocrates.[2]

- Erasistratus, mentioned the involvement of the pulmonary valve in the unidirectional flow.

- Galen described the membranes of the valves and named them as "semilunar".

- Mondino de Luzzi designed the sketch of the pulmonary valves in the anatomical position for the first time.

- Realdo Colombo described the pulmonary circulation for the first time.

Classification

Based on the anatomic location

Pulmonic stenosis is classified into valvular, subvalvular (infundibular) and supravalvular based on the location of the stenosis in relation to the pulmonary valve. Valvular stenosis is most common of the three sub-types.

- Sub-valvular stenosis: It can be infudibular or sub-infundibular. Infundibular stenosis is a feature of tetralogy of fallot. Sub-infundibular pulmonic stenosis is known as ‘double chambered right ventricle’ dividing the right ventricle into a high pressure inlet and a low pressure outlet causing a progressive right ventricular outflow tract obstruction.[3]

- Valvular stenosis: It is the most common cause of pulmonic stenosis. The valves are usually dome shaped or dysplastic affecting the movement of the cusps. It can be isolated or associated with other congenital heart diseases such as atrial septal defects, Ebstein’s anomaly, double outlet right ventricle, and transposition of the great arteries.

- Supravalvular stenosis: The obstruction is usually in the common pulmonary trunk or in the bifurcation or the pulmonary branches. It is commonly associated with other congenital syndromes such as Williams–Beuren, Noonan, Allagile, DiGeorge, and Leopard syndrome.

Based on the severity of the stenosis

Severity of pulmonary stenosis is classified based on the estimated peak velocity and peak resting gradient calculated using modified Bernoulli equation. It is classified into:[4]

- Mild: Peak velocity less than 3m/s and peak gradient is less than 36 mm Hg.

- Moderate: Peak velocity is 3 to 4m/s and peak gradient is 36 to 64mm Hg.

- Severe: Peak velocity is greater than 4m/s and peak gradient is greater than 64mm Hg.

- According to 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease, stages of severe pulmonic stenosis is defined as follows:[5]

| Stage | Definition | Valve Anatomy | Valve Hemodynamics | Hemodynamic Consequences | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C,D | Severe pulmonic stenosis |

|

|

|

|

- According to 2014 AHA/ACC Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease, progression of valvular heart disease (VHD) are defined as follows:[6]

| Stage | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A | At risk | Patients with risk factors for development of VHD |

| B | Progressive | Patients with progressive VHD (mild-to-moderate severity and asymptomatic) |

| C | Asymptomatic severe | Asymptomatic patients who have the criteria for severe VHD:

C1: Asymptomatic patients with severe VHD in whom the left or right ventricle remains compensated C2: Asymptomatic patients with severe VHD with decompensation of the left or right ventricle |

| D | Symptomatic severe | Patients who have developed symptoms as a result of VHD |

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- Pulmonic valve stenosis with fused commisures affect the flexibility of the valve causing obstruction of the outflow tract. In patients with dysplastic valves, the cusps are not fused but they are rigid from intrinsic thickening resulting in the narrowing of the outflow tract.[7]

- These morphological changes affect the complete opening of the pulmonic valve in ventricular systole causing elevated right ventricular systolic pressures and leading to right ventricular remodelling.[8]

- The obstruction leads to increased pressure overload in the right ventricle as it has to push the blood against resistance.

Genetics

These are a common genetic disorders associated with pulmonic stenosis:[9]

| Syndrome | Genetic Defect | Cardiac features | Other features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noonan[10] |

|

|

|

| Williams Beuren[11] |

|

|

|

| Leopard[12] |

|

|

|

| DiGeorge[14] |

|

|

|

| Allagile[15] |

|

|

|

| Keutel[17] |

|

|

|

| Congenital Rubella[18] | N/A |

|

|

Associated conditions

A rare association of pulmonic stenosis with an unrepaired ASD is reported.[19]

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Pulmonary stenosis accounts for 8% of all congenital heart disease.

- Worldwide, the prevalence of pulmonic stenosis is 1 per 2000 births.[1]

- The prevalence of pulmonic stenosis and tetralogy of fallot is higher in asian countries.[20]

Causes

Pulmonary valve stenosis is due to a structural changes resulting from thickening and fusion of the pulmonary valve. The valve pathology can be congenital or acquired. The following is the list of causes:

Congenital causes

These account for 95% of the cases with pulmonic stenosis which include isolated pulmonic valve pathologies and its associations with other congenital heart diseases.[21]

Associated with congenital heart disease

- Tetralogy of Fallot[22]

- Double outlet right ventricle

- Univentricular atrio-ventricular connection

- Atrioventricular canal defect

- Bicuspid pulmonary valve[23]

- Quadricuspid pulmonary valve: Benign and an incidental finding.[24]

- Isolated pulmonic stenosis[25]

- Acommissural pulmonary valves: Valve has a prominent systolic doming of the cusps and an eccentric orifice.[26][27]

- Dysplastic pulmonary valves: Thickened and deformed cusps with no commissural fusion.[28] It is a common finding associated with Noonan syndrome.[29]

- Unicommissural pulmonary valve

- Bicuspid valve with fused commissures.

