Leopard syndrome: Difference between revisions

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

Zeisler and Becker first described a syndrome with multiple [[lentigo|lentigines]], [[hypertelorism]], [[pectus carinatum]] (protruding breastbone) and [[prognathism]] (protrusion of lower jaw) in 1936.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Zeisler EP, Becker SW|title=Generalized lentigo: its relation to systemic nonelevated nevi|journal=Arch Dermatol Syphilol|year=1936|volume=33|pages=109–125}}</ref> Sporadic descriptions were added through the years. In 1962, cardiac abnormalities and short stature were first associated with the condition.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Moynahan EJ|title=Multiple symmetrical moles, with psychic and somatic infantilism and genital hypoplasia: first male case of a new syndrome|journal=Proc Roy Soc Med|volume= 55|pages=959–960|year=1962 }} {{PMC|1896920}} <!--not indexed on Pubmed--></ref> In 1966, three familial cases were added, a mother, her son and daughter.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Walther RJ, Polansky BJ, Grotis IA |title=Electrocardiographic abnormalities in a family with generalized lentigo |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=275 |issue=22 |pages=1220–5 |year=1966 |pmid=5921856 |doi=}}</ref> Another case of mother to two separate children, with different paternity of the two children, was added in 1968.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Matthews NL |title=Lentigo and electrocardiographic changes |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=278 |issue=14 |pages=780–1 |year=1968 |pmid=5638719 |doi=}}</ref> | Zeisler and Becker first described a syndrome with multiple [[lentigo|lentigines]], [[hypertelorism]], [[pectus carinatum]] (protruding breastbone) and [[prognathism]] (protrusion of lower jaw) in 1936.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Zeisler EP, Becker SW|title=Generalized lentigo: its relation to systemic nonelevated nevi|journal=Arch Dermatol Syphilol|year=1936|volume=33|pages=109–125}}</ref> Sporadic descriptions were added through the years. In 1962, cardiac abnormalities and short stature were first associated with the condition.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Moynahan EJ|title=Multiple symmetrical moles, with psychic and somatic infantilism and genital hypoplasia: first male case of a new syndrome|journal=Proc Roy Soc Med|volume= 55|pages=959–960|year=1962 }} {{PMC|1896920}} <!--not indexed on Pubmed--></ref> In 1966, three familial cases were added, a mother, her son and daughter.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Walther RJ, Polansky BJ, Grotis IA |title=Electrocardiographic abnormalities in a family with generalized lentigo |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=275 |issue=22 |pages=1220–5 |year=1966 |pmid=5921856 |doi=}}</ref> Another case of mother to two separate children, with different paternity of the two children, was added in 1968.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Matthews NL |title=Lentigo and electrocardiographic changes |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=278 |issue=14 |pages=780–1 |year=1968 |pmid=5638719 |doi=}}</ref> | ||

It was believed as late as 2002<ref>[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2006/MB_cgi?mode=&term=LEOPARD+Syndrome&field=entry National Library of Medicine MeSH: C05.660.207.525]</ref> that Leopard syndrome was related to [[neurofibromatosis type I]] (von Recklinghausen syndrome). In fact, since both [[ICD9]] and [[ICD10]] lack a specific diagnosis code for LEOPARD syndrome, the diagnosis code for [[Neurofibromatosis type I|NF1]] is still sometimes used for diagnostic purposes, although it has been shown that the gene is not linked to the [[Neurofibromatosis type I|NF1]] locus.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ahlbom BE, Dahl N, Zetterqvist P, Annerén G |title=Noonan syndrome with café-au-lait spots and multiple lentigines syndrome are not linked to the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus |journal=Clin. Genet. |volume=48 |issue=2 |pages=85–9 |year=1995 |pmid=7586657 |doi=}}</ref> | It was believed as late as 2002<ref>[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2006/MB_cgi?mode=&term=LEOPARD+Syndrome&field=entry National Library of Medicine MeSH: C05.660.207.525]</ref> that Leopard syndrome was related to [[neurofibromatosis type I]] (von Recklinghausen syndrome). In fact, since both [[ICD9]] and [[ICD10]] lack a specific diagnosis code for LEOPARD syndrome, the diagnosis code for [[Neurofibromatosis type I|NF1]] is still sometimes used for diagnostic purposes, although it has been shown that the gene is not linked to the [[Neurofibromatosis type I|NF1]] locus.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ahlbom BE, Dahl N, Zetterqvist P, Annerén G |title=Noonan syndrome with café-au-lait spots and multiple lentigines syndrome are not linked to the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus |journal=Clin. Genet. |volume=48 |issue=2 |pages=85–9 |year=1995 |pmid=7586657 |doi=}}</ref> | ||

