Tolosa-Hunt syndrome

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Jyostna Chouturi, M.B.B.S [2] Rithish Nimmagadda,MBBS.[3]

| Tolosa–Hunt syndrome | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

|---|---|

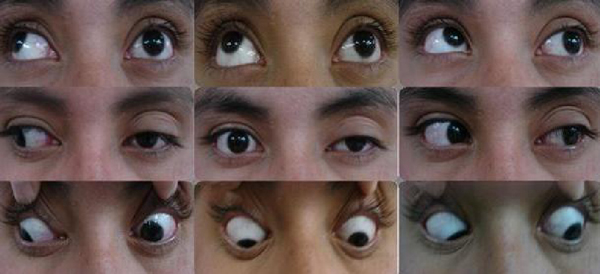

| Neuro-ophthalmologic examination showing ophthalmoplegia in a patient with Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, prior to treatment. The central image represents forward gaze, and each image around it represents gaze in that direction (for example, in the upper left image, the patient looks up and right; the left eye is unable to accomplish this movement). The examination shows ptosis of the left eyelid, exotropia (outward deviation) of the primary gaze of the left eye, and paresis (weakness) of the left third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves. |

Overview

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome (THS) is a rare disorder characterized by severe and unilateral headaches with extraocular palsies, usually involving the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth cranial nerves, and pain around the sides and back of the eye, along with weakness and paralysis (ophthalmoplegia) of certain eye muscles.[1]

In 2004, the International Headache Society provided a definition of the diagnostic criteria which included granuloma.[2]

Causes

The exact cause of THS is not known, but the disorder is thought to be, and often assumed to be, associated with inflammation of the areas behind the eyes (cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure).On histopathology, there is a nonspecific inflammation of the septa and wall of the cavernous sinus, with a lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration, giant cell granulomas, and proliferation of fibroblasts.Pressure and subsequent dysfunction of the cavernous sinus components, such as cranial nerves III, IV, and VI and the superior divisions of cranial nerve V, are caused by the inflammation.Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

In addition, affected individuals may experience paralysis of various facial nerves and drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis). Other signs include double vision, fever, chronic fatigue, vertigo or arthralgia. Occasionally the patient may present with a feeling of protrusion of one or botheyeballs (exophthalmos).[3][4]

Diagnosis

THS is usually diagnosed via exclusion, and as such a vast amount of laboratory tests are required to rule out other causes of the patient's symptoms.[3] These tests include a complete blood count, thyroid function tests and serum protein electrophoresis.[3] Studies of cerebrospinal fluid may also be beneficial in distinguishing between THS and conditions with similar signs and symptoms.[3]

MRI scans of the brain and orbit with and without contrast, magnetic resonance angiography or digital subtraction angiography and a CT scan of the brain and orbit with and without contrast may all be useful in detecting inflammatory changes in the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure and/or orbital apex.[3] Inflammatory change of the orbit on cross sectional imaging in the absence of cranial nerve palsy is described by the more benign and general nomenclature of orbital pseudotumor.

Sometimes a biopsy may need to be obtained to confirm the diagnosis, as it is useful in ruling out a neoplasm.[3]

Blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing should be part of the examination process if the MRI is normal or exhibits alterations that are consistent with cavernous sinus inflammation. This will help rule out other potential causes of orbital or cranial base inflammation. Among the suggested blood tests are:

Complete blood count; electrolytes; glucose and hemoglobin A1C; tests for kidney and liver function; angiotensin converting enzyme; antinuclear antibody; anti-double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (anti-dsDNA) antibody; anti-Sm antibody; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; fluorescent treponemal antibody test; lymphome serologies; serum protein electrophoresis; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and C reactive protein These results are often normal in people with Tolosa-Hunt syndrome [12]. While Tolosa-Hunt syndrome has been linked to case reports of high ESR, moderate leukocytosis, and antinuclear antibody concentrations, these anomalies should indicate an underlying connective tissue condition.

Here is a summary of the precise diagnostic standards that the International Headache Society has recommended:

A single-sided headache, as well as granulomatous inflammation of the orbit, superior orbital fissure, or cavernous sinus, as seen by an MRI or biopsy, Paresis of one or more of the ipsilateral fourth, fifth, or sixth cranial nerves, as well as proof of both of the following in support of the cause: •Headache either began concurrently with or ≤2 weeks before oculomotor paresis. •Ipsilateral to the granulomatous inflammation is the headache. Symptoms that a different diagnosis cannot adequately explain The diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome can be made with a high degree of sensitivity (95 to 100 percent) using these combined clinical and radiologic criteria.

Differentials to consider when diagnosing THS include craniopharyngioma, migraine and meningioma.[3]

Treatment

Treatment of THS is usually completed using corticosteroids (often prednisolone) and immunosuppressive agents (such as methotrexate or azathioprine).[3] Corticosteroids act as analgesia and reduce pain (usually within 24–72 hours), as well as reducing the inflammatory mass, whereas immunosuppressive agents help reduce the autoimmune response.[3] Treatment is then continued in the same dosages for a further 7–10 days and then tapered slowly.[3]

A suggested glucocorticoid regimen is:

Prednisone 80 to 100 mg daily for three days. If the pain has resolved, taper to 60 mg daily, then 40 mg, then 20 mg, then 10 mg every two weeks.

Radiotherapy has also been proposed.[5]

Prognosis

The prognosis of THS is usually considered good. Patients usually respond to corticosteroids, and spontaneous remission can occur, although movement of ocular muscles may remain damaged.[3] Roughly 30–40% of patients who are treated for THS experience a relapse.[3]

Epidemiology

THS is uncommon in both the United States and internationally. In New Zealand, there is only one recorded case .[3] Both genders, male and female, are affected equally, and it typically occurs around the age of 60.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Tolosa–Hunt syndrome". Who Named It. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ La Mantia L, Curone M, Rapoport AM, Bussone G (2006). "Tolosa–Hunt syndrome: critical literature review based on IHS 2004 criteria". Cephalalgia. 26 (7): 772–81. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01115.x. PMID 16776691.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedeMedicine - ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednord - ↑ Foubert-Samier A, Sibon I, Maire JP, Tison F (2005). "Long-term cure of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome after low-dose focal radiotherapy". Headache. 45 (4): 389–91. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05077_5.x. PMID 15836581.