Acquired Causes

These are less frequent and account for less than 5% of the cases

- Carcinoid Syndrome: most common acquired cause[30][31][32]

- Post infectious: Infective endocarditis

- Calcification of the pulmonary valve[33]

- Rheumatic heart disease[34]

- Ross procedure[35]

- Functional Pulmonic Stenosis: Primary cardiac tumours obstructing the right ventricular outflow tract such as leiomyosarcoma.[36]

Differentiating from other diseases

Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction must be distinguished from an ASD, a small VSD, aortic stenosis, and acyanotic or pink tetralogy of Fallot.

- Atrial septal defect: Presence of systolic ejection murmur, wide fixed split S2, EKG showing RVH. In ASD the split of the S2 is fixed, there is no ejection click.

- Small Ventricular septal defect: Amyl nitrate increases venous return and increases the murmur of pulmonary stenosis, in VSD the murmur becomes softer.

- Mild left-sided outflow obstruction: With valsalva maneuver the murmur of aortic stenosis becomes softer after about 5 beats, with pulmonary stenosis it becomes softer within 3 beats.

- Acyanotic or pink tetralogy of Fallot: with amyl nitrate and increased venous return the murmur of PS increases, and the murmur of tetralogy decreases because of peripheral dilation and an increase in right to left shunting.

Risk Factors

Common risk factors in the development of congenital heart disease apply for pulmonic stenosis and include:[37]

- Maternal gestational diabetes mellitus

- Consanguineous marriage[38]

- Phenylketonuria

- Febrile illness

- Vitamin A use

- Marijuana use

- Exposure to organic solvents

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Natural History

Patients with congenital pulmonary stenosis manifest clinical features few hours after birth, in childhood or in adulthood. Manifestation of symptoms, symptom severity and the outcomes are dependent on the severity of the disease.[39] Patients with mild pulmonic stenosis have a benign course and do not progress.[40] and patients with moderate and severe stenosis have dyspnea with exertion and syncope.

Prognosis

Patients with moderate to severe pulmonic valve stenosis are managed well with surgery or balloon valvuloplasty and have very good prognosis.

Complications

If left untreated, patients with moderate to severe stenosis progress to develop tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular dysfunction leading to right ventricular failure and arrhythmias.[41]

Diagnosis

Gold standard diagnosis of pulmonic stenosis and assessment of severity is done by 2D echocardiography.[42]

History and Symptoms

The severity of symptoms and age of symptom onset depends on the severity of the stenosis. Clinical presentations vary as follows:

- Critical pulmonary stenosis:It presents in first few hours to days of life with cyanosis. It is a condition with a very small or pin-hole orifice in the pulmonary valve which can be diagnosed prenatally. These patients have an intact interventricular septum, poorly complaint hypoplastic right ventricle and are ductus dependent. Cyanosis in these patients is due to the right to left shunting at the level of the foramen ovale.[43][44]

- Mild Pulmonic Stenosis: Patients with mild stenosis are asymptomatic and are diagnosed by routine examination with an ejection systolic murmur.

- Moderate Pulmonic Stenosis: Patients present with exertional dyspnea and fatigue.

- Severe Pulmonic Stenosis: Patients present with exertional dyspnea, chest pain and syncope.

- Untreated patients develop features of right ventricular failure which include:

- Exercise intolerance

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Swelling of the feet or ankles

- Abdominal discomfort

- Patients with subinfundibular/infundibular PS can be asymptomatic or they may present with angina, dyspnea, dizziness, or syncope.

- Patients with supravalvular PS may be asymptomatic or have symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue on exertion.

| Mild valvular

PS |

Moderate Valvular

PS |

Severe Valvular PS | Infundibular

Pulmonic Stenosis |

Supravalvular

Pulmonic Stenosis |

Right Heart Failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Features |

Asymptomatic |

|

|

|

|

Physical Examination

The common examination findings include:

- Patients with isolated pulmonary stenosis usually appear normal. In patients diagnosed with syndromes associated with pulmonic stenosis syndrome specific physical examination findings are demonstrated.