==Pathophysiology== | ==Pathophysiology== | ||

Revision as of 17:41, 4 September 2013

| LEOPARD syndrome | ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

| 21 month old, third generation patient, confirmed by genetic tests as Y279C, exhibiting ocular hyperteliorism, cephalofacial similarity. | ||

| OMIM | 151100 | |

| DiseasesDB | 7387 | |

| eMedicine | derm/627 | |

| MeSH | C05.660.207.525 | |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Leopard syndrome |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Leopard syndrome Most cited articles on Leopard syndrome |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Leopard syndrome |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Leopard syndrome at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Leopard syndrome Clinical Trials on Leopard syndrome at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Leopard syndrome NICE Guidance on Leopard syndrome

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Leopard syndrome Discussion groups on Leopard syndrome Patient Handouts on Leopard syndrome Directions to Hospitals Treating Leopard syndrome Risk calculators and risk factors for Leopard syndrome

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Leopard syndrome |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohamed Moubarak, M.D. [2]

Overview

Leopard syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant,[1] multisystem disease caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11 gene (PTPN11). The disease is a complex of features, mostly involving the skin, skeletal and cardiovascular systems, they may or may not be present in all patients. The nature of how the mutation causes each of the condition's symptoms is not well known, however research is ongoing. Related to Noonan syndrome, Leopard syndrome is caused by a different missense mutation of the same gene. Leopard syndrome may also be called multiple lentigines syndrome, cardiomyopathic lentiginosis, Gorlin's syndrome II, Capute-Rimoin-Konigsmark-Esterly-Richardson syndrome, or Moynahan syndrome. Noonan syndrome is fairly common (1:1000 to 1:2500 live births), and neurofibromatosis 1 (which was once thought to be related to LEOPARD syndrome) is also common (1:3500), but however no epidemiologic data exists for Leopard syndrome.[2]

Historical Perspective

Zeisler and Becker first described a syndrome with multiple lentigines, hypertelorism, pectus carinatum (protruding breastbone) and prognathism (protrusion of lower jaw) in 1936.[3] Sporadic descriptions were added through the years. In 1962, cardiac abnormalities and short stature were first associated with the condition.[4] In 1966, three familial cases were added, a mother, her son and daughter.[5] Another case of mother to two separate children, with different paternity of the two children, was added in 1968.[6] It was believed as late as 2002[7] that Leopard syndrome was related to neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen syndrome). In fact, since both ICD9 and ICD10 lack a specific diagnosis code for LEOPARD syndrome, the diagnosis code for NF1 is still sometimes used for diagnostic purposes, although it has been shown that the gene is not linked to the NF1 locus.[8]

Pathophysiology

In the two predominant mutations of Leopard syndrome, the mutations cause a loss of catalytic activity of the SHP2 protein(the gene product of the PTPN11 gene), which is a previously unrecognized behavior for this class of mutations.[9] This interferes with growth factor and related signalling. While further research confirms this mechanism,[10][11] additional research is needed to determine how this relates to all of the observed effects of Leopard syndrome.

Differentiating Leopard Syndrome from other Diseases

Epidemiology and Demographics

Various literature describes it as being "rare"[12] or "extremely rare".[13] There is no epidemiologic data available regarding how many in the world population suffer from the syndrome, however there are slightly over 100 cases described in medical literature.

Natural History, Complication and Prognosis

In itself, Leopard syndrome is not a life threatening diagnosis, most people diagnosed with the condition live normal lives. Obstructive cardiomyopathy and other pathologic findings involving the cardiovascular system may be a cause of death in those whose cardiac deformities are profound. It is suggested that, once diagnosed, individuals be routinely followed by a cardiologist, endocrinologist, dermatologist, and other appropriate specialties as symptoms present.

