Tricuspid atresia pathophysiology

|

Tricuspid atresia Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Special Scenarios |

|

Case Studies |

|

Tricuspid atresia pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Tricuspid atresia pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Tricuspid atresia pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Sara Zand, M.D.[2] Keri Shafer, M.D. [3] Priyamvada Singh, MBBS [4]; Assistant Editor-In-Chief: Kristin Feeney, B.S. [5]

Overview

Tricuspid atresia was first discovered by Friedrich Ludwig kreysig in 1817, a German physician who found the obstruction between the right atrium and right ventricle in the autopsy of cyanotic infants. The classic term of tricuspid atresia was used firstly by schuberg in 1861

Historical perspective

- Tricuspid atresia was first discovered by Friedrich Ludwig kreysig in 1817, a German physician who found the obstruction between the right atrium and right ventricle in the autopsy of cyanotic infants.

- The classic term of tricuspid atresia was used firstly by schuberg in 1861.

Overview

Tricuspid atresia occurs during prenatal development. In tricuspid atresia, there is no continuity between the right atrium and right ventricle. Inferior vena cava and superior vena cava collect venous nonoxygenated blood into the right atrium. Through atrial septal defect (ASD), blood come into the left atrium, then left ventricle andaorta.This blood is a mixture of saturated and unsaturated O2. If there is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), this mixed blood in the left ventricle flows into the right ventricle, then via pulmonary artery reaches pulmonary bed and becomes oxygenated, then returns back into the left atrium viapulmonary veins. In diminished pulmonary blood flow whether the flow is dependent on patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), the mixed-blood in aorta flows from this passage intopulmonary artery and pulmonary bed. In the presence of normal positioning of great arteries, cyanosis is more prominent and is affected by the size of VSD. Transpositioning great arteries (TGA) and subaortic stenosis are other associated anomalies.

Pathophysiology

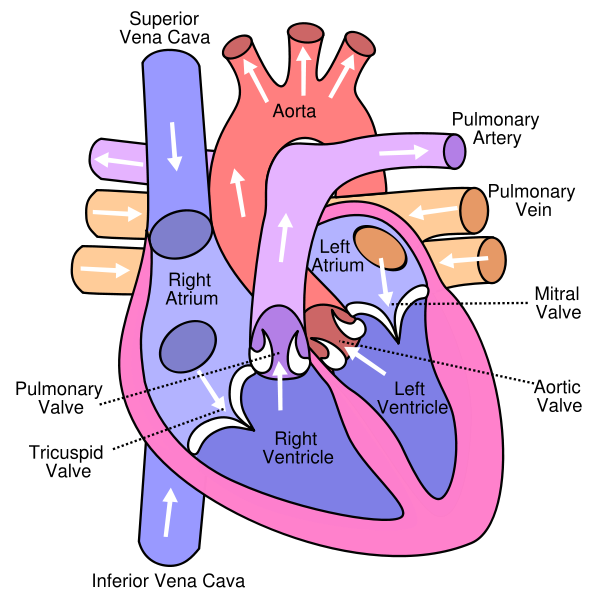

Normal Human Heart

Tricuspid Atresia

{{#ev:youtube|BsvdUEbHyDE}}

- Tricuspid atresia occurs during prenatal development.

- In tricuspid atresia, there is no continuity between the right atrium and right ventricle.

- Inferior vena cava and superior vena cava collect venous nonoxygenated blood into the right atrium.

- Through atrial septal defect (ASD), blood come into the left atrium, then left ventricle andaorta.

- This blood is a mixture of saturated and unsaturated O2.

- If there is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), this mixed blood in the left ventricle flows into the right ventricle, then via pulmonary artery reaches pulmonary bed and becomes oxygenated, then returns back into the left atrium viapulmonary veins.

- In diminished pulmonary blood flow whether the flow is dependent on patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), the mixed-blood in aorta flows from this passage intopulmonary artery and pulmonary bed.

- In the presence of normal positioning of great arteries, cyanosis is more prominent and is affected by the size of VSD.

- Transpositioning great arteries (TGA) and subaortic stenosis are other associated anomalies.

Classification

Tricuspid atresia is classified according to the connection between ventricles with greatarteries (aorta, pulmonary) into two subgroups:[1]

- Normal connection between ventricles with the aorta and pulmonary artery which is the common type and is consistent with 70%-80% of cases. Most patients are cyanotic.[2]

- Aorta originated from small right ventricle and the pulmonary artery comes from the left ventricle. Heart failure and pulmonary hypertension are common and patients are not cyanotic. Flow in the aorta is dependent on ventricular setrum defect(VSD) size. Subaortic stenosis and aortic arch anomalies are common.

References

- ↑ ASTLEY R, OLDHAM JS, PARSONS C (July 1953). "Congenital tricuspid atresia". Br Heart J. 15 (3): 287–97. doi:10.1136/hrt.15.3.287. PMC 479498. PMID 13059216.

- ↑ Rao PS (January 2009). "Diagnosis and management of cyanotic congenital heart disease: part I". Indian J Pediatr. 76 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1007/s12098-009-0030-4. PMID 19391004.