Giant cell tumor of bone overview

|

Giant cell tumor of bone Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Giant cell tumor of bone from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Giant cell tumor of bone overview On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Giant cell tumor of bone overview |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Giant cell tumor of bone overview |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Giant cell tumor of the bone is a relatively uncommon tumor. It is characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells (osteoclast-like cells). These tumors are generally benign. In most patients, the tumors are slow to develop, but may recur locally in as many as 50% of cases. Metastasis to the lungs may occur.

Giant cell tumor of the bone is an aggressive skeletal lesion typically located in the epiphyseal end of a long bone.

Epidemiology

The tumor predominantly occurs in the third and fourth decade of life with a slight predilection for females. It is more common in females with the rate of growth enhanced in pregnancy

Pathophysiology

GCT is characterized by the presence of numerous Cathepsin-K producing, CD33 +, CD14 - multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells and plump spindle-shaped stromal cells that represent the main proliferating cell population. The spindle-shaped mononuclear cells are believed to represent the neoplastic population and are characterized at the cytogenetic level by telomeric associations and a peculiar telomere-protecting capping mechanism. Areas of regressive change such as necrosis or fibrosis as well as extensive hemorrhage are frequently present. It recurs from time to time and rates between 25–50% have been reported[2, 6, 15]. In very rare cases, a malignant change may occur.

Prevalence

Giant cell tumor of the bone accounts for 4-5% of primary bone tumors and 18.2% of benign bone tumors[1]. Giant cell tumors are mostly benign, however 5-10% of patients may have a malignant tumor.

20% of all benign bone tumours and 5% of all tumours are giant cell tumours. It is more common in young adults between 20 and 40 years of age. It is more common in females with the rate of growth enhanced in pregnancy. It occurs commonly in the distal femur, the proximal tibia, the distal radius and the sacrum. Giant cell tumors (GCT) usually prefers the epiphyses of long bones. The involvement of the metaphysis or diaphysis without epiphyseal extension is quite uncommon. Often the tumour extends to the articular subchondral bone, However it seldom crosses the joint or its capsule.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

- Patients usually present with pain and limited range of motion caused by tumor's proximity to the joint space.

- There may be swelling as well, if the tumor has been growing for a long time.

- Some patients may be asymptomatic until they develop a pathologic fracture at the site of the tumor.

X-Ray

MRI

MRI can be used to assess intramedullary and soft tissue extension.