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

The name of the condition is a mnemonic, originally coined in 1969,[14] as the condition is characterized by some of the following seven conditions, the first letters of which spell LEOPARD, along with the characteristic "freckling" of the skin, caused by the lentigines that is reminiscent of the large cat

- Lentigines - Reddish-brown to dark brown macules (surface skin lesion) generally occurring in a high number (10,000+) over a large portion of the skin, at times higher than 80% coverage. These can even appear inside the mouth (Buccal mucosa), or on the surface of the eye (scleral). These have irregular borders and range in size from 1 mm in diameter to café-au-lait spot's, several cm's in diameter. Also, some areas of vitiligo-like hypopigmentation may be observed

- Electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities: Generally observed on an electrocardiograph as a bundle branch block

- Ocular hypertelorism- Wideset eyes, which lead to a similar facial resemblance between patients. Facial abnormalities are the second highest occurring symptom after the lentigines. Abnormalities also include: broad nasal root, prognathism (protruding lower jaw), or low-set, possibly rotated ears

- Pulmonary stenosis - Narrowing of the pulmonary artery as it exits the heart. Other cardiac abnormalities may be present, including aortic stenosis, or mitral valve prolapse

- Abnormal genitalia - Usually cryptorchidism (retention of testicles in body) or monorchism (single testicle). In female patients, this presents as missing or single ovaries, much harder by nature to detect. Ultrasound imaging is performed at regular intervals, from the age of 1 year, to determine if ovaries are present

- Retarded growth - Slow, or stunted growth. Most newborns with this syndrome are of normal birth weight and length, but will often slow within the first year

- Sensorineural deafness

The presence of all of these hallmarks is not needed for a diagnosis. A clinical diagnosis is considered made when, with lentigines present there are 2 other symptoms observed, such as ECG abnormalities and ocular hypertelorism, or without lentigines, 3 of the above conditions are present, with a first-degree relative (i.e. parent, child, sibling) with a clinical diagnosis.[15]

- additional dermatologic abnormalities (axillary freckling, localized hypopigmentation, interdigital webbing, hyperelastic skin)

- Mild mental retardation is observed in about 30% of those affected with the syndrome

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movements), seizures, or hyposmia (reduced ability to smell) has been documented in a few patients

- In 2004, a patient was reported with recurrent upper extremity aneurysms that required surgical repairs.[16]

- In 2006, a LEOPARD syndrome patient was reported with acute myelogenous leukemia.[17]

Unfortunately, due to the rarity of the syndrome itself, it is hard to determine whether certain additional diseases are actually a threat of the syndrome. With a base population of possibly less than one thousand individuals, one or two outlying cases can skew the statistical population very quickly.

-

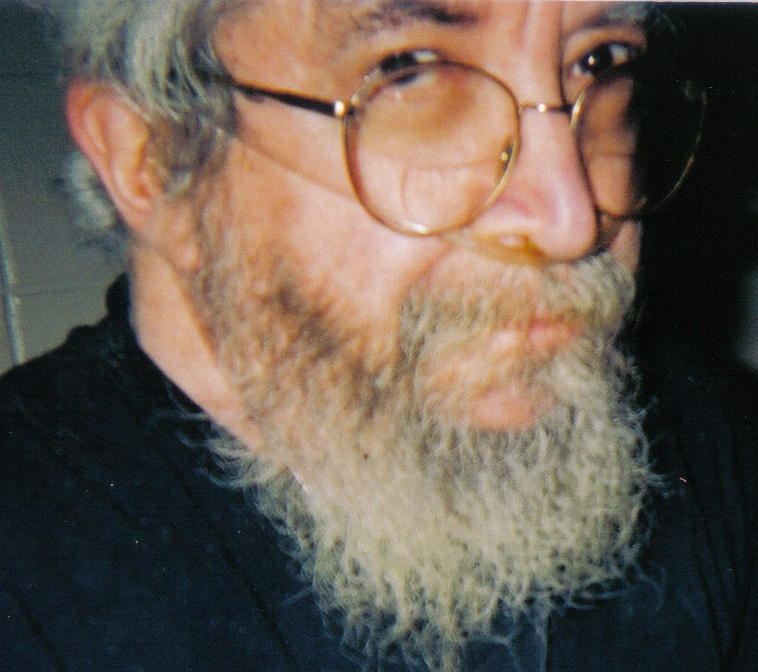

Three-quarter facial view, first generation patient showing slight prognathism and low set ears.