- Cardiac examination findings are dependent on the degree of the pulmonary stenosis, the pathology of the valve and associated cardiac lesions. The common findings include as follows:

- In mild stenosis findings include normal jugular venous pulse, absent right ventricle lift, ejection click in the pulmonary area which decreases with inspiration, ejection systolic murmur in the pulmonary area heard in the ending of mid systole increasing in intensity during inspiration.[45]

- In severe stenosis findings include:

- Elevated JVP with a prominent "A" wave

- Right ventricular heave

- Louder and longer ejection murmur in the left parasternal area in second and third intercostal space

- Ejection click is softer and absent with increasing severity

- Wide split S2 with reduced or absent P2 component

- Right sided S4 can be audible.

| Mild valvular

PS |

Severe Valvular

PS | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Examination Findings |

|

|

EKG

Patients with mild stenosis usually do not show any EKG changes excepting for right axis deviation of -100° to -110° which is considered normal in children and adults.

In case of severe stenosis the following changes can be noted, which include:[46]

- Features of right ventricular hypertrophy

- Rightward axis deviation

- High R wave amplitude in lead V1

- Deep S waves in the left precordial leads with <1 R:S ratio in lead V6

Echocardiography

Transthoracic 2D Echo and Doppler imaging is the standard diagnostic test to detect and assess the severity of the stenosis.[47]

- Echo shows thickened and dome shaped valves, peak and mean gradients to assess the severity can be measured by Doppler imaging.

- Dysplastic valves are well visualized on echo.[48]

- Always calculate the tricuspid regurgitation gradient to rule out overestimation of the pulmonary stenosis gradient.[49]

- Right ventricular function and ejection fraction is better measured by a 3D echo when compared to a 2D echo.[50]

- Pulmonic Stenosis 1

{{#ev:youtube|4nCLhy6tYBs}}

- Pulmonic Stenosis 2

{{#ev:youtube|s-tfOTR11r0}}

MRI

Cardiac MRI is very useful to study the anatomy of the right ventricular outflow tract, pulmonary artery and to locate the exact level of stenosis.[51]

Cardiac Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization is useful to measure the pressure gradients directly, but its not performed on a regular basis as echo is a reliable and non-invasive test to measure the pressure gradients.[52]

Dual-Source Computed Tomography

It is an accurate imaging technique to evaluate the function and anatomy of the pulmonary valve.[53]

Evaluation of Pulmonary Stenosis in Adolescents and Young Adults

According to 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines[7], following are the guidelines for evaluation of patients with pulmonary stenosis:

| Class I |

| "1. An ECG is recommended for the initial evaluation of pulmonic stenosis in adolescent and young adult patients and serially every 5 to 10 years for follow-up examinations.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "2.Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography is recommended for the initial evaluation of pulmonic stenosis in adolescent and young adult patients, and serially every 5 to 10 years for follow-up examinations.(Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "3.Cardiac catheterization is recommended in the adoles- cent or young adult with pulmonic stenosis for evalu- ation of the valvular gradient if the Doppler peak jet velocity is greater than 3 m per second (estimated peak gradient greater than 36 mm Hg) and balloon dilation can be performed if indicated.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class III |

| "1.Diagnostic cardiac catheterization is not recommended for the initial diagnostic evaluation of pulmonic stenosis in adolescent and young adult patients.(Level of Evidence: C).(Level of Evidence: C) " |

Treatment

Medical Therapy

There is no specific medical therapy for the treatment of pulmonic stenosis. However, patients diagnosed with right heart failure diuretics are recommended to decrease the fluid overload.

Surgery

Indications for surgery

Surgical correction is recommended based on the peak gradient and other associated clinical features:[54]

- Surgery is advised regardless of the symptoms if the Doppler derived peak instantaneous gradient greater than 64 mm Hg (peak velocity >4 m/s).

- In patients with Doppler derived peak instantaneous gradient less than 64 mm Hg (peak velocity >4 m/s), surgery is advised if any of the following is present:

- Symptomatic patient

- Decreased right ventricular function

- Double chambered right ventricle

- Arrhythmias

- Right to left shunting via the VSD or ASD

- Asymptomatic patients with a systolic RV pressure greater than 80 mm Hg (TR velocity >4.3 m/s).

