ST elevation myocardial infarction electrocardiogram: Difference between revisions

Rim Halaby (talk | contribs) |

Rim Halaby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

| '''Leads''' || '''Interpretation'''|| '''Involved artery''' | | '''Leads''' || '''Interpretation'''|| '''Involved artery''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| V1-V2-V3 || Anterior [[ischemia]]<ref name="pmid11994554">{{cite journal| author=Gibson CM, Chen M, Angeja BG, Murphy SA, Marble SJ, Barron HV et al.| title=Precordial ST-segment depression in inferior myocardial infarction is associated with slow flow in the non-culprit left anterior descending artery. | journal=J Thromb Thrombolysis | year= 2002 | volume= 13 | issue= 1 | pages= 9-12 | pmid=11994554 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11994554 }} </ref>, or <br> [[Posterior MI]] <ref name="pmid20723851">{{cite journal| author=Pride YB, Tung P, Mohanavelu S, Zorkun C, Wiviott SD, Antman EM et al.| title=Angiographic and clinical outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes presenting with isolated anterior ST-segment depression: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38) substudy. | journal=JACC Cardiovasc Interv | year= 2010 | volume= 3 | issue= 8 | pages= 806-11 | pmid=20723851 | doi=10.1016/j.jcin.2010.05.012 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20723851 }} </ref>, or <br> Reciprocal changes<ref name="pmid2522957">{{cite journal| author=Norell MS, Lyons JP, Gardener JE, Layton CA, Balcon R| title=Significance of "reciprocal" ST segment depression: left ventriculographic observations during left anterior descending coronary angioplasty. | journal=J Am Coll Cardiol | year= 1989 | volume= 13 | issue= 6 | pages= 1270-4 | pmid=2522957 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=2522957 }} </ref>|| [[LAD]] <br> [[RCA]] or [[left circumflex artery]] <br> | | V1-V2-V3 || Anterior [[ischemia]]<ref name="pmid11994554">{{cite journal| author=Gibson CM, Chen M, Angeja BG, Murphy SA, Marble SJ, Barron HV et al.| title=Precordial ST-segment depression in inferior myocardial infarction is associated with slow flow in the non-culprit left anterior descending artery. | journal=J Thromb Thrombolysis | year= 2002 | volume= 13 | issue= 1 | pages= 9-12 | pmid=11994554 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11994554 }} </ref>, or <br> [[Posterior MI]] <ref name="pmid20723851">{{cite journal| author=Pride YB, Tung P, Mohanavelu S, Zorkun C, Wiviott SD, Antman EM et al.| title=Angiographic and clinical outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes presenting with isolated anterior ST-segment depression: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38) substudy. | journal=JACC Cardiovasc Interv | year= 2010 | volume= 3 | issue= 8 | pages= 806-11 | pmid=20723851 | doi=10.1016/j.jcin.2010.05.012 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20723851 }} </ref>, or <br> Reciprocal changes<ref name="pmid2522957">{{cite journal| author=Norell MS, Lyons JP, Gardener JE, Layton CA, Balcon R| title=Significance of "reciprocal" ST segment depression: left ventriculographic observations during left anterior descending coronary angioplasty. | journal=J Am Coll Cardiol | year= 1989 | volume= 13 | issue= 6 | pages= 1270-4 | pmid=2522957 | doi= | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=2522957 }} </ref>|| [[LAD]] <br> [[RCA]] or [[left circumflex artery]] <br>- | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 21:10, 17 March 2014

|

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction Microchapters |

|

Differentiating ST elevation myocardial infarction from other Diseases |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

|

Case Studies |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction electrocardiogram On the Web |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction electrocardiogram in the news |

|

Blogs on ST elevation myocardial infarction electrocardiogram |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating ST elevation myocardial infarction |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for ST elevation myocardial infarction electrocardiogram |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

A primary purpose of the electrocardiogram is to detect ischemia or acute coronary injury in broad, symptomatic emergency department populations. Common EKG findings in STEMI include ST segment elevation, new LBBB pattern and hyperacute T waves.

