Hemolytic anemia

| Hemolytic anemia | |

| |

|---|---|

| Bone Marrow: Leukoerythroblastic Reaction and Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia in a Patient with Bone Marrow Metastasis Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-10 | D55-D59 |

| ICD-9 | 282, 283, 773 |

| DiseasesDB | 5534 |

| MedlinePlus | 000571 |

|

Hemolytic anemia Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Hemolytic anemia On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Hemolytic anemia |

For patient information on this, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Synonyms and keywords: Haemolytic anaemia

Overview

Hemolytic anemia is anemia due to hemolysis, the abnormal breakdown of red blood cells either in the blood vessels (intravascular hemolysis) or elsewhere in the body (extravascular). It has numerous possible causes, ranging from relatively harmless to life-threatening. The general classification of hemolytic anemia is either acquired or inherited. Treatment depends on the cause and nature of the breakdown.

In a healthy person, a red blood cell survives 90 to 120 days (on average) in the circulation, so about 1% of human red blood cells break down each day. The spleen (part of the reticulo-endothelial system) is the main organ which removes old and damaged RBCs from the circulation. In health the break down and removal of RBCs from the circulation is matched by the production of new RBCs in the bone marrow.

When the rate of breakdown increases, the body compensates by producing more RBCs, but if compensation is inadequate clinical problems can appear. Breakdown of RBCs can exceed the rate that the body can make RBCs and so anemia can develop. The breakdown products of hemoglobin will accumulate in the blood causing jaundice and be excreted in the urine causing the urine to become dark brown in colour.

Symptoms

Signs of anemia are generally present (fatigue, later heart failure). Jaundice may be present.

- certain aspects of the medical history can suggest a cause for hemolysis (drugs, fava bean or other sensitivity, prosthetic heart valve, or another medical illness)

Clinical findings in haemolytic anaemias:

- increased serum bilirubin levels in blood, therefore jaundice

- pallor in mucous membrane and skin

- increased urobilinogen in urine. urine turns dark on standing

- Splenomegaly

- Pigmented gallstones may be found

Tests

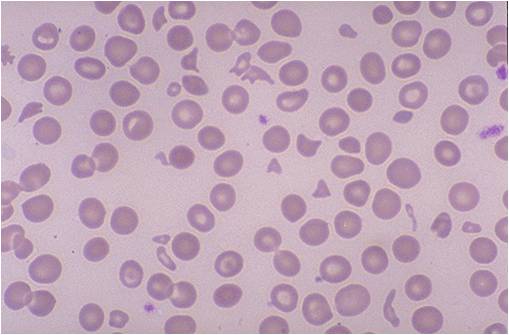

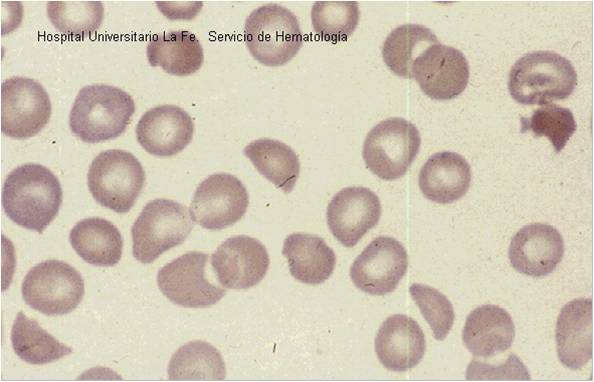

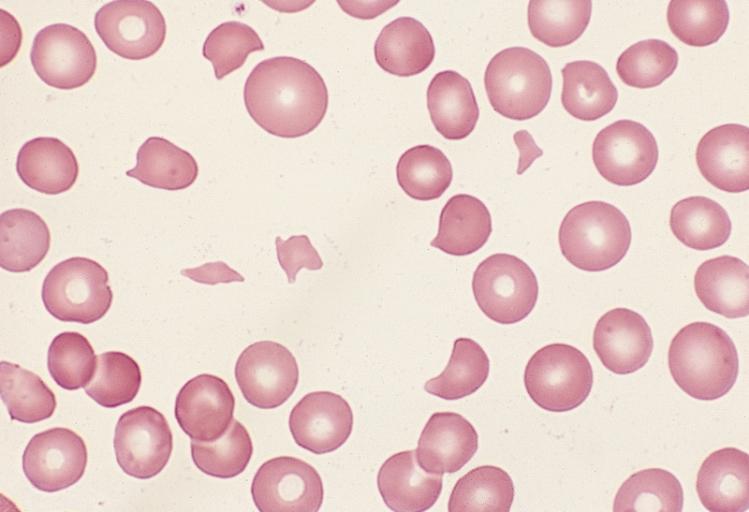

- Peripheral blood smear microscopy:

- fragments of the red blood cells ("schistocytes") can be present

- some red blood cells may appear smaller and rounder than usual (spherocytes)

- reticulocytes are present in elevated numbers. This may be overlooked if a special stain is not used.