According to 2010, ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease, Indications for intervention in Right Ventricular Outlet Obstruction are as follows:[55]

| Class I |

| "1.RVOTO at any level should be repaired regardless of the symptoms when the doppler peak gradient is >64mm Hg(peak velocity >4.0m/s), provided that the RV function is normal and no valve substitute is required(Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "2.In valvular PS, balloon valvulotomy should be the intervention of choice.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "3.In asymptomatic patients in whom balloon valvulotomy is ineffective and the surgical valve replacement is the only option, surgery should be performed in the presence of a systolic right ventricular pressure greater than 80mm Hg ( TR velocity >4.3m/s)(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIa |

"1.Intervention in patients with gradient <64 mm Hg should be considered in the presence of:

|

"2.Peripheral PS, regardless of the symptoms, should be considered for repair if :

|

Surgical Options

- Balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) has widely replaced surgical valvulotomy as a treatment option for pulmonary valve stenosis.[56][57]

- Catheter intervention is recommended for patients with doming valves which are not dysplastic.[58]

- Surgery is recommended for patients with:

- Subinfundibular or infundibular PS and hypoplastic pulmonary annulus

- Dysplastic pulmonary valves

- Patients with associated lesions which need a surgical approach, such as severe PR or severe TR.

- In patients with significant residual PS after BPV, a redo BPV can be performed with a larger balloon to avoid valve replacement.

- In patients with hemodynamically significant pulmonary regurgitation after valvulotomy or BPV, surgical valve replacement is recommended.

Surgical Outcome

- Surgical outcomes in patients with valvular stenosis is good with survival rate of 90 to 96% 25 years after the surgery when its done in the childhood.[59][60]

- Survival is around 70% at 25 years when the surgery is performed in adulthood.

- BPV has shown to have good outcomes in long term follow up with very low rate of re-intervention requirement.[61][62][63]

- BPV has shown to have sub-optimal results in patients with dysplastic valves when compared to doming valves.[64]

Complications of the surgery

- Post procedural pulmonary regurgitation is a common complication and occurs in 10 to 40% patients. Majority of the patients remain asymptomatic and only few patients develop hemodynamically significant pulmonary regurgitation.[65]

- Bradycardia and hypotension at the time of balloon inflation

- Transient permanent right bundle branch block or atrioventricular block

- Higher mortality rates reported after surgical decompression in patients with RV-dependent coronary circulation.[66]

- Balloon rupture

- Tricuspid papillary muscle rupture

- Perforation of the RV outflow tract

Follow up

Patients with PS are recommended for a regular echocardiography to evaluate the degree of pulmonary regurgitation, RV pressure, RV function and tricuspid regurgitation. The frequency of visits is dependent on the degree of stenosis and is as follows:[7]

- Mild untreated or residual pulmonic stenosis: Follow up once every 5 years.

- Moderate pulmonic stenosis: Annual visit with echocardiography every 2 years.

ACC / AHA Guidelines - Indications for balloon valvotomy in Pulmonary Stenosis (DO NOT EDIT)

According to 2008 ACC/AHA guidelines[7], following are the indications for balloon valvotomy in pulmonary stenosis:

| Class I |

| "1.Balloon valvotomy is recommended in adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonic stenosis who have exertional dyspnea, angina, syncope, or presyncope and an RV–to–pulmonary artery peak-to-peak gradient greater than 30 mm Hg at catheterization.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "2.Balloon valvotomy is recommended in asymptomatic adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonic stenosis and RV–to–pulmonary artery peak-to-peak gradient greater than 40 mm Hg at catheterization.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class III |

| "1.Balloon valvotomy is not recommended in asymptomatic adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonic stenosis and RV–to–pulmonary artery peak-to-peak gradient less than 30 mm Hg at catheterization.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1.Balloon valvotomy may be reasonable in asymptomatic adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonic stenosis and an RV–to–pulmonary artery peak-to-peak gradient 30 to 39 mm Hg at catheterization.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

Recommendations For Pulmonary Valvuloplasty

According to 2011, Indications for Cardiac Catheterization and Intervention in Pediatric Cardiac Disease, A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.[67]

| Class I |

| "1. Pulmonary valvuloplasty is indicated for a patient with critical valvar pulmonary stenosis (defined as pulmonary stenosis present at birth with cyanosis and evidence of patent ductus arteriosus dependency), valvar pulmonic stenosis, and a peak-to-peak catheter gradient or echocardiographic peak instantaneous gradient of >40 mm Hg or clinically significant pulmonary valvar obstruction in the presence of RV dysfunction.(Level of Evidence: A) " |

| Class IIa |

| "1. It is reasonable to perform pulmonary valvuloplasty on a patient with valvar pulmonic stenosis who meets the above criteria in the setting of a dysplastic pulmonary valve.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "2. It is reasonable to perform pulmonary valvuloplasty in newborns with pulmonary valve atresia and intact ventricular septum who have favorable anatomy that includes the exclusion of RV-dependent coronary circulation.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1. Pulmonary valvuloplasty may be considered as a palliative procedure in a patient with complex cyanotic CHD, including some rare cases of tetralogy of Fallot.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class III |

| "1. Pulmonary valvuloplasty should not be performed in patients with pulmonary atresia and RV-dependent coronary circulation.(Level of Evidence: B) " |

Prevention

- There are no specific primary preventive measures.