Electrocardiogram

The 12 lead ECG is used to classify patients into one of three groups:

- Those with ST segment elevation or new bundle branch block (suspicious for acute injury and a possible candidate for acute reperfusion therapy with thrombolytics or primary PCI),

- Those with ST segment depression or T wave inversion (suspicious for ischemia), and

- Those with a so-called non-diagnostic or normal ECG.[1]

A normal ECG does not rule out the presence of acute myocardial infarction. Sometimes the earliest presentation of acute myocardial infarction is instead the presence of a hyperacute T wave.[2] In clinical practice, hyperacute T waves are rarely seen, because they exists for only 2-30 minutes after the onset of infarction.[3] Hyperacute T waves need to be distinguished from the peaked T waves associated with hyperkalemia.[4]

ST Elevation

The electrocardiographic definition of ST elevation MI requires the following: at least 1 mm (0.1 mV) of ST segment elevation in 2 or more anatomically contiguous leads.[1] While these criteria are sensitive, they are not specific as thrombotic coronary occlusion is not the most common cause of ST segment elevation in chest pain patients.[5]

ST Depression

ST depression in the anterior leads might either represent reciprocal changes on EKG[6] or might be pathologically caused by either anterior ischemia in the context of a patent artery[7] or posterior infarct due to the complete occlusion of a coronary artery.[8]

Shown below is a table depicting the interpretation of ST elevation and ST depression by the involved contiguous leads.

| ST elevation | ||

| Leads | Interpretation | Involved artery |

| V1-V2 | Septal MI, or Right ventricular MI[9] |

LAD RCA |

| V3-V4 | Anterior MI | LAD |

| V5-V6 I-aVL |

Lateral MI | Left circumflex artery |

| II-III-aVF | Inferior MI | RCA in 85% of the cases Left circumflex artery in 15% of the cases |

| V1-V2- V4R | Right ventricular MI[10] | RCA |

| ST depression | ||

| Leads | Interpretation | Involved artery |

| V1-V2-V3 | Anterior ischemia[7], or Posterior MI [8], or Reciprocal changes[6] |

LAD RCA or left circumflex artery - |

EKG Examples

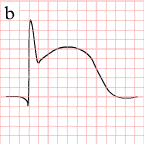

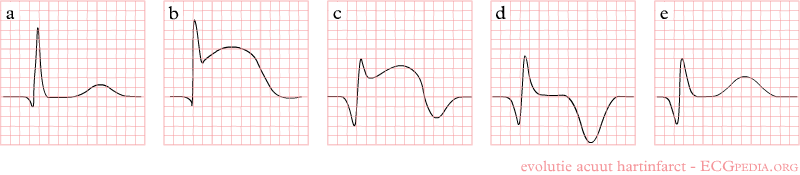

Shown below is an EKG of STEMI demonstrating the evolution of an infarct on the EKG. ST elevation, Q wave formation, T wave inversion, normalization with a persistent Q wave.

Copyleft image obtained courtesy of ECGpedia, http://en.ecgpedia.org/wiki/File:AMI_evolutie.png

Shown below is an EKG demonstrating ST elevation in lead V1 and aVr; reversal of V6 depicting STEMI.

Copyleft image obtained courtesy of ECGpedia,http://en.ecgpedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

Shown below is an EKG demonstrating ST elevation in the right precordial leads depicting STEMI

Copyleft image obtained courtesy of, http://en.ecgpedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

Shown below is an EKG demonstrating clear ST elevation in the right precordial leads depicting STEMI. A coronary angiography revealed a proximal right coronary artery occlusion.

Copyleft image obtained courtesy of, http://en.ecgpedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

For more EKG examples of ST elevation myocardial infarction click here

Limitations of the 12 lead ECG

While clinicians are widely familar with the 12 lead ECG, there are limitations to its sensitivity and specificity in detecting myocardial injury due to thrombotic vessel occlusion. A single static ECG represents a brief sample in time. In STEMI, the culprit artery is often opening and closing or "winking and blinking" due to cyclic flow variations with the clot dissolving and reforming again. Furthermore, patients with acute coronary syndromes often have rapidly changing supply versus demand characteristics. As a clinical example, one of the authors (CM Gibson) once saw a patient with 6 hours of chest pain who had non-specific ECG changes. 15 minutes later the patient complained of worsening chest pain, and at that time the ECG showed ST elevation. Had the second ECG with ST elevation been instead the first ECG that was reviewed, it would have been concluded that the patient was infarcting for over 6 hours, when instead, the artery was occluded for 15 minutes at most during the recent episode of chest pain. Because a single ECG may not accurately represent evolving myocardial injury, it is standard practice to obtain serial 12 lead ECGs, particularly if the first ECG is obtained during a pain-free episode. Alternatively, many emergency departments and chest pain centers use computers capable of continuous ST segment monitoring.[11] While the standard 12 lead ECG is well designed to detect anterior ischemia, by virtue of the fact that it samples only electrical vectors from the front left chest wall, the 12 lead ECG may miss right ventricular and posterior infarctions. In particular, acute myocardial infarction in the distribution of the circumflex artery is likely to produce a nondiagnostic ECG or ST segment depression in the anterior precordial leads. The use of non-standard ECG leads like right-sided lead V4R and posterior leads V7, V8, and V9 may improve sensitivity for right ventricular and posterior myocardial infarction. Newer technologies such as the 80 lead ECG have demonstrated greater sensitivity in detecting RV and posterior infarcts compared with the 12 lead ECG. The failure to identify patients with ST elevation MI delays care and has a negative effect on the quality of patient care.[12]