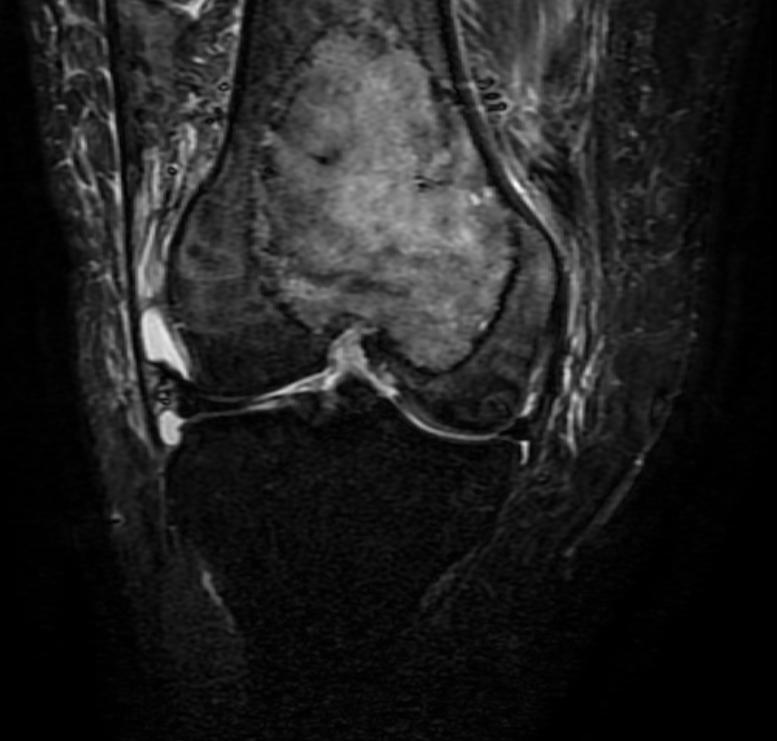

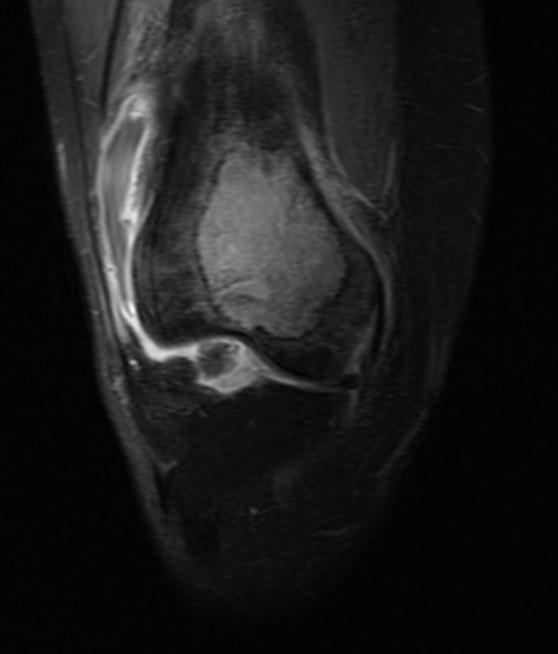

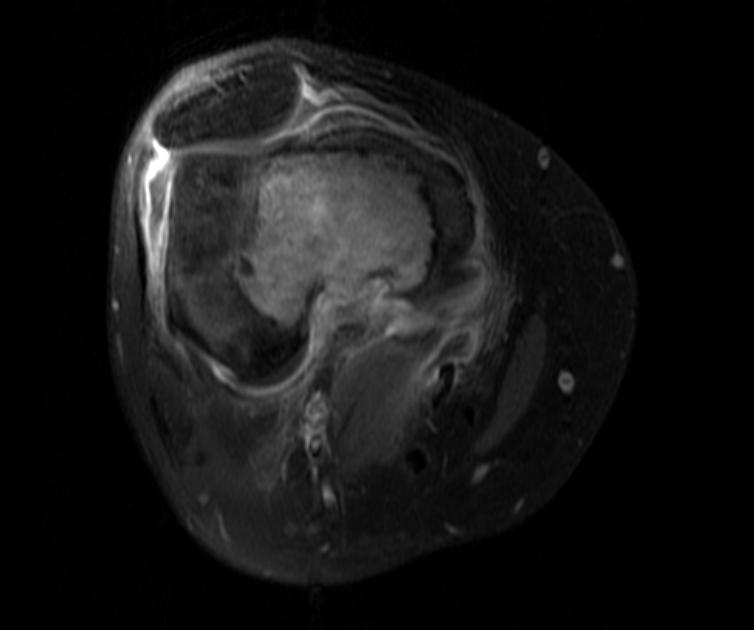

(Images courtesy of RadsWiki) Patient #1

-

Giant cell tumor: Distal part of the femur

-

Giant cell tumor: Distal part of the femur

-

Giant cell tumor: Distal part of the femur

Radiation Therapy

Patients with tumors that are not amenable to surgery are treated with radiation therapy [3].

Surgery

The treatment of choice is intralesional curettage and bone cement packing leading to a local recurrence rate of 10 to 40%. Treatment options are limited and recurrence rates are higher when GCT arises at a surgical inaccessible location (e.g. spine and sacrum). In addition, some GCT may rarely arise at multiple sites or undergo sarcomatous transformation. In about 2% of cases, patients develop lung metastases, which are thought to represent benign pulmonary implants that arise following vascular invasion.[4]

- Surgery is the treatment of choice if the tumor is determined to be resectable.

- The situation is complicated in a patient with a pathological fracture. It may be best to immobilize the affected limb and wait for the fracture to heal before performing surgery.

References

- ↑ Gamberi G, Serra M, Ragazzini P, Magagnoli G, Pazzaglia L, Ponticelli F, Ferrari C, Zanasi M, Bertoni F, Picci P, Benassi MS (2003). "Identification of markers of possible prognostic value in 57 giant cell tumors of bone". Oncology Reports. 10 (2): 351–6. PMID 12579271. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

- ↑ Shrivastava, Sandeep; Nawghare, Shishir P; Kolwadkar, Yogesh; Singh, Pradeep (2008). "Giant cell tumour in the diaphysis of radius – a report". Cases Journal. 1 (1): 106. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-1-106. ISSN 1757-1626.

- ↑ Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP, Mendenhall NP (2006). "Giant cell tumor of bone". American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (1): 96–9. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000195089.11620.b7. PMID 16462511. Retrieved 2012-01-18. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Balke, Maurice; Neumann, Anna; Szuhai, Károly; Agelopoulos, Konstantin; August, Christian; Gosheger, Georg; Hogendoorn, Pancras CW; Athanasou, Nick; Buerger, Horst; Hagedorn, Martin (2011). "A short-term in vivo model for giant cell tumor of bone". BMC Cancer. 11 (1): 241. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-11-241. ISSN 1471-2407.