- Patients with diagnosed pulmonary valvar stenosis are not candidates for infective endocarditis prophylaxis.

- Infective endocarditis prophylaxis is recommended only in patients with prosthetic valves.[68]

Special Situations

Participation In Sports

According to 2005 Task Force 2: Congenital Heart Disease, guidelines for participation in sports are as follows:[69]

Pulmonary valve stenosis in untreated patients

| "1.Athletes with a peak systolic gradient less than 40 mm Hg and normal right ventricular function can participate in all competitive sports if no symptoms are present. Annual re-evaluation is recommended. " |

| "2.Athletes with a peak systolic gradient greater than 40 mm Hg can participate in low-intensity competitive sports (classes IA and IB). Patients in this category usually are referred for balloon valvuloplasty or operative valvotomy before sports participation. " |

Pulmonary valve stenosis treated by operation or balloon valvuloplasty

| "1.Athletes with no or only residual mild PS and normal ventricular function without symptoms can participate in all competitive sports. Participation in sports can begin two to four weeks after balloon valvuloplasty. After operation, an interval of approximately three months is suggested before resuming sports participation. " |

| "2.Athletes with a persistent peak systolic gradient greater than 40 mm Hg should follow the same recommendations as those for patients before treatment." |

| "3.Athletes with severe pulmonary incompetence characterized by a marked right ventricular enlargement can participate in class IA and IB competitive sports." |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJ; et al. (2011). "Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Am Coll Cardiol. 58 (21): 2241–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. PMID 22078432.

- ↑ Paraskevas, G.; Koutsouflianiotis, K.; Iliou, K. (2017). "The first descriptions of various anatomical structures and embryological remnants of the heart: A systematic overview". International Journal of Cardiology. 227: 674–690. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.077. ISSN 0167-5273.

- ↑ Cabrera A, Martinez P, Rumoroso JR, Alcibar J, Arriola J, Pastor E; et al. (1995). "Double-chambered right ventricle". Eur Heart J. 16 (5): 682–6. PMID 7588901.

- ↑ Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, Chambers JB, Evangelista A, Griffin BP; et al. (2009). "Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice". J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 22 (1): 1–23, quiz 101-2. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.029. PMID 19130998.

- ↑ Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM, Thomas JD (2014). "2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63 (22): 2438–88. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.537. PMID 24603192.

- ↑ Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM, Thomas JD (2014). "2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63 (22): 2438–88. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.537. PMID 24603192.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Faxon DP, Freed MD; et al. (2008). "2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". J Am Coll Cardiol. 52 (13): e1–142. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.007. PMID 18848134.

- ↑ Borgdorff MA, Dickinson MG, Berger RM, Bartelds B (2015). "Right ventricular failure due to chronic pressure load: What have we learned in animal models since the NIH working group statement?". Heart Fail Rev. 20 (4): 475–91. doi:10.1007/s10741-015-9479-6. PMC 4463984. PMID 25771982.

- ↑ Pierpont ME, Basson CT, Benson DW, Gelb BD, Giglia TM, Goldmuntz E; et al. (2007). "Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics". Circulation. 115 (23): 3015–38. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. PMID 17519398.

- ↑ Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean L, Bird TD, Fong CT, Mefford HC, Smith R, Stephens K, Allanson JE, Roberts AE. PMID 20301303. Vancouver style error: initials (help); Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Samanta D (2016). "Infantile spasms in Williams-Beuren syndrome with typical deletions of the 7q11.23 critical region and a review of the literature". Acta Neurol Belg. doi:10.1007/s13760-016-0635-0. PMID 27062269.

- ↑ Ghosh SK, Majumdar B, Rudra O, Chakraborty S (2015). "LEOPARD Syndrome". Dermatol Online J. 21 (10). PMID 26632807.

- ↑ Gozali MV, Zhou BR, Luo D (2015). "Generalized lentiginosis in an 11 year old boy". Dermatol Online J. 21 (9). PMID 26437287.

- ↑ Hacıhamdioğlu B, Hacıhamdioğlu D, Delil K (2015). "22q11 deletion syndrome: current perspective". Appl Clin Genet. 8: 123–32. doi:10.2147/TACG.S82105. PMC 4445702. PMID 26056486.

- ↑ Saleh M, Kamath BM, Chitayat D (2016). "Alagille syndrome: clinical perspectives". Appl Clin Genet. 9: 75–82. doi:10.2147/TACG.S86420. PMC 4935120. PMID 27418850.