-

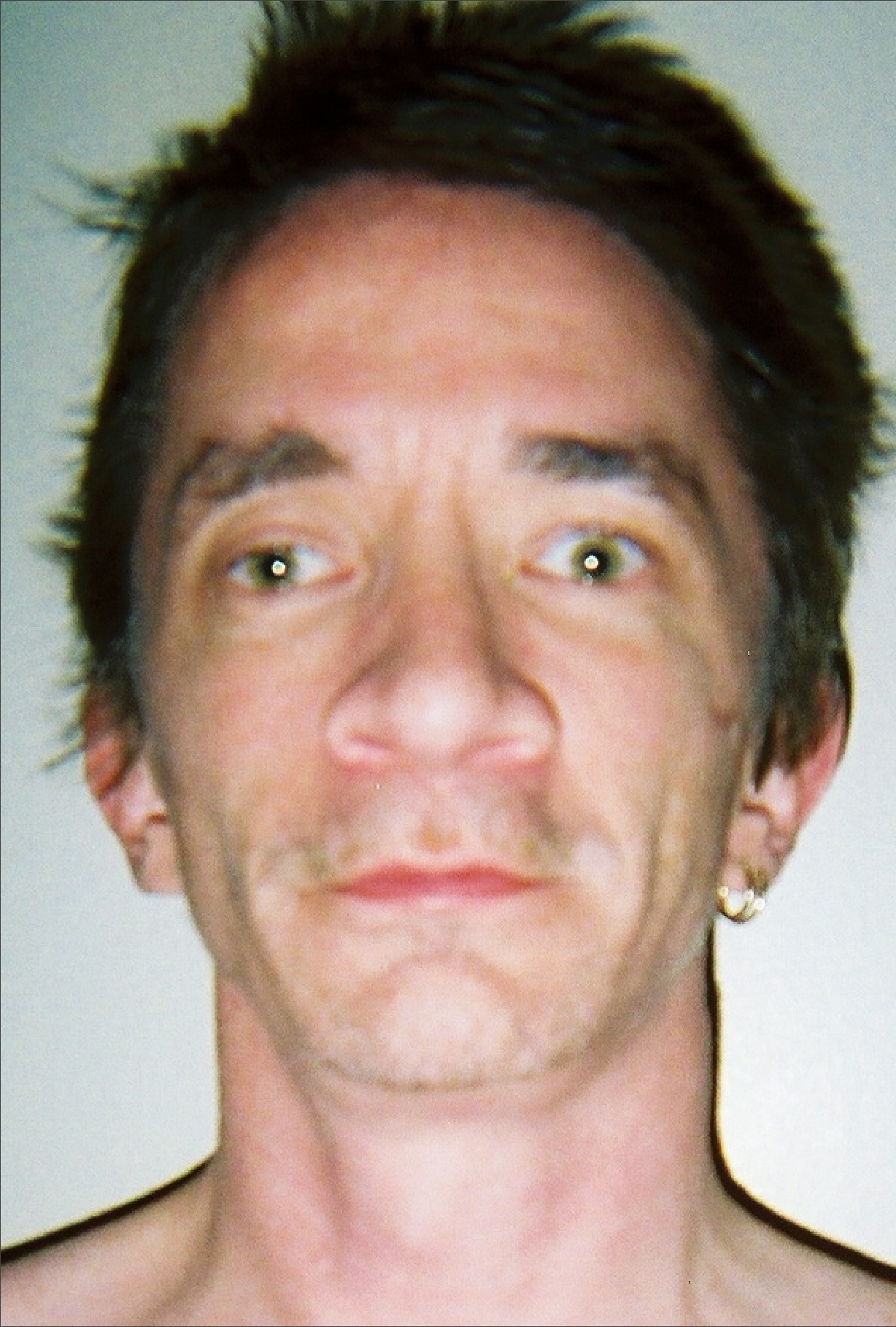

Thirty seven year old, second generation patient, exhibiting hypertelorism, broad nasal root, slight ptosis