- The level of Unconjugated bilirubin in the blood is elevated. This may lead to jaundice.

- The level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the blood is elevated

- Haptoglobin levels are decreased

- The direct Coombs test is positive, if hemolysis is caused by an immune process.

- Haemosiderin in the urine indicates chronic intravascular haemolysis. There is also urobilinogen in the urine.

(Images shown below are courtesy of Melih Aktan MD, Istanbul Medical Faculty - Turkey, and Hospital Universitario La Fe Servicio Hematologia)

Classification of hemolytic anaemias

Causes of haemolytic anaemis can be either genetic or acquired.

Genetic

- Genetic conditions of RBC membrane

- Genetic conditions of RBC metabolism (enzyme defects)

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD or favism)

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Genetic conditions of haemoglobin

Acquired

Acquired haemolytic anaemia can be further divided into immune and non-immune mediated.

Immune mediated hemolytic anaemia (direct Coombs test is positive)

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Idiopathic

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Evans' syndrome (antiplatelet antibodies and haemolytic antibodies)

- Cold antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Idiopathic cold hemagglutinin syndrome

- Infectious mononucleosis and mycoplasma ( atypical) pneumonia

- Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (rare)

- Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Alloimmune hemolytic anemia

- Haemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)

- Rh disease (Rh D)

- ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Anti-Kell hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Rhesus c hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Rhesus E hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Other blood group incompatibility (RhC, Rhe, Kidd, Duffy, MN, P and others)

- Alloimmune hemolytic blood transfusion reactions (ie from a non-compatible blood type)

- Haemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)

- Drug induced immune mediated hemolytic anaemia

- Penicillin (high dose)

- Methyldopa

Non-immune mediated haemolytic anaemia (direct Coombs test is negative)

- Drugs (i.e., some drugs and other ingested substances lead to haemolysis by direct action on RBCs)

- Toxins (e.g., snake venom)

- Trauma

- Mechanical (heart valves, extensive vascular surgery, microvascular disease)

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (a specific subtype with causes such as TTP, HUS, DIC and HELLP syndrome)

- Infections

- Membrane disorders

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (rare acquired clonal disorder of red blood cell surface proteins)

- Liver disease

Drug induced hemolysis

Drug induced hemolysis has large clinical relevance. It occurs when drugs actively provoke red cell destruction. Four mechanisms are described below.

Immune

Penicillin in high doses can induce immune mediated hemolysis via the hapten mechanism in which antibodies are targeted against the combination of penicillin in association with red blood cells. Complement is activated by the attached antibody leading to the removal of red blood cells by the spleen.

The drug itself can be targeted by the immune system, e.g. by IgE in a Type I hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin, rarely leading to anaphylaxis.

Non-immune

Non-immune drug induced hemolysis can occur via oxidative mechanisms. This is particularly likely to occur when there is an enzyme deficiency in the antioxidant defence system of the red blood cells. An example is where antimalarial oxidant drugs like primaquine damage red blood cells in Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in which the red blood cells are more susceptible to oxidative stress due to reduced NADPH production consequent to the enzyme deficiency.

Some drugs cause RBC (red blood cell) lysis even in normal individuals. These include dapsone and sulfasalazine.

Non-immune drug-induced hemolysis can also arise from drug-induced damage to cell volume control mechanisms; for example drugs can directly or indirectly impair regulatory volume decrease mechanisms, which become activated during hypotonic RBC swelling to return the cell to a normal volume. The consequence of the drugs actions are irreversible cell swelling and lysis (e.g. ouabain at very high doses).

Differential diagnosis

- Ineffective hematopoiesis is sometimes misdiagnosed as hemolysis.

- Clinically these conditions may share many features of hemolysis

- Red cell breakdown occurs before a fully developed red cell is released into the circulation.

- Examples: thalassemia, myelodysplastic syndrome

- Megaloblastic anemia due to deficiency in vitamin B12 or folic acid.

Therapy

Definitive therapy depends on the cause.

- Symptomatic treatment can be given by blood transfusion, if there is marked anaemia.

- In severe immune-related hemolytic anemia, steroid therapy is sometimes necessary.

- Sometimes splenectomy can be helpful where extravascular heamolysis is predominant (ie most of the red blood cells are being removed by the

spleen).

ar:فقر الدم التحللي de:Hämolytische Anämie sr:Хемолитичка анемија