- ↑ Rodriguez RM, Feinstein JA, Chan FP (2016). "CT-defined phenotype of pulmonary artery stenoses in Alagille syndrome". Pediatr Radiol. 46 (8): 1120–7. doi:10.1007/s00247-016-3580-4. PMID 27041277.

- ↑ Bayramoğlu A, Saritemur M, Tasdemir S, Omeroglu M, Erdem HB, Sahin I (2016). "A rare cause of dyspnea in emergency medicine: Keutel syndrome". Am J Emerg Med. 34 (5): 935.e3–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.020. PMID 26462901.

- ↑ Rowe RD (1973). "Cardiovascular disease in the rubella syndrome". Cardiovasc Clin. 5 (1): 61–80. PMID 4589966.

- ↑ Zampi G, Pergolini A, Celestini A, Benvissuto F, Tinti MD, Ortenzi M; et al. (2016). "[Pulmonary stenosis and atrial septal defect: a rare association in the elderly]". G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 17 (1): 62–3. doi:10.1714/2140.23196. PMID 26901261.

- ↑ Jacobs EG, Leung MP, Karlberg J (2000). "Distribution of symptomatic congenital heart disease in Hong Kong". Pediatr Cardiol. 21 (2): 148–57. doi:10.1007/s002469910025. PMID 10754087.

- ↑ Altrichter PM, Olson LJ, Edwards WD, Puga FJ, Danielson GK (1989). "Surgical pathology of the pulmonary valve: a study of 116 cases spanning 15 years". Mayo Clin Proc. 64 (11): 1352–60. PMID 2593721.

- ↑ Greenberg SB, Crisci KL, Koenig P, Robinson B, Anisman P, Russo P (1997). "Magnetic resonance imaging compared with echocardiography in the evaluation of pulmonary artery abnormalities in children with tetralogy of Fallot following palliative and corrective surgery". Pediatr Radiol. 27 (12): 932–5. doi:10.1007/s002470050275. PMID 9388286.

- ↑ Jashari R, Van Hoeck B, Goffin Y, Vanderkelen A (2009). "The incidence of congenital bicuspid or bileaflet and quadricuspid or quadrileaflet arterial valves in 3,861 donor hearts in the European Homograft Bank". J Heart Valve Dis. 18 (3): 337–44. PMID 19557994.

- ↑ Fernández-Armenta J, Villagómez D, Fernández-Vivancos C, Vázquez R, Pastor L (2009). "Quadricuspid pulmonary valve identified by transthoracic echocardiography". Echocardiography. 26 (3): 288–90. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00798.x. PMID 19017322.

- ↑ Gikonyo BM, Lucas RV, Edwards JE (1987). "Anatomic features of congenital pulmonary valvar stenosis". Pediatr Cardiol. 8 (2): 109–16. doi:10.1007/BF02079465. PMID 2957652.

- ↑ Snellen HA, Hartman H, Buis-Liem TN, Kole EH, Rohmer J (1968). "Pulmonic stenosis". Circulation. 38 (1 Suppl): 93–101. PMID 4889601.

- ↑ Jonas SN, Kligerman SJ, Burke AP, Frazier AA, White CS (2016). "Pulmonary Valve Anatomy and Abnormalities: A Pictorial Essay of Radiography, Computed Tomography (CT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)". J Thorac Imaging. 31 (1): W4–12. doi:10.1097/RTI.0000000000000182. PMID 26656195.

- ↑ Koretzky ED, Moller JH, Korns ME, Schwartz CJ, Edwards JE (1969). "Congenital pulmonary stenosis resulting from dysplasia of valve". Circulation. 40 (1): 43–53. PMID 5792996.

- ↑ Koretzky ED, Moller JH, Korns ME, Schwartz CJ, Edwards JE (1969). "Congenital pulmonary stenosis resulting from dysplasia of valve". Circulation. 40 (1): 43–53. PMID 5792996.

- ↑ Waller BF (1984). "Morphological aspects of valvular heart disease: Part II". Curr Probl Cardiol. 9 (8): 1–74. PMID 6391843.

- ↑ Simula DV, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Connolly HM, Schaff HV (2002). "Surgical pathology of carcinoid heart disease: a study of 139 valves from 75 patients spanning 20 years". Mayo Clin Proc. 77 (2): 139–47. doi:10.4065/77.2.139. PMID 11838647.

- ↑ Paredes A, Valdebenito M, Gabrielli L, Castro P, Zalaquett R (2014). "[Tricuspid and pulmonary valve involvement in carcinoid syndrome. Report of two cases]". Rev Med Chil. 142 (5): 662–6. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872014000500017. PMID 25427026.