-

Hand of thirty seven year old patient showing interdigital webbing

-

Thirty seven year old patient demonstrating hyperelasticity

-

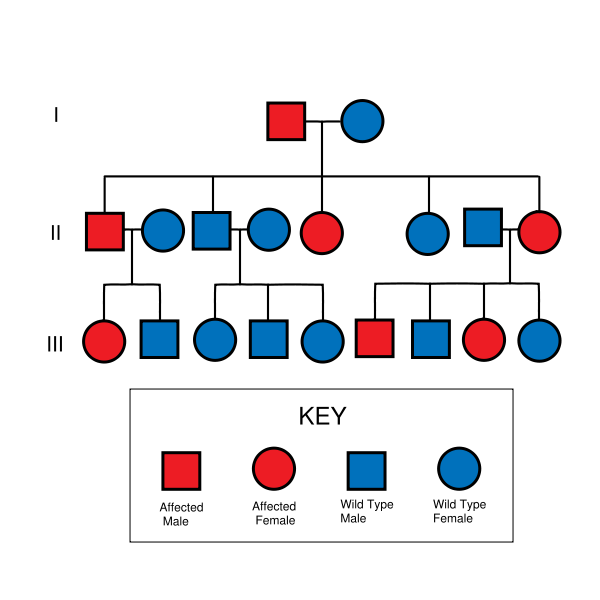

LEOPARD syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, although it can also arise due to spontaneous mutation.

-

21 month old, third generation patient, confirmed by genetic tests as Y279C, exhibiting ocular hyperteliorism, cephalofacial similarity.

-

Torso of thirty seven year old, second generation patient, exhibiting lentiginosis.

Laboratory Findings

The presence of the disease can be confirmed with a genetic test. In a study of 10 infants with clinical indications of Leopard syndrome prior to their first birthday, 8 (80%) patients were confirmed to have the suspected mutation. An additional patient, with the suspected mutation was subsequently found to have NF1, following evaluation of the mother.[18] There are 5 identified allelic variants responsible for Leopard syndrome. which seems to be a unique familial mutation, in that all other variants are caused by transition errors, rather than transversion.

Imaging Studies

- CT scanning or MRI - Brain atrophy may be revealed

- Skeletal radiography - Detection of skeletal malformation and bone age assessment.

- Echocardiography - Indicated for visualization of structural heart abnormalities.

- Electrocardiography - Excludes conduction abnormalities.

- Ultrasonography or Urographic examination - For assessment of the genitourinary system.

- Audiography or Auditory evoked potentials - For detection of sensorineural deafness.

Treatment

It is recommended that those with the syndrome who are capable of having children seek genetic counseling before deciding to have children. As the syndrome presents frequently as a forme fruste (incomplete, or unusual form) variant, an examination of all family members must be undertaken.[12] As an autosomal dominant trait there is a fifty percent chance with each child, that they will also be born with the syndrome. This does not take into account the possibility of the gene mutating on its own, in a child of a LEOPARD syndrome patient who does not inherit the gene from the affected parent. Since the syndrome has a variable penetrance and expression, one generation may have a mild expression of the syndrome, while the next may be profoundly affected.

Once a decision to have children is made and the couple conceives, the fetus is monitored during the pregnancy for cardiac evaluation. If a gross cardiac malformation is found, parents receive counseling on continuing with the pregnancy.

Other management is routine care as symptoms present:[12]

- For those with endocrine issues (low levels of thyrotopin [a pituitary hormone responsible for regulating thyroid hormones], follicle stimulating hormone) drug therapy is recommended.

- For those who are disturbed by the appearance of lentigines, cryosurgery may be beneficial. Due to the large number of lentigines this may prove time consuming. Retinoids Decrease abnormal hyperproliferative keratinocytes and may reduce potential for malignant degeneration, So an alternative treatment with tretinoin or hydroquinone creams may help. Hydroquinone Lightens hyperpigmented skin Through inhibiting enzymatic oxidation of tyrosine and suppressing other melanocyte metabolic processes which will inhibite melanogenesis.