Localization of the Culprit Artery Based Upon the 12 lead ECG

While the ECG leads that are involved with ST elevation and depression are often used to predict the potential location of the culprit artery, the sensitivity and specificity of these techniques are often poor. New technologies such as 80 lead ECGs may prove to be more useful in this regard. Identification of the potential culprit artery can be important in guiding patient management. In particular, the ECG should be used to identify patients with a right ventricular infarct where nitrate administration is contraindicated. The 12 lead ECG can also be used to identify the most appropriate artery to perform angiography on first when performing primary angioplasty.

| Wall Affected | Leads Showing ST Segment Elevation | Leads Showing Reciprocal ST Segment Depression | Suspected Culprit Artery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septal | V1, V2 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterior | V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anteroseptal | V1, V2, V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterolateral | V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left Anterior Descending (LAD), Circumflex (LCX), or Obtuse Marginal |

| Extensive anterior (Sometimes called Anteroseptal with Lateral extension) | V1,V2,V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left main coronary artery (LCA) |

| Inferior | II, III, aVF | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) or Circumflex (LCX) |

| Lateral | I, aVL, V5, V6 | II, III, aVF | Circumflex (LCX) or Obtuse Marginal |

| Posterior (Usually associated with Inferior or Lateral but can be isolated) | V7, V8, V9 | V1,V2,V3, V4 | Posterior Descending (PDA) (branch of the RCA or Circumflex (LCX)) |

| Right ventricular (Usually associated with Inferior) | II, III, aVF, V1, V4R | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) |

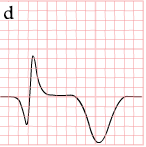

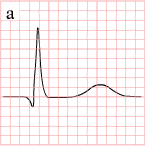

Evolution of ST Segment Elevation

As the myocardial infarction evolves, there may be loss of R wave height and development of pathological Q waves. T wave inversion may persist for months or even permanently following acute myocardial infarction.[13] Typically, however, the T wave recovers, leaving a pathological Q wave as the only remaining evidence that an acute myocardial infarction has occurred. Understanding the typical time course of ST changes in acute MI is critical in distinguishing STEMI from pericarditis and other conditions.

| Figure | change | |

|---|---|---|

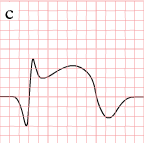

| minutes |

|

hyperacute T waves (peaked T waves)

ST-elevation |

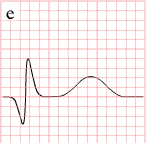

| hours |

|

ST-elevation, with terminal negative T wave

negative T wave (these can last for months) |

| days |

|

Pathologic Q Waves |

Measurement of the Magnitude of ST Elevation: 60 Milliseconds after the J point

The optimal time after the J point to measure ST elevation is debated. This example shows the technique of measuring the magnitude of ST elevation 60 milliseconds or 1.5 small boxes after the J point.

Distinguishing Early Repolarization and Other Normal Variants from Pathologic ST Elevation

Early repolarization is an electrocardiographic pattern that can mimic the changes of ST elevation myocardial infarction. It is often seen in younger males. As the example below shows, there is often a notch (shown in red) where the QRS and ST segments join.

Copyleft image obtained courtesy of ECGpedia, http://en.ecgpedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

Diagnosing STEMI in the Setting of Left Bundle Branch Block

Ordinarily in the setting of left bundle branch block, the T waves are inverted in the lateral leads (they are 'discordant'). If they become upright, they are called 'concordant', and concordant T waves can be observed in ST elevation MI. The EKG below was obtained in a patient with a new left bundle branch block (LBBB) and a totally occluded left anterior descending artery.

2013 Revised and 2004 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (DO NOT EDIT)[14]

Electrocardiogram (DO NOT EDIT)[14][15]

| Class I |

| "1. Performance of a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) by emergency medical services personnel at the site of first medical contact (FMC) is recommended in patients with symptoms consistent with STEMI[16][17][18][19][20] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| "2. A 12-lead ECG should be performed and shown to an experienced emergency physician within 10 minutes of ED arrival on all patients with chest discomfort (or anginal equivalent) or other symptoms suggestive of STEMI.(Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "3. If the initial ECG is not diagnostic of STEMI but the patient remains symptomatic, and there is a high clinical suspicion for STEMI, serial ECGs at 5- to 10- minute intervals or continuous 12-lead ST-segment monitoring should be performed to detect the potential development of ST elevation.(Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "4. In patients with inferior STEMI, right-sided ECG leads should be obtained to screen for ST elevation suggestive of RV infarction.(Level of Evidence: B)" |

Sources

- 2013 Revised ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction[14]

- The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction [15]

Related Chapters

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care - Part 8: Stabilization of the Patient With Acute Coronary Syndromes." Circulation 2005; 112: IV-89 - IV-110.