- ↑ Gabriele OF, Scatliff JH (1970). "Pulmonary valve calcification". Am Heart J. 80 (3): 299–302. PMID 5448727.

- ↑ Vela JE, Contreras R, Sosa FR (1969). "Rheumatic pulmonary valve disease". Am J Cardiol. 23 (1): 12–8. PMID 5380838.

- ↑ Raanani E, Yau TM, David TE, Dellgren G, Sonnenberg BD, Omran A (2000). "Risk factors for late pulmonary homograft stenosis after the Ross procedure". Ann Thorac Surg. 70 (6): 1953–7. PMID 11156101.

- ↑ Vakilian F, Shabestari MM, Poorzand H, Teshnizi MA, Allahyari A, Memar B (2016). "Primary Pulmonary Valve Leiomyosarcoma in a 35-Year-Old Woman". Tex Heart Inst J. 43 (1): 84–7. doi:10.14503/THIJ-14-4748. PMC 4810595. PMID 27047294.

- ↑ van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJ; et al. (2011). "Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Am Coll Cardiol. 58 (21): 2241–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. PMID 22078432.

- ↑ Naderi S (1979). "Congenital abnormalities in newborns of consanguineous and nonconsanguineous parents". Obstet Gynecol. 53 (2): 195–9. PMID 570260.

- ↑ Hayes CJ, Gersony WM, Driscoll DJ, Keane JF, Kidd L, O'Fallon WM; et al. (1993). "Second natural history study of congenital heart defects. Results of treatment of patients with pulmonary valvar stenosis". Circulation. 87 (2 Suppl): I28–37. PMID 8425320.

- ↑ Mody MR (1975). "The natural history of uncomplicated valvular pulmonic stenosis". Am Heart J. 90 (3): 317–21. PMID 1163423.

- ↑ Wolfe RR, Driscoll DJ, Gersony WM, Hayes CJ, Keane JF, Kidd L; et al. (1993). "Arrhythmias in patients with valvar aortic stenosis, valvar pulmonary stenosis, and ventricular septal defect. Results of 24-hour ECG monitoring". Circulation. 87 (2 Suppl): I89–101. PMID 8425327.

- ↑ Kim DH, Park SJ, Jung JW, Kim NK, Choi JY (2013). "The Comparison between the Echocardiographic Data to the Cardiac Catheterization Data on the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Follow-Up in Patients Diagnosed as Pulmonary Valve Stenosis". J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 21 (1): 18–22. doi:10.4250/jcu.2013.21.1.18. PMC 3611114. PMID 23560138.

- ↑ Hornberger LK, Barrea C (2001). "Diagnosis, natural history, and outcome of fetal heart disease". Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 4: 229–43. PMID 11460987.

- ↑ Capuruço CA, Vercosa NC, Lopes RM (2016). "EP08.08: Critical pulmonary valve stenosis in dichorionic and diamniotic twins: prenatal diagnosis, pregnancy outcomes and postnatal development". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 48 Suppl 1: 297–8. doi:10.1002/uog.16888. PMID 27646419.

- ↑ Hultgren HN, Reeve R, Cohn K, McLeod R (1969). "The ejection click of valvular pulmonic stenosis". Circulation. 40 (5): 631–40. PMID 5377205.

- ↑ Cuypers JA, Witsenburg M, van der Linde D, Roos-Hesselink JW (2013). "Pulmonary stenosis: update on diagnosis and therapeutic options". Heart. 99 (5): 339–47. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301964. PMID 23303481.

- ↑ Weyman AE, Hurwitz RA, Girod DA, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H, Green D (1977). "Cross-sectional echocardiographic visualization of the stenotic pulmonary valve". Circulation. 56 (5): 769–74. PMID 912836.

- ↑ Musewe NN, Robertson MA, Benson LN, Smallhorn JF, Burrows PE, Freedom RM; et al. (1987). "The dysplastic pulmonary valve: echocardiographic features and results of balloon dilatation". Br Heart J. 57 (4): 364–70. PMC 1277176. PMID 2953383.

- ↑ Silvilairat S, Cabalka AK, Cetta F, Hagler DJ, O'Leary PW (2005). "Echocardiographic assessment of isolated pulmonary valve stenosis: which outpatient Doppler gradient has the most clinical validity?". J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 18 (11): 1137–42. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2005.03.041. PMID 16275521.

- ↑ Ahmed MI, Escañuela MG, Crosland WA, McMahon WS, Alli OO, Nanda NC (2014). "Utility of live/real time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in the assessment and percutaneous intervention of bioprosthetic pulmonary valve stenosis". Echocardiography. 31 (4): 531–3. doi:10.1111/echo.12551. PMID 24646027.