- Drug therapies for those with cardiac abnormalities, as those abnormalities become severe enough to warrant the use of these therapies. ECG's are mandatory prior to any surgical interventions, due to possible arrythmia.

See also

References

- ↑ Coppin BD, Temple IK (1997). "Multiple lentigines syndrome (LEOPARD syndrome or progressive cardiomyopathic lentiginosis)". J. Med. Genet. 34 (7): 582–6. PMID 9222968.

- ↑ Tullu MS, Muranjan MN, Kantharia VC; et al. (2000). "Neurofibromatosis-Noonan syndrome or LEOPARD Syndrome? A clinical dilemma". J Postgrad Med. 46 (2): 98–100. PMID 11013475.

- ↑ Zeisler EP, Becker SW (1936). "Generalized lentigo: its relation to systemic nonelevated nevi". Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 33: 109–125.

- ↑ Moynahan EJ (1962). "Multiple symmetrical moles, with psychic and somatic infantilism and genital hypoplasia: first male case of a new syndrome". Proc Roy Soc Med. 55: 959–960. PMC 1896920

- ↑ Walther RJ, Polansky BJ, Grotis IA (1966). "Electrocardiographic abnormalities in a family with generalized lentigo". N. Engl. J. Med. 275 (22): 1220–5. PMID 5921856.

- ↑ Matthews NL (1968). "Lentigo and electrocardiographic changes". N. Engl. J. Med. 278 (14): 780–1. PMID 5638719.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine MeSH: C05.660.207.525

- ↑ Ahlbom BE, Dahl N, Zetterqvist P, Annerén G (1995). "Noonan syndrome with café-au-lait spots and multiple lentigines syndrome are not linked to the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus". Clin. Genet. 48 (2): 85–9. PMID 7586657.

- ↑ Tartaglia M, Martinelli S, Stella L; et al. (2006). "Diversity and functional consequences of germline and somatic PTPN11 mutations in human disease". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78 (2): 279–90. doi:10.1086/499925. PMID 16358218.

- ↑ Hanna N, Montagner A, Lee WH; et al. (2006). "Reduced phosphatase activity of SHP-2 in LEOPARD syndrome: consequences for PI3K binding on Gab1". FEBS Lett. 580 (10): 2477–82. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.088. PMID 16638574.

- ↑ Kontaridis MI, Swanson KD, David FS, Barford D, Neel BG (2006). "PTPN11 (Shp2) mutations in LEOPARD syndrome have dominant negative, not activating, effects". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (10): 6785–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M513068200. PMID 16377799.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sergiusz Jozwiak, MD, PhD. "eMedicine - LEOPARD Syndrome". Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ↑ "NORD - National Organization for Rare Disorders, Inc". Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ↑ Gorlin RJ, Anderson RC, Blaw M (1969). "Multiple lentigenes syndrome". Am. J. Dis. Child. 117 (6): 652–62. PMID 5771505.

- ↑ Voron DA, Hatfield HH, Kalkhoff RK (1976). "Multiple lentigines syndrome. Case report and review of the literature". Am. J. Med. 60 (3): 447–56. PMID 1258892.

- ↑ Yagubyan M, Panneton JM, Lindor NM, Conti E, Sarkozy A, Pizzuti A (2004). "LEOPARD syndrome: a new polyaneurysm association and an update on the molecular genetics of the disease". J. Vasc. Surg. 39 (4): 897–900. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2003.11.030. PMID 15071461. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Uçar C, Calýskan U, Martini S, Heinritz W (2006). "Acute myelomonocytic leukemia in a boy with LEOPARD syndrome (PTPN11 gene mutation positive)". J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 28 (3): 123–5. doi:10.1097/01.mph.0000199590.21797.0b. PMID 16679933. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Digilio MC, Sarkozy A, de Zorzi A; et al. (2006). "LEOPARD syndrome: clinical diagnosis in the first year of life". Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 140 (7): 740–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31156. PMID 16523510.