- ↑ Somers MP, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A (2002). "The prominant T wave: electrocardiographic differential diagnosis". Am J Emerg Med. 20 (3): 243–51. PMID 11992348. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Smith SW, Whitwam W. "Acute Coronary Syndromes." Emerg Med Clin N Am 2006; 24(1): 53-89. PMID 16308113

- ↑ "The clinical value of the ECG in noncardiac conditions." Chest 2004; 125(4): 1561-76. PMID 15078775

- ↑ Smith SW, Whitwam W (2006). "Acute coronary syndromes". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 24 (1): 53–89, vi. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2005.08.008. PMID 16308113. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Norell MS, Lyons JP, Gardener JE, Layton CA, Balcon R (1989). "Significance of "reciprocal" ST segment depression: left ventriculographic observations during left anterior descending coronary angioplasty". J Am Coll Cardiol. 13 (6): 1270–4. PMID 2522957.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gibson CM, Chen M, Angeja BG, Murphy SA, Marble SJ, Barron HV; et al. (2002). "Precordial ST-segment depression in inferior myocardial infarction is associated with slow flow in the non-culprit left anterior descending artery". J Thromb Thrombolysis. 13 (1): 9–12. PMID 11994554.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pride YB, Tung P, Mohanavelu S, Zorkun C, Wiviott SD, Antman EM; et al. (2010). "Angiographic and clinical outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes presenting with isolated anterior ST-segment depression: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38) substudy". JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 3 (8): 806–11. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2010.05.012. PMID 20723851.

- ↑ Tsuka Y, Sugiura T, Hatada K, Nakamura S, Yuasa F, Iwasaka T (2001). "Clinical significance of ST-segment elevation in lead V1 in patients with acute inferior wall Q-wave myocardial infarction". Am Heart J. 141 (4): 615–20. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.113996. PMID 11275929.

- ↑ Klein HO, Tordjman T, Ninio R, Sareli P, Oren V, Lang R; et al. (1983). "The early recognition of right ventricular infarction: diagnostic accuracy of the electrocardiographic V4R lead". Circulation. 67 (3): 558–65. PMID 6821897.

- ↑ Selker HP, Zalenski RJ, Antman EM; et al. (1997). "An evaluation of technologies for identifying acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department: executive summary of a National Heart Attack Alert Program Working Group Report". Ann Emerg Med. 29 (1): 1–12. PMID 8998085. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Masoudi FA, Magid DJ, Vinson DR; et al. (2006). "Implications of the failure to identify high-risk electrocardiogram findings for the quality of care of patients with acute myocardial infarction: results of the Emergency Department Quality in Myocardial Infarction (EDQMI) study". Circulation. 114 (15): 1565–71. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623652. PMID 17015790. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Namba Y, Bando M, Takeda K, Iwata M, Mannen T (1991). "[Marchiafava-Bignami disease with symptoms of the motor impersistence and unilateral hemispatial neglect]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku (in Japanese). 31 (6): 632–5. PMID 1934778. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD; et al. (2012). "2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84. PMID 23247303. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC, Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK (2004). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction)". Circulation. 110 (9): e82–292. PMID 15339869. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Le May MR, So DY, Dionne R; et al. (2008). "A citywide protocol for primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (3): 231–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073102. PMID 18199862. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Dieker HJ, Liem SS, El Aidi H; et al. (2010). "Pre-hospital triage for primary angioplasty: direct referral to the intervention center versus interhospital transport". JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 3 (7): 705–11. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2010.04.010. PMID 20650431. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Diercks DB, Kontos MC, Chen AY; et al. (2009). "Utilization and impact of pre-hospital electrocardiograms for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: data from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53 (2): 161–6. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.030. PMID 19130984. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rokos IC, French WJ, Koenig WJ; et al. (2009). "Integration of pre-hospital electrocardiograms and ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks: impact on Door-to-Balloon times across 10 independent regions". JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2 (4): 339–46. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2008.11.013. PMID 19463447. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Sørensen JT, Terkelsen CJ, Nørgaard BL; et al. (2011). "Urban and rural implementation of pre-hospital diagnosis and direct referral for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction". Eur. Heart J. 32 (4): 430–6. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq437. PMID 21138933. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Unrecognized language

- Disease

- Cardiology

- Ischemic heart diseases

- Intensive care medicine

- Emergency medicine

- Primary care

- Up-To-Date

- Up-To-Date cardiology

- Mature chapter