- ↑ Rajiah P, Nazarian J, Vogelius E, Gilkeson RC (2014). "CT and MRI of pulmonary valvular abnormalities". Clin Radiol. 69 (6): 630–8. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2014.01.019. PMID 24582177.

- ↑ Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA; et al. (2008). "ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease)". Circulation. 118 (23): 2395–451. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190811. PMID 18997168.

- ↑ Sun Z, Xu W, Huang S, Chen Y, Guo X, Shi Z (2016). "Dual-Source Computed Tomography Evaluation of Children with Congenital Pulmonary Valve Stenosis". Iran J Radiol. 13 (2): e34399. doi:10.5812/iranjradiol.34399. PMC 5037969. PMID 27703660.

- ↑ Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA; et al. (2008). "ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease)". Circulation. 118 (23): e714–833. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190690. PMID 18997169.

- ↑ Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, de Haan F, Deanfield JE, Galie N; et al. (2010). "ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010)". Eur Heart J. 31 (23): 2915–57. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249. PMID 20801927.

- ↑ Peterson C, Schilthuis JJ, Dodge-Khatami A, Hitchcock JF, Meijboom EJ, Bennink GB (2003). "Comparative long-term results of surgery versus balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonary valve stenosis in infants and children". Ann Thorac Surg. 76 (4): 1078–82, discussion 1082-3. PMID 14529989.

- ↑ Rao PS (2007). "Percutaneous balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty: state of the art". Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 69 (5): 747–63. doi:10.1002/ccd.20982. PMID 17330270.

- ↑ Jarrar M, Betbout F, Farhat MB, Maatouk F, Gamra H, Addad F; et al. (1999). "Long-term invasive and noninvasive results of percutaneous balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty in children, adolescents, and adults". Am Heart J. 138 (5 Pt 1): 950–4. PMID 10539828.

- ↑ Earing MG, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Ammash NM, Grogan M, Warnes CA (2005). "Long-term follow-up of patients after surgical treatment for isolated pulmonary valve stenosis". Mayo Clin Proc. 80 (7): 871–6. doi:10.4065/80.7.871. PMID 16007892.

- ↑ Idrizi S, Milev I, Zafirovska P, Tosheski G, Zimbakov Z, Ampova-Sokolov V; et al. (2015). "Interventional Treatment of Pulmonary Valve Stenosis: A Single Center Experience". Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 3 (3): 408–12. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.089. PMC 4877828. PMID 27275259.

- ↑ Rao PS, Galal O, Patnana M, Buck SH, Wilson AD (1998). "Results of three to 10 year follow up of balloon dilatation of the pulmonary valve". Heart. 80 (6): 591–5. PMC 1728864. PMID 10065029.

- ↑ Ananthakrishna A, Balasubramonium VR, Thazhath HK, Saktheeshwaran M, Selvaraj R, Satheesh S; et al. (2014). "Balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty in adults: immediate and long-term outcomes". J Heart Valve Dis. 23 (4): 511–5. PMID 25803978.

- ↑ Masura J, Burch M, Deanfield JE, Sullivan ID (1993). "Five-year follow-up after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty". J Am Coll Cardiol. 21 (1): 132–6. PMID 8417053.

- ↑ Sehar T, Qureshi AU, Kazmi U, Mehmood A, Hyder SN, Sadiq M (2015). "Balloon valvuloplasty in dysplastic pulmonary valve stenosis: immediate and intermediate outcomes". J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 25 (1): 16–21. doi:01.2015/JCPSP.1621 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 25604363. - ↑ Masura J, Burch M, Deanfield JE, Sullivan ID (1993). "Five-year follow-up after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty". J Am Coll Cardiol. 21 (1): 132–6. PMID 8417053.

- ↑ Giglia TM, Mandell VS, Connor AR, Mayer JE, Lock JE (1992). "Diagnosis and management of right ventricle-dependent coronary circulation in pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum". Circulation. 86 (5): 1516–28. PMID 1423965.

- ↑ Feltes TF, Bacha E, Beekman RH, Cheatham JP, Feinstein JA, Gomes AS; et al. (2011). "Indications for cardiac catheterization and intervention in pediatric cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 123 (22): 2607–52. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821b1f10. PMID 21536996.

- ↑ Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Faxon DP, Freed MD; et al. (2008). "2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Circulation. 118 (15): e523–661. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190748. PMID 18820172.

- ↑ "Participants/authors". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 45 (8): 1313–1315. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.004. ISSN 0735-1097.